Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2006;16:71-75

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

YT Xiang, YZ Weng, CM Leung, WK Tang, GS Ungvari

Dr Yu-Tao Xiang, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China and Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Professor Yong-Zhen Weng, MD, Beijing Anding Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

Dr Chi-Ming Leung, MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Associate Professor Wai-Kwong Tang, MD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Professor Gabor S. Ungvari, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Yu-Tao Xiang, Department of Psychiatry, Shatin Hospital, Shatin, New Territories Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2636 7748; Fax: (852) 2647 5321;

E-mail: xyutly@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 17 October 2006; Accepted: 28 November 2006

Abstract

Objective: To date, few studies have investigated depot antipsychotic medication in Chinese patients with schizophrenia in general and outpatients with schizophrenia in particular. This study examined the frequency, and sociodemographic and clinical correlates of depot anti- psychotic medication in Hong Kong.

Patients and Methods: 267 clinically stable outpatients with schizophrenia were randomly selected and interviewed in Hong Kong using standardised assessment instruments. Data on pre- scription patterns of all psychotropic drugs were collected at the time of the diagnostic interview. Results: Depot antipsychotic treatment was employed in 36.7% (n = 98) of the sample. Patients on depot antipsychotics were older, had longer duration of illness and more psychiatric hospitalisations and better scores on the social domain of quality of life. They were more likely to receive antipsychotic polypharmacy and anticholinergic drugs and to be on priority follow-up status and on conditional discharge, and less likely to receive clozapine. In multiple logistic regres- sion analysis, the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy, history of suicide attempts, educational level and being on conditional discharge all significantly predicted the use of depot antipsychotics.

Conclusion: The use of depot antipsychotics appeared to be independent of the severity of psychotic symptoms. It is a cause for concern that depot antipsychotic therapy was associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy because the very advantage of depot antipsychotics is lost in clinically stable outpatients. It seems that clinicians are more reluctant to prescribe depot anti- psychotic for younger patients than older ones. Regular surveys of prescribing practices with the aim of more rational use of depot antipsychotics are warranted.

Key words: Antipsychotic agents, Delayed-action preparations, Drug utilization, Outpatients, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Depot antipsychotic drugs (DA) have been widely used in clinical practice since the 1960s in an attempt to reduce relapse rate and improve the prognosis of psychoses, particularly schizophrenia, in the long term.1 Their prescrip- tion patterns have been repeatedly reported in western countries,2,3 but there are few studies examining the utilisation of DA for Chinese schizophrenia patients in general and outpatients with schizophrenia in particular. This omission is all the more important because outpatients account for the majority of the patient population suffering from schizophrenia in mainland China.4 Furthermore, studies conducted in western countries found that DA use was associated with improved quality of life (QOL).5,6 The aims of this study were to determine the frequency, and sociodemographic and clinical correlates of use of DA and compare QOL between DA-treated and non-DA-treated patients in Hong Kong.

Patients and Methods

Settings and Subjects

The study was conducted in Hong Kong between January 2005 and April 2006. Subjects were selected by computer- generated random numbers from patients diagnosed with schizophrenia attending the Li Ka Shing Psychiatric Out- patient Clinic of Prince of Wales Hospital, which has a catch- ment area with a population of approximately 800,000.

Patients who met the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study: (1) diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition7; (2) age 18 to 60 years; (3) length of illness ³ 5 years; and (4) out- patients having been clinically stable for at least 3 months before recruitment. Following a recent definition,8 clinical stability was defined as either no change in the medication or other forms of treatment or an increase in the dose of drug(s) by no more than 50% over the past 3 months. Exclu- sion criteria were: (1) history of or ongoing major chronic medical or neurological condition(s); and (2) past or current significant drug/alcohol abuse other than nicotine. The study was designed and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.9 The study protocol was approved by the Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research Ethics Committee in Hong Kong. All participants signed a consent form.

Data Collection

Data on sociodemographic variables and the use of psycho- tropic drugs were collected at the time of a diagnostic interview. Psychotic symptoms were assessed by use of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).10 For this study, the following three mean BPRS scores were used: (1) positive symptoms of conceptual disorganisation, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behaviour, and unusual thought content; (2) negative symptoms of emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, blunted affect and disorientation; and (3) symp- toms of anxiety and tension. Extrapyramidal side effects were measured by the Simpson and Angus Scale of Extra- pyramidal Symptoms 11 and the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.12 For the sake of brevity, the sum scores of these scales were entered in the statistical analysis. The 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale13 was used to evaluate the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. QOL was assessed by use of the Hong Kong version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Schedule-Brief,14 that covers four domains: physical and psychological health, social relationships and environmental factors. Patients assess their satisfaction of each item during the past two weeks on a 5-point scale (from 1 = "very dissatisfied" to 5 = "very satisfied"). Doses of antipsychotic drugs were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents.15

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons between the DA and non-DA groups with regard to sociodemographic and clinical characteris- tics and QOL were performed by independent samples t test, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests as appropriate and applicable. To compare the QOL and control the potential confounding influence of other variables between the DA and non-DA cohorts, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was carried out. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for relevant covariates and to determine the predictors of prescription of DA. The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to check the normality of distributions for continuous vari- ables. The level of significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

