East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2022;32:67-81 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2213

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Encarnita R Ampil, Department of Neuroscience and Behavioral Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Marisse D Dizon, Department of Neuroscience and Behavioral Medicine, University of Santo Tomas Hospital, Manila, Philippines

John Aldwin U Co, Department of Neuroscience and Behavioral Medicine, University of Santo Tomas Hospital, Manila, Philippines

Paulus Anam Ong, Department of Neurology, Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

Febby Rosa Annisafitrie, Department of Neurology, Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

Lucky Saputra, Department of Psychiatry, Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia

Sun-Wung Hsieh, Department of Neurology, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Yuan-Han Yang, Department of Neurology, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Address for correspondence: Encarnita R Ampil, Department of Neuroscience and Behavioral Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines.

Email: erampil@ust.edu.ph

Submitted: 23 February 2022; Accepted: 20 October 2022

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to determine factors associated with hesitation and motivation to work among healthcare workers (HCWs) in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: HCWs aged ≥20 years working in five hospitals in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan were invited to participate in a self-administered mental health survey between 30 January 2021 and 31 August 2021. The 33-item questionnaire measured HCWs’ perceived stress, level of motivation and hesitation to work, attitude and confidence regarding work, attitude on the policies by the hospital and government, and discrimination against the occupation. Each item was rated in a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Sociodemographic and occupational factors were also considered in data analysis.

Results: Of 1349 participants, 671 (49.7%) were from Indonesia, 365 (27.1%) from Philippines, and 313 (23.2%) from Taiwan. Overall, 20.8% of participants showed motivation to work and only 4.7% showed hesitation to work. Compared with HCWs in their 20s, HCWs in their 30s, 40s, and 50s had significantly lower hesitation to work (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.42, 0.33, and 0.11, respectively; p = 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03, respectively). Similarly, compared with HCWs in their 20s, HCWs in their 30, 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s had significantly higher motivation to work (AOR = 1.71, 2.98, 5.92, 5.40, and 7.15, respectively; p = 0.01, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, and 0.02, respectively). Clinical staff had lower motivation to work than non-clinical staff (AOR = 0.60, p = 0.01). Those who worked in high-risk areas had lower hesitation to work than those who worked in low-risk areas (AOR = 0.51, p = 0.03). Overall, higher hesitation to work was associated with ‘wanting to leave job/study’ (AOR = 4.54, p = 0.03) and ‘feeling isolated’ (AOR = 4.84, p = 0.01), whereas lower hesitation to work was associated with ‘being confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 0.33, p = 0.02) and ‘burden of child care including lack of nursery’ (AOR = 0.30, p = 0.04). Higher motivation to work was associated with ‘feeling of being protected by hospital’ (AOR = 2.23, p = 0.001), ‘confident in my country’s pandemic prevention policy’ (AOR = 2.19, p = 0.001), ‘feeling of elevated mood’ (AOR = 4.14, p = 0.004), and ‘being confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 2.56, p < 0.001), whereas lower motivation to work was associated with ‘exhausted mentally’ (AOR = 0.35, p = 0.03).

Conclusion: Various stress-related factors contribute to hesitation and motivation to work among HCWs in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proactive and practical strategies should be implemented to protect HCWs from the negative behavioural and emotional effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key words: COVID-19; Health personnel; Mental health; Motivation; Surveys and questionnaires

Introduction

The extent of mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people varies, depending on personal factors, economic changes, and healthcare policies. Among seven middle-income Asian countries during the pandemic, the rates of depression and anxiety and levels of stress were highest in Thailand and lowest in Vietnam.1 The differences may be due to the economic impact of the pandemic rather than the number of infections. In a study comparing the Philippines (a lower-middle-income country) with China (an upper-middle-income country), the mental health impact of the pandemic on the general public was significantly higher in the former than in the latter.2 Inadequate health education and testing for COVID in the former may have contributed to this finding.

