East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:148-55

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Jilan Rameshchandra Mehta, MBBS, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Dr Imran Jahangirali Ratnani, MBBS, Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Dr Jigna Dinkarbhai Dave, MD, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Dr Bharat Navinchandra Panchal, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Dr Amit Khimjibhai Patel, MD, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Dr Ashok Ukabhai Vala, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr Imran Jahangirali Ratnani, Room No. 133, Department of Psychiatry, Government Medical College and Sir Takhtasinhji General Hospital, Bhavnagar, Gujarat, India.

Tel: (91) 9925056695; Fax: (91-278) 2422011; Email: drijratnani@gmail.com

Submitted: 7 March 2014; Accepted: 12 May 2014

Objective: This was a single-centre, cross-sectional, observational study performed at a tertiary care hospital in India to study the association of psychiatric co-morbidities and quality of life with severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods: A total of 59 clinically stable patients with COPD were assessed for disease severity, as per the updated Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guideline (2013). Psychiatric co-morbidities like anxiety disorders and depression were diagnosed by clinician-administered interview (as per the DSM-V criteria). Insomnia, anxiety disorders and depression, as well as quality of life were also assessed by self-rating scales including Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, respectively.

Results: Depression was the commonest psychiatric co-morbidity affecting 32.2% of individuals. Patients with depression and anxiety disorders had higher score in COPD assessment test (p = 0.02 and p = 0.004, respectively), ISI (p < 0.001 and p = 0.01, respectively), and poorer quality of life (p < 0.001 and p = 0.02, respectively) compared with those without these conditions. Patients with severe symptoms of COPD were more likely to suffer from anxiety (p = 0.001), depression (p = 0.01), insomnia (p = 0.01), and have poor quality of life (p < 0.001). Patients in the GOLD-D (i.e. those at high risk and with more symptoms) group had poorer quality of life (p = 0.004) when compared with GOLD-A (low risk and less symptoms) and GOLD-C (high risk and less symptoms) groups.

Conclusions: Patients with psychiatric co-morbidities have severe symptoms of COPD and poor quality of life.

Key words: Anxiety; Depression; Mental disorders; Pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive; Quality of life

目的:這項單中心橫斷面觀察性研究於印度一所第三層醫療服務醫院進行,旨在檢視精神病共病和生活質量跟慢性阻塞性肺病重度的相關性。

方法:根據2013年「慢性阻塞性肺病全球倡議組織」(GOLD)指引,納入59名慢性阻塞性肺病病情穩定的患者進行疾病重度評估。研究透過臨床管理訪談(基於DSM-V診斷標準)診斷包括焦慮和抑鬱等精神科共病,並以自評量表包括失眠重度指數(ISI)、醫院焦慮抑鬱量表,以及聖喬治呼吸問卷分別對患者的失眠、焦慮抑鬱,以及生活質量作出評估。

結果:抑鬱是最常見的精神病共病,佔患者總數32.2%。患者如出現抑鬱和焦慮症狀,其慢性阻塞性肺病評估測試得分(p = 0.02和p = 0.004)和ISI得分(p < 0.001和p = 0.01)都明顯較沒有這些症狀的患者為高,生活質量也較差(p < 0.01和p = 0.02)。慢性阻塞性肺病嚴重的患者較容易出現焦慮(p = 0.001)、抑鬱(p = 0.01)、失眠(p = 0.01),以及較差的生活質量(p < 0.001)。與GOLD-A組(低風險少症狀患者)和GOLD-C組(高風險少症狀患者)比較,GOLD-D組(高風險多症狀患者)的生活質量較差(p = 0.004)。結論:精神病共病患者的慢性阻塞性肺病較為嚴重,生活質量也較差。

