Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry (1996) 6 (1), 30-37

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Summary

Among many causes of offending and re-offending, there is a proposal that a person might commit crime as a way of coping with life hardship and maladaptive coping behaviour might be a pre-condition for recidivism. Retraining and remedial education as measures of rehabilitation can be feasible and valuable ways of preventing crime. More study in this direction is indicated and should be fruitful. The present study showed that ex-offenders employ a wide range of coping strategies, but recourse to substances, in particular tobacco, was almost always made in presence of hardship. There was an association between the type of strategies used and demographic characteristics.

Keywords: coping strategies, life hardships, ex-offenders

INTRODUCTION

Ex-offenders, like other people, have individual physi cal , emotional , social , and intellectual needs; also they have different personal bases of knowledge, skills, experi ences, and attitudes. Some ex-offenders will later reach f ull independence in life, while others may never be able to do so. Most would agree that there is a strong relation ship between lack of adjustment in the community and recidivism. It stands to good reasoning that individuals successful in psychosocial adjustment are less apt to be involved in antisocial or unlawful activity. This requires not only the availability of a friendly and congenial envir onment, but also the appropriate social, life and other kinds of skills to maintain the homeostasis in the person environment interface.

To change their actions so that the ex-offenders become less vulnerable to temptations and less inclined towards criminal activities, it will be necessary to modify the cognitive templates or alter the coping strategies they use to perceive, respond, and meet the environmental demands. To understand these mediated processes, it seems most fruitful to examine the behaviour patterns of the ex-offenders and the mental mechanisms that accom pany them, especially in the presence of stress originating from life hardship.

Toch (1977) theorizes that most violent episodes can be traced to well-learned, systematic strategies of physical aggression that some people have found effective in coping with difficulties, particularly conflictual, impersonal relationships. Thus, violence is not simply the act of a person acting on impulse; it is the act of one who has habitual response patterns of reacting violently in particular situations. There is a suggestion that, if we examine the history of violent persons, we will discover surprising consistency in their coping responses to frus trations in life. A threat to the self-esteem, well-being or valued possessions of the person who has few coping skills for solving problems or resolving disputes and con flicts may facilitate or even precipitate violence. This is especially true if the person's subculture advocates that disputes can be settled through physical aggression. People who are convinced that aggression or the like is the best strategy for achieving success or just ensuring survival may thereby hold the erroneous belief that self advantage at the expense of others is the correct course of action to take.

In a similar vein, Berkowitz (1970) hypothesizes that people sometimes react violently, not because they anticipate pleasure or displeasure from their actions, but because "situational stimuli have evoked the response they are predisposed or set to make that setting".

Whether perpetuation of criminal behaviour has a bearing with the coping abilities has never been verified in a scientific research. Much of the focus so far in the studies ever undertaken on offenders has been on their off ending behaviour per se and its association with social or sociological, psychological and cultural attributes of the offenders. Several behavioural and social scientists (e.g. ,Goldstein, 1975; Gibbons, 1977; Petersen, 1977) contend that criminality in many cases may simply reflects being in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people.

It is possible that the 'taken-for-granted' assumptions and common-sense boundaries which apparently every one establishes to make life manageable are breached in some of these offenders. Not only is the existence of cognitive and material resources available to an ex offender called into question, but oftentimes in reality, daily life needs to be re-negotiated each day. Managing money, keeping personal hygiene, and conducting a job search are all skills most people take for granted. How ever, for those previously committed to a drug or criminal lifestyle, the prospect of having to balance his expenses against remuneration or secure a domicile can be genu inely frightening. Probably it is ripe time to embark on a fundamental re-thinking of this real-life issue.

The present study is the first original one of its kind ever undertaken in the population of offenders in Hong Kong. Hopefully, this would be able to serve as an exploratory search into the psychological processes of offenders, and perhaps recidivism as well, and gain some insight into the explanation of criminal behaviour. It is proposed that a person may and will break the law when he or she cannot cope with life difficulties and eventually choose willfully or inadvertently to tackle with them by way of offending. The present study is an initial attempt to answer some of these questions.

METHOD

Those ex-offenders coming to four social therapy centres seeking community services were recruited into the sample. The survey was carried out in the form of a semi-structured interview, followed by the administration of a questionnaire.

