East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:57-62 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1924

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Chibueze Anosike, M Pharm, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Management, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 410001, Enugu State, Nigeria Deborah Oyine Aluh, M Pharm, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Management, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 410001, Enugu State, Nigeria

Onyinyechukwu Blessing Onome, M Pharm, Lyn-Edge Pharmaceuticals Limited, Port-Harcourt City, Rivers State, Nigeria

Address for correspondence: Chibueze Anosike, Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacy Management, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 410001, Enugu State, Nigeria.

Email: chibueze.anosike@unn.edu.ng

Submitted: 27 March 2019 Accepted: 7 August 2019

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the level of social distance towards people with mental illness among pharmacy students in a Nigerian university and to explore its associated factors.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 433 pharmacy students in University of Nigeria, Nsukka. The 8-item Social Distance Scale was used to assess an individuals’ avoidance reaction directed towards people with mental disorder. Descriptive statistics, Student’s t test, and multivariate logistic regression were used for data analysis.

Results: Overall, the students demonstrated a low social distance towards people with mental illness. Lower social distance towards people with mental disorder was associated with younger students (p = 0.006) and students who have had contact with a person with mental illness (p = 0.026), who have visited a mental hospital (p = 0.019), who have experienced mental illness (p = 0.028), and who know a family member or friend with mental illness (p = 0.015). Independent predictors for high social distance towards people with mental illness were age of ≥25 years (odds ratio = 1.488, p = 0.046) and no prior visit to a mental hospital (odds ratio = 2.676, p = 0.016).

Conclusion: Our pharmacy students had a low social distance towards people with mental illness. Predictors for the low social distance were younger age and previous visits to a mental hospital. We recommend more robust educational and training programme, and increased exposure to clinical clerkship in psychiatry to improve social distance towards people with mental illness among pharmacy students.

Key words: Mental disorders; Nigeria; Social distance; Social stigma; Students, pharmacy

Introduction

Mental illnesses are a source of burden to individuals and society at large. It is estimated that over 450 million people sustain mental illness worldwide. One in four individuals is expected to experience a mental disorder in the course of their life.1 In 2015, mental illness was responsible for 15% of the global disease burden.1 Mental illness is devastating for patients and their families. People with mental disorders need to overcome the clinical symptoms and disabilities associated with the disease,2 in addition to stigma and discrimination accompanying the disease.

People with mental illness are victims of social exclusion and isolation,3,4 and are often denied opportunities to a satisfactory quality of life. Stigma and discrimination are major factors that inhibit people with mental illness from seeking help.5 Unfortunately, healthcare professionals and trainees have been reported to distance themselves from people with mental disorders.6,7 Stigmatising and discriminating behaviours of individuals are measured by proxy through estimation of their social distance towards those with mental illness. Such social distance reflects self-report willingness to participate in different forms of relationships of varying degrees of intimacy with someone who has a defamed identity.8

Stigma and discrimination are important barriers to the provision of effective community mental healthcare.9 Healthcare professionals frequently exhibit negative attitudes towards people with mental disorders.6,10 The attitudes of healthcare professionals may reflect prevailing cultural values, norms, and attitudes within society.11 Pharmacists are among the most frequently consulted healthcare professionals within the communities12 and provide valuable services for patients with mental illness.13 Pharmacists’ willingness to provide pharmaceutical care services for patients with mental illness is associated with their attitudes towards mental illness.14 Therefore, the preparedness of pharmacists to interact with people with mental illness is critical for the provision of adequate and effective mental health services.

