Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2004;14(4):2-8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

KK Wu, SK Chan

Dr Kitty K Wu, PhD, Department of Clinical Psychology, Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Sumee K Chan, MSocSc, Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Kitty Wu, Department of Clinical Psychology, Caritas Medical Centre, 111 Wing Hong Street, Shamshuipo, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China.

E-mail: wukyk@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 31 December 2004; Accepted: 15 April 2005

Abstract

Objective: This study examined the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised.

Patients and Methods: The first phase of the study included 575 patients who had undergone a motor vehicle accident. The Chinese Impact of Event Scale-Revised, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, and General Health Questionnaire-20 completed by the patients 1 week after the accident were evaluated. In the second phase of the study, 46 patients were interviewed 1 month after the accident for administration of the Chinese Impact of Event Scale-Revised and the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale.

Results: A 2-factor structure accounting for 58% of the variance was identified. The validity of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised as a measure of psychological distress after a traumatic event was supported by the moderate correlations between various Impact of Event Scale-Revised subscale scores and the General Health Questionnaire-20 and the strong correlations between scores in the Impact of Event Scale-Revised and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist. The Chinese Impact of Event Scale-Revised had good sensitivity and specificity for the screen- ing of post-traumatic stress disorder based on the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale.

Conclusion: The Chinese version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised was found to have satisfactory psychometric properties.

Key words: Accidents, traffic, Stress disorders, post-traumatic, Wounds and injuries

Introduction

The Impact of Event Scale (IES) was widely used for ex- ploring the psychological impact of a variety of traumas.1 The theoretical formulation of the IES is based on clinical studies of psychological response to stressful events and on the theory of the stress response syndrome.2 According to the stress response theory, the 2 common responses to stress involve intrusion and avoidance. These 2 responses tend to oscillate during the same time period. Avoidant behaviour serves to restore emotional equilibrium, prevent emotional flooding, and reduce conceptual disorganisation. However, these defensive efforts are disrupted by intrusive experiences leading to a dread state. To restore stability, people react with heightened defensive control. Although avoidance of painful thoughts may reduce the state of dread, such avoidance may also prevent adaptation to the traumatic experience and lead to persistent post-traumatic stress. On the basis of this assumption, the IES was developed to study the intrusive experience and avoidant behaviour in reaction to traumatic events. As noted by Weiss and Marmar,3 research using the IES has helped to provide evidence that contrib- utes to the adoption of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the nomenclature; PTSD was first recognised as a diagnostic entity in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-III (DSM-III).4 According to a recent review, the psychometric properties of the IES have been demonstrated in many studies and used to research the psy- chological impact of various traumatic life events. Results have indicated that the IES's 2-factor structure is stable for different types of events, and that the scale has convergent validity with diagnosed PTSD.5

Weiss and Marmar revised the IES by including items to track responses in the domain of hyperarousal symptoms.3 This revision was consistent with the inclusion of hyper-arousal symptoms in the diagnostic criteria of PTSD in DSM-IV.6 Together with the 15 items in the original IES, the IES-R comprises 22 items. The sound psychometric properties of the IES-R in English and Chinese have been demonstrated in previous studies.3,7

Compared with other self-report measures that are spe- cifically associated with the PTSD such as the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist,8 the strength of the IES-R lies in the vast amount of literature based on the use of the original IES. The use of the IES-R allows for replication of previous studies and comparisons of findings between previous and new research areas. Since the IES-R focuses on the impact of an event and is relatively independent from any specific disorder, the IES-R can serve as an instrument to examine the associated features of various psychological syndromes. The IES-R is also useful for treatment studies.9,10 Since the IES-R is one of the few PTSD-related self-report measures that has been translated into different Asian languages and validated in different studies, the use of the IES-R allows comparison of results between studies of different traumatic events for Asian populations.7,10-12 The IES-R has also been used in research investigating psychological factors associ- ated with the development of PTSD such as coping strategy and perceived threat.13 Compared with a structured inter- view for assessing PTSD features, the IES-R is brief and easy to administer.