關鍵詞:焦慮症、抑鬱症、精神障礙、肺病,慢性阻塞性、生活質量

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a preventable and treatable respiratory disease characterised by irreversibility of airflow limitations and dyspnoea, affecting the individual’s physical health and quality of life, which are the leading causes of disability and death.1,2 Psychiatric illnesses are increasingly common in patients with chronic illnesses; despite this, psychiatric co-morbidities among patients with COPD are less studied in comparison with general medical conditions.1 Psychiatric co-morbidities contribute significantly to functional impairment in patients with COPD, and treatment of these serves to improve both the psychiatric and pulmonary status.1,3 Anxiety disorders and depression are the commonest psychiatry diagnoses among the COPD patients.4 Prevalence of anxiety disorders varies from 2% to > 50% in various studies, while that of depression varies from 6% to 42%.5-7 Higher frequency of anxiety disorders and depression is correlated with severity of COPD.6,7 Earlier, the severity of COPD was classified based on FEV1 value (i.e. % of predicted value of forced expiratory volume in one second) into various stages of Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).2,6,8 Updated GOLD guideline (2013)2 recommended additional inclusion of current level of symptoms, exacerbation risk, and presence of co-morbidity in the classification of severity, as there were weak correlations with FEV1, symptoms, and impairment in health-related quality of life.

As there is no published evidence assessing psychiatric co-morbidities and quality of life with severity of COPD classified by the updated GOLD guideline, we evaluated association of psychiatric co-morbidities (including insomnia, anxiety disorders, depression, obsessive- compulsive disorder) and quality of life with severity of COPD classified according to the updated GOLD guideline.

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between September and November 2013 and recruited 59 consecutive patients attending the outpatient clinic of the department of pulmonary medicine at a tertiary care hospital in India. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the ethics committee. Patients of both genders, who gave consent and were diagnosed with COPD according to updated GOLD guideline, were included in the study. Data collected included demographic details, history of smoking, tobacco chewing, as well as a history and family history of psychiatric illness. Patients with acute respiratory exacerbation, chronic disabling conditions, inability to give verbal reply, acute or chronic confusion state, or psychotic disorders were excluded. Severity of COPD was classified as per recommendations of the updated GOLD guideline, including spirometry parameters, severity of symptoms (assessed by modified British Medical Research Council [mMRC] questionnaire and COPD assessment test [CAT]), and risk of exacerbations.2 The CAT is an 8-item questionnaire for assessing and quantifying the impact of COPD symptoms on health status.2 The questionnaires that the participants were asked to complete included performa- containing Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) for the assessment of insomnia, anxiety and depression status, and quality of life, respectively.9-11 Insomnia Severity Index is a 7-item Likert scale for screening and assessing severity of sleep disturbance.9 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a validated screening tool for detection of anxiety disorders and depression in patients with chronic illnesses10; it constitutes 7 items for anxiety disorders and 7 items for depression to be rated on a 4-point (0 to 3) Likert scale.10 St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire is a 50-item scale widely used for assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with respiratory disease in the domains of symptoms (distress due to symptoms), activities (effect due to impairment in physical activity), and effect (psychological effect).11

Every participant was interviewed for the assessment of psychiatric co-morbidities like anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder as per the DSM-V criteria.12 The psychiatry diagnosis was confirmed by a consultant psychiatrist.

Qualitative data were expressed as proportions and quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis was done with GraphPad InStat version 3.06. Proportions were compared by using Chi-square test while scores of FEV1, mMRC, CAT, ISI, HADS, and SGRQ were compared using Mann-Whitney test or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test multiple comparisons. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

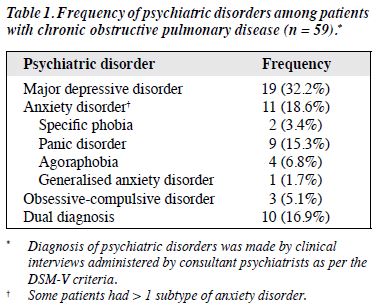

Overall, 59 consecutive patients with COPD of varying severity were assessed for their psychiatric co-morbidities and quality of life. As shown in Table 1, major depressive disorder was the commonest psychiatric co-morbidity affecting about 32.2% of patients with COPD, followed by anxiety disorders (18.6%). Panic disorder (15.3%) was the most frequent anxiety disorder.

