Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2008;18:144-51

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

創傷後壓力症量表在量度道路交通事故華人生還者時之心理測 量特性研究及結構驗證性因素分析

胡潔瑩、陳潔冰、饒方莉

Dr Kitty K Wu, PhD, Department of Clinical Psychology, Caritas Medical Centre, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Sumee K Chan, MSocSc (Clin Psy), Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Ms Venus F Yiu, MSocSc (Clin Psy), Student Affairs Office, the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Clearwater Bay, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Kitty K Wu, Department of Clinical Psychology, Caritas Medical Centre, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 3408 7975; Fax: (852) 2307 5894;

E-mail: wukyk@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 19 October 2007; Accepted: 11 November 2007

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the psychometric properties and factor structure of the Chinese version of the

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist.

Participants and Methods: A total of 481 survivors of road traffic accidents completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, Impact of Event Scale–Revised, and General Health Questionnaire 1 week after a road traffic accident. Their responses were studied to investigate the factor structure and validity of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist. To examine the diagnostic utility of the Checklist, an independent sample of 45 road traffic accident survivors completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist and the Clinician-administered Post-traumatic Disorder Scale 1 month after their road traffic accidents.

Results: A hierarchical 4-factor model was identified as providing the best account of the data for the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist. The diagnostic efficiency of the mixed scoring criteria, using a minimum symptom score of 4 with either a total score of 44 or 50, was confirmed as a means of screening for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Conclusions: The Chinese version of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist was found to have satisfactory reliability and validity.

Key words: Accidents, traffic; Life change events; Questionnaires; Stress disorders, post-traumatic

摘要

目的:探討創傷後壓力症量表(中文版)的心理測量學特性及因素分析。

參與者與方法:因道路交通事故而到急症室求診之481名成人生還者參予是項研究。研究探討了 這組參加者在意外後一星期所填寫心理量表之結果,這些量表包括創傷後壓力症量表、事件影 響測量表(修訂版),以及一般健康問卷。所得的結果用來探討創傷後壓力症量表的因子結構和效度。為研究此量表的診斷功效,另邀請45名獨立的道路交通事故生還者,於意外後一個月填寫創傷後壓力症量表和接受由臨床專業人員評估的DSM-IV創傷後壓力症量表 。

結果:根據結構驗證性因素分析的結果,4個分層因子的模式能為所收集的數據提供最佳的解 釋。使用個別項目得分為4分,並總得分為44分或50分的混合計分標準的診斷效率,被確認為創傷後壓力症的篩選標準。

結論:創傷後壓力症量表(中文版)有滿意的信度及效度。

關鍵詞:交通事故、負性生活事件、問卷、創傷後壓力症候群

Introduction

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV),1 the prevalence of acute stress disorder in individuals exposed to trauma ranges from 14 to 33%. In the adult population the lifetime prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) found in community-based studies is approximately 8%. However, there are few psychometrically sound Chinese language PTSD-related assessment instruments for clinical and research use. Although the Chinese version of the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R) has been proven a useful means of examining traumatic stress, the items included do not bear a direct reference to the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV.2-6

The PTSD Checklist (PCL)7 is a 17-item, self- reported rating scale instrument that parallels DSM-IV’s diagnostic criteria B, C, and D for PTSD. Thus, the PCL may yield information that has greater predictive validity on a diagnostic level than the IES-R. The PCL’s structure may also enable researchers to draw more precise comparisons with data derived from PTSD-relevant interviews such as the Clinician-administered PTSD Scale (CAPS).8 The PCL’s diagnostic sensitivities and specificities in different languages have been demonstrated. This includes the English version,7,9,10 French version,11 and Spanish version.12 As it takes only a short period, roughly 5 minutes, to administer the PCL, it compares favourably with the 40 to 60 minutes needed for diagnostic interviews (e.g. CAPS), making the PCL a good candidate as a screening tool for PTSD. There is a need for PTSD-related assessment instruments in Chinese, so this study was conducted to investigate the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the PCL and to provide preliminary results for guiding future use of the PCL as a valid and reliable PTSD assessment instrument in Chinese.