However, the IES-R has not been used in research as frequently as the original IES. The slow transition from the IES to the IES-R for trauma is probably related to the availability of other self-report measures for PTSD, the lack of studies examining the psychometric properties of the IES-R, and its relationship with other measures of posttraumatic stress. The validity of the IES-R as a screen- ing tool for PTSD also requires examination by studying its relationship with the results of diagnostic interviews, and by using a clinical population with PTSD.

Studies of the IES-R and the Chinese IES-R have so far found an underlying structure with 1 factor.3,7 This result is inconsistent with Horowitz's stress response theory1 and the factor structure of the original IES. The 1-factor model identified for the IES-R is also not consistent with the dimensionality of PTSD found in recent studies, which suggests that although the 3-symptom clusters of PTSD according to the DSM-IV might not provide the best conceptualisation of symptom dimensionality, a 4-factor model provides the best fit to the data.14,15

The reason for the failure to identify at least the original 2 factors (intrusion and avoidance) in IES-R studies is prob- ably related to the level of impact of the focused event for respondents when they filled in the IES-R. In the study by Weiss and Marmar, the data were collected approximately 6 weeks after an earthquake.3 Whether the earthquake had a personal impact (e.g., physical injury) on the respondents was not documented. In the study by Wu and Chan, a group of non-traumatised patients was studied.7 Respondents in these studies rated themselves as not affected or only a little affected by the PTSD features captured by the IES-R. On the other hand, in a group of 658 survivors of the sarin attack in the Tokyo metro system in 1995, a 2-factor model consistent with the stress response theory was identified for the Japanese version of the IES-R.12

As Hendrix et al suggested, the distinction between the 2-factor structure underlying the IES could be blurred over time, as the 2 factors may merge into 1 overall pattern of stress reaction or general level of distress.16 Zilberg et al also argued that an independent factor structure could be demonstrated only by patients with PTSD at the pre- therapy evaluation point.17 If these interpretations are valid, respondents who experience a certain level of distress following a traumatic event are suitable for research that examines the presence of independent factors underlying the IES-R.

This study examined the psychometric properties, inclu- ding reliability and factor structure, of the Chinese version of the IES-R among patients who attended the Accident and Emergency Department of the Caritas Medical Centre for treatment after a motor vehicle accident (MVA). In the first phase of the study, data were collected 1 week after the MVA. Given the personal impact and nature of the event, and how recently it occurred, data from these patients would be able to contribute to the understanding of the psy- chometric properties of the Chinese IES-R. The concurrent validity of the IES-R was examined by studying its rela- tionship with self-report measures of general psychological distress and post-traumatic stress. In the second phase of the study, the Chinese versions of the IES-R and Clinician- Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS-DX),18 which is a clinician-administered structured interview for the dia- gnosis of PTSD, were conducted for another independent group of MVA patients 1 month after the MVA to assess the Chinese IES-R as a screening measure for PTSD.

Patients and Methods

Patients

In the first phase of the study, MVA patients who consented to participate in the study were recruited from the Accident and Emergency Department from December 2001 to October 2003. The inclusion criteria included the following:

- required medical attention in the Accident and Emergency Department for an injury sustained in an MVA

- age 18 years or older

- able to read and write Chinese.

All respondents were required to complete the Chinese versions of the IES-R and General Health Questionnaire- 20 (GHQ-20)19,20 1 week after the MVA. Of the 1556 MVA patients who attended the Accident and Emergency Department during this period, 575 patients (37%) satisfied the inclusion criteria and gave written consent to partici- pate in the study.

379 men and 196 women, aged 18 to 89 years (mean, 39 years; standard deviation [SD], 14 years) participated in the study. The severity of physical symptoms for all respon- dents was rated by the physicians in the Accident and Emergency Department. 383 patients (67.0%) were rated as "mild: operation or plaster of Paris (POP) not required, Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) equal to 15"; 13 (2.0%) were rated as "moderate: operation or POP required, GCS equal to 15"; 177 (31.0%) were rated as "severe: requires hospital admission, GCS equal to 14 or 15"; and 2 (0.3%) were rated as "life-threatening: requires hospital admission, GCS of £13". 501 patients (87%) had been discharged from hospi- tal and 74 (13%) remained in hospital when they filled in the questionnaires.

