Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry (1996) 6 (1), 23-28

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Summary

Burden of care and its determinants were assessed in families of 90 patients, 30 each with a DSM III diagnosis of dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. Mean score on Family Burden Interview schedule of Pai and Kapur was 11.83 (S.D. = 5.90); 80% of the families reported moderate and 19% severe burden. Subjective burden was proportionately less, reflecting tolerance of relatives. Only two determinants, longer duration of illness and higher levels of patient dysfunctions, correlated significantly and consistently with the extent of burden. The study shows that burden among families of neurotic patients is considerable. The need for routine evaluation of burden of care is stressed with a view to render practical help to the families of the patients.

Keywords: burden of care, generalized anxiety disorder, dysthymia, obsessive compulsive disorder

INTRODUCTION

With the rise of community psychiatry, one social parameter which has received some attention is the burden of care of psychiatric patients on their caregivers. Family burden was used as one of the measures of success of community oriented programmes.

According to Platt (1985), burden of care refers to the presence of problems, difficulties or adverse events which affect the lives of significant others of patients with psychiatric illness. The first study of burden was conducted in 1955 by two sociologists Clausen and Yarrow in USA. Since then other studies have explored family burden in groups of unselected psychiatric patients as well as selected patient groups such as schizophrenics. Most of these studies have found a high prevalence of burden among families of mentally ill patients. Research attention has been focused mostly on patients with psychosis especially schizophrenia. There are a few recent studies dealing with affective disorders and almost none with neurotic illness except when such patients have been included in a group of unselected psychiatric patients (Fadden et al., 1987). The fact that patients with psychosis generate more burden is probably undisputed. However, research also shows that any mental illness of some duration and persistence is bound to result in burden, the extent being determined by a number of factors. Further, several studies have documented impaired functioning, marital disharmony and marital conflict among couples with a member suffering from neurosis (Nelson et al.,1970; Collins et al.,1971; Hinchcliff et al.,1971). Certain Indian studies have also found significantly disturbed marital relationship and disturbed communication patterns in patients with neurosis and their spouses (Mayamma & Satyavathi, 1985). These trends suggest that families of patients with neuroses are also likely to experience considerable burden.

Thus, the aims of the present study were as following:

- To estimate the extent of burden in families having a member withneurosis.

- To study the effects of sociodemographic variables, illness variables and amount of dysfunction of the patient on the extent of

METHOD

The sample consisted of 90 consecutive cases (30 each of dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder as per DSM-III of American Psychiat1ic Association, 1980) were selected from the patient population attending the psychiatric services of the Institute.

INCLUSION CRITERIA

The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows:

(i) of either sex in the age range of 15 - 45 years

(ii) diagnosis of either dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder or obsessive compulsive disorder as per DSM-III criteria.

(iii) illness duration of 2 years or more.

(iV) Staying with a relative currently and at least for 3 previous years.

The inclusion criteria for relatives were:

(i) healthy adult aged 18 years or more

(ii) staying with the patient currently and at least for 3 previous years.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

The followings were excluded from the study:

(i) Patients with any axis II diagnosis, chronic physical illness, organic brain disease or substance abuse.

(ii) Families with any other member with a psychiatric or chronic physical illness.

STUDY GROUPS

The sample was divided into 3 groups of 30 patients; these were the dysthymic disorder group (DD), generalized anxiety disorder group (GAD) and the obsessive compulsive disorder group (OCD).

INSTRUMENTS

Family Burden Interview Schedule

This semi-structured interview schedule was the principal instrument of this study. It has been devised keeping Indian conditions in mind and has been used in numerous studies with various categories of psychiatric patients (Pai & Kapur, 1981). It has 24 items grouped under 6 areas of burden, namely i) financial burden, ii) disruption of routine family activities, iii) disruption of family leisure, iv) disruption of family interactions, v) effect on physical health of others and, vi) effect on mental health of other. Each item is rated on a 3 point scale- zero indicating no burden, one indicating moderate and two indicating severe burden. It has a standard question (How much would you say you have suffered owing to the patient's illness - severely, a little or not at all ?) to assess subjective burden which is also on a 3 point scale. Objective burden is the total score. Global burden is according to the severity of burden experienced and is rated as no burden, moderate burden and severe burden. This schedule has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of burden despite certain limitations.