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at a greater risk of having mental health problems, particularly during the outbreak of infectious diseases.3,4 HCWs are in direct or indirect contact with patients and thus are at a higher risk of infection, which may cause psychological stress and may compromise patient care. This study aims to determine factors associated with hesitation and motivation to work among HCWs in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of all participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. Between 30 January 2021 and 31 August 2021, HCWs aged >20 years working in five hospitals (Hasan Sadikin Hospital in Indonesia, University of Santo Tomas Hospital in Philippines, and Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Hsiao-Kang Hospital, and Ta-tung Hospital in Taiwan) were invited to participate in a self-administered mental health survey through papers or Google Form. The five hospitals admitted patients with COVID-19 infection, except for Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital.

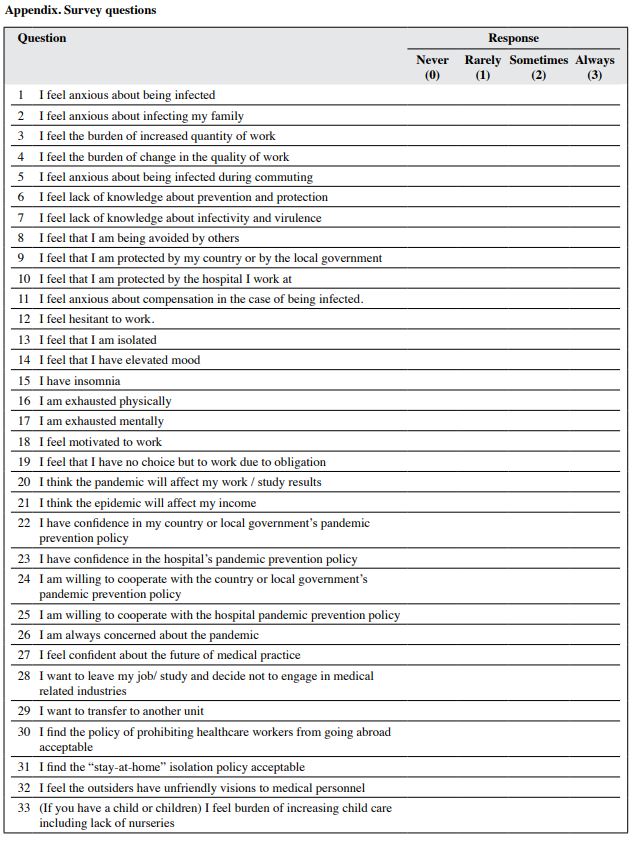

The mental health survey was derived from the survey on hospital workers during the H1N1 pandemic in 2009,5 which evaluated hospital workers’ willingness to work and its associated factors. Willingness to work is a personal decision different from the capacity of an individual to work.6 The original 20-item questionnaire (items 1-19 and 33) measures hospital workers’ perceived stress and motivation and hesitation to work during the H1N1 pandemic. In our survey, 13 questions (items 20-32) were added to evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on participants’ attitude and confidence regarding work and policies by the hospital and government, and their attitude on discrimination against the occupation (Appendix). Each item was rated in a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always).

Attitudes or perceptions of the HCWs were categorised into: (1) being infected or infecting others, (2) having adequate knowledge about COVID-19, (3) being protected by the government or hospital or receiving compensation if infected, (4) confidence in prevention policies and willingness to follow these policies, (5) work condition being affected by the pandemic, (6) government policies on isolation and prohibition of HCWs from going abroad, (7) hesitation and motivation to work, (8) discrimination by others, and (9) having specific symptoms related to mood and anxiety. Responses to the stress-related questions and motivation and hesitation to work were dichotomised to weak (score of ≤2) and strong (score of 3). Multivariate logistic regression models were adjusted for age, sex, clinical staff, risk of exposure at work, and stress- related factors. Associations of participant characteristics and stress-related questions with motivation and hesitation to work were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence interval. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.