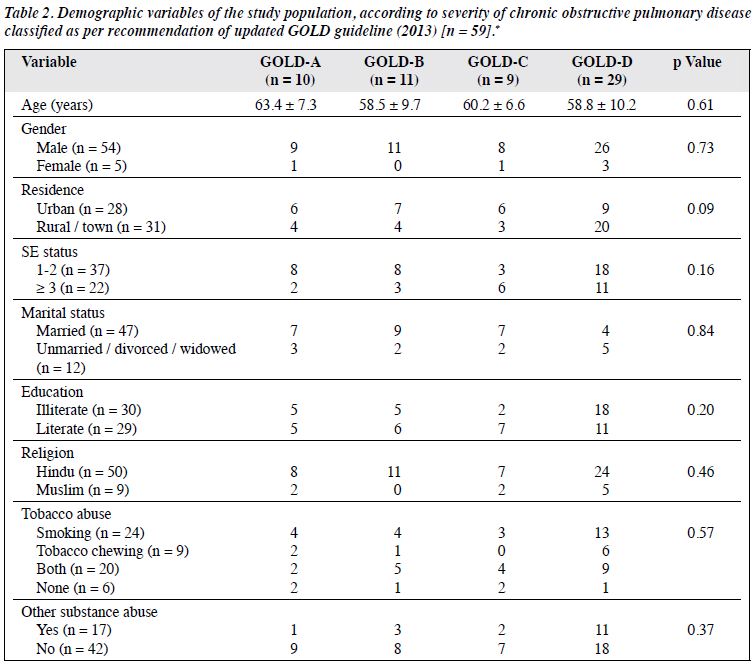

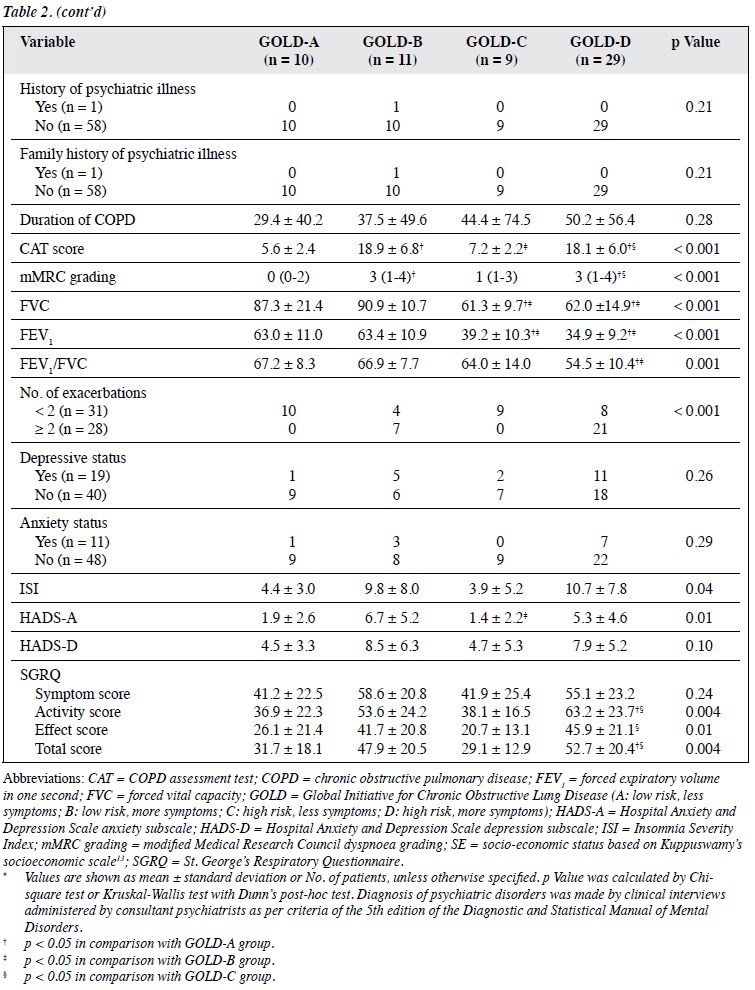

Demographic variables of the study population are presented in Table 2.13 Patients were classified based on the severity of COPD as per the recommendation of revised GOLD guideline. Patients from GOLD-D group (high risk, more symptoms) were likely to have poorer disease- related quality of life (high SGRQ score) than those from GOLD-A (low risk, less symptoms) and GOLD-C groups (high risk, less symptoms). Patients in GOLD-B group (low risk, more symptoms) were likely to have higher HADS anxiety subscale score compared with those in the GOLD-C group.