To examine the validity of the Chinese IES-R, 127 patients were randomly selected to complete the Chinese version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL).8 There were 68 men and 59 women, who were aged from 18 to 87 years (mean, 39 years; SD, 15 years). The PCL was posted to the patients together with the IES-R and GHQ-20 one week after the MVA. The proportion of women for the subgroup of patients who filled in both the IES-R and the PCL was higher than for the group who were not required to complete the PCL, (c2 = 11.10; p < 0.001). The avoidance subscale score for the group completing both questionnaires (mean, 0.68; SD, 0.62) was lower than that for the group who did not complete the PCL (mean, 0.82; SD, 0.73) [F(1, 573) = 4.19; p < 0.05]. No significant dif- ference was found between this subgroup of respondents and those who were not required to complete the PCL in terms of age, severity of physical injury, and IES-R intru- sion and hyperarousal subscale scores.

To test the sensitivity and specificity of the Chinese IES-R for detecting PTSD as a clinical diagnosis, an inde- pendent group of 46 MVA patients admitted to the same Accident and Emergency Department from November 2003 to March 2004 who gave written consent to participate in the study were recruited for the second phase. As duration of distress for more than 1 month is required for the diagno- sis of PTSD, these patients were required to attend an inter- view 1 month after the MVA. The patients had to complete the IES-R before the CAPS-DX was conducted. The average time lapse between the MVA and the interview was 57.07 days (SD, 19.26 days). There were 32 men (70%) and 14 women (30%), aged from 18 to 78 years (mean, 38.67 years; SD, 13.51 years). The severity of physical injury for these participants was also rated. Among them, 35 (76%) were rated as "mild: operation or plaster of Paris (POP) not required, GCS equal to 15"; 1 (2%) was rated as "moderate: operation or POP required, GCS equal to 15"; and 10 (22%) were rated as "severe: requires hospital admission, GCS equal to 14 or 15". All of these patients had been discharged from hospital before they were interviewed. No significant difference was found between this group of patients and those who participated in the first phase of the study in terms of age, sex, and severity of physical injury.

Impact of Event Scale-Revised

The IES-R is a self-reported measure for capturing the level of symptomatic responses to a specific traumatic stressor occurring in the previous week.3 The degree of distress for each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from the absence of a symptom (0) to maximum symptomatology (4). There are 3 subscales of intrusion, avoidance, and hyper-arousal. Subscale scores are equal to the mean score of the non-missing items for the specific subscale.

The IES-R subscales have demonstrated high internal consistency with Cronbach's a ranging from 0.79 to 0.91, and test-retest reliability a ranging from 0.51 to 0.94.3 The Chinese version of the IES-R7 was found to have good internal consistency and favourable scale equivalence com- pared with the original English version. A mean score of 2.0 on a specific subscale was the appropriate cut-off point.

General Health Questionnaire-20

The GHQ-2019,20 is a widely used instrument spanning a range of items indicative of psychological distress. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the GHQ- 20 have been verified in local studies.21,22 For the present study, the simple Likert method (0 to 3) for scoring was adopted. The Chinese version of GHQ-20 was used in this study to examine the concurrent validity of the IES-R with another measure of general psychological distress.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

The PCL is a brief self-report inventory that can be used to assess 17 symptoms of PTSD.8 The non-military version that can be referenced to a specific traumatic event such as MVA was used in the study. The degree of distress for each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 to 5), ranging from the absence of a symptom to maximum symptomatology. Weathers et al found PCL to have high test-retest reliability (r = 0.9) and validity, as indicated by a k of 0.6 for diagno- sis of PTSD from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.23 PCL has been examined in cross-validation studies of populations who had been involved in different types of trauma such as MVA and sexual assault using diagnoses and scores from the CAPS.24 The Chinese version of the PCL has been verified in local investigations (unpublished data, 2005) and has been used to examine the concurrent validity of the IES-R with another measure of post-traumatic stress.

Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV

CAPS is a widely used structured interview for assessing

PTSD.25,26 According to a review of 10 years of research, CAPS has excellent reliability, yielding consistent scores across items, raters, and testing occasions. It has good con- vergent and discriminant validity, and sensitivity to clinical change. In the present study, CAPS-DX, which is a revised version of CAPS following the publication of the DSM-IV in 1994, was used. In previous studies of MVA patients, test-retest reliabilities were reported to be 0.90 to 0.98, and the internal consistency a was 0.94.27

The CAPS-DX includes a life event checklist for exam-ining criterion A of PTSD. For each of the 17 symptoms of PTSD in criteria B, C, and D, CAPS-DX assesses both the frequency of occurrence and the severity of symptoms at their worst during the previous month on a 5-point scale. For frequency of occurrence, each item is rated from never (0) to daily or almost every day (4). For symptom severity, each item is rated from none (0) to extreme (4). Thus, each item can have a score of 0 to 8. Specific scores for criteria B, C, and D can be found by adding the item scores belonging to the specific criteria together.

In the present study, an empirically derived rule for making a diagnosis of PTSD was adopted.28 According to this method, PTSD symptoms were considered present if the frequency of the corresponding CAPS-DX item was rated as 1 or higher and the intensity was rated as 2 or higher. The severity score of an item is equal to the sum of the frequency and intensity scores. To ensure both a significant overall level of PTSD symptom severity and a distribution of symp- toms corresponding to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, a total severity score of 65 or higher was required for making the diagnosis of PTSD.

The CAPS-DX was translated into Chinese and back- translated for the present study. The interviews were performed by a trainee who was studying for a Master's degree in clinical psychology. She was trained to conduct the CAPS-DX by one of the authors and by an audiovisual courseware for the CAPS-DX that was developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs Employee Education System of the USA. The interviews were tape-recorded for supervision by the same author. For examination of inter- rater reliability, 5 of the tape-recorded CAPS-DX interviews were randomly chosen and rated by a second assessor who was also a trainee studying for a Master's degree in clinical psychology. The second assessor was blinded to the rating of the chief interviewer. Between these 2 assessors, the inter-rater reliability for the judgement of individual crite- ria was 93% and for making the diagnosis of PTSD was 100%. These CAPS assessors were blinded to the result of the IES-R when they conducted and rated the CAPS.

Results

Psychometric Properties and Reliability of the Chinese Version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised

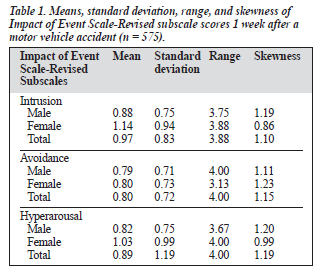

The means and standard deviations of the IES-R subscale scores for the study group were examined. As presented in Table 1, women had significantly higher IES-R intru- sion [F(1, 573) = 12.83; p < 0.01] and hyperarousal scores than men [F(1, 573) = 7.98; p < 0.01]. The rating for the severity of physical trauma was also significantly correlated with the IES-R intrusion (r = 0.22), hyperarousal (r = 0.18), and avoidance scores (r = 0.22; p < 0.001). The correlation coefficients between age and various IES-R subscale scores were not significant. The internal consis- tency of the IES-R was estimated using coefficient a for the intrusion, avoidance and hyperarousal subscales. The results of these analyses produced the following coefficients: intrusion (Cronbach's a = 0.92), avoidance (Cronbach's a = 0.86), and hyperarousal (Cronbach's a = 0.87).

The analyses on the split-half reliability of the IES-R yielded the following split-half correlation coefficients: intrusion (r = 0.90), avoidance (r = 0.87), and hyperarousal (r = 0.89). The corrected item-total correlations for the 3 subscales produced the following ranges of coefficients: intrusion (r = 0.61 to 0.83), avoidance (r = 0.42 to 0.73), and hyperarousal (r = 0.47 to 0.76). These data suggested that the internal consistency of the 3 subscales was high and that each of the individual items was consistent with the remaining items.