Results

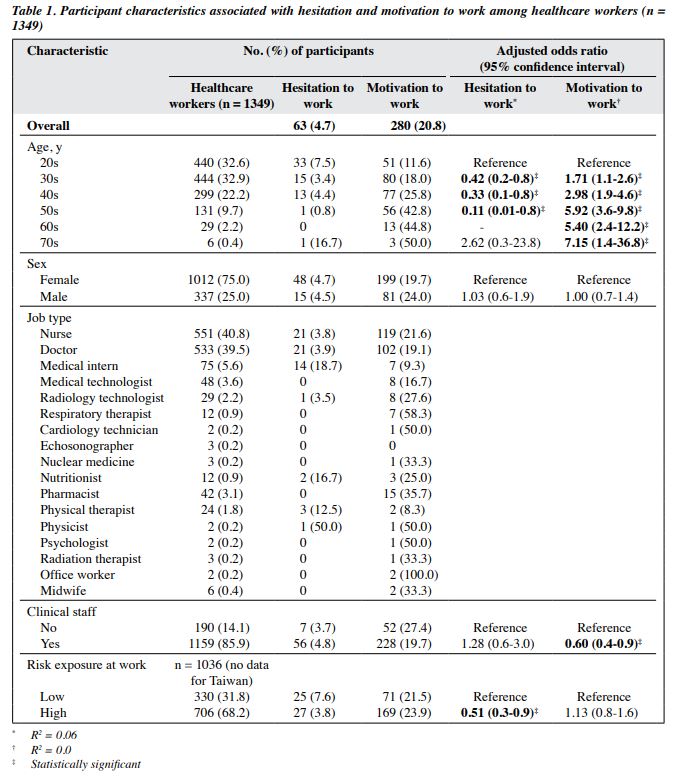

Of 1349 participants, 671 (49.7%) were from Indonesia, 365 (27.1%) from Philippines, and 313 (23.2%) from Taiwan (Table 1). 75% of participants were women. 32.9% of participants were in their 30s, 32.6% in their 20s, and the remaining in their 40s to 70s. 85.9% of participants were clinical staff (nurses and doctors) and the remaining 14.1% were non-clinical staff with less patient interaction. 68.2% of the clinical staff worked in high-risk areas (such as COVID-19 wards) and the remaining 31.8% worked in low-risk areas.

Overall, 20.8% of participants showed motivation to work and only 4.7% showed hesitation to work. Compared with HCWs in their 20s, HCWs in their 30s, 40s, and 50s had significantly lower hesitation to work (AOR = 0.42, 0.33, and 0.11, respectively; p = 0.01, 0.02, and 0.03, respectively) [Table 1]. Similarly, compared with HCWs in their 20s, HCWs in their 30, 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s had significantly higher motivation to work (AOR = 1.71, 2.98, 5.92, 5.40, and 7.15, respectively; p = 0.01, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, and 0.02, respectively). Clinical staff had lower motivation to work than non-clinical staff (AOR = 0.60, p = 0.01), with no significant difference in hesitation to work. Those who worked in high-risk areas had lower hesitation to work than those who worked in low-risk areas (AOR = 0.51, p = 0.03), with no significant difference in motivation to work.

