East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:150-8 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1844

THEME PAPER

Verity Chester, BSc, MSc, St Johns House, Palgrave, Diss, Norfolk, United Kingdom

Address for correspondence: VerityChester,Research and Projects Associate, St Johns House, Lion Road, Palgrave, Diss, Norfolk, IP22 1BA, United Kingdom.

Email: veritychester@priorygroup.com

Submitted: 1 May 2018; Accepted: 4 September 2018

Abstract

This review aims to describe the way in which people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD) are treated within the criminal justice system (CJS) in the United Kingdom (UK). The relevant empirical literature and national reports are reviewed, and the current care model for offenders with IDD described. The care of people with IDD within the CJS is relatively advanced in UK; however, offenders with IDD experience difficulties at all stages. This includes engagement with police and the courts, accessing adapted therapies, and after discharge from inpatient care or release from custody. This review highlights a number of strengths of the existing model of care, as well as ongoing challenges. Care of people with IDD within the CJS is highly political, and many aspects of the current model operate according to government policy, based upon charitable or independent review evidence, rather than empirical research. Further research on people with IDD in the CJS is urgently needed, to fully understand the factors related to treatment outcomes.

Key words: Autism spectrum disorder; Autistic disorder; Intellectual disability; Mental disorders; Neurodevelopmental disorders

Background

The community care movement led to the closure of long-stay institutions that used to accommodate large numbers of people with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (IDD) such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in the United Kingdom (UK)1, and indeed, worldwide. Deinstitutionalisation involved moving people out of large campuses into community settings, such as group residential homes, supported living accommodation, family homes or independent living.2 The vast majority of adults with IDD live fairly independent, law-abiding lives in the community. However, a minority of people engage in behaviour which comes to the attention of the criminal justice system (CJS). There are two key principles that underpin the way in which people are treated within the UK CJS: justice and rehabilitation.3 These principles are the same for people with IDD; yet, for this group, the concept of equality is also relevant, in that justice is equally as important for victims of crimes perpetrated by people with IDD, and that rehabilitation should be equally accessible for people with IDD.

The aim of the law is to maintain social order in the interests of the community. The CJS has both preventative (ie, deterrent) and punitive functions that arise from the rights of the state to impose sanctions on those who violate criminal law.4 In regard to offending behaviour, the term ‘rehabilitation’ refers to social reintegration, and this reintegration includes the avoidance of further crime. Rehabilitation involves an intervention, or combination of interventions which reduces an offender’s further criminal activity, by addressing individualised or known general risk factors for offending.4 Commonly considered risk factors include substance misuse, lack of employment, comorbid mental disorder, or violent attitudes.5 Addressing these areas in offenders with IDD can be challenging, owing to a lack of accessible self-report assessments, a lack of adapted manualised psychological programmes, and the level of clinical complexity of people with IDD.6

In order to improve this situation, the UK has a well- established network of stakeholders who are committed to developing understanding of this under-researched population. The UK was host to the first academic journal dedicated to this field,7 an annual conference on the topic is a regular success, and in 2012 a clinical research group was set up to bring together patients, family carers, and multidisciplinary clinicians and academics, to stimulate research in this area.8 A significant body of research has investigated the characteristics of people with IDD within the CJS,9,10 described adapted psychological treatment programmes designed to rehabilitate,11,12 and assessed how to best evaluate treatment outcomes.13,14 Nevertheless, people with IDD remain a vulnerable group. In 2009, the Bradley Report, which focused on people with mental health problems or IDD in the CJS was published.15 Around the same time, Talbot16 published a review entitled “No One Knows” for the Prison Reform Trust, a charitable organisation in the UK. Both of these reviews highlighted a number of issues that particularly affect this population prior to, and during involvement within the various stages of the CJS, and made pivotal recommendations for improvement. A follow-up project found that many of the recommendations of the Bradley Report had not been implemented.17

Prior to Involvement with the Criminal Justice System

The term ‘offending behaviour’ is problematic when used in relation to people with IDD.18 The dividing line between ‘challenging behaviour’ and ‘offending behaviour’ is often blurred.19 Challenging behaviour is defined as behaviour ‘of such an intensity, frequency or duration as to threaten the quality of life and/or the physical safety of the individual or others and is likely to lead to responses that are restrictive, aversive or result in exclusion’.18 Under English law (applied in England and Wales), a crime is defined by two components: actus reus (the act of crime) and mens rea (the intent to commit that crime). The latter can be difficult to elicit in people with IDD (especially in those with moderate to profound ID) and is a key issue when it comes to legal perception of the difference between challenging behaviour and criminal behaviour,19,20 and when ascertaining legal responsibility.4

This area is complex, and offending behaviour can be said to be both over- and under-reported and processed among people with IDD. In terms of under-reporting, family and paid carers of people with IDD can be less likely to involve the police when an offence is committed.21 The availability of community IDD forensic teams can also affect whether behaviour reaches the attention of police.22 These teams provide interventions and manage risk in the community setting, avoiding the need for further processing by the CJS. The police, the crown prosecution service or other criminal justice agencies may decide not to take the case through the courts, or even drop proceedings altogether, once they see that the person they are pursuing is receiving supervision within a care setting. In some instances, offending behaviour is managed solely within care settings. Thus when a person has moderate to severe IDD, unless the criminal act is very serious, they are unlikely to be dealt with through the CJS.20 Conversely, it has been suggested that people with IDD can have a lesser ability to conceal their actions, and are more likely to be caught and arrested for their crimes when they do occur.23 However, the issue becomes far less clear for people with mild IDD, where both their understanding of the offence and the appropriateness of them being dealt with through either the health service or the CJS requires specialist evaluation.20

