East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:95-100 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1970

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Serena SW Ng, Community Rehabilitation Service Support Centre, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Tony KS Leung, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong

Peggie PK Ng, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong

Ricky KH Ng, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong

Asta TY Wong, Occupational Therapy Department, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong

Address for correspondence: Dr Serena SW Ng, Community Rehabilitation Service Support Centre, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong

Email: ngsws@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 15 January 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020

Abstract

Objective: To examine associations between severe mental illness (SMI), general health symptoms, mental wellbeing, and different activity levels in patients with SMI.

Method: Consecutive patients with SMI referred for occupational therapy were prospectively included. Their hours of activities per day during hospital stay were recorded as <1 hour, 1-3 hours, and >3 hours in three categories: basic self-care activities, interest-based activities, and role-specific activities. Patients were free to join or decline any activities. Patients’ somatic and mental health were measured at admission, discharge, and 1 month after discharge using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Chinese version of Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (C-SWEMWBS), and Chinese version of General Activity Motivation Measure (GAMM).

Results: 84 patients (35 men and 49 women) aged 16 to 63 years were assessed at the three timepoints. The mean length of hospital stay of current admission was 74.73 days. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (n=35), followed by depression (n=15), psychosis (n=14), bipolar affective disorder (n=10), others (n=8), and delusional disorder (n=2). The hours of activities per day was <1 hour in 32 (38.1%) patients, 1-3 hours in 34 (40%) patients, and >3 hours in 18 (21.2%) patients. Improvement in somatic and mental health was positively associated with hours of activities per day. Activities were associated with reduced psychiatric symptoms (measured by BPRS) at discharge (Z = 5.978, p < 0.01). Activities were associated with less somatic complaints (measured by PHQ-15) [χ2.= 23.478, p < 0.01], better sleep quality (measured by PSQI) [χ2 = 14.762, p < 0.01]. The BPRS score for psychiatric symptoms at discharge was inversely associated with C-SWEMWBS score for mental wellbeing (r = -0.233, p = 0.033) and C-GAMM score for activity motivation (r = -0.258, p = 0.018). Basic self-care activities were a predictor for psychiatric symptoms (measured by BPRS) at discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.091, F = 8.496, p = 0.005), whereas a combined group of badminton and Tai Chi was a predictor for general activity motivation (measured by GAMM) at 1 month after discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.047, F = 4.697, p < 0.05), and soccer alone was a predictor for somatic health (measured by PHQ-15) at 1 month after discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.06, F = 5.784, p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Participating in activities of patients’ own choice and interests is positively associated with patients’ psychiatric and somatic health and subjective wellbeing. Outdoor soccer has added effect on patients’ somatic health. The beneficial effects are maintained at 1 month after discharge. Daily participation of activity meaningful to patients can be a non-pharmacological treatment for patients with SMI to improve somatic and mental health.

Key words: Exercise; Health; Leisure activities; Mental disorders; Mental health

Introduction

Severe mental illness (SMI) is associated with severe chronic somatic illnesses and greater vulnerability to diseases (such as diabetes, coronary heart disease, hypertension, and emphysema),1 likely because of sedentary lifestyle, low motivation, poor dietary habits, and high rate of smoking and drinking.2,3 In addition, antipsychotics may exacerbate somatic health problems and potential health risks. Hence, routine examination of health indices (including somatic health monitoring) is advocated during institutionalisation and primary care settings.4,5 Increased provision of somatic health checks for people with SMI may promote their health and wellbeing.6

Psychiatric inpatients are generally not motivated to engage in activities and consider it a less meaningful part of the treatment.7 However, activities may improve the social aspects and the feeling of somatic and mental wellbeing of patients. With the introduction of recovery-oriented practice in mental health service in Hong Kong since 2010, more theme-based or interest-based training activities are provided to foster early rehabilitation in the acute phase of treatment.8 The areas of concern include symptom management, bodily functions, lifestyle, enjoyment, and sports indoor or outdoor. Moreover, patients’ motivation to join is enhanced by choice and peer support.9 Thus, this study aimed to examine associations between SMI, general health symptoms, mental wellbeing, and different activity levels in patients with SMI. The results would inform mental health professionals on the effective scheduling and variety of daily engagement of patients during hospital stay. We hypothesised that patients engaged in meaningful activity and maintained a healthy lifestyle during hospital stay would achieve better somatic and mental health outcome after discharge.

Methods

This study was approved by the Kowloon Central / Kowloon East Cluster Research Ethics Committee (KC/ KE-14-0083/ER-2). Consecutive patients with SMI referred for occupational therapy between August 2014 and August 2015 in a regional psychiatric hospital who can read and write traditional Chinese and follow instructions with minimal disturbing behaviours were assessed on admission and at discharge by occupational therapists and were invited for telephone follow-up by a research assistant at 1 month after discharge. Those with mental handicapped, personality disorder, sexual disorder, or cognitive impairments were excluded.