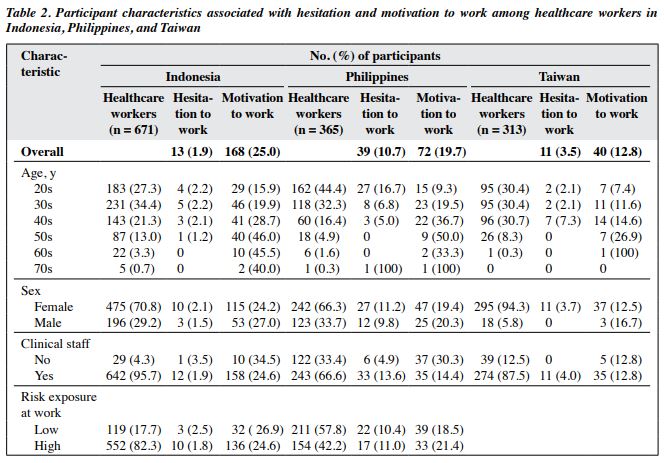

Table 2 shows the characteristics of HCWs in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan and their associations with hesitation and motivation to work. In Indonesia, HCWs in their 30s, 40s, and 50s had higher motivation to work than those in their 20s (AOR = 2.11, 4.45, 4.38, respectively; p = 0.007, <0.001, and 0.002, respectively), with no significant difference in hesitation to work. In the Philippines, HCWs in their 30s had lower hesitation to work (AOR = 0.34, p = 0.01) and higher motivation to work (AOR = 2.49, p = 0.01) than those in their 20s. Similarly, HCWs in their 40s and 50s had higher motivation to work than those in their 20s (AOR = 4.75 and 7.78, respectively, both p < 0.001). Clinical staff had lower motivation to work than non-clinical staff (AOR = 0.48, p = 0.01), with no significant difference in hesitation to work. In Taiwan, HCWs in their 50s had higher motivation to work than those in their 20s (AOR = 4.85, p = 0.009), with no significant difference in hesitation to work.

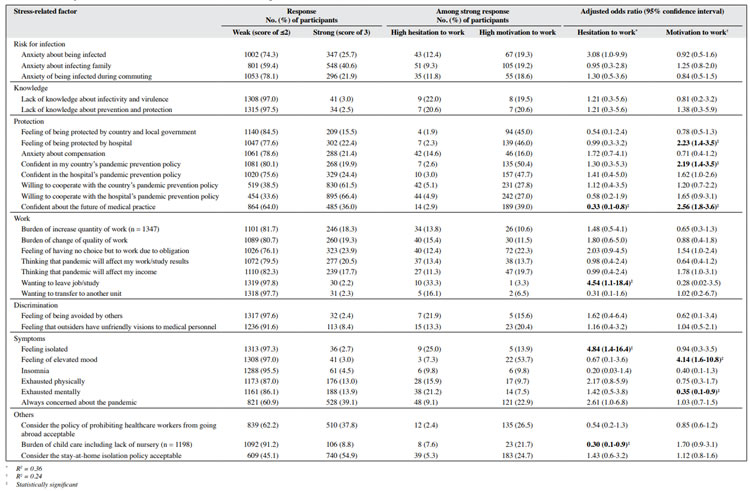

Table 3 shows associations of stress-related factors of HCWs with hesitation and motivation to work. Overall, higher hesitation to work was associated with ‘wanting to leave job/study’ (AOR = 4.54, p = 0.03) and ‘feeling isolated’ (AOR = 4.84, p = 0.01), whereas lower hesitation to work was associated with ‘being confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 0.33, p = 0.02) and ‘burden of child care including lack of nursery’ (AOR = 0.30, p = 0.04). Higher motivation to work was associated with ‘feeling of being protected by hospital’ (AOR = 2.23, p = 0.001), ‘confident in my country’s pandemic prevention policy’ (AOR = 2.19, p = 0.001), ‘feeling of elevated mood’ (AOR = 4.14, p = 0.004), and ‘being confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 2.56, p < 0.001), whereas lower motivation to work was associated with ‘exhausted mentally’ (AOR = 0.35, p = 0.03).

