East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:134-8 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1829

THEME PAPER

Dr Kavin Kit-wan Chow, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital

Dr Oliver Chan, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital Dr Mandy Wai-man Yu, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Dr Cola Siu-lin Lo, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital Dr Dorothy Yuen-yee Tang, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital

Dr Dickson Lai-yin Chow, Shatin Hospital

Dr Bonnie Wei-man Siu, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital

Dr Eric Fuk-chi Cheung, Kwong Wah Hospital

Address for correspondence: Dr Kavin Kit-wan Chow, Associate Consultant Psychiatrist, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong.

Email: ckw338@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 29 March 2018; Accepted: 3 August 2018

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to validate the Correctional Mental Health Screen (CMHS) in the Hong Kong prison population and determine the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among remand prisoners in Hong Kong and the associated factors of mental illness.

Methods: This cohort study was conducted at the Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre and the Tai Lam Centre for Women in Hong Kong. Remand prisoners aged ≥21 years were recruited between May and August 2014. Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected. Each remand prisoner was assessed using the appropriate CMHS for males or for females, then interviewed by a specialist psychiatrist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV for current affective disorder and psychotic disorder for cross- validation.

Results: A total of 245 remand prisoners were recruited (150 males and 95 females; mean age, 25.8 years). Of them, 51% (55% males and 44% females) had a lifetime history of psychiatric disorder, whereas 39.6% (46% males and 29.5% females) had a current psychiatric disorder. The most common psychiatric disorder was substance use disorder (>36%), followed by mood disorder (>20%), psychotic disorder (5.3%), and lifetime neurotic disorder (3.7%). Living in a public housing estate (odds ratio [OR] = 1.99), a history of childhood conduct problem (OR = 2.40), and a forensic history (OR = 1.97) were associated with an increased risk of having a psychiatric disorder. The CMHS had good diagnostic efficiency after cross-validation with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Conclusion: Psychiatric disorders are prevalent in remand prisoners in Hong Kong. The CMHS is an effective tool to screen remand prisoners for timely treatment of prisoners with mental health needs.

Key words: Mental disorders; Prisoners

Introduction

Mental health problems cause morbidities in the prison population.1-3 The prevalence of mental disorder in prisoners is significantly higher than that in the general population.4-6 In two large-scale studies of psychiatric morbidity among prisoners in England and Wales, 37% of sentenced males, 63% of remanded males, 57% of sentenced females, and 76% of remanded females had a mental disorder.7,8 In a systematic review of 63 surveys involving 22,790 inmates in 12 countries, psychotic illness, major depression, and personality disorder are found in 3.7%, 10%, and 65% of male inmates, and 4%, 12%, and 42% of female inmates, respectively.5

In the United States, a national survey reported that 83% of 1760 jails provide some form of initial screening for mental health treatment needs,9 but the procedures were highly variable. Although screening measures that assess both mental competence and the attitudes or personality characteristics that may lead to disciplinary problem (especially risk of violence) have been developed for correctional populations, psychiatric screening measures for psychiatric disorders are scarce. The 14-item Referral Decision Scale was designed to identify mood or psychotic

disorders; it has moderate sensitivity and negative predictive power but low specificity and positive predictive power among male prison and jail detainees.10-12 The Correctional Mental Health Screen (CMHS)13 was designed to address the limitations of existing mental health screening for jail detainees. An eight-item version for females (CMHS-F)13 and a 12-item version for males (CMHS-M)14 were derived from a set of screening instruments to detect clinically significant mental health problems among incarcerated adults.

In Hong Kong, the population of prisoners (both remand and sentenced) ranged from 10,000 to 13,000 from 2001 to 2009, with the rate of prison population being 140 to 185 per 100,000 population, which is at the mid-point among countries.15 Nonetheless, the prevalence of mental illness among prisoners is not known. An efficient screening procedure for mental health problems is pertinent to lessen the burden of correctional staff in managing disturbed prisoners. This study aimed to validate the CMHS in the Hong Kong prison population and determine the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among remand prisoners in Hong Kong and the associated factors of mental illness.