This study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the PCL when applied to survivors of road traffic accidents (RTAs) attending accident and emergency (A&E) services. Data collected from 481 respondents 1 week after experiencing a RTA were used to study the internal consistency, reliability, and factor structure of the PCL. Given the personal impact, nature and recency of the event, data from RTA survivors at this point should enable us to understand the psychometric properties of the PCL. The concurrent validity of the PCL was examined by studying its relationship with self-reported measures of general psychological distress and posttraumatic stress, respectively. To examine the diagnostic utility of the PCL in PTSD, the results of 4 different PCL scoring criteria suggested in previous research7,9 were compared with the results of the Clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS- DX),13 a clinician-administered structured interview used for diagnosing PTSD, given to an independent sample of 45 RTA survivors 1 to 2 months after the RTA.

Methods

Participants

Survivors of RTA participating in the study were recruited from the A&E Department of the Caritas Medical Centre, Hong Kong, between October 2003 and July 2005. The inclusion criteria were: (a) requiring medical attention in the A&E due to an injury caused by a RTA, (b) being 18 years old or above, (c) having the ability to read and write Chinese. Participants were required to complete the Chinese versions of the PCL, IES-R5,6 and General Health Questionnaire–20 (GHQ-20)14,15 1 week after the RTA. These questionnaires were posted to the participants with return envelopes provided. The hospital’s research ethics committee approved the study.

Altogether 308 men and 173 women, aged 18 to 98 (mean, 41.4; standard deviation [SD], 16.5) years consented to and participated in the study. The 481 participants represented 26.3% of all RTA survivors who attended the A&E services of the hospital within the period studied. Physicians in the A&E Department rated the severity of all the respondents’ physical symptoms: 393 (81.7%) were rated as “Mild: operation or plaster of Paris (POP) not required; Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 15”, 3 (0.6%) were rated as “Moderate: operation or POP required; GCS of 15”, and 85 (17.7%) were rated as “Severe: hospital admission required; GCS of 14 or 15”. No participant had injuries rated as “Life Threatening: hospital admission required; GCS of 13 or below”. Study participants were younger than non-participants (mean, 42.3; SD, 17.2 years, t = 4.18, p < 0.001). Gender and the severity of physical injury as rated in the A&E were not related to participation in the study (p > 0.05).

To examine the diagnostic utility of the PCL for PTSD, an independent sample of 45 RTA survivors was recruited for the second phase of the study. As the duration of distress must last for more than 1 month for a diagnosis of PTSD, the CAPS-DX was conducted for these participants at least 1 month after the RTA. The mode and criteria of recruitment for these participants were the same as those used in the first phase of the study. Participants had to complete the PCL before the CAPS-DX was conducted. The average time lapse between the RTA and the interview was 57.1 (SD, 19.5) days after the RTA. Among these participants, there were 31 (68.9%) men and 14 (31.1%) women, aged 18 to 78 (mean, 39.0; SD, 13.4 years). The severity of their physical injuries was also rated: 34 (75.6%) were rated as “Mild: operation or POP not required; GCS of 15”, 1 (2.2%) was rated as “Moderate: operation or POP required; GCS of 15”, 10 (22.2%) were rated as “Severe: hospital admission required; GCS of 14 or 15”. There were no significant differences between these 1-month respondents and those who participated as 1-week respondents in terms of age, gender, severity of physical injury, and PCL scores 1 week after the RTA.

Instruments

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

The PCL is a self-reported inventory for assessing the 17 symptoms of PTSD corresponding to the 3 DSM-IV symptom clusters of re-experiencing (5 items), avoidance / numbing (7 items), and hyperarousal (5 items).7 The non- military version, that can be referenced to a specific traumatic event and can usually be completed by respondents within 10 minutes, was used in the study. The degree of distress for each item is rated on a 5-point scale (1 to 5), ranging from the absence of a symptom to maximum symptomatology. For this study, 3 subscale scores were computed by adding the scores of items belonging to the same DSM-IV cluster. The total score of the original study was also computed by adding the 17 items, so that possible total scores range from 17 to 85. In Vietnam War veterans, a cut-off of 50 on the PCL was found to be a good predictor of PTSD.7

Weathers et al7 found that the PCL has a high test-retest reliability (r = 0.9) and validity as indicated by a kappa of 0.6 for the diagnosis of PTSD from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R.16 The PCL has been examined in cross-validation studies on victims of different types of trauma (e.g. RTA and sexual assault) using diagnoses and scores from the CAPS.9

The comparability of the Chinese PCL and the original English PCL has been validated by stringent back- translation procedures used for the present study. Taking the differences in language and culture into consideration, a bilingual clinical psychologist first translated the PCL aiming to retain the meaning of each item in the Chinese version. An independent bilingual clinical psychologist back-translated this into English for content comparison. The content of the final Chinese PCL was further verified by back-translation procedures until the meaning of each item matched with the original item.