During Involvement with the Criminal Justice System

Challenges become evident for defendants with IDD once their behaviour has come to the attention of the various stages of the CJS; engagement with the police, courts, prison and diversion services. In order to achieve justice, a number of safeguards must be put in place when interacting with defendants with IDD. Many of the issues, such as communication and access, affect the defendant at multiple stages, yet will be discussed separately due to the various supportive measures and interventions available at each domain in the UK. If these processes are not followed, serious consequences can arise, such as miscarriages of justice, or inappropriate sentencing, which affect the principles of justice and rehabilitation.

Police

Studies have suggested that between 5% to 9% of suspects seen at police stations have IDD.16 Reports relating to the prevalence of IDD (such as ASD) among defendants in the CJS are lacking.24 A number of miscarriages of justice have shown that suspects with IDD are disadvantaged if they are interviewed by the police, because they may ‘without knowing or wishing to do so, be particularly prone in certain circumstances to provide information which is unreliable, misleading or self-incriminating’.25 In England and Wales, The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 198425 covers the powers and duties of the police. The Code of Practice26 specifies that when a person is brought to or arrested at a police station, he or she must first be cautioned. Following this, the individual must be informed verbally by the custody officer of their rights: to obtain legal advice, to have someone informed of the arrest, and to consult the Code of Practice.26 Then, a written leaflet (the ‘Notice to Detained Persons’) is normally presented, reiterating and expanding upon the information already given verbally and explaining the right to a copy of the Custody Record. Research has suggested that few people with IDD understand the information given to them about the caution and their rights in police detention, and are thus likely to be subsequently disadvantaged in accessing the safeguards designed to support them, or their right to apply for bail.27,28

Being interviewed by the police can be a frightening experience for many people; these feelings can be multiplied for people with IDD who may not understand the legal proceedings.29 People with IDD have been demonstrated to be prone to suggestibility, confabulation, acquiescence and compliance, leaving them vulnerable to making false confessions.27,30,31 People with ASD face considerable difficulties in understanding and coping with police demands, and may experience high levels of distress during an interrogative interview.32 The Code of Practice26 recommends that people with IDD have the right to have an appropriate adult in attendance at the police interview, in addition to legal representation. The appropriate adult should: ensure the detainee understands what is happening to them; support them during questioning; assist with communication; observe whether the police are acting fairly and with respect for the detainee’s rights; and ensure the detainee understands their rights and the appropriate adult’s role in protecting them. The appropriate adult safeguard is particularly important for those who may have a limited understanding of their rights, or of the significance of police questions (and of their replies),33 and who may unwittingly provide unreliable or incriminating information.24,34

Despite the advantages described above, the appropriate adult safeguard has received criticism. Concerns have been raised that appropriate adults are not necessarily appropriately trained or skilled to facilitate communication between the police and a suspect with IDD.29 Some police suspects have expressed dissatisfaction with the support given by an appropriate adult during an investigative interview.35 The provision of an appropriate adult is dependent on the defendant being correctly identified as having IDD. This can be problematic, particularly in those with a high level of expressive and receptive communication,24 or in those without dysmorphic features, physical disabilities, or specific syndromes such as Down syndrome.36 Screening for IDD is not well established in police stations.37 Research has also suggested that when screening systems are in place in police custody, some people with IDD remain unidentified.38

Courts

Little research has been conducted on the prevalence of IDD among defendants in the UK court system. When a defendant appears in court for the first time, following a decision to charge, knowledge about them is dependent on the strength of the information gathered at the police station and how it is transferred.15 Liaison and diversion schemes at the police station can ensure appropriate assessment and links with services at the court, but their availability varies geographically.15 At trial, IDD may be relevant when assessing whether the defendant has mens rea for the offence, regarding fitness to plead39,40 or the defence of insanity40; and for the provision of courtroom support.

In England and Wales, crimes are tried at either the magistrates or crown court. Some crimes can only be tried at the magistrates court (summary offences), some in only the crown court (indictable offences) and some can be tried in either (either way offences), and their classification is largely dependent on the severity of the crime.40 A magistrates trial is commenced by a summons sent to the defendant, whereas a crown court trial is preceded by a charge. At the commencement of a crown court trial, the defendant hears the charge, and is asked to plead either guilty, or not guilty. It is possible for the defendant’s barrister to claim that their client is unfit to plead at this stage.40

Mens rea

Although many crimes do not, serious crimes, such as murder, rape, and violence against the person, involve a mens rea. Usually, mens rea involves the defendant intending a consequence (meaning to produce a result, or realising that the result is virtually certain), or recognising the risk of the consequence, and taking the risk anyway.40 Ascertaining mens rea in a case involving a person with IDD can be a core part of the case and its outcome.

Fitness to plead

Accurate identification of people with IDD is also needed to ascertain whether they are fit to plead. In England and Wales, the concept of fitness to plead refers to whether the defendant is mentally capable of fairly standing trial, that is, is able to adequately comprehend the course of the proceedings.39,40 The main criteria used in determining fitness to plead are: capacity to plead with understanding; ability to follow the proceedings; knowing that a juror can be challenged; ability to question the evidence; and ability to instruct counsel.