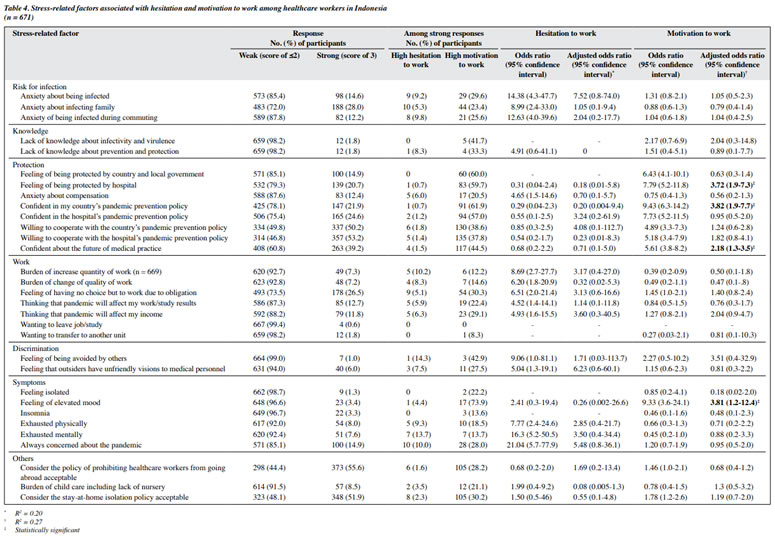

In Indonesia, hesitation to work was not associated with any stress-related factors of HCWs. Higher motivation to work was associated with ‘feeling of being protected by hospital’ (AOR = 3.72, p < 0.001), ‘confident in my country’s pandemic prevention policy’ (AOR = 3.82, p < 0.001), ‘confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 2.18, p = 0.002), and ‘feeling of elevated mood’ (AOR = 3.81, p = 0.03) [Table 4].

In the Philippines, higher hesitation to work was associated with ‘anxiety of being infected during commuting’ (AOR = 25.6, p = 0.02). Two other stress- related factors of HCWs—‘wanting to leave job/study’ (AOR = 3.11e+12, p = 0.99) and ‘feeling of being avoided by others’ (AOR = 7.53e-12, p = 0.99)—had very high AOR and wide confidence interval / variability in responses but were not statistically significant. Lower hesitation to work was associated with ‘confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 0.03, p = 0.02). Higher motivation to work was associated with ‘confident in the hospital’s pandemic prevention policy’ (AOR = 11.81, p = 0.01) and ‘feeling that outsiders have unfriendly visions to medical personnel’ (AOR = 20.22, p = 0.03) [Table 5].

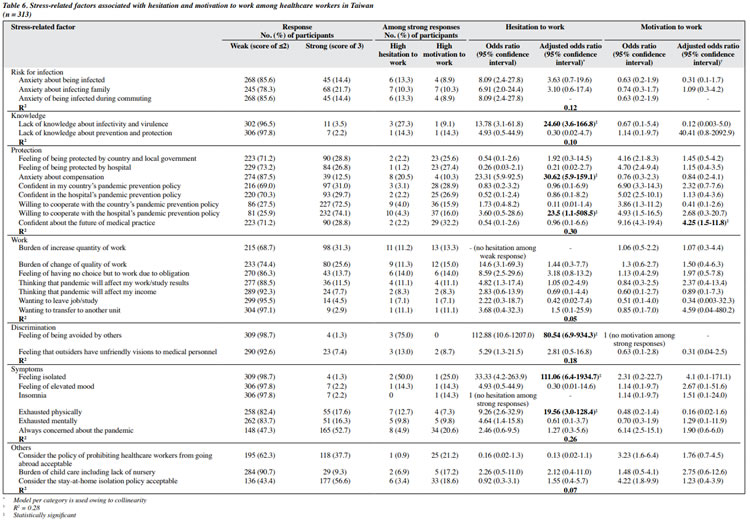

In Taiwan, higher hesitation to work was associated with ‘lack of knowledge about infectiousness and virulence’ (AOR = 24.60, p = 0.001), ‘anxiety about compensation’ (AOR = 30.62, p < 0.001), ‘willing to cooperate with the hospital’s pandemic prevention policy’ (AOR = 23.5, p = 0.04), ‘feeling of being avoided by others’ (AOR = 80.54, p < 0.001), ‘feeling isolated’ (AOR = 111.06, p = 0.001), and ‘exhausted physically’ (AOR = 19.56, p = 0.002). Higher motivation to work was associated with ‘confident about the future of medical practice’ (AOR = 4.25, p = 0.01) [Table 6].