Impact of Event Scale–Revised

The IES-R17 is a self-reported measure for capturing the level of symptomatic responses to a specific traumatic stressor experienced during the past week. The degree of distress caused by each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from the absence of a symptom (scoring 0) to maximum symptomatology (scoring 4). There are 3 subscales (i.e. Intrusion, Avoidance, and Hyperarousal). Subscale scores are equal to the mean score of the non-missing items for the specific subscale.

The IES-R subscales have demonstrated internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = 0.79 to 0.91, and test- retest reliability coefficients ranging from 0.51 to 0.94.17 The Chinese version of the IES-R5,6 was found to have internal consistency and scale equivalence comparable to the original English version.

General Health Questionnaire–20

The GHQ-2014,15 is a widely used instrument spanning a range of items indicative of psychological distress. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of GHQ- 20 have been verified in local studies.18,19 The present study used a simple Likert method (0 to 3) of scoring. The Chinese version of the GHQ-20 was used in this study as an alternative measure of general psychological distress to examine the concurrent validity of the Chinese PCL.

Clinician-administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition)

The CAPS8,20 is a widely used structured interview for assessing PTSD. According to a review of 10 years of research, CAPS has excellent reliability, yielding consistent scores across items, raters, and testing occasions.21 It has good convergent and discriminant validity, and sensitivity to clinical change. In the present study, the CAPS-DX,13 a revised version of the CAPS developed after the 1994 publication of the DSM-IV, was used. In previous studies of RTA survivors, test-retest reliabilities were reported to be 0.90 to 0.98, and the internal consistency was 0.94.22

The CAPS-DX includes a life-event checklist for examining Criterion A of PTSD. For each of the 17 symptoms of PTSD, CAPS-DX assesses both the frequency of occurrence and the severity of symptoms at their worst over the past month on a 5-point scale. For frequency of occurrence, each item is rated from never (scoring 0) to daily or almost every day (scoring 4). For symptom severity, each item is rated from none (scoring 0) to extreme (scoring 4). Thus, each item can have a score of 0 to 8. Specific scores for Criteria B, C, and D, can be found by adding up the item scores belonging to the specific criteria.

In the present study, an empirically derived rule for making a diagnosis of PTSD was adopted.23 According to this method, a PTSD symptom was considered present if the frequency of the corresponding CAPS-DX item was rated as 1 or higher and the intensity was rated as 2 or higher. The severity score of an item is equal to the sum of the frequency and intensity scores. To ensure both a significant overall level of PTSD symptom severity and a distribution of symptoms corresponding to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, a total severity score of 65 or higher was required for making a diagnosis of PTSD.

The CAPS-DX was translated into Chinese using back-translation procedures in a previous study. The inter- rater reliability for judging a criterion used for individual symptom clusters was 0.93, and that for making the diagnosis of PTSD based on DSM-IV criteria was 1.0 according to that study.24 The CAPS-DX assessors were blinded to the PCL results when they conducted and rated the CAPS-DX.

Results

Psychometric Properties of the Chinese Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

Reliability of the Chinese Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

Abbreviated PCL item contents, DSM-IV symptom cluster membership, and item-level descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. The descriptive statistics for the PCL subscale and total scores are shown in Table 2. The internal consistency of the PCL subscale and total scores examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients found that the subscales were reliable. The results of these analyses produced the following coefficients: Re-experiencing (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), Avoidance (Cronbach’s α = 0.79), Hyperarousal (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), and Total (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

The analyses of the split-half reliability of the PCL yielded the following Guttman split-half coefficients: Re-experiencing (r = 0.88), Avoidance (r = 0.82), Hyperarousal (r = 0.86), and Total (r = 0.93). The corrected item-total correlations produced the following ranges of coefficients: Re-experiencing (rs = 0.75 to 0.84), Avoidance (rs = 0.61 to 0.79), Hyperarousal (rs = 0.73 to 0.84), and Total (rs = 0.64 to 0.85). These data suggest that the internal consistency of the 3 subscales and the total score was satisfactory and each of the individual items was consistent with the remaining items.