Their hours of activities per day during hospital stay were recorded as <1 hour, 1-3 hours, and >3 hours in three categories: basic self-care activities, interest-based activities (watching television, doing simple craftwork, reading newspapers, and playing outdoor sports activities such as soccer, badminton, and Tai Chi), and role-specific or life- goal-oriented activities (eg, domestic work training, work- related training selected by the patient and case therapist). Patients were free to join or decline any activities.

Patients’ somatic and mental health were measured at admission, discharge, and 1 month after discharge using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Chinese version of Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (C-SWEMWBS), and Chinese version of General Activity Motivation Measure (GAMM).

The BPRS is used by clinicians or researchers to measure psychiatric symptoms (such as depression, anxiety, hallucinations, and unusual behaviour). Each symptom is scored from 1 to 7; a total of 24 symptoms yield a highest possible score of 168.10

The PHQ-15 is self-administered for primary care evaluation of mental disorders. It is derived from the original PHQ studies of 6000 patients for assessment of somatic symptom severity and the potential presence of somatisation and somatoform disorders. Each of the 15 items is scored from 0 to 2, with a total score of 0 to 30. A cut-off score of 5, 10, and 15 represents mild, moderate, and severe levels of somatic health.11

The PSQI is used to assess sleep quality. It contains 19 self-rated questions that measures seven components of sleep: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty); the sum of the seven component scores yields a global score of 0 (no difficulty) to 21 (severe difficulty).12

The C-SWEMWBS is an ordinal scale comprising seven positively phrased items about mental wellbeing. Responses are rated on a Likert scale ranging from ‘none of the above’, ‘rarely’, ‘some of the time’, ‘often’ to ‘all of the time’. Total score ranges from 7 to 35; a higher score indicates a higher level of mental wellbeing. The scale has been validated in Hong Kong people with SMI, with good psychometric properties and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.13

The Chinese version of GAMM14 is cross-culturally adapted and validated in Hong Kong.15 It is a self-reported scale comprising 13 questions preceded by “How important is it for you to…?”: (1) put your skills to use on a regular basis, (2) keep a flexible schedule, (3) contribute to the community, (4) receive appreciation from other people for what you do, (5) avoid taking on new responsibilities, (6) be free to do the things that you enjoy, (7) make new friends, (8) do things at your own pace, (9) have interesting new experiences, (10) get out of the house regularly, (11) choose the people with whom you associate, (12) feel that you have accomplished something every day, and (13) find ways to save money. Responses are rated on a Likert scale of 1 (not important) to 5 (very important). Higher scores indicate more motivated in general activity. It has good Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86 and good test-retest reliability of 0.587 (p = 0.005).15

It is estimated that 32% of patients with SMI had minimal activity level.9 Assuming a relative risk of 2, with 50% of the true value, 95% confidence interval, and 30% drop-out rate, a sample size of 44 patients is required in each of three types of activities. A total of 350 patients were screened for recruitment on admission. Independent variables were daily hours in the three types of activities. Dependent variables were changes in mental and physical health at the three time-points. Correlations between health measures and demographics and activity types and intensity were explored. Non-parametric tests were used to compare across activity types and intensity and health outcomes across different time points. Linear regression analysis was used to determine significant contributing factors. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 350 patients screened on admission, 133 were assessed on discharge. Of them, 84 (35 men and 49 women) aged 16 to 63 years were followed up by telephone at 1 month after discharge. 67 (78.9%) of them were single or divorced. 66 (77.6%) were living with their family. 50 (58.8%) were unemployed and 21 (24.7%) were employed before admission. 64.7% completed secondary level of education. The mean psychiatric admission history was 9.14 years, and the mean length of hospital stay of current admission was 74.73 days. The most common diagnosis was schizophrenia (n=35), followed by depression (n=15), psychosis (n=14), bipolar affective disorder (n=10), others (n=8), and delusional disorder (n=2) [Table 1].

The mean total hours of activities per person was 83.57 ± 128.403 (range, 1-705) for basic self-care activities, 190.68 ± 287.76 (range, 0-1400) for interest- based activities), and 182.2 ± 348.68 (range, 0-1737) for role-specific activities. The hours of activities per day was <1 hour in 32 (38.1%) patients, 1-3 hours in 34 (40%) patients, and >3 hours in 18 (21.2%) patients (Table 2). 51.4% of patients with schizophrenia had <1 hour per day in activities, whereas only 20% of patients with depression had <1 hour per day in activities. Overall, 78.6% of patients had at least 3 hours per day in activities. Specifically, 22.9% of patients with schizophrenia and 46.7% of patients with depression had >3 hours per day in activities. 22 (26.19%) patients joined outdoor sports activities. Of them, 17 played soccer for a mean of 2.51 ± 8.048 (range, 2-43) hours and four played badminton and/or Tai Chi (range, 2-17 hours).