Discussion

During a state of emergency, motivation and hesitation to work of HCWs affect the rate of absenteeism. Higher motivation and lower hesitation to work promotes healthy and balanced mental health of HCWs in the hospital.7

However, higher motivation may cause subsequent burnout, and higher hesitation may cause impediment to work in a high-risk situation.5

During the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs in their 30s to 50s showed higher motivation and lower hesitation to work. Younger HCWs may be more apprehensive about the effects of the pandemic and its consequences.8 Young HCWs are among the most junior workforce and may have future expectations about their careers.7 Clinical staff involved with direct care of patients (physicians and nurses) showed lower motivation to work than support/technical staff because of longer exposure in the wards. Incentive should be provided to clinical staff involved with patient care to increase their motivation to work.5

‘Confidence in the future of medical practice’ was an important factor associated with higher motivation to work among HCWs in Indonesia and Taiwan and lower hesitation to work among HCWs in the Philippines. This may be due to the worldwide efforts against COVID-19. Development of vaccines during the first quarter of 2021 may have strongly affected the response,9-11 as HCWs were the first recipients of the vaccines. The early roll out and approval of the vaccines for emergency use increase the confidence of the HCWs.12 Scientific reports and centres that enable better diagnosis and management of COVID-19 may have increased the confidence of HCWs in the future of medical practice.

Most HCWs showed willingness to follow hospital and government policies on prevention measures; the feeling of being protected by the hospital and the government increased motivation to work, particularly in Indonesia and the Philippines, where there are strict implementation of mask wearing in public places, social distancing, handwashing, and vaccination. In Indonesia, despite some delay in response to the surge during the second quarter of 2021, the government implemented restrictions towards community activities.13 In the Philippines, the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases14 coordinated efforts of local and national governments against the COVID-19 pandemic. In Taiwan, the government immediately activated the Central Epidemic Command Center under the National Health Command Center15,16 to oversee quarantine, contact tracing, and surveillance of COVID-19.

In the Philippines, ‘wanting to leave job/study’resulted in higher hesitation to work. Most HCWs considered the policy of prohibiting HCWs from going abroad weakly acceptable. During the early phase of the pandemic, the government barred HCWs from leaving the country owing to the increasing infection cases and manpower shortage (secondary to absenteeism or illness).17,18 It was only in November 2020 that the government lifted this ban and placed a ceiling cap for overseas deployment.19 The feeling of being isolated increased hesitation to work, as most HCWs chose to live away / separately from their families for fear of infecting them. The perception of the general population against HCWs may add to the feeling of isolation.3 The general population tended to avoid contact with HCWs. In Taiwan, HCWs also had the feeling of isolation and being avoided by others.

Most HCWs were mentally exhausted. In Taiwan, HCWs also reported physical exhaustion. Hospitals should adjust work schedule to reduce overtime and the ratio of HCWs to patients and to increase the workforce in the high- risk areas.5,20 Granting leaves with proper compensation may help HCWs recuperate. Provision of psychological support/therapy and support groups may help HCWs to cope better during the pandemic.20,21

In the Philippines, ‘anxiety of being infected during commuting’ was associated with higher hesitation to work. During the beginning of the pandemic, a nationwide lockdown was imposed, and public transportation was prohibited from operating. Only some hospitals deployed free shuttles for HCWs, but none was available for HCWs included in our study. Strategies to overcome barriers in transportation should ensure those needing these services have access.22 In Taiwan, the lack of knowledge about infectivity and virulence resulted in higher hesitation to work. The government should disseminate safe health practices through education. However, disseminating this information to rural areas may be difficult because of different lifestyle practices and resources.16

There are conflicting results in the present study. Lower hesitation to work was associated with ‘burden of child care including lack of nursery’. In the Philippines, higher motivation to work was associated with ‘feeling that outsiders have unfriendly visions to medical personnel’. Factors that are derogatory to HCWs are expected to negatively affect willingness to work.23 Despite the adversity, HCWs may strive harder, which may lead to higher motivation and lower hesitation to work.

In Taiwan, the government was able to foresee difficulties to people during the pandemic and successfully implemented mitigating measures,16 but HCWs still showed hesitation to work owing to different factors. Thus, it is important to regularly evaluate the needs of HCWs.

