Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2000;10(4):22-24

REVIEW ARTICLES

ADULT LEARNING DISABILITY PSYCHIATRY SERVICES: LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION OF NATIONAL GUIDELINES

G O’Brien, J Radley, J Joyce

Dr G O’Brien, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Dr J Radley, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Dr J Joyce, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Address for correspondence:Dr G O’Brien Consultant Psychiatrist Northgate Hospital Morpeth Northumberland UK

ABSTRACT

People with learning disability have high rates of psychiatric disorder. Unlike disorders presenting in the general population, these problems are unfamiliar to many general psychiatrists. In the UK, specialist services have evolved to meet this need. These services are described, in terms of types of service, bed numbers, manpower, organisation, and educational function.

Key words: Adult Services; Learning Disability; Psychiatric Disorder

INTRODUCTION

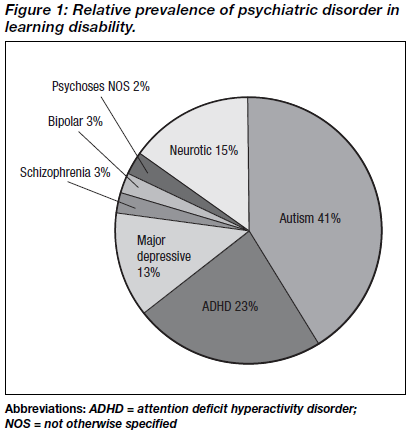

Specialist psychiatric services for adults with learning disability are a high profile element of the UK mental health service. These services have a long history as reviewed by Perini in this issue.1 Essentially, the institutional era of the first three- quarters of the 20th century has been succeeded by the wholesale implementation of community residential care in recent years. In turn, the experience of professionals and families who are charged with the community care of adults with learning disabilities has clarified the extent of psycho- pathology among this high profile population. It is now accepted that some 50% of all adults with learning disability have a significant psychiatric or behavioural problem at any one time.2 These problems have a pattern of their own, and they are not always classifiable within conventional diagnos- tic systems, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Diseases (DSM)-IV and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10. Also, due to the intellectual and developmental disabilities, psychiatric and behavioural problems that occur among adults with learning disabilities show major differences in types from those of the general population.3-5 Notably, autism and attention deficit hyperactive disorder are more common among adults with learning disability (Figure 1), and the symptoms presenting in other major disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression, have a profile of their own among people with learning disability. These two empirical observations are crucial. Psychiatric disorder is common among people with learning disability, and the problems presenting are unfamiliar to general psychiatrists. The psychiatry of learning disability is therefore one of the range of psychiatric specialities of the National Health Service in the UK, a situation which is being increasingly mirrored in other countries.

Figure 1 shows the principal psychiatric diagnosis in a community-based group of 78 young adults (aged 18 to 22 years) with learning disability (severe — intelligence quotient [IQ] < 35, n = 21; moderate — IQ 35 to 49, n = 16; mild — IQ 50 to 69, n= 57) who also had psychiatric disorder, expressed as a percentage proportion of the sample. Major depression, anxiety neurosis, and major psychoses are all more common than in the general population, but autism and attention deficit disorder are the most common psychiatric disorders encountered.

In recent years, efforts have been made to arrive at some consensus concerning the nature and design of specialist psychiatric services for people with learning disability. Close attention has been given to the role of inpatient services, and to bed numbers. Here, the first principal, and the most important, is that the prime responsibility for residential care of people with learning disabilities lies with Social Services, who also provide day care and have responsibilities in the areas of ongoing adult education and leisure. It is the National Health Service’s responsibility to provide residential and inpatient care for those whose mental health needs require a specialist service. Inpatient psychiatric services for people with learning disabilities have developed according to clinical needs. Consequently, these specialist inpatient services fulfil three roles: assessment, acute treatment, and long-term care.

NATIONAL EXPERIENCE AND LOCAL SERVICES

Assessment inpatient services are typically small, and locally based. A health district of around 200,000 to 300,000 people often has something of the order of two beds for this purpose. Given that most assessment takes place in the individual’s home and daytime environment, only those who are posing a difficult problem for assessment are admitted to these facilities. Common clinical examples include cases in which extreme disruptive behaviour figure highly; other cases may feature marked social withdrawal and/or a sudden loss of adaptive skills. Often, this service is based in the same setting/ inpatient unit as the acute treatment beds. As assessment and acute treatment are so closely related as functions, such an arrangement has much to offer. The clinical problems addressed by the two services have much in common. The acute treatment services often operate most effectively when dealing with mental illness and exacerbations of neuro- psychiatric or pervasive developmental disorders. In some services, these inpatient units also serve a respite care function, typically for families caring for individuals with longstanding, refractory severe behaviour disorders. Regarding numbers of beds required for short stay (combining assessment, acute treatment, and short-term respite together), there is a reason- able degree of consensus. Writing in 1989, Menolascino6 recommended the provision of between 16 and 40 beds per million of the general population. In keeping with this, a recent UK survey7 found that British services at present are typically operating at 20 beds per million. At the level of a health district, with a typical population of 200,000 to 300,000, these beds operate together with the assessment beds cited above, often in houses of two to four beds, giving a short-stay inpatient service of 6 to 8 beds. For example, the Northgate Hospital inpatient acute psychiatry unit, which serves around one million of the general population, has 25 beds. Not only does this arrangement carry economies of scale, it also enables the development of expertise in the field.