Of the 481 participants, 265 (55.1%) agreed to retake the Chinese PCL 1 month after the RTA. Their data were used to examine the test-retest reliability of the PCL, yielding the following correlation coefficients: Re-experiencing (r = 0.76), Avoidance (r = 0.80), Hyperarousal (r = 0.82), and Total (r = 0.84). No significant differences were found between these respondents and those who did not respond after 1 month in age, gender, severity of physical injury and their PCL scores 1 week after the RTA.

Factor Structure of the Chinese Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the factor structure of the PCL. The Structural Equation Modelling, using EQS for Windows Version 6.125 in which the maximum likelihood method was used to investigate the overall fit of the models to the corresponding observed variance and covariance matrices.

Model fit was assessed in several ways. The goodness- of-fit indices, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Non- normed Fit Index (NNFI), were examined. The CFI ranges between 0 and 1, with values greater than 0.90 indicating a good fit. 26 The RMSEA is a measure of the discrepancy between the model and the data per degree of freedom; RMSEA values which are below 0.08 indicate a satisfactory fit.27 The NNFI measures the relative improvement in fit by comparing a target model with a baseline model with respect to the degree of freedom. It ranges from 0 to 1, with values greater than 0.90 implying a good fit.28

According to the symptom clusters of PTSD stated in the DSM-IV, a hierarchical 3-factor structure for the PCL was examined. The results demonstrated a satisfactory fit of the hierarchical 3-factor structure of the Chinese PCL in the current sample, which included re-experiencing, avoidance and hyperarousal (χ2 (116) = 675.01; CFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.10; NNFI = 0.91). Other research findings suggested that the factor structure of PCL, which indicates the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms, was best explained by a hierarchical 4-factor model (i.e. comprising 4 first-order factors corresponding to re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal all subsumed by a higher-order general factor).29,30 For model comparison, the hierarchical 4- factor model was examined and demonstrated a satisfactory goodness-of-fit (χ2 (115) = 630.40; CFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.097; NNFI = 0 .91). A Chi-square difference test was carried out to evaluate which model gives a better fit. The Chi-square difference test revealed that the hierarchical 4- factor model was significantly better than the hierarchical 3-factor model (χ2 difference = 44.61, df = 1, p < 0.05). The findings for model comparison are shown in Table 3. Based on the Chi-square data, scores on various fit indices, the hierarchical 4-factor model was identified as providing the best account of the data. The model structure of the 2 models is shown in Figure 1. The hierarchical four-factor model is shown in Figure 2. These findings are consistent with the existing literature on theoretical and clinical presentations of PTSD.29,30 The factor loadings are significant at the p < 0.05 level and are presented in Table 1.

Correlates of the Chinese Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

Severity of Physical Injury, Age, and Gender

The severity of physical injury ratings correlated significantly with the PCL Re-experiencing (r = 0.16), Avoidance (r = 0.16), Total (r = 0.18) [p < 0.001], and Hyperarousal scores (r = 0.18) [p < 0.01], indicating that the severity of PTSD symptoms as measured by the PCL were related to the severity of physical injuries sustained during the RTA. The relationships between PCL scores, age and gender were not significant.

Impact of Event Scale–Revised and General Health Questionnaire–20

To examine the convergent validity of the Chinese PCL as a measure of psychological distress, Pearson correlations between the total scores from the GHQ-20 and the PCL subscale and total scores were studied. As presented in Table 4, the correlation coefficients indicated that they were moderately related, showing that the PCL contributed information that was not captured by the GHQ-20. To determine the utility of the Chinese version of the PCL as a specific measure for post-traumatic stress, the Pearson correlations between the subscale and total scores of the PCL and IES-R were examined. As shown in Table 4, the correlation coefficients indicated moderate-to-strong relationships between the 2 measures.