There are limitations to the present study. Previous COVID-19 infection among HCWs and their history of quarantine and/or isolation were not recorded. These factors may cause higher anxiety and distress and may affect motivation and hesitation to work. Our survey was conducted during a surge in COVID-19 cases, which may affect HCWs’ mental well-being. The pre-pandemic mental health state of participants was not assessed and may have affected the results. Interviews should have been conducted to explore the reasons behind the conflicting results.

Conclusion

Various stress-related factors contribute to hesitation and motivation to work among HCWs in Indonesia, Philippines, and Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors may cause mental health problems and physical exhaustion if not properly addressed. Proactive and practical strategies should be implemented to protect HCWs from the negative behavioural and emotional effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by University of Santo Tomas Hospital Research Ethics Committee (reference: REC- 2020-05-074-MD), Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital Institutional Review Board (reference: KMUHIRB-E(1)-20200178), and Research Ethics Committee Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia (reference: 1193/UN6.KEP/EC/2020).

References

- Wang C, Tee M, Roy AE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: a study of seven middle income countries in Asia. PLoS One 2021;16:e0246824. Crossref

- Tee M, Wang C, Tee C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in lower and upper middle-income Asian countries: a comparison between the Philippines and China. Front Psychiatry 2021;11:568929. Crossref

- Khanal P, Devkota N, Dahal M, Paudel K, Joshi D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: a cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Global Health 2020;16:89. Crossref

- Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, Kim T, Park JK. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry 2018;87:123-7. Crossref

- Imai H, Matsuishi K, Ito A, et al. Factors associated with motivation and hesitation to work among health professionals during a public crisis: a cross sectional study of hospital workers in Japan during the pandemic (H1N1) 2009. BMC Public Health 2010;10:672. Crossref

- Qureshi K, Gershon RR, Sherman MF, et al. Health care workers’ ability and willingness to report to duty during catastrophic disasters. J Urban Health 2005;82:378-88. Crossref

- Imai H. Trust is a key factor in the willingness of health professionals to work during the COVID-19 outbreak: experience from the H1N1 pandemic in Japan 2009. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:329-30 Crossref

- Bellotti L, Zaniboni S, Balducci C, Grote G. Rapid review on COVID-19, work-related aspects, and age differences. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:5166. Crossref

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603-15. Crossref

- Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCOV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomized controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021;397:99-111. Crossref

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021;21:181-92. Crossref

- Barry M, Temsah MH, Alhuzaimi A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine confidence and hesitancy among health care workers: a cross- sectional survey from a MERS-CoV experienced nation. PLoS One 2021;16:e0244415. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Indonesia Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report. Available from: https://cdn.who. int/media/docs/default-source/searo/indonesia/covid19/external- situation-report-80_10-november-2021.pdf.

- Republic of the Philippines Department of Health COVID-19 Inter- Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases Resolutions. Available from: https://doh.gov.ph/COVID-19/ IATF-Resolutions. Accessed November 20, 2021.

- Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. Available from: https://www.cdc. gov.tw.

- Hsu CH, Lin HH, Wang CC, Jhang S. How to defend COVID-19 in Taiwan? Talk about people’s disease awareness, attitudes, behaviors and the impact of physical and mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:4694. Crossref

- Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med 2020;77:281-2Crossref

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Governing Board Resolution No 09 Series of 2020. Available from: https://www.poea. gov.ph/gbr/2020/GBR-09-2020.pdf.

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Governing Board Resolution No 17 Series of 2020. Available from: https://www.poea. gov.ph/gbr/2020/GBR-17-2020.pdf.

- Juvet TM, Corbaz-Kurth S, Roos P, et al. Adapting to the unexpected: problematic work situations and resilience strategies in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic’s first wave. Saf Sci 2021;139:105277. Crossref

- Tomlin J, Dalgleish-Warburton B, Lamph G. Psychosocial support for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2020;11:1960. Crossref

- Chen KL, Brozen M, Rollman JE, et al. How is the COVID-19 pandemic shaping transportation access to health care? Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 2021;10:100338. Crossref

- Muthuri RNDK, Senkubuge F, Hongoro C. Determinants of motivation among healthcare workers in the East African community between 2009-2019: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 2020;8:164. Crossref