The question of fitness to plead may be raised by the prosecution, defence or judge. The defendant may be remanded to hospital for evaluation within a psychiatric setting (using Section 35 of the Mental Health Act).41 The defendant may also be remanded for treatment while awaiting trial by the Crown Court (under Section 36 of the Mental Health Act).41 The defendant’s fitness to plead is decided by the judge, without a jury, on the basis of evidence submitted by two or more medical practitioners.16 If a defendant is found to be fit to plead, the case will continue, and the judge may choose to make certain forms of support available for the defendant.16 If a defendant is found to be unfit to plead, a ‘trial of the facts’ may be held, at which the jury decides whether or not the defendant committed the act or omission of which they have been accused.16 Following the trial of the facts, the court can make one of the following orders: an admission order to such hospital as the Secretary of State specifies; a guardianship order under the Mental Health Act (1983)41; a supervision and treatment order; or an order for the defendant’s absolute discharge.42

The defence of insanity, or of diminished responsibility

The defence of insanity relies on principles created by judges in case law following the M’Naghten case in 1843.40 For there to be insanity, the disease of the mind must cause the defendant to have a defect of reason.42 If the defendant has IDD, experts will be sought to provide evidence to the court in each individual case.41 If it is determined that the defendant is guilty by reason of insanity, the judge has access to a range of sentencing options (including hospital, guardianship, supervision and treatment, or absolute discharge orders).42

Diminished responsibility is a defence that can only be used when charged with murder; if successful, the conviction is reduced from murder to manslaughter.41 IDD can be stated as the basis of diminished responsibility. For defences of either insanity or diminished responsibility, the burden of proof is on the defendant (and their legal team) and must be proven on a balance of probabilities and not beyond a reasonable doubt.42

Courtroom support

A defendant can be assessed as fit to stand trial and to enter a plea but may require assistance with understanding the proceedings.42 A number of support arrangements can be put in place to support defendants with IDD during court proceedings. These arrangements support the principle of justice by ensuring the defendant has the right to a fair trial and by avoiding miscarriages of justice, thus limiting the need for an appeal. The arrangement of support within court is dependent on accurate identification of defendants with IDD.

For a defendant with IDD, communication difficulties can be the greatest impediment to effective participation in court proceedings.16 These problems can manifest in the defendant’s ability to understand what is being said in court by the judge, magistrates, lawyers, and others (receptive communication), and to make themselves understood (expressive communication). In England and Wales, the role of the Registered Intermediary was introduced by the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 199943 as one of the special measures available to help facilitate communication between the police, the courts and the vulnerable witness.29 The Registered Intermediary isimpartial; theydonot work for the prosecution or the defence. The Registered Intermediary can assist the police in communicating with witnesses at the investigation stage, take part in pre-trial meetings and court familiarisation visits, and assist communication with the witness at trial.29 Currently, defendants do not have a legal right to a Registered Intermediary; however, the Coroner’s and Justice Bill (2008-09),44 is attempting to amend this situation. As such, the use of Registered Intermediaries with defendants is inconsistent, and use of their services varies across England and Wales.43,45

Sentencing

The first sentencing decision takes place when a defendant appears in court for the first time, and concerns whether to offer bail or to remand in custody.16 If the defendant is found guilty following the trial, there are a number of sentencing options. Sentencing is a key method by which to uphold the principles of justice and rehabilitation. The Criminal Justice Act 200346 sets out the objectives of sentencing: punishment of offenders; reduction of crime (including reduction by deterrence); reform and rehabilitation of offenders; protection of the public; making of reparation by offenders to persons affected by their offences.

It is especially important that the court has access to information on a defendant’s needs at the pre-sentence stage, to inform the sentencing decision through a pre- sentence report prepared by a probation officer. The pre-sentence report contains information about the offence and the background and circumstances of the offender, and includes sentencing recommendations.16 The court can remand the defendant to hospital in order for a report on their mental condition to be prepared (under Section 35 of the Mental Health Act). The report should contain all the necessary information will allow the court to decide on an appropriate disposal or outcome for the defendant.15

Research investigating sentencing practices in relation to people with IDD and those without is lacking in the UK. Ali et al47 reported that people with IDD were over-represented in remand prisoners, compared with people without IDD. The authors attributed this to a lack of understanding and awareness by staff within the CJS about appropriate care pathways for prisoners with IDD, and staff lacking in the skills or competence to work with people presenting with offending behaviour, resulting in people with IDD being left in limbo.47 In regard to ASD, it has been suggested that the courts may misinterpret certain behaviours as lack of empathy and thus sentence people with ASD more harshly.24 However, Esan et al48 reported that inpatients with ASD within an inpatient secure IDD service were more likely to be subject to civil, rather than forensic sections, suggesting their behaviour was managed within the healthcare setting, and less likely to have been processed by the CJS.