Personal interviews of the ex-offenders attending the respective social therapy centres were conducted by their social workers. Much of their personal particulars were obtained either in person or from their files. They included such information as sex, age, education back ground, marital status, number of children, history of drug-taking and previous convictions.

A questionnaire was prepared with a view to gaining a more profound understanding of how ex-offenders coped with hardship of various sorts in life. The first part in the questionnaire listed out five common sources of hardship, the nature of which were respectively financial, inter personal, housing, occupational and acute-illness. The respondents were carefully instructed to rank in descend ing order from 1 to 5 the importance of hardship from the most to the least.

The second part of the questionnaire comprised 35 coping strategies. Respondents were required to indicate whether they would use each of these coping strategies in the presence of hardship by making a rating on a multi point evenly-spaced Likert's scale scoring from O to 10. A score of O implied that the coping strategy in question was never used and that of 10 was taken to mean that it was always used.

In order to ensure a high level of accuracy and efficiency, all data were manipulated and processed by computer. By tabulation, the frequency table displayed the response pattern to each item in the questionnaire for comparison and inference. In the analysis of the response pattern in respect of the coping strategies in case of hardship, inferences could only be made from how frequently each individual coping strategy was being chosen. In fact, embedded in the ways of coping there is a distinction between two general types of coping. The first, termed problem-focused coping, is aimed at problem solving or doing something to alter the source of the stress. The second, termed emotion-focused coping, is aimed at reducing or managing the emotional distress that is associated with (or cued by) the situation. So, each of the thirty-five coping strategies can be dichotomized into either problem-focused or emotion-focused coping strategy. In practice, coping strategies can also be classi fied by many other ways. One commonly used grouping is the further distinction between behavioural and cogni tive approach. Thus this would give rise to four catego ries, namely problem-behavioural (PB), problem-cognitive (PC), emotion-behavioural (EB) and emotion-cognitive (EC).

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient is a com monly used measure of correlation between two ordinal variables. In the procedure CROSSTABS, the summary statistic CORR is available to calculate the Spearman rank correlation coefficient for ordinal variables. Since PB, PC, EB and EC are all ordinal variables, their inter relationship can be explored using their mutual Spear man rank correlation coefficients.

RESULTS

(A) PERSONAL PARTICULARS

300 questionnaires were sent out to four social therapy centres in February 1995. A sample of 280 (93.33%) in size was obtained over the next four months. The response rate was regarded very high in view of the fact that firstly, our target group, in general, is reluctant to answer questions, particularly those referring to their attitudes or behaviour. So it is remarkable for them to answer more than 35 questions set in the questionnaire. Secondly, it was so time-consuming that it took each social worker about an hour to finish interviewing his or her client, and the latter would bear with the worker.

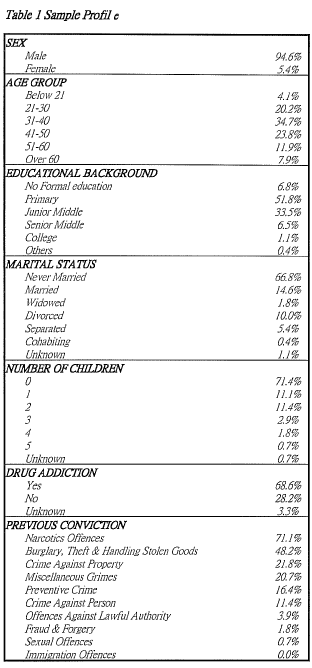

From the data, a profile of the respondents was produced in Table 1. Among the 280 respondents, an overwhelming majority were men (94.6 %). This was not a surprising finding, since the offending population in most other places has also a male predominance. Almost all of the respondents were adults aged 21 years or above and about one third of them (34. 7 %) were clustered in the 31-40 age-group. Concerning their education attainment, just over a half of the respondents (51.8 %) had finished Primary level and another one third (33.5 %) had received Junior Middle education. However, the remaining 6.8 % admitted that they had no formal schooling. As regards the marital status of the respondents, it was noteworthy that two third (66.8 %) of them had never got married. It also turned out that 71.4% of them did not have a child at all.