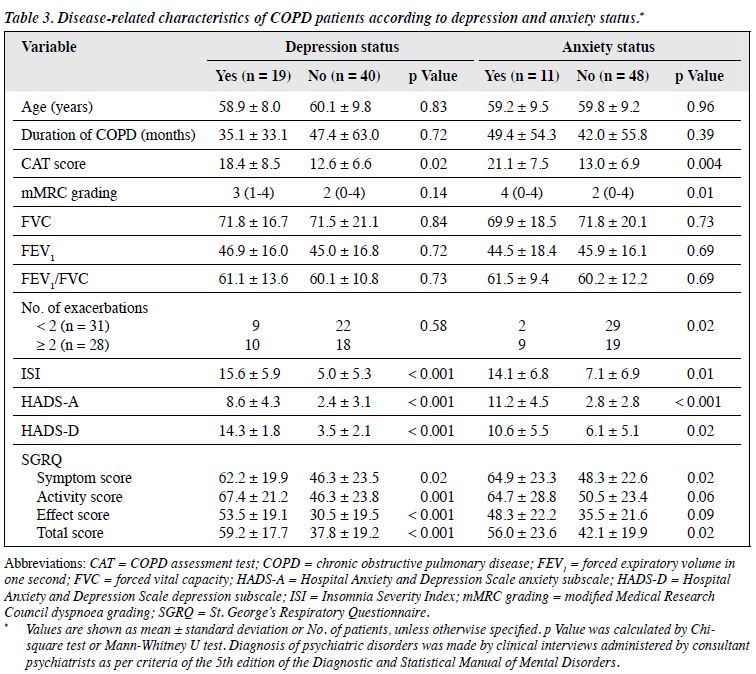

Table 3 shows disease-related characteristics of COPD patients based on their anxiety and depression status. Patients with depression and anxiety disorders were likely to have higher CAT score (p = 0.02 and p = 0.004, respectively), higher ISI (p < 0.001 and p = 0.01, respectively), and poorer quality of life represented by higher SGRQ score (p < 0.001 and p = 0.02, respectively) compared with those without these conditions.

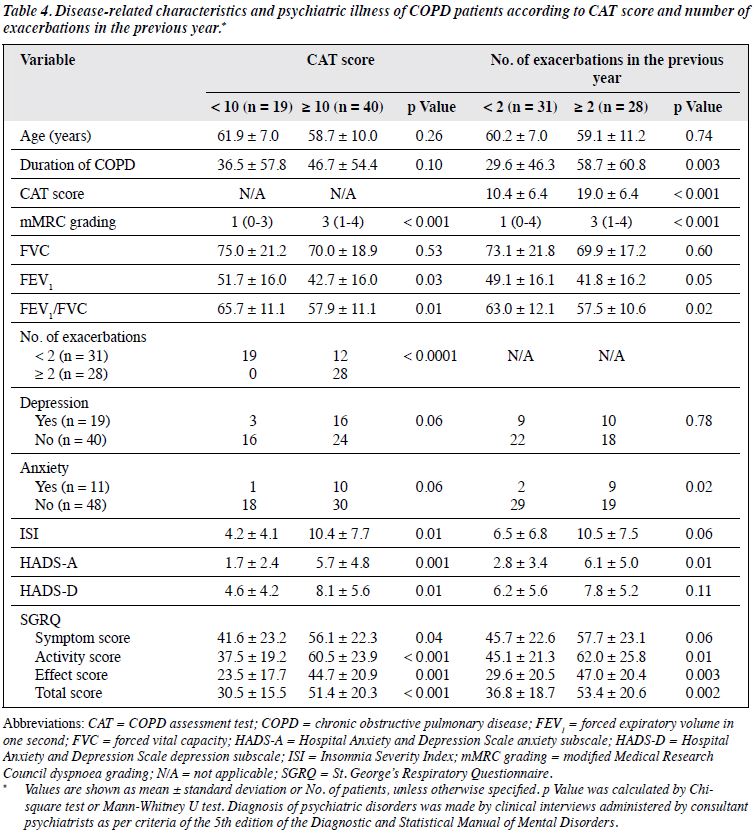

As shown in Table 4, patients with severe COPD symptoms (i.e. CAT score ≥ 10) were more likely to have severe breathlessness (higher mMRC score, p < 0.001) and more (i.e. ≥ 2) exacerbations in the previous year (p < 0.001). Furthermore, they were more likely to suffer from insomnia (p = 0.01), anxiety (p = 0.001), depression (p = 0.01), and had poorer quality of life (p < 0.001). Patients with ≥ 2 exacerbations in the previous year had longer duration of COPD (p = 0.003), higher CAT score (p < 0.001), dyspnoea (mMRC) grading (p < 0.001), anxiety score (p = 0.01), and poor quality of life (p = 0.002).