Dysfunction Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ)

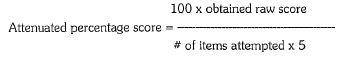

The DAQ (Pershad et.al., 1985) which has been developed in this Department, has 50 items grouped under 5 areas viz. social, vocational, personal, family and cognitive. This scale was devised to measure functioning of the patient subsequent to his/her becoming ill. Each area which the scale assesses has 10 items and each item has 5 alternative answers indicating the same, better or worse level of functioning compared with the premorbid level of functioning. Rating of 1 indicates better than premorbid level of functioning and rating of 4 indicates rapid deterioration of functioning. Some items may not be applicable to a particular patient. An attenuated percentage score is calculated by the following formula:

An attenuated percentage score of 40 in each scale would mean no dysfunction compared with a reference point of premorbid level. A score less than 40% would mean better level of functioning than the premorbid level and a score more than 40% means dysfunction.

PROCEDURE

The patients were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Relatives accompanying the patient were interviewed to determine the person experiencing maxi-mum burden. In our country, patients are usually accompanied by spouse or parents. In some instances, sibs or children of the patients attend the clinic with their sick relatives. If such a person was not available the next most suitable relative was designated as the informant depending upon whether or not the patient lived with this relative as mentioned in the inclusion criteria. Informed consent was taken and sociodemographic and clinical details were recorded. Then a semi-structured interview was undertaken with the relative to assess family burden. Following this the DAQ, was administered to the relative to determine the patient's level of dysfunction. All assessments were done only once and by one investigator (SC) only. It should also be noted that the assessment of burden and dysfunction were not done on a "blind" basis and as such inadvertently a certain degree of "bias" might have resulted.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic parameters of patients

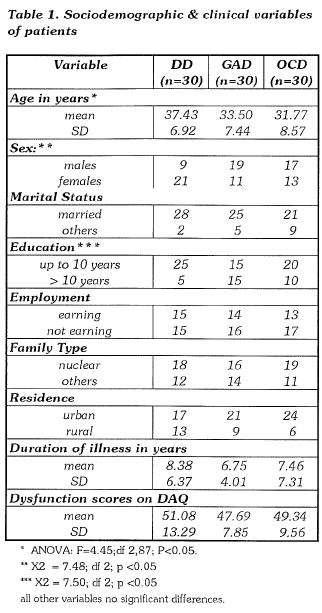

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic parameters of the patients. Though no attempt was made to match the groups, the sociodemographic factors are more or less similar. The dysthymic group had a higher mean age, more number of females, and more patients with less than 10 years of education. However, as shown later these sociodemographic factors did not have significant influence on burden; therefore for all purposes the groups were considered to be homogeneous.

Sociodemographic parameters of relatives

Of the 90 relatives accompanying the patients 59 (66%) were spouses, 13 (14%) were parents, 15 ( nearly 16%) were sibs or children. Only 3 patients were accompanied by other relatives. Mean age of the relatives was 37.33 (SD 11.27)years; the majority were males (68%), married (90%), with less than 10 years of formal education. There were no statistically significant differences with regard to any of the sociodemographic variables among relatives in the 3 study groups.

Duration of illness and dysfunction

The mean duration of illness was 8.38 (SD 6.37) years in the dysthymic group, 6.75 (SD 4.0l)years in the generalized anxiety and 7 .46 (SD 7.31) years in the obsessive compulsive group. Mean scores of dysfunction in the DD group was 51.08 (SD 13.29), 47.69 (SD 7.85) in the GAD group and 49.34 (SD 9.56) in the OCD group. Comparison of mean duration of illness and mean scores of dysfunction among the 3 groups did not reveal statistically significant differences (Student's t test).