Prison

The exact prevalence of people with IDD in prisons in England and Wales is unclear. Estimates from different studies vary according to the type of assessment employed, with screening alone resulting in lower prevalence figures, compared with a full intelligence quotient test alongside adaptive behaviour measures.49 Hayes et al50 completed intelligence quotient assessments on a random sample of prisoners in one UK prison and reported that 7.1% were found to have IDD. Although some prisons have programmes for screening, these are not mandatory and as such, their adoption is inconsistent.51 Furthermore, research examining the utility of screening tools in identifying people with IDD is limited, although developing.52 However, it is widely established that people with IDD are over- represented among prisoners in the UK.52 Specific concerns also exist regarding awareness and identification of people with ASD in prison in England and Wales, because ASD can slip through the gap between IDD and mental health diagnoses, for which more formal assessments have been established, in addition to liaison and diversion schemes.53

Many people with IDD struggle to access services and support within prison owing to difficulties with verbal and written communication.54 For example, prisoners are expected to fill in forms to arrange visits from family members and friends, or to arrange to see a doctor.54 People with IDD are likely to experience greater difficulty coping in prisons, are vulnerable to bullying, financial, physical and sexual abuse, and are at greater risk of attempted suicide.55 There are issues with access to prison treatment programmes, owing to such programmes being designed for people with average intelligence levels.37 Therefore, prison is likely to achieve the aims of justice of punishing the offender, reducing crime, and protecting the public; however, it is unlikely to achieve the aim of rehabilitation of offenders with IDD.

Inpatient Secure IDD Services

Both the Bradley Report15 and Talbot16 recommended that certain suspects and people with IDD should be diverted from the CJS. However, the two reports disagree on the definition of diversion. The Bradley Report15 has a somewhat broad definition of diversion that dates back to a previous review, the Reed Review of Health and Social Services for Mentally Disordered Offenders.56 Reed recommended that liaison and diversion schemes to assess defendants and provide information to the courts should be available at the earliest stage of engagement with the CJS. However, Talbot16 maintains that the purpose of liaison and diversion schemes was originally to identify people whose imprisonment was not in the public interest because, due to their vulnerability, it was likely to be disproportionately harmful, and because prison was an inappropriate setting for vulnerable offenders.

Using the Talbot16 definition, a person may only be diverted from the CJS into the healthcare system following conviction, under sections of the Mental Health Act (1983).41 This diversion can occur at either the court stage, or prisoners may be transferred if their IDD is identified or becomes problematic following being sent to prison. At this time, the person would cease to be known as a “prisoner”, and instead be referred to as a “patient”. If transferred from the court or prison, the majority of patients are admitted under Part III of the Mental Health Act,41 which means they are subject to a court order with or without restrictions from the Ministry of Justice,17 and often referred to as “criminal sections”. Ministry of Justice restricted patients tend to be higher risk, and the government places additional restrictions on their care and treatment, taking some decision making from the responsibility of individual clinicians and teams within services. For example, if a patient were to request hospital leave to attend a funeral, the clinician would write to the Ministry of Justice for their approval, who may grant or decline the leave, or may specify certain criteria, such as the use of handcuffs during escort.

Diversion from the courts or prison is not the only route into an inpatient secure IDD service. The police, the crown prosecution service, or other criminal justice agencies might not take the case through the courts, or might drop proceedings once they see that the person they are pursuing has IDD.57 These situations usually result in an “upwards referral” where patients are referred to services of increasing security, without going through the CJS,57 and are detained under Part II of the Mental Health Act (“civil sections”).41 However, patients in this subgroup often have degrees of “offending-like” behaviour,58 defined as “abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible behaviour” by the Mental Health Act (1983).

Specialist psychiatric services for adults with IDD are a high-profile element of the UK mental health service, with a long history. Diversion into specialist inpatient IDD forensic services (otherwise known as high/medium/low secure units, or forensic psychiatric services) is established best practice for patients with IDD.15,16 These services offer an integrated, multi-disciplinary model of support within an environment that emphasises care and treatment rather than punishment.59 Alexander et al10 described the 10-point treatment programme; an overarching approach to the multidisciplinary assessment and treatment of patients within inpatient secure IDD services. The 10 points include: a multi-axial diagnostic assessment; a psychological formulation; risk assessments; a management of aggression care plan; pharmacotherapy; individual and group psychotherapy, guided by the psychological formulation; offence-specific therapies; education, skills acquisition and occupational/vocational rehabilitation; community participation through a system of graded escorted, shadowed, and unescorted leave periods; and preparation for transition.10 All of the elements of the 10- point treatment programme are provided in a way which is accessible to patients with IDD. For example, offence specific therapies such as the sexual offender treatment programme are adapted to ensure the language used within groups is accessible and utilise frequent repetition of key concepts to support comprehension.60 As such, inpatient secure IDD services are more likely to achieve the aims of rehabilitation.