Methods

This cohort study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the New Territories West Cluster of the Hospital Authority. It was conducted at the Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre and the Tai Lam Centre for Women in Hong Kong (these two centres accommodate for >90% of remand prisoners). Remand prisoners aged ≥21 years were recruited between May and August 2014. Those who refused to participate, were unable to understand Chinese or English, or were unfit to give consent were excluded.

The CMHS-M and CMHS-F were translated to Chinese using the Brislin’s method of translation and back-translation. The English versions were first forward- translated to Chinese by three independent translators. The consensual version was then independently back-translated to English by another three translators. The consensual backward translation was compared with the original version for any translation errors.

Sociodemographic and clinical data of remand prisoners were collected. Each remand prisoner was assessed using the CMHS-M or CMHS-F and then interviewed by a specialist psychiatrist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV for current affective disorder and psychotic disorder for cross-validation.

The receiver operating characteristics curve was used to evaluate the discriminative capacity of CMHS for psychiatric disorders. Sensitivity, specificity, and the area under the curve (AUC) were cross-validated using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Logistic regression analysis of backward stepwise procedure model

was used to determine the factors associated with psychiatric disorder. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Windows version 23; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US).

Results

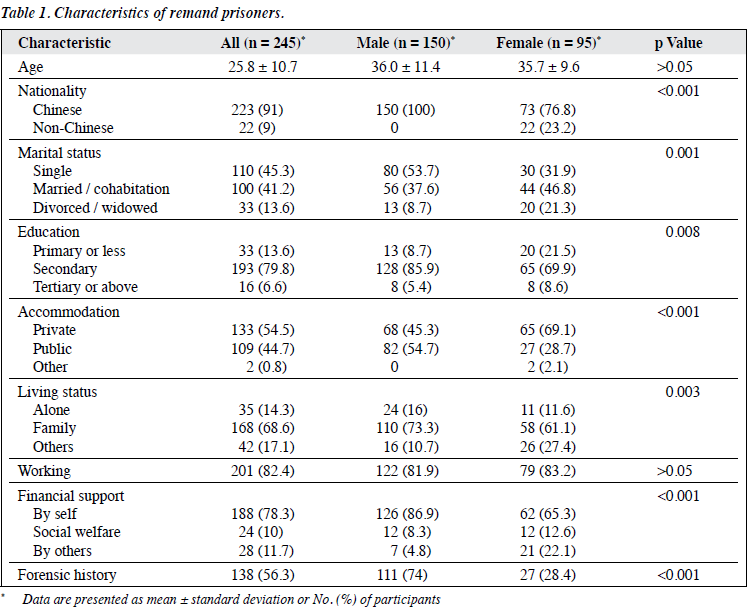

A total of 245 remand prisoners were recruited (150 males and 95 females; mean age, 25.8 years) [Table 1]. The response rate was 84%; 47 were excluded mainly because of language barriers. Approximately 9% of the remand prisoners were charged with a violent offence, including assault, wounding, or criminal damage.