Extent of family burden

Table 2 shows the extent of subjective and objective family burden. The ratings of objective burden are shown in 2 ways:- i) mean scores of burden which is the mean of ratings on all items of the scale and ii) a global rating of burden which divides the families in those with no burden, moderate burden or severe burden. The mean score for total sample was 11.83 (SD=5.90) and there were no statistically significant differences among the 3 study groups with regard to mean scores of burden. For comparison of means in objective burden Student's t test was performed.

When global objective burden is considered, 80% of the entire sample of families reported expe1iencing moderate burden. About one fifth (19%) were rated to have severe burden whereas only one family considered it-self to have no burden. Subjective burden or burden carried in a subjective sense by the relatives is also shown in Table 2. If the proportion of families reporting subjective burden is compared with the global objective burden ratings it can be seen that about a quarter of the families (26%) experiencing moderate or severe burden did not perceive any subjective burden. For Global Objective Burden (excluding 1 subject in "no burden" : X2 = 3.96: df 2; p > 0.05 and for Subjective Burden : X2 = 2.60; df 4; p > 0.05.

DETERMINANTS OF BURDEN

The influence of va1ious sociodemographic factors, duration of illness and the amount of dysfunction on burden was investigated in the 3 study group. Only two factors - duration of illness and amount of dysfunction - showed a consistent and statistically significant relationship with burden. Thus, longer duration of illness and higher levels of dysfunction of the patient both correlated with higher extent of burden across all of the study groups. Other va1iables viz. - age, sex, marital status and education of either the patient or relative, employment status of the patient, family type and residence did not show a consistent correlation with extent of burden. These results are depicted in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here pertain to only one aspect of burden i.e. the extent of burden in families of patients with neuroses. Our results show prevalence of considerable family burden among patients with neuroses. Most studies dealing with patients of psychoses have shown that 90% or more of the families report some amount of burden. In this study 99% of the families rep01ted some amount of burden; of them 80% had moderate burden and 19% felt severe burden. A study from our country by Gupta et al.(1991) assessed family burden in patients with anxiety neurosis and neurotic depression using the same scale as that of the present study and reported that 95% of the families had moderate burden while only 5% had severe burden. The propo1iion of families with severe burden in the present study is higher, probably because of the longer duration of illness of the patient sample. Studies by Gautam & Nijhawan (1984) and Raj et al. (1991) using the interview schedule of Pai and Kapur ( 1981) have found mean scores of family burden in schizophrenia to vary from 18 to 20, whereas the mean score of 15 was obtained in a sample of patients with affective disorders in one study by Chakraba1ii et al.(1992). Thus, the amount of burden in the present sample of patients with neuroses was less than that found among patients with schizophrenia or affective disorders.

Subjective burden, a concept initially proposed by Hoenig and Hamilton (1966) refers to subjective distress or burden carlied in a "subjective" sense by the relatives. A number of studies since then have shown a great deal of discrepancy between subjective and objective burden with relatives inva1iably failing to acknowledge subjective burden and tolerating a number of problems encountered in ca1ing for the patient. This study showed that about a quarter of the families rated as expe1iencing moderate or severe burden perceived no subjective burden. This figure is comparable to Hoenig and Hamiltons (1966) study which demonstra-ted that 25% of the families carrying a good deal of objective burden reported no subjective burden. Part of the reason for this could be the nature of the screening question for rating subjective burden. The instrument of Pai and Kapur has only 1 question which assesses subjective burden and that too in a general way. This may be inadequate to elicit subjective burden and perhaps warrants more in-depth interviewing or evaluation of the relative to provide an accurate estimate of subjective burden.