The bottom part in Table 1 listed ten categories of convictions using the classification system adopted by the Royal Hong Kong Police Force. The percentages of the respondents who had ever had these kinds of convictions were set down in descending order of frequencies. It was obvious that narcotic-related offenses were most com monly perpetrated by the respondents, being represented by 71.1 % of them. From the break-down of data, it is seen that these narcotic-related offenses committed were mainly concerned with possession of or trafficking in dangerous drugs and smoking opium. This finding of over-representation in this category of crime was at least in part explained by the fact that just over two third (68.6%) of the respondents admitted that they themselves had been for some time drug addicts. Moreover, almost a half of the respondents (48. 2 %) had committed common crimes such as burglary, theft and handling stolen goods, all in the nature of property off ending. Around 20 % (of them had committed also money-related crimes such as robbery and blackmail.

(B) SOURCES OF HARDSHIP

Five common sources of hardship, namely financial, interpersonal, housing, occupational and acute-illness in essence, were put slowly to the respondents to first delib erate for a while and then rank according to the degree of perceived impact to their daily living. It was noticed that financial problem assigned with a mean rank of 1.86 was considered by many more respondents to be the most important source of hardship. It was followed by housing (mean rank = 2.76), occupational (mean rank =2.91), interpersonal (mean rank = 3.67) problems and acute-illness (mean rank = 3.78).

Table 2 shows the cross-tabulation of "the most impor tant source of hardship" against "age-group". The calcu lated Pearson chi-square statistic was 31.16 with a p value of 0.05314 which was very close to 0.05. This would allow us to propose at about 5% significance level that selecting the most important source of hardship was correlated with age-groups. Based on the values of stand ardized chi-square residuals which are supposed to reflect the respective degree of dependency, we can further infer that :

(a) more respondents less than 21 years old viewed inter personal problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR=1.7);

(b) more respondents with their ages between 21 and 30 viewed interpersonal problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= 1.3); fewer respondents with their ages between 21 and 30 viewed acute-illness as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= -1.2);

(c) more respondents with their ages between 31 and 40 viewed financial problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR=1.4);

(d) fewer respondents with their ages between 51 and 60 viewed interpersonal problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= -1.3);

(e) more respondents more than 60 years old viewed acute-illness as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= 2.2); more respondents more than 60 years old viewed housing problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= 0); fewer respondents more than 60 years old viewed financial problem as the most important source of hardship than expected (SCSR= -2.3).

(C) COPING STRATEGIES

35 pre-selected coping strategies were included in the questionnaire. Each of them was rated one by one by the respondents according to the frequency of their choosing it as a coping tactic, on a 10-point scale.

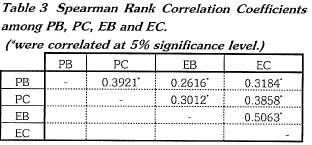

The ranks for the four categories of coping strategies PB, PC, EB and EC were calculated according to the adopted grouping. It was found out that all four of them had mean ranking between the values of 3 and 4, with Problem-Cognitive having the highest mean rank (3.97) followed by Emotion-Cognitive (3.87), Emotion-Behav ioural (3.34) and Problem-Behavioural (3.16).

In Table 3, the Spearman rank correlation coefficients between each of the any two ordinal variables PB, PC, EB and EC were all positively correlated at 5% signifi cance level with one another. This means that using one of the approaches does not necessarily imply giving-up of other means to the problem by another approach. It follows further that the respondents, like most Chinese people, tend to be eclectic in managing their problems.

In particular, the cross-tabulation of "selecting behav ioural approach to handle a problem" against "education background" gave rise to a significant finding. The Pear son chi-square statistic between these two variables was calculated to be 75.41 which could be converted to a p value (0.00301) that was considerably less than 0.05. So we can conclude at 5% critical level that selecting behav ioural approach to handle a problem was significantly correlated with education background.

Interpretation using the standardized chi-square resid uals suggests that (i) more respondents without formal education frequently (as illustrated by a rank value of 8) handled a problem using behavioural approach than expected (SCSR=4.0); (ii) more respondents with senior middle level occasionally (as suggested by a rank value of 5) handled a problem using behavioural approach than expected (SCSR =2. 90); more respondents with college or above level occasionally (at a rank value of 6) handled a problem using behavioural approach than expected (SCSR=4.0).