Most studies of attitudes of pharmacy trainees towards mental illness are from North America,15,16 Europe,17,18 Asia,19,20 and Oceania.21 Few African studies have reported attitudes and social distance towards mental disorders among carers and patients in Malawi,22 general population in post-conflict South Sudan,23 and university students in Cameroon.24 In Nigeria, social distance towards people with mental illness have been reported among secondary school students,25 undergraduate students,26 lay public,27 health workers, and relatives of patients with mental illness.28,29 However, no study in Nigeria has assessed the attitudes of pharmacy students towards people with mental illness. Pharmacy students are future healthcare providers; measuring their social distance towards mental illness might uncover educational opportunities necessary to improve the care of patients with mental illness.30 Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the level of social distance towards people with mental illness among pharmacy students in a Nigerian university and to explore its associated factors.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was approved by the Human Experimentation Ethical Committee of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (registration number: UN/VCO/ HEEC/02/12044). Undergraduate pharmacy students at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka were conveniently drawn proportionately across different classes to ensure fair representation. The total number of pharmacy students at the time of the study was 1188. Using a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval, the minimum sample size required was determined to be 291 via an online Raosoft sample size calculator. To improve the statistical power, 452 students were selected at random.

Data collection was done in June 2018. Oral informed consent was obtained from each participant before study initiation. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any point. Participants were assured that information provided would be held in confidence and only reported as group data. Participants were briefed by the lead researcher on the aims and protocols of the study. Researchers ensured that participants completed the questionnaire independently of one another. Researchers would provide clarification when necessary. Questionnaires were retrieved immediately after completion. The average time to complete was about 10 minutes.

The 8-item Social Distance Scale was used to assess an individuals’ avoidance reaction directed towards people with mental disorder. Validity and reliability of the instrument has been proven.15,20,30 A pilot study on 20 students was conducted to re-validate the instrument in the study population. Its internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.758) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) were within acceptable limit. Each item is rated in a 3-point Likert scale (agree, not sure, disagree). Items are a combination of positively and negatively worded questions. Favourable responses are ‘agree’ on some items and ‘disagree’ on others. Favourable responses are assigned ‘1’, not sure responses are assigned ‘2’, and unfavourable responses are assigned ‘3’. Total possible scores range from 8 to 24; lower scores indicate less avoidance towards people with mental illness.

In addition, demographic characteristics of participants were collected, including sex, age, level, marital status, and place of residence. Participants were grouped into junior level (years 1-2) and senior level (years 3-5) based on whether they have been exposed to clinical training. Students were also required to provide a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response to the following four questions: (1) Have you had contact with a person with mental illness? (2) Have you visited a mental hospital? (3) Have you experienced mental illness? and (4) Do you know a family member/friend with mental illness?

Data analysis was performed using SPSS (Windows version 21; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Demographic characteristics and item responses were presented as frequency and percentage, or mean and standard deviation. Independent Student’s t test was used to determine factors associated with social distance towards people with mental illness. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine variables that independently predict high social distance from people with mental disorders. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 452 students participated, 443 completed the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 98.0%. 54.2% were female; 85.3% were aged 18 to 25 years; 68.4% were senior level; 95.5% were single; and 50.6% were residing at campus hostels. 63.9% had contact with people with mental illness, but only 20.5% visited a mental hospital. 4.7% had experienced a mental illness, and 43.6% reported knowing a family member/friend with mental illness.

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of responses to items in the Social Distance Scale. 58.5% disagreed that it was wrong to shy away from people who have had a mental disorder. 45.4% reported that they would feel uncomfortable living near someone who had visited a mental hospital. Approximately 50% admitted that they would not hire someone nor allow any of their daughter to marry a man who had visited a mental hospital. Overall, 57.8% demonstrated a low social distance towards people with mental illness.