Factor Structure and Subscale Independence of the Chinese Version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised

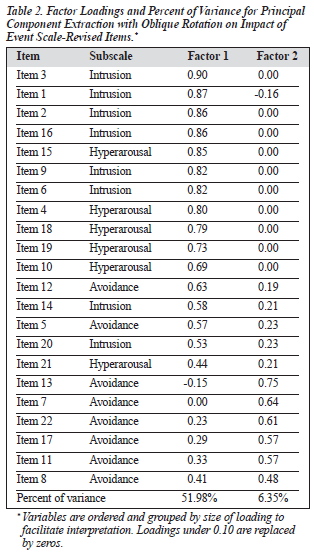

The factor structure underlying the Chinese IES-R was examined by principal component analyses. As shown in previous studies,3,7 the factors underlying the IES-R for mea- suring the psychological impact of a traumatic event were expected to be intercorrelated; thus, oblique rotation was used. Two different factor analyses were conducted. To explore the underlying factor structure, the number of factors was not specified in the first analysis. Because there were 3 symptom clusters for PTSD, 3 factors were specified in the second factor analysis. Barlett's test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001) indicating significant correlations between the variables. In the factor analysis without speci- fying the number of factors, 2 factors were extracted and shown to explain 58% of the variance. With the 2-factor solution, 34% to 75% of the original variance was explained for all variables. Loadings of variables on factors and percentages of variance are shown in Table 2.

The 2 factors had moderate to strong loadings on the items. One variable belonging to the avoidance subscale (item 8) was complex, which did not differentiate well be- tween factors; all other variables had moderate to strong loadings with only 1 factor. All except 2 items (items 5 and 12) loaded with the first factor belonged to the intrusion or hyperarousal subscales. All items loaded with the second factor belonged to the avoidance subscale. The correlation between the 2 factors was moderate (r = 0.54), which was consistent with the mean correlation (r = 0.63) between the intrusion and avoidance subscales of the original IES found in previous studies.5 The moderate correlation suggests that the 2 factors are relatively independent of each other, each of them representing a different type of reaction after a trau- matic event.

The interdependence of the intrusive and hyperarousal subscales in the IES-R was also demonstrated when the relationship between the 3 subscales was examined by Pearson's correlation analysis. The correlation between in- trusion and hyperarousal (r = 0.87) was stronger than those between intrusion and avoidance (r = 0.76) and between avoidance and hyperarousal (r = 0.76) [p < 0.001].

As in previous studies,3,7 the present results of the factor analysis and subscale correlation were consistent, suggest- ing that the items and subscales of the IES-R were related. However, the present study identified 2 relatively indepen- dent factors underlying the IES-R items. The first factor had moderate to strong loadings on items for intrusion and hyperarousal; the second factor had moderate to strong loadings on items for avoidance.

The factor loadings in the factor analysis with 3 factors specified were also similar to the previous factor analysis. The same items loaded more strongly with the first factor. Six items for avoidance loaded with the second factor in the previous analysis were divided when 3 factors were specified, with 2 items (items 7 and 13) loaded more strongly with the second factor, and the other 4 items loaded with the third factor. Thus, the factor loadings were not consis- tent with the 3 symptom clusters for PTSD, even when 3 factors were specified. The 2-factor structure with similar item-factor loadings was also identified in factor analyses adopting varimax rotation or principal factor analysis.