With the cross tabulation of "selecting behavioral approach to treat the emotion caused by a problem" against "age groups", the Pearson chi-square statistic was 50.14 with p-value (0.04676) which was smaller than 0.05. So we can conclude at 5% significance level that there was an age effect on relying on emotion-focused behavioral approach to handle a problem. Again, based on the standardized chi-square residuals we can see that (i) more respondents less than 21 years old occasionally (with rank 6) used the emotion-focused behavioral approach than expected (SCSR= 2.1); more respondents with ages between 31 and 40 occasionally (with rank 5) used the emotion-focused behavioral approach than expected (SCSR= 2.2); (ii) respondents with their ages above 60 tended not to use emotion-focused behavioral approach to handle a problem.

With the cross-tabulation of "selecting behavioural approach to handle a problem" against "the most impor tant source of hardship", the calculated Pearson chi square statistic was 50.07, corresponding to a p-value (0.05967) which was not too much away from the value of 0.05, the pre-set significance level for induction. Therefore, it is very likely that selecting behavioural approach to handle a problem was not unrelated to the most important source of hardship perceived. On this assumption, in terms of the standardized chi-square residuals, we notice that (i) those respondents who viewed acute-illness as the most important source of hardship tended to handle a problem more behaviourally; (ii) those respondents who viewed housing problem as the most important source of hardship tended to handle a problem more behaviourally; (iii) those respondents who viewed financial problem as the most important source of hardship tended not to handle a problem more behaviourally.

DISCUSSION

Overally speaking, financial hardship stood out as the most important source of hardship which they had to deal with, and vast majority of the respondents would rank it as the first or second in the rank order across all age-groups,. This is understandable in not only our sample under investigation, but also in any offending population, as convicted offenders are reported to come mostly from lower socio-economic classes and their crimes are often related to materialist or monetary gains, not infrequently aimed to solve financial difficulties. They are also likely to be unemployed intermittently. This is all confirmed in our study.

With respect of individual age-groups, it was found that there seemed to be a trend of salience of hardship of a different nature at different stages of life span. Interper sonal difficulties were more likely to be encountered by the youngest age group. Middle-age adults found financial situation most stressful to handle. In comparison, older adults saw the occurrence of acute illness as a harsh reality and practical needs of accommodation as a matter of necessity, yet often in practice beyond their means. They are usually less likely to see hardship as an oppor tunity for personal growth or an challenge. Conversely, it is conceivable once available that youngsters will not usually consider acute illness and housing as something that should captivate their immediate attention and urgent action.

The results of the present study indicated that in the face of hardship in life, most people smoked cigarettes, talked to a professional worker or others for information or to work out a plan or to get out from frustration. Apart from the first chosen strategy, the responses· to cope were rather acceptable, if not adaptive. Nevertheless, it is alarming to note that the respondents would consistently tend to smoke cigarettes whenever they met with usual life stresses. Where smoking is in reality a fairly common habit, this behaviour as the common reaction to stress, irrespective of the nature or source of stress and in almost all age-groups, should not be ignored, not just because smoking can and indeed do bring about harm to health of self and others, as propagandized by the government, but also smoking by and in itself is a relatively passive coping response. It may be argued that smoking may be serving a coping function. Environmental stress provokes negative mood states such as depression, anxiety, and anger in the person undergoing the stress, which in turn elicit coping responses, including maladaptive ones such as smoking. Some would say that smoking at leisure may facilitate mental relaxation and foster forward planning, yet coping by active problem-solving was not demonstrated among the most frequent strategies employed by the respondents.

It was further revealed that those under the age of 21 would resort to alcohol, drugs, and even foods. This course of action is taken as a passive or palliative coping coupled with a proclivity to withdraw from reality or merely distract one from the issue.

It is well recognized that substances such as tobacco and alcohol are used by some persons at some times to deal with the stress of modern society. These substances may be used as a coping mechanism for two independent reasons: They can reduce negative affect or can increase positive affect (Marlatt, 1979). Substance use as a coping strategy may reflect not only a belief that it would reduce negative affect to manageable proportions but also a belief that it can induce positive affect.