Psychiatric illnesses like anxiety disorders and depression are more frequent among patients with chronic medical illnesses like COPD in comparison with the general population.1

The majority of the study population were males (92%). This is consistent with studies showing that males are 25 times more likely to smoke than females in developing countries like India, and smoking is the most widely studied risk factor for the development of COPD.2,14 Almost all reported Indian studies state that COPD is more prevalent among males with a median male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1.15 These could be the probable reasons for gender difference. Overall, 90% of our study population was using tobacco, and more than three quarters were smokers. These findings are in accordance with those from an earlier study which showed that the prevalence of COPD was higher among males in comparison to females and smokers are more likely to develop COPD when compared with non-smokers.16

Nearly half of the study population belonged to the GOLD-D group which represented patients with high risk and more symptoms.2 As participants were recruited from the pulmonary medicine department of a tertiary care hospital (which is the highest referral centre in the locality for respiratory illnesses), patients with severe disease were more likely to use health care system disproportionately. This could be the probable reason for clustering of patients in this group.

We found major depressive disorder to be the commonest psychiatric co-morbidity associated with COPD, affecting 32.2% of the patients with COPD. Prevalence of depression varied from 6% to 42% in various studies.5-7 A hospital-based study in Denmark17,18 reported the frequency of depression as 47% (33% prevalence of major depressive disorder and 14% prevalence of mild depression). Our findings are very close to these data.

In accordance with an earlier study,19 we found that patients with depression and anxiety disorders had severe respiratory symptoms (i.e. high CAT score). The study19 also recommended screening for depression in subjects with CAT score of ≥ 21. This aligns with the finding in our study where the mean CAT score among depressed individuals was 18.4 ± 8.5.

There was an increased frequency of exacerbation in the previous year among patients with higher CAT score. Similar finding was observed in an earlier study.20 In accordance with findings from the same study,20 patients with severe respiratory symptoms had severe dyspnoea (i.e. higher mMRC grading).

Prevalence of anxiety disorder varies from 2% to 50% in published studies.5,6,17 Frequency of anxiety disorder was 18.6% in our study, similar to that in an earlier study.21 In consistency with majority of studies, panic disorder was the commonest anxiety diagnosis.22 Anxiety and dyspnoea are important for the health status of patients with COPD. Consistent with previous findings,23 patients with anxiety disorders had higher grades of dyspnoea and more exacerbations in the previous year. Patients with ≥ 2 exacerbations in the previous year were likely to have longer duration of illness, consistent with data from a previous study24 that patients with longer duration of illness had increased chances of more (i.e. ≥ 2) exacerbations.24

Insomnia is 3 times more prevalent among patients with COPD in comparison with the general population.25 In contrast to findings from an earlier study that the prevalence of insomnia was not significantly different in different GOLD stages of COPD,25 severity of insomnia was correlated with severity of COPD in the present study, probably because of change in severity classification by incorporating severity of symptoms and number of exacerbations in the previous year, according to the updated GOLD guideline.2 Co-morbid depression and anxiety disorders were also significantly associated with insomnia.

There were discrepancies in results from previous studies for correlation of COPD severity with functional status of the individual.1,2,6,7 We found significant association between quality of life and severity of COPD, especially activity and effect domains of SGRQ. Inclusion of severity of symptoms in the severity classification of updated GOLD guideline could have contributed to this finding. Depression, anxiety disorders, severe respiratory symptoms (CAT score ≥ 10), and ≥ 2 exacerbations in the previous year were associated with poorer quality of life. Similar findings were reported in earlier studies.20,26

Psychiatric co-morbidity and quality of life among patients with COPD, classified according to the updated GOLD guideline, have not been evaluated earlier. The diagnosis of psychiatric illnesses was made by clinician- administered interviews as per the DSM-V criteria. In spite of the above strength, our study has several limitations such as recruiting clinically stable COPD patients and excluding patients with acute exacerbations. Sample size was small and all the participants were recruited from a single tertiary care hospital. Being a cross-sectional study, cause-effect relationship could not be established with this study. We recommend further population-based, multicentre cohort studies for establishing the same.