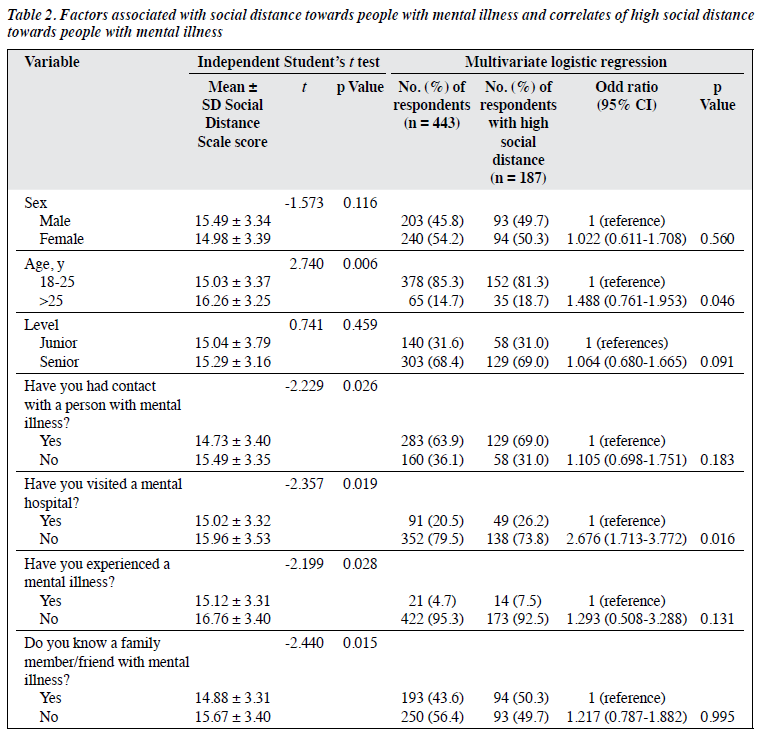

Lower social distance towards people with mental disorder was associated with younger students (p = 0.006) and students who have had contact with a person with mental illness (p = 0.026), who have visited a mental hospital (p = 0.019), who have experienced mental illness (p = 0.028), and who know a family member or friend with mental illness (p = 0.015) [Table 2].

Multivariate logistic regression showed that students aged ≥25 years had about 1.5 times higher odds of demonstrating high social distance towards persons with mental illness, compared with younger students (odds ratio [OR] = 1.488, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.761- 1.953, p = 0.046, Table 2). Students who have not visited a mental hospital had approximately 2.7 times higher odds of demonstrating high social distance towards persons with mental illness, compared with students who have visited a mental hospital (OR = 2.676, 95% CI = 1.713-3.772, p = 0.016, Table 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was the first to evaluate the social distance towards persons with mental illness among pharmacy students of a Nigerian university and to explore the associated factors. Our participants showed less tendency to stigmatise and discriminate against individuals with mental health disorders. They were more cooperative, considerate, and sympathetic towards the people with mental illness. Previous studies have documented a combination of high and low social distance towards people with mental illness among pharmacy students. In the United States, social distancing is prominent among student pharmacists.30 >85% of the students stated that they would be unwilling to work with someone with mental illness or to have the person as a neighbour or a babysitter for his or her child. However, other studies found a lower tendency to stigmatise people with mental illness among pharmacy students.15,20,31 In contrast, studies in Nigeria reported high social distance towards people with mental illness among undergraduate students (65.1%) and lay public (60.9%) in South West Nigeria.26,27,32 Also, about 82% of secondary school students in South West Nigeria would not marry someone with mental illness, and about 62% would be disturbed if they are to share a room with someone with a mental disorder.25 However, about 64% of our pharmacy students have had contact with people with mental illness, and this appeared to decrease social distance towards people with mental illness. Knowledge contact-based anti-stigma programme has been reported to improve mental health literacy and reduced stigma perceived among adolescents and adults in China.33 Also, 43.6% of our pharmacy students had a family member or friend with a mental disorder. It is believed that more contact with persons with mental illness leads to less stigmatisation against them. Most students in the current study were eager to identify with those who have visited psychiatric hospital or who have previous history of mental illness. This is probably because of improved understanding, tolerance, and sympathy towards people with the disease.34

Some of our participants have attended lectures and training on mental health literacy. Medical students have lower social distance towards people with mental illness, compared with non-medical students.27 Nonetheless, our findings underscore the need for improved awareness and knowledge of mental disorders among pharmacy students, considering the gaps in attitudes and opinions between different groups.