Although substance use does not alter circumstances, people believe that alcohol will ease negative affect associated with stressful events and stressful life conditions (Deardorff et al., 1975; Wilson & Abrams, 1977). People who believe this would be expected to be more likely to take the drug to help them cope with these maladies. Since resources such as personal control and alternative coping mechanisms are inversely related to drinking to cope in the face of stressful life conditions (Marlatt, 1979), people under stress or with fewer psychological resources show a greater overall tendency to use alcohol or drugs to help handle tension Enduring strains, because of their long-term nature, would be most likely to create risk for habitual substance abuse (Shiffman & Wills, 1985). However, it should be brought to public knowledge that drinking alcohol or taking drugs are not necessarily effective methods for coping with many lif e problems (Walters, 1994).

There is no doubt that coping serves important func tions in the service of human adaptation, and in the long term, adaptive functioning requires maintaining a delicate balance between both problem-focused and emotion focused coping activities. These basic coping strategies are not mutually exclusive. Most people react to stressful conditions with complex combinations of the major forms of coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980; Lazarus & Folk man, 1984).

Coping processes are influenced by available resources for coping, which include skills and abilities, social resources, physical resources, tangible resources, psycho logical resources, and institutional, cultural, and political resources (Eckenrode, 1991). Some resources affect the options for coping in a given situation. Money greatly increases the coping options in many stressful situations by providing more effective access to legal, medical, financial, and other professional assistance. Knowledge, such as of a bureaucratic process, can also increase options for coping. Other resources, such as energy and morale, primarily affect coping persistence. It is quite natural that people who have more personal and environmental resources seem to rely on active coping efforts and less on avoidance coping (Holahan & Moos, 1987). People who believe in their self-efficacy are more persistent in their coping efforts than are people who doubt their self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982).

While coping effectiveness is a function of both the stressful situation and the coping strategy employed (Ruble, Costanzo & Oliveri, 1992), coping is generally less effective among people exposed to a chronic diffi culty. Some situations are so intractable and so beyond the control of individuals who experience them, that en durance is more efficacious than action that would be useless, perhaps even harmful, if it sapped energy or in creased frustration (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978).

But people who cope with stress by minimizing or avoiding threatening events may find themselves coping effectively with short-term threats (Wong & Kaploupek, 1986; Kiyak, Vitaliano & Crinean, 1988). In fact there is some evidence that passive coping can be associated with good emotional adjustment (Eckenrode, 1991). However, if the threat is repeated or persists over time, a strategy of avoidance may not be so successful. The chronic use of avoidance as a coping style constitutes a psychological risk factor for adverse responses to stressful life circumstances (Quinn, Fontana & Reznikoff , 1987). This is what usually happens to sub-populations like off enders. In this context, it is reasonable to expect that the re spondents tended to respond to problems in the areas of acute illness and housing behaviourally, as measures to solve them dictate actions rather than mere thinking or planning. Cognitive approach is less appropriate in this respect. It might be less straightforward to explain the finding that it was less likely for the respondents to treat the financial problem in a behavioural manner. It is sur mised that the target group is normally in want of resour ces. They would have made every effort to augment their assets and enhance their financial abilities if and when ever feasible. In the end, financial hardship remained as the major, the last and the least easily manageable prob lem, since probably they had already tried out all means before they had assumed such an attitude. All they could do in the lurch was to sit back, or to ponder further on the ways and means, or to forget about it for a while. It seems that coping depends not only on the available coping strategies an individual uses but also on the prob lem or situation he or she confronts. Situational factors appear to be more influential than personality character istics in shaping the particulars of the coping process (Fleishman, 1984).

It also appears from the present study that there was a propensity for those who had received fewer years of formal education to endorse a behavioural approach of coping towards hardship, although the converse, that is, the more educated respondents would solve the problem by cognitive approach, was not borne out in the statistical analysis.

CONCLUSION

In order to survive and to adjust effectively in the community, ex-offenders require special skills and ade quate information. Skills may involve techniques for compensating for social and psychological inadequacies, pacing oneself , preparing for anticipated embarrassing situations, and the like. It is envisaged that through retraining ex-off enders will be able to meet the demands of the environment, cope successfully with life hardships, and adapt to their reality, without necessity to resort to illegal activities to satisfy their basic and other needs.

In the end, an effective coping training program would have the double aim of reducing distress by increasing the individual's effectiveness at coping with environmental stress, thereby reducing the need to turn to cigarettes for coping assistance, and increasing the repertoire of non harmful coping strategies to use on those occasions when distress remains high .. The program may also help peo ple who tend to respond to stressful situations with anger and hostility. Effective coping patterns can be substituted for maladaptive ones, thereby reducing the frequency and intensity of negative outcomes and hostile responses. Over and above the interpersonal value that is inherent in reducing hostile response, evidence that hostility is a pre dictor of further criminal activities.