Relations between the Chinese Versions of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised, General Health Questionnaire-20, and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

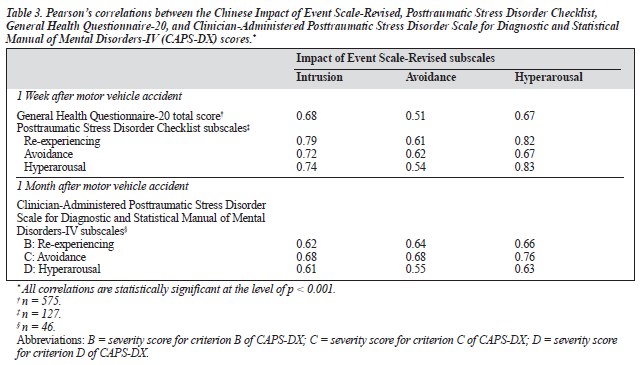

To examine the concurrent validity of the IES-R as a mea- sure of psychological distress, Pearson's correlations between the total score of the GHQ-20 and the 3 IES-R subscale scores were studied. As presented in Table 3, the correla- tion coefficients indicated that the relations were moderate, showing that the IES-R subscales contributed information that was not captured by the GHQ-20.

To examine the IES-R as a specific measure for post- traumatic stress, the relations between the IES-R and PCL scores were studied. Pearson's correlations between the subscales of PCL and IES-R were examined. As shown in Table 3, the correlation coefficients for the corresponding IES-R and PCL subscales indicated a moderate to strong relationship between the 2 measures.

Relations between the Chinese Versions of Impact of Event Scale-Revised and the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale

To examine the IES-R as a screening measure for PTSD, the relations between the IES-R and CAPS-DX conducted 1 month after the MVA were studied. Pearson's correlations between the IES-R subscale and CAPS-DX criterion scores were examined and presented in Table 3. The results indi- cated a significant relationship between the 2 measures.

As PTSD is characterised by the presence of all 3 domains of distressful features, the percentage of partici- pants passing the cut-off point for all 3 IES-R subscales was compared with the diagnostic result of the CAPS-DX. Among the 46 patients, 2 (4.3%) were found to have PTSD according to the CAPS-DX, and met the cut-off point for all the IES-R subscales. The remaining 44 patients (95.6%) did not meet the criteria for PTSD diagnosis in the CAPS- DX and did not pass the cut-off point for all the IES-R subscales. Thus, the IES-R was found to have 100% sensi- tivity and specificity for screening of PTSD.

Discussion

The results cross-validate and extend the underlying theo-retical formulation and fundamental psychometric properties of the original IES to the Chinese version of IES-R. The IES-R is found to be reliable with high internal con- sistency. The unique and specific contribution of the IES-R as a measure of psychological impact after a traumatic event is confirmed by its moderate correlation with the GHQ-20 and strong correlation with the PCL.

IES-R is not a diagnostic measure for PTSD because criterion A of the disorder is not assessed, and the items included are not directly translated from the DSM-IV. However, the use of the IES-R for screening of PTSD was supported by the favourable relations between the IES-R and CAPS-DX, and by the satisfactory sensitivity and specificity of the IES-R in detecting PTSD defined by the CAPS-DX.

This study suggests that the 2-factor model for the original IES assumed in Horowitz's stress response theory2 also applies to the Chinese version of the IES-R. The factor structure and subscale correlations of the IES-R indicate 2 related but independent factors. The first factor is represented by symptoms for intrusion and hyperarousal, while the second factor is represented by symptoms for avoidance. Thus, the 2-factor structure is consistent with the presence of either 'overwhelmed' or 'frozen' states after a traumatic experience as predicted by Horowitz's stress response theory. The 2-factor structure is also consistent with the scale struc- ture found in a study examining the Japanese version of the IES-R.12 However, the 2-factor structure is inconsistent with recent findings of the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms, which suggest a hierarchical 4-factor model (comprising 4 first-order factors corresponding to re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal all subsumed by a higher-order general factor).14,15 The inclusion of the hyperarousal items in the IES-R brings the IES up to date with changes in the PTSD criteria and contributes to the understanding of the psychological impact of traumatic events both for empirical study and clinical work. However, more research is needed to establish the dimensional nature of the IES-R subscales with the added hyperarousal items, and to examine whether identified dimensions differ as a function of the trauma experience.