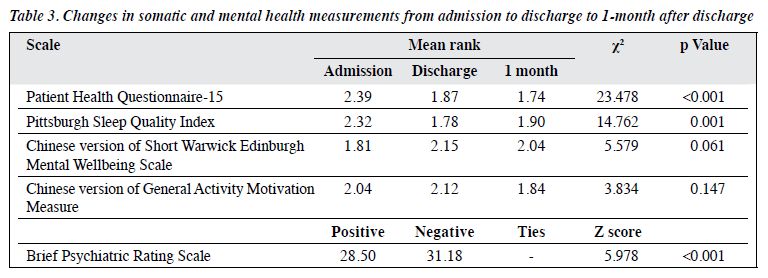

Improvement in somatic and mental health was positively associated with hours of activities per day. Activities were associated with reduced psychiatric symptoms (measured by BPRS) at discharge (Z = 5.978, p < 0.01, Wilcox signed rank test). Similar results were achieved by the Friedman two-way analysis of variance by ranks across three time-points. Activities were associated with less somatic complaints (measured by PHQ-15) [χ2.= 23.478, p < 0.01], better sleep quality (measured by PSQI) [χ2 = 14.762, p < 0.01] (Table 3). However, the improved subjective wellbeing score (measured by C-SWEMBS) at discharge (Z = -2.184, p < 0.05) could not be maintained after 1 month (χ2 = 5.579, p = 0.061). The BPRS score for psychiatric symptoms at discharge was inversely associated with C-SWEMWBS score for mental wellbeing (r = -0.233, p = 0.033) and C-GAMM score for activity motivation (r = -0.258, p = 0.018). These measures for somatic and mental health were not associated with diagnosis, psychiatric history, age, education, or other demographics.

Using the Spearman’s rho correlation, the BPRS score for psychiatric symptoms at discharge was associated with basic self-care activities (r = 0.231, p = 0.043) and interest- based activities (r =0.266, p = 0.014) [Table 4]. Playing soccer was associated with both PHQ-15 score for somatic health (r = -0.393, p < 0.001) and C-SWEMWBS score for mental wellbeing (r = 0.229, p = 0.039) at discharge and 1-month follow-up. PSQI score for sleep quality at 1 month was associated with basic self-care activities (r = -0.223, p = 0.043). All three intensity levels of activity were associated with increased mental wellbeing (measured by C-SWEMWBS) [χ2 = 7.177, p < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis test].

In linear regression analysis using the forward stepwise method, basic self-care activities were a predictor for psychiatric symptoms (measured by BPRS) at discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.091, F = 8.496, p = 0.005), whereas a combined group of badminton and Tai Chi was a predictor for general activity motivation (measured by GAMM) at 1 month after discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.047, F = 4.697, p < 0.05), and soccer alone was a predictor for somatic health (measured by PHQ-15) at 1 month after discharge (adjusted R2 = 0.06, F = 5.784, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Patients’ somatic and mental health were positively associated with all three types of activities during hospital stay. The effect of outdoor sports activities was not significant owing to the small sample size, but playing soccer was a predictor for somatic health, and a combined group of badminton and Tai Chi was a predictor for motivation. We invited local professional football school to provide regular training to our patients with SMI. Higher intensity of activity participation was associated with greater improvement in health outcomes. The lasting effect of improved subjective mental and physical wellbeing up to 1 month after discharge was consistent with the findings reported in psychiatric rehabilitation.16 Psychiatric symptoms (measured by BPRS) were highly associated with physical and mental health. This supports the postulation that improving mental wellbeing of patients with SMI may have effects on improving somatic health and coping with psychiatric symptoms.13

Occupational therapy uses all forms of activities of daily living as interventions for psychiatric rehabilitation. However, few studies have quantified and categorised the effect of activities on enhancing health in patients with SMI.17 All forms of engagement contribute to non- pharmacological allied treatment for psychiatric and somatic health during the acute phase.17 With the recovery-oriented practice in psychiatric hospitals, occupational therapy plays important roles in the provision of therapeutic activities for resuming healthy living and active participation after discharge, and allowing patients to choose the activities they prefer, rather than being prescribed by therapists or ward staff. This eliminates the effect of initiation by staff, which is perceived as a requirement for treatment compliance, rather than being active to improve own health.18 Further study is warranted to confirm that allowing patients to make choice is an important component of motivation to switch from basic self-care activities to purposeful activities and to increase hours of participation.