However, inpatient services for people with IDD and mental health or behavioural problems in the UK have come under scrutiny as a result of an abuse scandal which was exposed by an investigative report broadcast on the UK BBC television programme ‘Panorama’ in 2011,61 and the model has recently begun to fall out of favour in the UK.62 The resulting “Transforming Care” programme committed the Department of Health to a rapid reduction in the number of people with IDD within inpatient care, particularly those who were perceived to have been detained for reasons of challenging behaviour.57 Concerns have been raised about the application of the principles of the Transforming Care programme to those in inpatient secure IDD services.6 Concerns include pressure being put on clinicians to discharge patients ‘as quickly as possible’, patients’ rehabilitation being hurried and/or truncated, patients being discharged before they are ready or without receiving community services being properly prepared to manage ongoing risks.6 The population in inpatient secure IDD services therefore represent a number of challenges to current UK government policy, and clarifications regarding their status is required.62

Following Involvement with the Criminal Justice System

The ultimate test of the efficacy of rehabilitation efforts made during involvement with the CJS is following release from prison, or discharge from an inpatient secure IDD service. Research examining the long-term outcomes of offenders with IDD in the UK after release or discharge is very limited. Yet, studies suggest that the clinical and forensic needs of people with IDD remain high, with high rates of poor housing options, poor mental health, a lack of engagement, offending behaviour, socio-economic deprivation, and, on occasion, victimisation in the community.6 There is a need for better care pathways and links between the CJS and community services, and such pathways can have a positive impact on outcomes for people with IDD.

Prison

The process of release from prison depends on the type of sentence, sentence length, behaviour in prison, and any time spent on remand.63 A prisoner serving a fixed-term (determinate) sentence is typically automatically released halfway through their sentence. If a prisoner’s sentence is 12 months or more, they are usually released on probation. Prisoners on an extended sentence, or a fixed-term sentence for 4 years or more, can apply for parole, which will be assessed by a parole board.63 An offender manager is employed by the probation service and is responsible for the offender throughout the whole of their sentence whether the sentence is served in custody, in the community or a mixture of both. The offender manager is responsible for assessing an offender’s risks and needs, planning their sentence and necessary interventions, and assessing how the offender progresses on their sentence, making any adjustments as required if circumstances change.64 All people serving community sentences or an indeterminate sentence of imprisonment for public protection, as well as the majority of offenders serving 12 months or more in custody, will have an offender manager. There is limited empirical focus on the utility of the probation service and offender managers for prisoners with IDD.64

Minimal research has evaluated the outcomes of people with IDD released from prison in the UK. However, due to the aforementioned difficulties, many people with IDD remain at risk of re-offending, as they are unable to access offending behaviour programmes in prison.6 One study traced 40 men who had been released from prison, reporting that the men were living in residences which varied widely in terms of level of restriction.65 The authors noted this did not seem to correlate with the seriousness of the offence, but factors such as the availability of community services.65 The men had limited engagement through employment or structured activity, minimal social networks, high levels of depression, anxiety, and alcohol/substance misuse, and high rates of re-arrest by the police.65 The authors concluded that the various services operated in ‘silos’, with the CJS (police, prison, and probation) not communicating with health teams, and health teams not communicating with social care. However, a number of areas of good practice exist, whereby prison and healthcare services have committed to joint working, and to the development of care pathways in order to improve outcomes for this disadvantaged group, as well as to adequately protect the public.66,67

Inpatient Secure IDD Services

The process of discharge planning for a patient from an inpatient secure IDD service typically begins early in their admission. Patients undergo a process of multidisciplinary assessment and observation, which should prescript their individualised care plan. At 6-month intervals, all professionals involved in the patient’s care meet to review progress and plan for the future; this is known as the care programme approach.68 Patients in the UK also have the right to a mental health review tribunal,69 which is an independent panel that reviews compulsory treatment orders for those subject to treatment under the Mental Health Act (1983). Applications for a mental health review tribunal are made by the patient or a close relative and the point at which an appeal can be made is dependent on the jurisdiction and admission status under which the patient is detained. Any patient who has not attended a tribunal within the past 3 years is automatically referred by the Secretary of State.70 Mental health review tribunals act as a safeguard to ensure that the continued detention of a patient under psychiatric care is not unlawful.69 The tribunal panel typically consists of a medical member, a tribunal judge, and a lay member, and has the power to uphold the detention of a patient in psychiatric hospital or to direct their discharge, either conditionally, in the case of restricted patients, or absolutely. No research has evaluated the outcome of tribunals for forensic inpatients with IDD, although this has been studied in forensic psychiatric patients without IDD. In the majority of cases, discharge is prompted by the care programme approach process, and linked to the everyday improvement and recovery of patients, as well as the availability of suitable community supervision, or placement options.13,14 A number of studies have evaluated the outcomes of patients within inpatient secure IDD services. One study reported that of 138 patients treated over a 6-year period, 77 were discharged and 61 were current inpatients. Of the 61 current patients, 36 were defined as ‘difficult to discharge long stay’ patients.10 The median length of stay for the discharged group was 2.8 years.10 About 90% of this group were discharged to lower levels of security, such as low secure services, or rehabilitation services.71 Further work on the long-stay cohort has identified that, despite significant time spent in secure services, institutional aggression and risk levels remain high.62 These patients represent a cohort of individuals who may present ongoing risks, who are progressing through their care pathway. Approximately one- third were discharged directly to community placements, under various legal conditions, such as guardianship or supervised discharge, or as an informal patient. Patients may also be discharged under a community treatment order.72,73 These arrangements depend on factors such as the patient’s section and their living situation upon discharge, but all broadly ensure a discharged patient adheres to certain conditions, such as attending outpatient treatment in the community, and is supervised by a competent relative or professional.72,73 Patients on all of these legal options have the ability to appeal through the mental health review tribunal at regular intervals.73