In the present study, social distance towards people with mental disorder was associated with students’ age, contact with people with mental illness, visit to a mental hospital, personal experience of mental disorder, and knowing a family member or friend with a mental illness. Nevertheless, only older age and not visiting a mental hospital were independent predictors for high social distance towards people with mental illness. Several studies have reported greater social distance towards people with mental illness among older adults than younger adults.34-36

In a study of three communities in South West Nigeria, older respondents demonstrated a significantly higher desire for social distance towards persons with mental illness compared with those younger.27 A Malawian study reported comparable findings.22 In addition, people who have experienced mental illness or who have a family member or friend with a mental illness often express favourable attitudes towards people with mental illness.15,20,27,31 On the contrary, among student pharmacists in Estonia, family experience of mental illness was not predictive of low social distance.18 Similarly, pharmacy trainees in Nepal who had experience of mental disorder or who had a family member with a mental disorder were more likely to discriminate against people with mental illness.19 Nonetheless, among community residents in South Sudan, familiarity with mental illness was not associated with social distance.23 Our findings suggest that increasing familiarity and contact with people with mental illness improves social distance towards them.34

We recommend instituting a more robust educational and training programmes to improve attitudes of pharmacy students towards patients with mental illness. Curricula of pharmacy should include psychiatric and mental health content. Usual classes on pharmacological treatment of mental disorders and counselling skills are insufficient to equip pharmacists to provide mental health services. Therefore, increased exposure of pharmacy students to clinical clerkship in psychiatry is recommended, as familiarity and contact with people with mental illness was demonstrated to improve students’ attitudes. In addition, simulations to mimic real patients with mental disorders during normal class sections on psychiatry and mental health are recommended. Further studies are needed to investigate whether pharmacy students’ desire for social distance towards people with mental illness translates to poor provision of mental health services during practice.

Our study had some limitations. First, this study was conducted among pharmacy students at a university in Nigeria. Generalisation of our findings to other schools of pharmacy with a comparable background and demographic characteristics could not be ascertained. Second, there may have been social desirability bias among the students even though the responses were anonymous. Some students may have under-reported past experience of mental illness or knowledge of a family member with a mental disorder. Similarly, some students who may have indicated willingness to cooperate and interact with people with mental illness may not necessarily do so in real life. Finally, the cross-sectional design cannot determine causal relationships between social distance and demographic factors.

Conclusion

Our pharmacy students had a low social distance towards people with mental illness. Predictors for the low social distance were younger age and previous visits to a mental hospital. We recommend more robust educational and training programme, and increased exposure to clinical clerkship in psychiatry to improve social distance towards people with mental illness among pharmacy students.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental disorders affect one in four people. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/media_centre/press_ release/en/ Accessed 15 December 2018.

- Rüsch N, Angermeyer M, Corrigan P. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:529-39. Crossref

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self- esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1621-6. Crossref

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002;1:16-20.

- Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:51-4. Crossref

- Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophr Bull 2006;32:709-14. Crossref

- Reavley NJ, Mackinnon AJ, Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. Stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental disorders: a comparison of Australian health professionals with the general community. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014;48:433-41. Crossref

- Wark C, Galliher JF. Emory Bogardus and the origins of the Social Distance Scale. Am Sociol 2007;38:383-95. Crossref

- Sartorius N. Stigma and mental health. Lancet 2007;370:810-1. Crossref

- Grausgruber A, Meise U, Katschnig H, Schöny W, Fleischhacker WW. Patterns of social distance towards people suffering from schizophrenia in Austria: a comparison between the general public, relatives and mental health staff. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007;115:310-9. Crossref

- Patel MX. Attitudes to psychosis: health professionals. Epidemiol Psychiatr Soc 2004;13:213-8. Crossref

- Jesson J, Bissell P. Public health and pharmacy: a critical review. Crit Public Health 2006;16:159-69. Crossref

- Scheerder G, De Coster I, Van Audenhove C. Pharmacists’ role in depression care: a survey of attitudes, current practices, and barriers. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:1155-60. Crossref

- Rickles NM, Dube GL, McCarter A, Olshan JS. Relationship between attitudes toward mental illness and provision of pharmacy services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2010;50:701-13. Crossref

- Jermain DM, Crismon LM. Students’ attitudes toward the mentally ill before and after clinical rotations. Am J Pharm Educ 1991;55:45-8.