The somatic health of people with SMI is commonly overlooked, resulting in disparities and limited access to health services. The present study showed positive associations between motivation and somatic health through activities (ie, soccer), consistent with a study reporting that physical activities result in decreased illness symptoms in 57.4% of patients, with only a few reported negative effects.19 Preventable health conditions lead to premature mortality in people with SMI and reduce their life span by 10 to 20 years.20 Furthermore, people with SMI are more likely to engage in lifestyle behaviours (such as tobacco consumption, somatic inactivity, and unhealthy diets) that increase the risk of non-communicable diseases. Hence, it is important for people with SMI to participate in outdoor sports and recreational activities to increase motivation to be active.

Development of healthy lifestyle is already applied in outpatient psychiatric rehabilitation programmes. Continued engagement in activities after discharge can re- mediate the reduction of the wellbeing score and motivation score after discharge.21 Our patients were encouraged to take a more active role when choosing activities. Cultivating this attitude early in the acute admission stay period is beneficial, especially for those with depression or adjustment disorders who have higher functioning and are usually discharged to the community without undergoing extensive rehabilitation programmes.

This study has limitations. The sample was collected in a single hospital and thus the results may not be generalised to the entire psychiatric population. The study was not conducted under a controlled environment, owing to limitations in acute ward settings. Measurement bias in recording activities by ward assistant may have occurred. Confounders (patients’ lifestyle, experience of activities, level of social skills, and prevailing negative symptoms) were not controlled and may have resulted in patients’ selection bias of activities.

Conclusion

Participating in activities of patients’ own choice and interests is positively associated with patients’ psychiatric and somatic health and subjective wellbeing. Outdoor soccer has added effect on patients’ somatic health. The beneficial effects are maintained at 1 month after discharge. Daily participation of activity meaningful to patients can be a non-pharmacological treatment for patients with SMI to improve somatic and mental health.

References

- McCreadie RG, Kelly C. Patients with schizophrenia who smoke. Private disaster, public resource. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:109. Crossref

- Brown S, Birtwistle J, Roe L, Thompson C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1999;29:697-701. Crossref

- Cormac I. Promoting healthy lifestyles in psychiatric services. In: Physical health in mental health. Final report of a scoping group. Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2009:62-70.

- Marder SR, Essock SM, Miller AL, Buchanan RW, Casey DE, Davis JM, et al Physical health monitoring of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1334-49. Crossref

- Minsky S, Etz RS, Gara M, Escobar JI. Service use among patients with serious mental illnesses who presented with physical symptoms at intake. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:1146-51. Crossref

- Patil S, Sain K. Why physical health checks for mental health patients are vital to their wellbeing. https://www.hsj.co.uk/service-design/why- physical-health-checks-for-mental-health-patients-are-vital-to-their- wellbeing/5039211.article

- Nyboe L, Lund H. Low levels of physical activity in patients with severe mental illness. Nord J Psychiatry 2013;67:43-6. Crossref

- Chao J, Lee S, Huang T, Yeung O, Leung T, Lee L, et al. The impact of teaching illness management to psychiatric in-patients. A one-year follow-up. Hong Kong Hospital Authority Convention; 2013.

- Vancampfort D, Probst M, Knapen J, Carraro A, De Hert M. Associations between sedentary behaviour and metabolic parameters in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Res 2012;200:73-8. Crossref

- Maruish ME. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1999.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002;64:258-66. Crossref

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193-213. Crossref

- Ng SS, Lo AW, Leung TK, Chan FS, Wong AT, Lam RW, et al. Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the short Warwick- Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale for patients with mental illness in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:3-9. Crossref

- Caro FG, Burr JA, Caspi E, Mutchler JE. Motives that bridge diverse activities of older people. Act Adapt Aging 2010;34:115-34. Crossref

- Ng SSW, Chan MKL, So CT, Chin AMH. Understanding general activity motivation for persons with stroke – a reversal theory perspective. Res Health Sci 2016;1:5-13. Crossref

- Young KW, Ng P, Pan J. Functional recovery of consumers discharged from mental hospital and participating in a community- based psychosocial programme provided by a non-governmental organisation. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2014;24:139-47.

- Gibson RW, D’Amico M, Jaffe L, Arbesman M. Occupational therapy interventions for recovery in the areas of community integration and normative life roles for adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther 2011;65:247-56. Crossref

- McDevitt J, Snyder M, Miller A, Wilbur J. Perceptions of barriers and benefits to physical activity among outpatients in psychiatric rehabilitation. J Nurs Scholarsh 2006;38:50-5. Crossref

- Sorensen M. Motivation for physical activity of psychiatric patients when physical activity was offered as part of treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:391-8. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Management of Physical Health Conditions in Adults with Severe Mental Disorders. 2018.

- Meyer B. Coping with severe mental illness: relations of the brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2001;23:265-77. Crossref