Clinician-administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition)

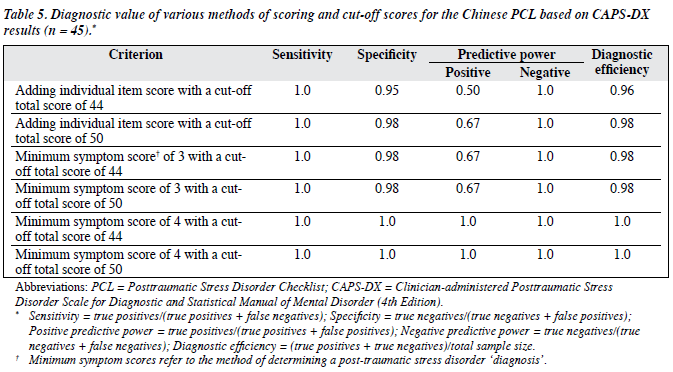

To examine the discriminant validity of the Chinese PCL as a screening measure for PTSD, the relationships between the PCL and the CAPS-DX conducted 1 month after the RTA were studied. Pearson correlations between the PCL subscales and CAPS-DX criterion scores were examined and are presented in Table 4. The diagnostic utilities of 6 different scoring methods suggested in previous studies were examined. The diagnostic value of various methods of scoring and cut-off scores examined are presented in Table 5.

Using the CAPS-DX results as the ‘gold standard’, the diagnostic value of the PCL with a total score of 50 as the cut-off for PTSD screening, as suggested by Weathers et al7 was examined. According to the CAPS-DX, 2 (4.4%) of our study participants were classified as having PTSD. These 2 participants also had PCL Total scores above 50. However, 1 false positive was identified when the cut-off was based on a PCL Total score of 50. Thus, based on the cut-off suggested for Vietnam veterans in the original study,7 the PCL has 1.0 sensitivity and 0.98 specificity in our sample. If the cut-off was based on a total score of 44, as suggested by other researchers,9 we would have found 2 false positives and the specificity would have dropped to 0.95.

One limitation of the above 2 criteria is that the cut-off was based on the PCL Total score and does not necessarily indicate endorsement of symptoms in a pattern fitting the DSM-IV criteria. It is also not clear what minimum score (e.g. 2, 3, 4, or 5) should be used to define an item meeting PTSD criteria. According to a more recent study on the PCL,10 the best values for achieving diagnostic efficiency matching the cut-off scores recommended by previous studies7,9 come via the mixed scoring criteria. This involves using either a cut-off Total score of 44 or 50 with a minimum score of 3 or 4 for individual items needed to count that symptom toward meeting Criteria B, C, and D. For example, besides meeting the cut-off Total score of 44 or 50, when a minimum symptom score of 3 is used then at least 1 of the 5 Re-experiencing items; 3 of the 7 Avoidance items; 2 of the 5 Hyperarousal items need to have a minimum score of 3 to meet Criteria B, C, and D, respectively. Thus, we sought to determine how these 4 scoring criteria (a minimum symptom score of 3 or 4 is needed for endorsement of a particular item with either a Total cut-off of 44 or 50) differentially predicted a diagnosis of PTSD.

As shown in Table 5, the PCL sensitivity remained at 1.0 for the 4 different mixed scoring criteria (i.e. the 2 cases classified as having PTSD according to the CAPS-DX were correctly identified). However, 1 false-positive case was identified when a minimum symptom score of 3 was adopted. There were no false positives when the minimum symptom score of 4 with either a Total score of 44 or 50 was adopted.

Discussion

This study has found that the Chinese version of the PCL is reliable and has high internal consistency. The specific contribution of the PCL as a measure of psychological impact after traumatic event is supported by its moderate correlation with the GHQ-20 and strong correlation with most of the IES-R subscales. The PCL is not a diagnostic measure for PTSD because Criterion A of the disorder is not assessed. Use of the CAPS-DX as a means of detecting PTSD in this study offers preliminary support for the Chinese PCL as a screening measure for PTSD. As found by a previous study,10 the use of the mixed scoring criteria with a minimum symptom score of 4 for individual items and a Total score of 44 or 50 for the cut-off has higher diagnostic efficiency than using a Total score of 44 or 50 as the cut-off alone.

Our findings suggest that the Chinese PCL can be used for the assessment of post-traumatic stress and evaluation of treatment outcomes. The data collected in this study can also serve as a baseline for comparison with clinical samples of RTA victims and as a reference for victims of other traumatic events, particularly in Chinese populations. With the accumulation of data from different samples, clinicians serving Chinese populations can also utilise the PCL as a screening tool for psychological distress in victims of life-threatening critical incidents, and as a measure for evaluating treatment outcomes.