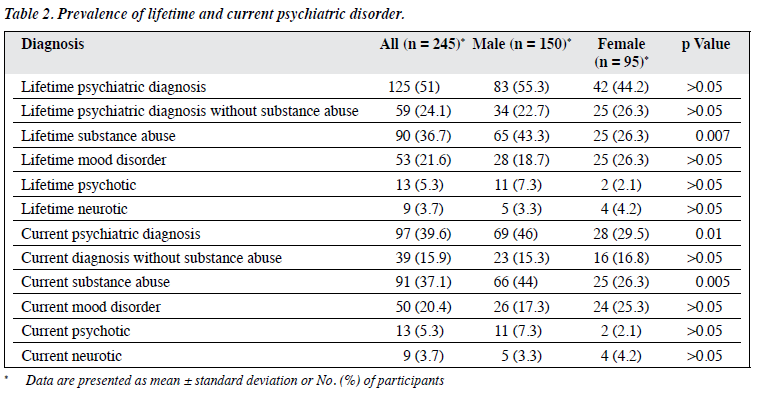

Of the 245 remand prisoners, 51% (55% males and 44% females) had a lifetime history of psychiatric disorder, whereas 39.6% (46% males and 29.5% females) had a current psychiatric disorder (Table 2). The most common psychiatric disorder was substance use disorder (>36%), followed by mood disorder (>20%), psychotic disorder (5.3%), and lifetime neurotic disorder (3.7%). The prevalence of lifetime substance use disorder was higher in male than in female (43.3% vs 26.3%, χ2 = 7.248, p = 0.007). The most common drugs of abuse were methamphetamine (8.2%) and ketamine (7.8%); benzodiazepine, alcohol, and cough mixture were also used. About 8% of remand prisoners used more than two types of drug at the same time.

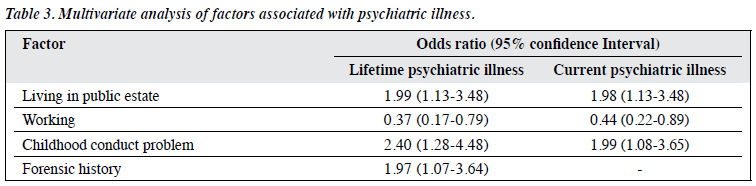

Remand prisoners with and without lifetime psychiatric disorder were compared using multivariate analyses. Living in a public housing estate (odds ratio [OR] = 1.99, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.13-3.48), a history of childhood conduct problem (OR = 2.40, 95% CI = 1.28- 4.48), and a forensic history (OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.07- 3.64) were associated with an increased risk of having a psychiatric disorder (Table 3).

Internal consistency of the CMHS-M and CMHS-F was good, with Cronbach’s α being 0.75 and 0.83, respectively. The CMHS had good diagnostic efficiency after cross-validation with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. For lifetime psychotic disorder, the AUC was

0.80 for CMHS-M and 0.86 for CMHS-F. Using a CMHS cut-off score of >2 (half of full score), the sensitivity and specificity were 96.2% and 41.1% for CMHS-M, and 87.5% and 77.5% for the CMHS-F. For current psychotic disorder, the AUC was 0.84 for CMHS-M and 0.90 for CMHS-F. Using a CMHS cut-off score of 2 (half of full score), the sensitivity and specificity were 90.9% and 36.7% for CHMS-M, and 100% and 62.4% for CMHS-F.

Discussion

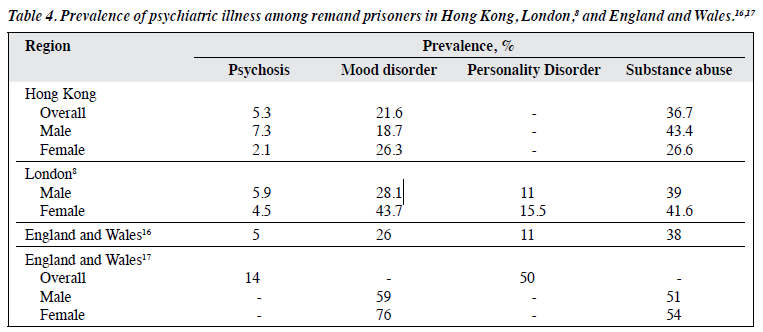

Our study was the first to investigate the prevalence of mental illness among remand prisoners in Hong Kong. The prevalence of psychosis, mood disorder, and substance abuse disorder among remand prisoners in Hong Kong was comparable to those in England and Wales16,17 (Table 4). The prevalence of psychiatric disorders was higher among remand prisoners than among the general population and sentenced prisoners. Remand prisoners have to adjust to the prison environment after the shock of incarceration, stress from sudden or unexpected separation with their normal life and family, and stress from the ongoing litigation with uncertainties about the sentence. In addition, withdrawal from drugs or discontinuation of psychiatric medications could precipitate the relapse of mental problems. Thus, there is a need for screening and early intervention for remand prisoners with treatable psychiatric disorders. The CMHS can be applied by the correctional staff to screen prisoners for possible psychiatric disorders at different stages of remand, so that timely referral to psychiatric professionals for assessment can be made. With early identification of psychiatric problems, timely treatment could be provided to alleviate psychological distress of prisoners. This can also help to reduce the rates of suicide, violence, substance- related death, and recidivism, and can potentially lessen the work stress of correctional staff.