A recent systematic review of the outcome domains of relevance to inpatient secure IDD services identified 18 studies which examined formal reoffending (ie, formal charges and convictions) of patients discharged from inpatient secure IDD services at follow-up.13,14 Lindsay et al74 completed a 20-year follow-up study which evaluated the outcomes of 309 people from a 1986-to-2008 cohort of offenders referred to specialist inpatient secure IDD services, reporting that 16% of male sexual offenders, 43% of male nonsexual offenders, and 23% of female offenders committed at least one further offence. Alexander et al75 reported on 1182 patients discharged from four medium secure services between 1992 and 2001 in the UK, who committed serious/violent convictions at 1-, 2- and 5-year follow-up. Of those with intellectual disability (n = 145), 21 had been reconvicted at 5 years (total of 25 offences), and seven had committed a serious or violent offence at 2 years.75 Overall, this was lower than the comparison group (those diagnosed with personality disorder75); however, the authors noted these findings may need to be interpreted with caution, owing to the possibility that people with IDD were diverted away from the CJS and hence not subject to the same legal processes as others, or being subject to longer restrictions than other groups.75

Chester et al66 investigated the factors considered by clinicians involved in discharging patients from inpatient secure IDD services. The authors found that, although clinicians consider various factors relative to patient risk (to others /public protection, to the self, from others), they also consider risks to the organisation, i.e. reputational risks, as well as the ethical and legal risks of being risk averse, i.e. of unlawful detention.66 Clinicians were also found to consider various risk management factors, including legal frameworks and supervision requirements, the importance of a robust discharged plan that is holistic and personalised, and the need for multidisciplinary and multiagency working to ensure the discharge is a success.66

Summary

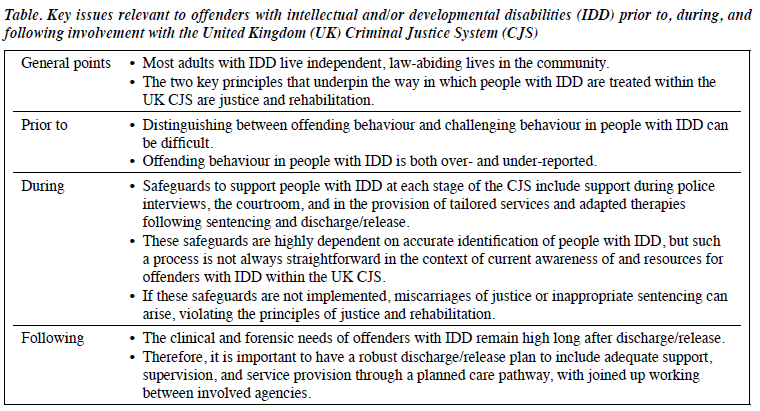

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the key issues of relevance to offenders with IDD prior to, during, and following involvement with the UK CJS.

Conclusions

Although thecareandmanagementofpeople with IDD within the CJS is comparatively advanced in the UK, the system is not perfect, and this paper highlights a number of strengths of the existing model, as well as ongoing challenges. Care of people with IDD is highly political, and many aspects of the model operate according to government policy, based upon charitable or independent reviews, rather than empirical research. It is clear that further research on offenders with IDD is urgently needed, to more fully understand the factors related to treatment outcomes. Preliminary work in this area has been completed in inpatient secure IDD services, and there is a need to continue it within community, hospital and prison settings. Ongoing attention and research regarding the way in which offenders with IDD are treated will ensure that these offenders, and their victims, are treated according to the principles of justice and rehabilitation.

Disclosure

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose. No financial support has been received for this paper.

References

- Kingdon A. Resettlement from secure learning disability In: Riding T, Swann C, Swann B, editors. The Handbook of Forensic Learning Disabilities. Radcliffe; 2005: 121-214.

- Bhaumik S, Tyrer F, Ganghadaran S. Assessing quality of life and mortality in adults with intellectual disability and complex health problems following move from a long-stay hospital. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 2011;8:183-90. Crossref

- HM Government. Law and the justice system. 2018. Available from: https://gov.uk/government/topics/law-and-the-justice-system. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Blackburn R. The Psychology of Criminal Conduct. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1993.

- Douglas KS, Hart SD, Webster CD, Belfrage H, Guy LS, Wilson CM, et al. Historical-Clinical-Risk Management-20, Version 3 (HCR-20V3): development and Int J Forensic Ment Health 2014;13:93-108. Crossref

- Taylor JL, McKinnon I, Thorpe I, Gillmer The impact of transforming care on the care and safety of patients with intellectual disabilities and forensic needs. BJPsych Bull 2017;41:205-8. Crossref

- Dale C, Moore Editorial. J Learn Disabil Offending Behav 2010;1:2-4. Crossref

- Clinical Research Group in Forensic Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Available from: http://www.forensiclearningdisability. com/. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Lindsay WR, Holland T, Wheeler JR, Carson D, O’Brien G, Taylor JL, et al. Pathways through services for offenders with intellectual disability: a one- and two-year follow-up Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2010;115:250-62. Crossref

- Alexander R, Hiremath A, Chester V, Green F, Gunaratna I, Hoare S. Evaluation of treatment outcomes from a medium secure unit for people with intellectual disability. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil 2011;5:22-32. Crossref

- Taylor JL, Thorne I, Robertson A, Avery Evaluation of a group intervention for convicted arsonists with mild and borderline intellectual disabilities. Crim Behav Ment Health 2002;12:282-93. Crossref

- Langdon PE, Murphy GH, Clare IC, Palmer EJ, Rees An evaluation of the EQUIP treatment programme with men who have intellectual or other developmental disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2013;26:167-80. Crossref

- Morrissey C, Langdon PE, Geach N, Chester V, Ferriter M, Lindsay WR, et al. A systematic review and synthesis of outcome domains for use within forensic services for people with intellectual disabilities. BJPsych Open 2017;3:41-56. Crossref

- Morrissey C, Geach N, Alexander R, Chester V, Devapriam J, Duggan C, et al. Researching outcomes from forensic services for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities: a systematic review, evidence synthesis and expert and patient/carer consultation. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2017.