Though the dimensionality of post-traumatic stress symptoms is beyond the scope of the present study, the hierarchical 4-factor model identified was inconsistent with the 3 symptom clusters of DSM-IV, but replicated recent research that used the PCL to examine the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms. These findings suggest that the factor structure of the PCL, which indicates that the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms is best explained by a hierarchical 4-factor model (i.e. comprising 4 first-order factors corresponding to re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal, all subsumed by a higher-order general factor).29,30 Thus, more research is needed to establish the dimensional nature of PTSD; to evaluate the symptom clusters adopted in the DSM-IV; and to examine whether identified dimensions differ as a function of the traumatic experience. A validated Chinese version of the PCL will help with examination of the generalisability of these identified dimensions across cultures.

All of our study respondents experienced a recent traumatic event, however, criterion A for PTSD was not assessed in all respondents. They did not conform to the pre- therapy clinical sample that Zilberg et al31 have suggested for the demonstration of independent factor structure. Thus, it is still possible that the variance of the measures and independence of the 3 subscales corresponding to the DSM-IV symptom clusters are blurred because most respondents in the present study were not experiencing clinical post- traumatic stress. The study participants were younger than those who declined to participate, a factor that could affect the generalisability of our results. The number of participants who underwent a CAPS-DX examination also limited our study; of participants interviewed 1 month after the RTA, only 2 met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD based on the CAPS-DX. Thus, the sensitivity and specificity of the Chinese PCL for the screening of PTSD has not been adequately tested by this study, something that might also limit its generalisability.

The psychometric properties of the Chinese version of PCL were supported. The PCL can offer information consistent with the DSM-IV’s diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Further investigations using a clinical sample to examine the discriminant validity and consistency between the PCL subscales and the dimensionality of PTSD symptoms are suggested.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Clinical Psychology Department and the A&E Department of the Caritas Medical Centre. We would like to thank Dr Yiu-wah Fung, Mr Wai-ming Tsang, Ms Lai-yee Chu, and Ms Catherina Ng for their contributions to the study.

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Wu KK, Cheung MW. Posttraumatic stress after motor vehicle accident: a six-month follow-up study utilizing latent growth modeling. J Trauma Stress 2006;19:923-36. Erratum in: J Trauma Stress 2007;20:371.

- Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Trauma Stress 2005;18:39-42.

- Wu KK, Chan SK, Ma TM. Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:1297-300.

- Wu KK, Chan KS. The development of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale —Revised (CIES-R). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:94-8.

- Wu KK, Chan KS. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R). HK J Psychiatry 2004;14:2-8.

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Proceedings of the 9th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; 1993 October; San Antonio, CA; 1993.

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney D, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behav Ther 1990;13:187-8.

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34:669-73.

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. J Trauma Stress 2003;16:495-502.

- Ventureyra VA, Yao SN, Cottraux J, Note I, De Mey-Guillard C. The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychother Psychosom 2002;71:47-53.

- Marshall GN. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Checklist: factor structure and English-Spanish measurement invariance. J Trauma Stress 2004;17:223-30.

- Blake DD, Weather FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Charney DS. Clinician-administered PTSD Scale for DSM-IV (CAPS-DX): Boston: National Centre for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division, Boston VA Medical Centre; 1995.

- Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1972.

- Goldberg DP. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. London: NFER Publishing Co; 1978.

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First MB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, non-patient edition (SCID-NP) (Version 1.0). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1990.

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale – Revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997:399-411.

- Chan DW. The Chinese General Health Questionnaire in a psychiatric setting: the development of the Chinese scaled version. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1993;28:124-9.

- Chan DW. The two scaled versions of the Chinese General Health Questionnaire: a comparative analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995;30:85-91.

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress 1995;8:75-90.

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JR. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: a review of the first ten years of research. Depress Anxiety 2001;13:132-56.

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ. After the crash: assessment and treatment of motor vehicle accident survivors. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2004.

- Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM. Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychol Assess 1999;11:124-33.

- Chu LY. Coping, appraisal and post-traumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident [thesis]. Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong; 2004.

- EQS for Windows (Version 6.1) [Computer software] [program]. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 2003.

- Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994.

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993:136-62.

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 1980;88:588-606.

- Asmundson GJ, Frombach I, McQuaid J, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, Stein MB. Dimensionality of posttraumatic stress symptoms: a confirmatory factor analysis of DSM-IV symptom clusters and other symptom models. Behav Res Ther 2000;38:203-14.

- King DW, Leskin GA, King LA, Weathers FW. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: evidence for the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Assess 1998;10:90-6.

- Zilberg NJ, Weiss DS, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: a cross- validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1982;50:407-14.