In conclusion, depression is the commonest psychiatric co-morbidity in COPD patients. Patients with depression and anxiety disorders have increased chances of severe respiratory symptoms, higher frequency of insomnia, and poorer quality of life. Patients with severe respiratory symptoms are more likely to suffer from insomnia, anxiety disorders and depression, and have poorer quality of life.

The authors declared no conflict of interests in this study.

- Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, Hillman SL, Lalani S, Orengo CA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients: the impact of anxiety and depression. Psychosomatics 2000;41:465-71.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Website: http://www.goldcopd.org. Accessed 5 Jan 2014.

- Burns BH, Howell JB. Disproportionately severe breathlessness in chronic bronchitis. Q J Med 1969;38:277-94.

- Kunik ME, Roundy K, Veazey C, Souchek J, Richardson P, Wray NP, et al. Surprisingly high prevalence of anxiety and depression in chronic breathing disorders. Chest 2005;127:1205-11.

- Light RW, Merrill EJ, Despars JA, Gordon GH, Mutalipassi LR. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with COPD. Relationship to functional capacity. Chest 1985;87:35-8.

- Dowson C, Laing R, Barraclough R, Town I, Mulder R, Norris K, et al. The use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pilot study. N Z Med J 2001;114:447-9.

- van Ede L, Yzermans CJ, Brouwer HJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Thorax 1999;54:688-92.

- Lou P, Zhu Y, Chen P, Zhang P, Yu J, Zhang N, et al. Prevalence and correlations with depression, anxiety, and other features in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a cross-sectional case control study. BMC Pulm Med 2012;12:53.

- Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70.

- 1 Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Respir Med 1991;85 Suppl B:25-31.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Kumar N, Gupta N, Kishore J. Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale: updating income ranges for the year 2012. Indian J Public Health 2012;56:103-4.

- Neufeld KJ, Peters DH, Rani M, Bonu S, Brooner RK. Regular use of alcohol and tobacco in India and its association with age, gender, and poverty. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;77:283-91.

- Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. A review of population studies from India to estimate national burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its association with smoking. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2001;43:139-47.

- Xu F, Yin X, Zhang M, Shen H, Lu L, Xu Y. Prevalence of physician- diagnosed COPD and its association with smoking among urban and rural residents in regional mainland China. Chest 2005;128:2818-23.

- Stage KB, Middelboe T, Pisinger C. Measurement of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Nord J Psychiatry 2003;57:297-301.

- Mikkelsen RL, Middelboe T, Pisinger C, Stage KB. Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A review. Nord J Psychiatry 2004;58:65-70.

- Lee YS, Park S, Oh YM, Lee SD, Park SW, Kim YS, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test can predict depression: a prospective multi-center study. J Korean Med Sci 2013;28:1048-54.

- Okutan O, Tas D, Demirer E, Kartaloglu Z. Evaluation of quality of life with the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment test in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the effect of dyspnea on disease-specific quality of life in these patients. Yonsei Med J 2013;54:1214-9.

- Karajgi B, Rifkin A, Doddi S, Kolli R. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:200-1.

- Willgoss TG, Yohannes AM. Anxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Respir Care 2013;58:858-66.

- Hajiro T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Ikeda A, Oga T. Stages of disease severity and factors that affect the health status of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2000;94:841-6.

- Cukic V, Lovre V, Ustamujic A. The changes of pulmonary function in COPD during four-year period. Mater Sociomed 2013;25:88-92.

- Budhiraja R, Parthasarathy S, Budhiraja P, Habib MP, Wendel C, Quan

- SF. Insomnia in patients with Sleep 2012;35:369-75.

- Di Marco F, Verga M, Reggente M, Maria Casanova F, Santus P, Blasi F, et al. Anxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severity. Respir Med 2006;100:1767-74.