One limitation of this study was the limited sample size, and not all remand prisoners were interviewed. Those with urgent psychiatric needs might have already been sent to psychiatric hospital for treatment or to the Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre for psychiatric reports. Those with known psychiatric disorders or acute psychiatric conditions might have been excluded. However, the sample was representative of the remand population. In addition, inter- rater reliability and test-retest reliability of CHMS were not evaluated because remand prisoners usually stay in prison temporarily; they may be released on bail or sentenced to other prisons within a short period. Further, CHMS has low specificity and positive predictive value, despite high sensitivity, for current affective disorder and psychotic disorder. Studies with a larger sample is warranted to determine the cut-off scores and the specificity and positive predictive values of CHMS for current affective and psychotic disorder.

Conclusion

Psychiatric disorders are prevalent in remand prisoners in Hong Kong. The CMHS is an effective tool to screen remand prisoners for timely treatment of prisoners with mental health needs.

Acknowledgement

We thank the staff of the Correctional Services Department for their assistance in the logistics.

References

- Taylor PJ, Gunn J. Violence and psychosis. I. Risk of violence among psychotic men. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1945-9. Crossref

- Coid Mentally abnormal prisoners on remand: rejected or accepted by the NHS? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:1779-82. Crossref

- Davidson M, Humphreys MS, Johnstone EC, Owens DG. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among remand prisoners in Scotland. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:545-8. Crossref

- Brink JH, Doherty D, Boer A. Mental disorder in federal offenders: a Canadian prevalence Int J Law Psychiatry 2001;24:339-56. Crossref

- Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 2002;359:545-50. Crossref

- Fazel S, Seewald K. Severe mental illness in 33,588 prisoners worldwide: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2012;200:364-73. Crossref

- Gunn J, Maden A, Swinton M. Treatment needs of prisoners with psychiatric disorders. BMJ 1991;303:338-41. Crossref

- Maden A, Taylor CJA, Brooke D, Gunn Mental Disorder in Remand Prisoners. London: Home Office; 1995.

- Steadman H, Veysey Providing services for jail inmates with mental disorder. Research in Brief. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 1997.

- Ford JD, Trestman RL, Wiesbrock VH, Zhang Validation of a brief screening instrument for identifying psychiatric disorders among newly incarcerated adults. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:842-6. Crossref

- Teplin LA, Swartz J. Screening for severe mental disorder in jails: the development of the referral decision scale. Law Hum Behav 1989;13:1-18. Crossref

- Veysey BM, Steadman HJ, Morrissey JP, Johnsen M, Beckstead Using the Referral Decision Scale to screen mentally ill jail detainees: validity and implementation issues. Law Hum Behav 1998;22:205-15. Crossref

- Ford JD, Trestman RL, Wiesbrock V, Zhang Development and validation of a brief mental health screening instrument for newly incarcerated adults. Assessment 2007;14:279-99. Crossref

- Zimmerman M, Mattia A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58:787-94. Crossref

- Walmsley R. World Prison Population List. 10th ed. The International Centre for Prison Studies; 2014.

- Brooke D, Taylor C, Gunn J, Maden A. Point prevalence of mental disorder in unconvicted male prisoners in England and BMJ 1996;313:1524-7. Crossref

- Office for National Statistics. ONS Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity among Prisoners in England and Wales, Available form: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-4320-1. Accessed 1 Jan 2017.