The role of the National Health Service in long-term inpatient care has been, and still is, more controversial. Given that there is a clear consensus that ongoing residential care — including associated day care, leisure, and ongoing education — is a social services function, there is no clear consensus as to what role the National Health Service should take here. Indeed, some say there is no role for the National Health Service in such long-term care. However, faced with the widespread severe psychiatric and behavioural problems of this population, and their developmental and other immediate nursing needs (notably continence, mobility, communication, and profound skills deficits), most health services in the UK do take responsibility for some specialist long-term care of adults with learning disabilities. This is most often for cases where all the agencies involved agree that the challenges posed by the individual’s ongoing care are primarily health-related. In fact, although such cases comprise a small minority of the total population of those with learning disability, a recent UK survey found that the number of beds in such services is currently just over 100 per million of the general population. Interestingly, while the number of acute/short- stay beds recommended for specialist learning disability services has been constant for some time, this recent finding represents a substantial reduction on earlier recommendations of bed numbers. For example according to Day,2 200 to 300 beds per million were previously estimated to be required. This reduction, therefore, is a reflection of the greater role taken on by social services in recent years. The fact that most district health services retain a smaller, but still substantial, complement of inpatient beds for the ongoing care of learning disabled individuals with enduring mental health and severe developmental problems is important. In tur n, such a pragmatic approach is a reflection of the severity of the challenges presented by this group. As with short-stay beds, practice varies between centres in the UK. Most choose to keep services as local as possible, in small Health District units (serving 200,000 to 300,000 of the general population). Others prefer to operate from larger centres of greater critical mass, often including academic programmes of multidis- ciplinary teaching, service evaluation, and research as part of their remit.

While inpatient care is the most staff-intensive, and consequently the most expensive, element of a specialist learning disability service, most clinical work in this area is carried out on a community basis. Community teams offering pro-active support and domiciliary-based interventions, outpatient work, and a range of specialist home and day-care based therapists form the bedrock of the service. Mutual support and enhancement of therapists’ skills, through training and the development of the service evidence base, are fundamental. Recently, the maintenance of more difficult cases in the community has been advocated by energetic and pro- active community work through policies of so-called ‘aggressive outreach. Such work is only possible where close collaboration between involved agencies is the nor m.8

Consequently, one particularly effective method of service delivery features inpatient and community services working not just in partnership, but as an integrated specialist service; some of the most successful examples of this include a com- munity team based in the same unit as the inpatient service.9

A good consensus exists on the staffing required for such community work. The Royal College of Psychiatrists10 has calculated that there should be one consultant psychiatrist per 100,000 of the general population. Perhaps not surprisingly, there is often a shortfall in practice, and currently one per 250,000 is nearer to the norm.11 Interestingly, this amounts to one consultant to each health district of around 200,000 to 300,000 people. Given that most health districts operate a community learning disability team, the arrangement has some coherence, with one consultant psychiatrist working with each team, usually with a psychiatric trainee on a rotational attachment. Teams operating in these district services for a population of 200,000 to 300,000 people typically comprise: community nurses (6 to 7 full-time staff), clinical psychologists (2), occupational therapists (1 to 2), speech therapists (1 to 2), physiotherapist (1).11 Part-time sessional input from other specialities such as dietetics and other therapists is also common. Finally, many such teams include active inter-agency collaboration, being integrated with local authority teams of social workers, offering a comprehensive team for the community care of people with learning disability.

CONCLUSION

In the UK, experience of meeting the psychiatric needs of people with learning disability in the post-institutional era has resulted in the development of a network of local integrated services, consisting of specialist inpatient units in partnership with community learning disability teams. In areas of high population density, larger inpatient units take on these functions, with good opportunities for maintenance and development of expertise, and other academic activities, in addition to the inherent attractions of economies of scale.

REFERENCES

- Perini AF. Development of health service policy for people with learning disability in the United Kingdom. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2000;10(4):18-21.

- Day KA. Mental health services for people with mental retardation: a framework for the future. J Intellect Dis Res 1993;37 (Suppl. 1): 7-16.

- Gillberg C, Persson E, Grufman M, Themner U. Psychiatric disorders in mildly and severely retarded urban children and adolescents: epidemiological aspects. Br J Psychiatry 1986; 149:68-74.

- O’Brien G. The adult outcome of child lear ning disability [dissertation]. University of Aberdeen; 1998.

- O’Brien G. Learning disability. In: Gillberg C, O’Brien G, eds. Developmental disability and behaviour. Clin Develop Med 2000;149:12-26.

- Menolascino FJ. Model services for treatment/management of the mentally retarded mentally ill. Community Health J 1989;25: 145-155.

- Bailey NM, Cooper SA. NHS beds for people with learning disabilities. Psychiatr Bull 1998;22:69-72.

- Department of Health. The new NHS. Modern. Dependable. London: The Stationary Office; 1997. Report No.: Cmnd 3807.

- O’Brien G. Current patterns of service provision for the psychiatric needs of mentally handicapped people. Psychiatr Bull 1990;14: 6-7.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Mental health of the nation: the contribution of psychiatry. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 1992.

- Bailey NM, Cooper SA. Psychiatrists and the learning disabilities health service. Psychiatr Bull 1998;22:25-28.

Dr G O’Brien, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Dr J Radley, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Dr J Joyce, Consultant Psychiatrist, Northgate Hospital, Morpeth, Northumberland.

Address for correspondence: Dr G O’Brien

Consultant Psychiatrist

Northgate Hospital

Morpeth Northumberland

UK