The present study had some limitations. Patients had experienced a recent traumatic event. However, criterion A for PTSD was not assessed for all patients and they were not the same as the pretherapy clinical group that Zilberg et al suggested for the demonstration of independent factor structure.17 Thus, it is still possible that the variance of the measures and independence of the 3 subscales are blurred because most of the patients in the present study were not experiencing post-traumatic stress to a clinical extent. In addi- tion, the number of patients for the examination of the valid- ity of the IES-R was limiting. Among the patients who were interviewed 1 month after the MVA, only 2 were found to meet the diagnostic criteria of PTSD based on the CAPS-DX. Thus, the sensitivity and specificity of the IES-R for the screening of PTSD has not been adequately tested in the study.

In conclusion, the Chinese version of IES-R can be used for the Chinese population as a brief self-report measure, with good reliability and satisfactory validity for assessing traumatic stress responses due to a variety of traumatic events. The psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the IES-R are similar to those of the IES. The IES-R can also offer clinical information consistent with the present diagnostic criteria for PTSD. However, further study with a clinical group to examine the consistency between the IES-R subscales and the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms is needed.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Accident and Emergency Department and Clinical Psychology Department of the Caritas Medical Centre. We would like to thank Mr Tsang Wai Ming, Dr Fung Yiu Wah, Ms Chu Lai Yee, Ms Regina Kwong, Ms Joanna Poon, and Ms Catherina Ng for their contributions to the study.

References

- Horowitz MJ. Stress response syndromes. New York: Jason Aronson; Scale on a sample of American Vietnam veterans. Psychol Rep 1994;

- 75:321-322.

- Horowitz MJ, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979;41:209-218.

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997:399-411.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1980.

- Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:205-209.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Wu KK, Chan KS. The development of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale-Revised (CIES-R). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:94-98.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Proceed- ings of the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 1993, October; San Antonio. San Antonio: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 1993.

- Maercker A. Lifespan psychological aspects of trauma and PTSD: symp- toms and psychosocial impairments. In: Maercker A, Schutzwohl M, Solomon Z, editors. Posttraumatic stress disorder: a lifespan develop- mental perspective. Toronto: Hogrefe & Huber; 1999:7-41.

- Wu KK. Use of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for treating a motor vehicle accident victim suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. HK J Psychiatry 2002;12(2):20-24.

- Wu KK, Chan KS, Ma MT. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depres- sion in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Traum Stress 2005;18:39-42.

- Asukai N, Kato H, Kawamura N, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese-language version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R-J): four studies of different traumatic events. J Nerv Ment Dis 2002;190:175-182.

- Wu KK, Chan KS, Ma MT. Posttraumatic stress after SARS: a three- month follow-up study. Emerg Infect Dis 2005. In press.

- ing DW, Leskin GA, King LA, Weathers FW. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Assess 1998; 10:90-96.Asmundson GJ, Forombach I, McQuaid J, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, Stein MB. Dimensionality of posttraumatic stress symptoms: a confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV symptom clusters and other symptom models. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:203-214.

- Hendrix CC, Jurich AP, Schumm WR. Validation of the Impact of Event

- Zilberg NJ, Weiss DS, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: a cross- validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982;50: 407-414.

- Blake DD, Weather FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Charney DS. Clini- cian-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS-DX): Boston: Boston Veterans' Association Medical Centre: 1995.

- Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. London: NFER Publishing Co; 1978.

- Chan DW. The Chinese general health questionnaire in a psychiatric setting: the development of the Chinese scaled version. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1993;28:124-129.

- Chan DW. The two scaled versions of the Chinese general health questionnaire: a comparative analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol 1995;30:85-91.

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, non-patient edition (SCID-NP) (Version 1.0). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990.

- Blanchard EB, Alexander JJ, Buckley TC, Catherine AF. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist. Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669-673.

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behav Therapist 1990;13:187-188.

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Traumatic Stress 1995;8:75-90. Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ. After the crash: assessment and treatment of motor vehicle accident survivors. 2nd ed. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2004.

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Dis- order Scale. Psychol Assess 1999;11:124-133.