- Department of Health. The Bradley Report: Lord Bradley’s review of people with mental health problems or learning disabilities in the criminal justice system. London; 2009.

- Talbot J. No One Knows: offenders with learning disabilities and learning difficulties. Int J Prison Health 2009;5:141-52. Crossref

- Durcan G, Saunders A, Gadsby B, Hazard A. The Bradley report five years on: an independent review of progress to date and priorities for further developments. 2014.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists, British Psychological Society, Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. Challenging Behaviour: A Unified Approach (CR144). London; 2007.

- Douds F, Bantwal A. The “forensicisation” of challenging behaviour: the perils of people with learning disabilities and severe challenging behaviours being viewed as “forensic” patients. J Learn Disabil Offending Behav 2011;2:110-3. Crossref

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Forensic care pathways for adults with intellectual disability involved with the criminal justice system. London; 2014.

- Lyall R, Kelly M. Specialist psychiatric beds for people with learning disability. Psychiatr Bull 2007;31:297-300. Crossref

- Devapriam J, Alexander Tiered model of learning disability forensic service provision. J Learn Disabil Offending Behav 2012;3:175-85. Crossref

- Alexander RT, Chester V, Green FN, Gunaratna I, Hoare Arson or fire setting in offenders with intellectual disability: clinical characteristics, forensic histories, and treatment outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2015;40:189-97. Crossref

- Archer N, Hurley A justice system failing the autistic community. J Intellect Disabil Offending Behav 2013;4:53-9. Crossref

- Home Police and Criminal Evidence Act. London; 1985.

- Home Office. Revised Code of Practice for the detention, treatment and questioning of persons by Police Officers. London; 2017.

- Clare IC, Gudjonsson The vulnerability of suspects with intellectual disabilities during police interviews: a review and experimental study of decision-making. Ment Handicap Res 1995;8:110-28. Crossref

- Gudjonsson GH, Clare IC, Cross The revised PACE “Notice to Detained Persons”: how easy is it to understand? J Forensic Sci Soc 1992;32:289-99. Crossref

- O’Mahony BM. The emerging role of the Registered Intermediary with the vulnerable witness and offender: facilitating communication with the police and members of the judiciary. Br J Learn Disabil 2010;38:232-7. Crossref

- Gudjonsson GH. The relationship of intelligence and memory to interrogative suggestibility: the importance of range effects. Br J Clin Psychol 1988;27:185-7. Crossref

- Gudjonsson GH, Clare IC. The relationship between confabulation and intellectual ability, memory, interrogative suggestibility and acquiescence. Pers Individ Dif 1995;19:333-8. Crossref

- North AS, Russell AJ, Gudjonsson GH. High functioning autism spectrum disorders: an investigation of psychological vulnerabilities during interrogative interview. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol 2008;19:323-34. Crossref

- Jessiman T, Cameron The role of the appropriate adult in supporting vulnerable adults in custody: comparing the perspectives of service users and service providers. Br J Learn Disabil 2017;45:246-52. Crossref

- Medford S, Gudjonsson GH, Pearse J. The efficacy of the appropriate adult safeguard during police interviewing. Legal Criminol Psychol 2003;8:253-66. Crossref

- Leggett J, Goodman W, Dinani S. People with learning disabilities’ experiences of being interviewed by the police. Br J Learn Disabil 2007;35:168-73. Crossref

- Smith T, Polloway EA, Patton JR, Beyer Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the criminal justice system and implications for transition planning. Educ Train Dev Disabil 2008;43:421-30.

- Boer H, Alexander R, Devapriam J, Torales J, Ng R, Castaldelli- Maia J, et al. Prisoner mental health care for people with intellectual disability. Int J Cult Ment Health 2016;9:442–6. Crossref

- McKinnon I, Thorp J, Grubin D. Improving the detection of detainees with suspected intellectual disability in police custody. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil 2015;9:174-85. Crossref

- Rogers TP, Blackwood NJ, Farnham F, Pickup GJ, Watts Fitness to plead and competence to stand trial: a systematic review of the constructs and their application. J Forensic Psychiatry Psychol 2008;19:576-96. Crossref

- Taylor Fitness to plead and stand trial: the impact of mild intellectual disability. Doctoral thesis (University College London). 2011.

- Mental Health Act 1983. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/legal-rights/community-treatment-orders-ctos/. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Baroff GS, Gunn M, Hayes S. Legal issues. In: Lindsay WR, Taylor JL, Sturmey P, Offenders with Developmental Disabilities. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. Crossref

- Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1999/23/contents. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Coroner’s and Justice Bill (2008-9). Available from: https://www.uk/documents/lords-library/hllcoroners-justice.pdf. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- O’Mahony BM. Accused of murder: supporting the communication needs of a vulnerable defendant at court and at the police station. J Learn Disabil Offending Behav 2012;3:77-84. Crossref

- HM Government. Criminal Justice Act 2003. London; 2003.