It can never be over-emphasized that because of the diversity of people's needs, individualization of the reha bilitation plan is needed. These plans should be based on an assessment of client skills relative to a particular envir onment to ensure that the actual skills being taught to the specific client are the skills he or she will need in that environment. To the extent that necessary skills can be clearly conceptualized and broken down into specific components, they can be more readily and effectively taught.

Hence, in contrast to the concept of group work (Tow], 1995) which is pervasive in the prison setting, the idea of individualized program to enhance the coping capacity of ex-offenders should now be explored. After all, it is almost always the discharged offenders who are likely to re-offend and relapse into criminal career. The future direction of crime prevention should seriously take this into consideration.

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am.Psychol., 37: 122-147.

Berkowitz, L. (1970) The contagion of violence. In W.J. Arnold & M.M. Page (Eds.) Nebraska symposium on motivation. Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska Press.

Carver, C.S.C., Scheier, M.F. & Weintruab, J.K (1989) Assess ing coping strategies. J. Person. Soc. Psychol., 56(2): 267-83.

Deardorff, C.M., Melges, F.T., Hout, C.N. & Savage, D.J. (1975) Situations related to drinking alcohol. J.Stud.Alcohol, 36: 1184-95.

Eckenrode, J. (1991) The social context of coping. New York: Plenum.

Fleishman, J.A. (1984) Personality characteristics and coping patterns. J.Hlh.Soc.Behav., 25: 229-44.

Folkman, S. & Lazarus, R.S. (1980) An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Hlh.Soc.Behav., 21: 219-39.

Gibbons, D.C. (1977) Society, crime and criminal careers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Goldstein, M.J. (1975) A behavioral scientist looks at obscenity. In B.D. Sales (Ed.): The criminal justice system. New York: Plenum.

Holahan, C.J. & Moos, R.H. (1987) Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. J.Person.Soc.Psychol., 52: 946-55.

Kiyak, H.A., Vitaliano, D.P. & Crinean, J. (1988) Patients' expectations as predictors of orthognathic surgery outcomes. J. Hlh.Psychol., 7: 251-68.

Lazarus, R.S. & Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

Marlatt, G.A. (1979) Alcohol use and problem drinking. In P.C. Kendall & S.D. Hollon (Eds), Cognitive behavioral inter vention. New York: Academic.

Pearlin, LI. & Schooler, C. (1978) The structure of coping. J.Hlh.Soc.Behav., 19: 2-21.

Petersen, E. (1977) A reassessment of the concept of criminality. New York: Halstead.

Quinn, M.E., Fontana, A.F. & Reznikoff, M. (1987) Psychologi cal distress in reaction to lung cancer as a function of spousal support and coping strategy. J.Psychosoc.Onc., 4: 79-90.

Ruble, D.N., Costanzo, P.R. & Oliveri, M.E. (1992) The social psychology of mental health. New York : Guilford.

Shiffman, S. & Wills, T.S. (1985) Coping and substance use. New York: Academic.

Toch, H. (1977) Police, prisons, and the problems of violence. NIMH, Wash., DC: US Govert Printing Office.

Tow] G. (1995), Group Work in Prisons. DCLP occasional paper No. 23. BPS, Leicester.

Walters, G.D. (1994) Drugs and crime in lifestyle perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Wilson, G.T. & Abrams, D. (1977) Effects of alcohol on social anxiety and physiological arousal: Cognitive versus pharma cological processes. Cognitive Ther. Res. 1: 195-210.

Wong, M. & Kaloupek, D.G. (1986) Coping with dental treat ment: The potential impact of situational demands. J.Behav.Med., 9: 579-98.

Bernard W. Lau MB.BS; MRCPsych; DPM, Honorar y Consultant Psychiatrist, Ha uen of Hope Hospital; Baptist Hospital; St. Paul's Hospital

Bonnie Tin BSc, MPhil, Research & Development Of ficer, Society for Rehabilitation of Offenders, Hong Kong

Correspondence: Rm. 703, Capitol Centre, Jardine's Bazaar, Causeway