- Einat H, George A. Positive attitude change toward psychiatry in pharmacy students following an active learning psychopharmacology course. Acad Psychiatry 2008;32:515-7. Crossref

- Bell JS, Aaltonen SE, Bronstein E, Desplenter FA, Foulon V, Vitola A, et al. Attitudes of pharmacy students toward people with mental disorders, a six country study. Pharm World Sci 2008;30:595-9. Crossref

- Volmer D, Mäesalu M, Bell JS. Pharmacy students’ attitudes toward and professional interactions with people with mental disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2008;54:402-13. Crossref

- Panthee S, Panthee B, Shakya SR, Panthee N, Bhandari DR, Bell JS. Nepalese pharmacy students’ perceptions regarding mental disorders and pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ 2010;74:pii:89. Crossref

- Cates ME, Bright JT, Kamei H, Woolley TW. Attitudes of Japanese pharmacy students towards mental illness. Pharm Educ 2011;11:132-5.

- Bell JS, Aaltonen SE, Airaksinen MS, Volmer D, Gharat MS, Muceniece R, et al. Determinants of mental health stigma among pharmacy students in Australia, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, India and Latvia. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2010;56:3-14. Crossref

- Crabb J, Stewart RC, Kokota D, Masson N, Chabunya S, Krishnadas R. Attitudes towards mental illness in Malawi: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:541. Crossref

- Ayazi T, Lien L, Eide A, Shadar EJ, Hauff E. Community attitudes and social distance towards the mentally ill in South Sudan: a survey from a post-conflict setting with no mental health services. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;49:771-80. Crossref

- Nguendo-Yongsi HB. Knowledge and social distance towards mental disorders in an inner-city population: case of university students in Cameroon. Trends Med Res 2015;10:87-96. Crossref

- Adeosun II, Fatiregun O, Adeyemo S. Social distance towards people with HIV-AIDS versus mental illness in a sample of adolescent secondary students in Lagos Nigeria. J Educ Soc Behav Sci 2017;22:1-7. Crossref

- Adewuya AO, Makanjuola RO. Social distance towards people with mental illness amongst Nigerian university students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:865-8. Crossref

- Adewuya AO, Makanjuola RO. Social distance towards people with mental illness in southwestern Nigeria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2008;42:389-95. Crossref

- Aina OF, Oshodi OY, Erinfolami AR, Adeyemi JD, Suleiman TF. Non- mental health workers’ attitudes and social distance towards people with mental illness in a Nigerian teaching hospital. S Sudan Med J 2015;8:57-9.

- Chukwujekwu DC, Chukwujekwu JC, Olose EO. Comparison of degrees of social distance towards the mentally ill between relatives of psychiatric patients, health workers and the general public. Am J Psychiatr Neurosci 2016;4:48-51. Crossref

- Seaton V, Piel M. Student pharmacists’ social distancing toward people with mental illness. Ment Health Clin 2018;7:181-6. Crossref

- Crismon ML, Jermain DM, Torian SJ. Attitudes of pharmacy students toward mental illness. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47:1369-73. Crossref

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:219-25. Crossref

- Fung E, Lo TL, Chan RW, Woo FC, Ma CW, Mak BS. Outcome of a knowledge contact-based anti-stigma programme in adolescents and adults in the Chinese population. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:129-36.

- Jorm AF, Oh E. Desire for social distance from people with mental disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:183-200. Crossref

- Liekens S, Smits T, Laekeman G, Foulon V. Factors determining social distance toward people with depression among community pharmacists. Eur Psychiatry 2012;27:528-35. Crossref

- Yuan Q, Abdin E, Picco L, Vaingankar JA, Shahwan S, Jeyagurunathan A, et al. Attitudes to mental illness and its demographic correlates among general population in Singapore. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167297. Crossref