- Ali A, Ghosh S, Strydom A, Hassiotis A. Prisoners with intellectual disabilities and detention status. Findings from a UK cross sectional study of prisons. Res Dev Disabil 2016;53-54:189-97. Crossref

- Esan F, Chester V, Gunaratna IJ, Hoare S, Alexander The clinical, forensic and treatment outcome factors of patients with autism spectrum disorder treated in a forensic intellectual disability service. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2015;28:193-200. Crossref

- Murphy GH, Gardner J, Freeman MJ. Screening prisoners for intellectual disabilities in three English prisons. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2017;30:198-204. Crossref

- Hayes S, Shackell P, Mottram P, Lancaster R. The prevalence of intellectual disability in a major UK prison. Br J Learn Disabil 2007;35:162-7. Crossref

- McKenzie K, Michie A, Murray A, Hales C. Screening for offenders with an intellectual disability: the validity of the Learning Disability Screening Questionnaire. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33:791-5. Crossref

- Silva D, Gough K, Weeks Screening for learning disabilities in the criminal justice system: a review of existing measures for use within liaison and diversion services. J Intellect Disabil Offending Behav 2015;6:33-43. Crossref

- Ashworth S. Autism is underdiagnosed in prisoners. BMJ 2016;353:i3028. Crossref

- Talbot J. Prisoners’ voices: experiences of the criminal justice system by prisoners with learning disabilities. Tizard Learn Disabil Rev 2010;15:33-41. Crossref

- Fazel S, Xenitidis K, Powell J. The prevalence of intellectual disabilities among 12,000 prisoners: a systematic review. Int J Law Psychiatry 2008;31:369-73. Crossref

- Department of Health. Review of health and social services for mentally disordered offenders and others requiring similar services. London: HM Stationery Office;

- Alexander R, Devapriam J, Michael D, McCarthy J, Chester V, Rai R, et al. Why can’t they be in the community? A policy and practice analysis of transforming care for offenders with intellectual disability. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil 2015;9:139-48. Crossref

- Alexander R, Crouch K, Halstead S, Piachaud J. Long-term outcome from a medium secure service for people with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 2006;50:305-15. Crossref

- Hollins Developmental psychiatry: insights from learning disability. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:201-6. Crossref

- Large J, Thomas C. Redesigning and evaluating an adapted sex offender treatment programme for offenders with an intellectual disability in a secure setting: preliminary findings. J Learn Disabil Offending Behav 2011;2:72-83. Crossref

- BBC One (2011), “Undercover care: the abuse exposed”, Panorama, available at: bbc.co.uk/programmes/b011pwt6 Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Chester V, Vollm B, Tromans S, Kapugama C, Alexander Long- stay patients with and without intellectual disability in forensic psychiatric settings: comparison of characteristics and needs. BJPsych Open 2018;4:226-34. Crossref

- HM Government. Leaving Prison. Available from: https://www.gov. uk/leaving-prison/print. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Offender Managers Helpline. Offender Managers. Available from: https://offendersfamilieshelpline.org/index.php/offender-managers/. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Murphy GH, Chiu P, Triantafyllopoulou P, Barnoux M, Blake E, Cooke J, et Offenders with intellectual disabilities in prison: what happens when they leave? J Intellect Disabil Res 2017;61:957-68. Crossref

- Chester V, Brown AS, Devapriam J, Axby S, Hargreaves C, Shankar R.Discharging inpatients with intellectual disability from secure to community services: risk assessment and management considerations. Adv Ment Heal Intellect Disabil 2017;11:98-109. Crossref

- Benton C, Roy The first three years of a community forensic service for people with a learning disability. Br J Forensic Pract 2006;10:4-12. Crossref

- Selby G, Alexander Care programme approach in a forensic learning disability service. Br J Forensic Pract 2004;6:26-31. Crossref

- Jewell A, Dean K, Fahy T, Cullen AE. Predictors of Mental Health Review Tribunal (MHRT) outcome in a forensic inpatient population: a prospective cohort BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:25. Crossref

- Thom K, Nakarada-Kordic I. Mental Health Review Tribunals in action: a systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychiatry Psychol Law 2014;21:112-26. Crossref

- Devapriam J, Fosker H, Chester V, Gangadharan S, Hiremath A, Alexander Characteristics and outcomes of patients with intellectual disability admitted to a specialist inpatient rehabilitation service. J Intellect Disabil 2018:1744629518756698. Crossref

- Community treatment orders. 2018.

- Sectioning and guardianships. Available from: https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/legal-rights/community-treatment-orders-ctos/#.WuhUKa6nHIU. Accessed 1st March 2018.

- Lindsay WR, Steptoe L, Wallace L, Haut F, Brewster An evaluation and 20-year follow-up of a community forensic intellectual disability service. Crim Behav Ment Health 2013;23:138-49. Crossref

- Alexander RT, Chester V, Gray NS, Snowden RJ. Patients with personality disorders and intellectual disability – closer to personality disorders or intellectual disability? A three-way comparison. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2012;23:435-51. Crossref