What are the factors which determine the extent of burden? There is very little consensus in the literature regarding the effect of different factors. In the present study only 2 factors - a longer duration of illness and higher levels of dysfunction in the patients - correlated significantly and consistently with the extent of burden. Other studies by Brown et al. (1966) and Pai & Kapur (1982) have also shown that prolonged illnesses and high levels of dysfunction result in a greater amount of burden. In addition among affective disorders, Chakraba1ii et al. (1992) have shown that the two most important predictors of burden were the amount of dysfunction and duration of illness. However, this does not mean that other sociodemographic factors and clinical va1iables have no role in determining burden. It is possible that these parameters are more important in shaping the pattern or typology of burden. This complex relationship between burden and its determinants needs further careful study before a firm idea emerges.

Finally, despite the preliminary nature of this investigation certain conclusions can be drawn the primary one being that there is a considerable prevalence of burden among families of patients with prolonged neuroses, a prevalence similar to that found among patients of psychoses. With reference to the rating of total global burden in the present work, reporting of subjective burden is prop01iionately less, suggesting that relatives are prepared to tolerate a great deal of burden before they complain. Fu1ther studies are needed to explore the pattern of this burden and the influence of va1ious factors on it. Evaluation of burden should in fact form a pa1t of the routine assessment of patients with psychiatric disorders including neurosis. The next logical step would be to devise strategies to alleviate burden. Again, these observations have been made by vi1tually every investigator in this field but the translation of these simple p1inciples into clinical practice has been somewhat lagging; hence the re-emphasis despite the risk of being repetitive.

REFERENCES

Ame1ican Psychiatric Association. (1980) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition). Washington DC:APA.

Brown, G.W., Bone, M., Dalison, B. & Wing, J.K (1966) Schizophrenia and Social Care. London: Oxford University Press.

Chakrabarti, S. Kulhara, P. & Verma, S.K (1992) Extent and determinants of burden among families of patients with affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 86,247-252.

Clausen,J.A. & Yarrow,M.R. (1955) The impact of mental illness on the family. Journal of Social Issues, 11,6-11.

Collins,J., Kreitman, N., Nelson, B. & Troop,J. (1971) Neurosis and marital interactions: III. Family roles and functions. British Journal of Psychiatry, 119, 233 -242.

Fadden,G., Bebbington,P. & E:upiers,L. (1987) The burden of care: The impact of functional psychiatric illness on the patient's family. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150,285-292.

Gupta,M., Giridhar, C. & Kulhara, P. (1991) Burden of care of neurotic patients: correlates and coping strategies in relatives. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 7,8-21.

Gautam,S, & Nijhawan,M. (1984) Burden on families of schizophrenia and chronic lung disease patients. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 26,156-159.

Hinchcliff ,M.K , Hooper, D. & Roberts, F.J. (1978) The Melancholy Marriage. Chichester: Wiley.

Hoenig,J. & Hamilton, M.W. (1966) The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 12,165-176.

Mayamma, M.C. & Satyavathi,K (1985) Disturbances in communication and marital disharmony in neurotics. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 27,315-319.

Nelson,B., Collins,J., Kreitman,N. & Troop,J. (1970) Neurosis and marital interaction: II. Time Sharing and social activity. British Journal of Psychiatry, 117, 47 -58.

Pai,S. & Kapur,R.L. (1981) The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an assessment scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 138,332-335.

Pai,S. & Kapur,R.L. (1982) Impact of treatment intervention on the relationship between dimensions of clinical psychopathology, social dysfunction and burden on the family. Psychological Medicine, 12,651-658.

Pershad,D., Verma,S.K & Malhotra, AK (1985) Measurement of Dysfunction and Dysfunction Analysis Questionnaire (DAQ). Agra: National Psychological Corporation.

Platt,S. (1985) Measuring burden of psychiatric illness on the family: an evaluation of some rating scales. Psychological Medicine, 15,383-394.

Raj, L., Kulhara, P. & Avasthi,A. (1991) Social burden of positive and negative schizophrenia. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 37,242-250.

S. Chakrabarti MD Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research

Kulhara MD,FRCPsych, MAMS Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research

S.K. Verma PhD,DM & SP Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research

correspondence: Dr.P.Kulhara, Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER, Chandigarh - 160 012,