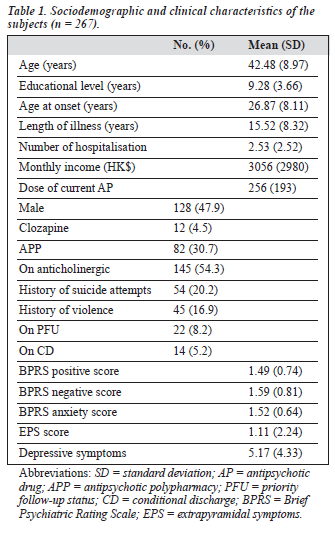

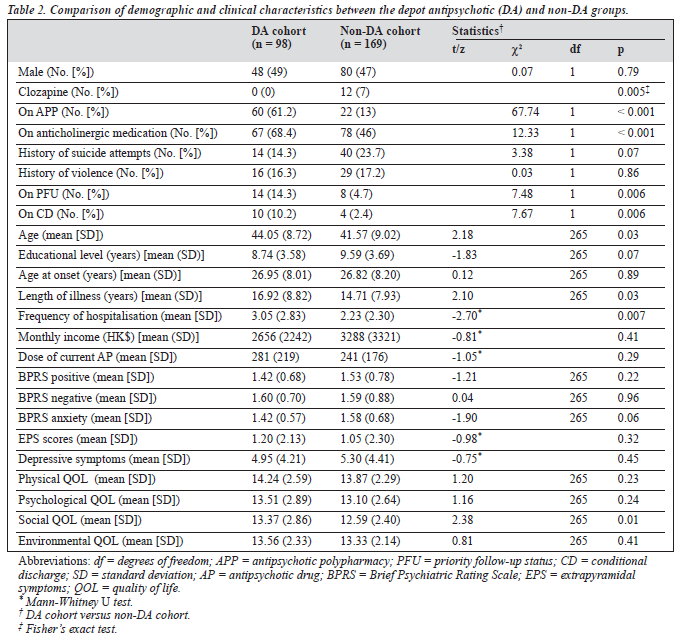

310 patients were approached to take part in the study, of whom 43 refused participation. There was no significant difference between the study subjects and those patients who refused to participate with regard to age, gender, age at onset and length of illness. Table 1 shows the basic socio- demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects. Ninety eight (36.7%) of the 267 subjects received DA. Tables 2 and 3 show the variables which were significantly associ- ated with the use of DA.

Except for the social domain, there was no difference with respect to QOL between the DA and non-DA groups. The significant difference in social QOL domain between the two samples remained (F [1, 257] = 5.38, p = 0.021) after controlling for the effect of age, length of illness, frequency of hospitalisation, use of clozapine, antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP) and anticholinergic drugs, priority follow-up status and being on conditional discharge in ANCOVA.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate the use of DA in Chinese schizophrenia outpatients. The frequency of DA for the whole sample was 36.7%, a figure which is in accordance with the findings of previous studies.2,3,16 Citrome et al2 found that 12-39% of schizophrenia inpatients were prescribed DA in psychi- atric hospitals in the United States. Covell et al3 reported that 50% of community-dwelling American outpatients received DA. Sim et al16 found that 4.7-75.0% of schizo- phrenia patients were on DA in the East Asian region. Surprisingly, only 4.7% of patients in Hong Kong received DA in that study. The major reason could be that the Hong Kong sample was recruited from long-term inpatient units where DA was less likely to be used due to its inflex- ibility of administration.17

A complex web of factors, including prescribing tradi- tions, sociocultural factors, health insurance and availability and cost of the drugs all contribute to the prescription of DA. For example, Sim et al16 reported that DA were relatively expensive in Korea and Japan in comparison with other East Asian countries. In contrast, DA were one of the cheapest antipsychotic options in Hong Kong. In this study, clozapine was less frequently prescribed in the DA group, a practice which is in keeping with current recommendations: to date there is no strong evidence suggesting an advantage of combination of clozapine with other antipsychotics.18 The association between the use of DA and APP could be partially attributed to the lack of flexibility of DA in dosing.17 While it is justified to temporarily augment DA by oral drugs,19 the prescription of combinations of DA and oral antipsychotics is hardly justified in clinically stable outpatients. As some authors suggested,20 the higher rate of APP in the DA group may also be related to a general principle of traditional Chinese medicine postulating that the best prescription should contain a combination of various ingredients.

Strong pharmacological evidence for APP is still lacking.20 A study investigating psychiatrists' attitude toward mainten- ance medication for schizophrenia revealed that 38% of UK psychiatrists thought that DA treatment was associated with increased extrapyramidal symptoms.21 However, to date, there is no compelling evidence that DA are associated with a significantly higher incidence of extrapyramidal symp- toms than oral drugs.22,23 To some extent this notion may well be applicable to Hong Kong since Hong Kong psy- chiatry is close to the British model in terms of its guiding principles, training and types of service delivery.24 Therefore, the higher rate of anticholinergic drug pre-scription in the DA group could reflect an anticipated high occurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms.

The association of DA with advanced age, longer dura- tion of illness and higher frequency of hospitalisation indi- cated that these factors could increase the likelihood of DA use in clinical practice, as in other East Asian countries.16 The advantages of DA are ensured compliance, consistent treatment, elimination of bioavailability related to absorp- tion and first-pass metabolism, achievement of stable plasma concentrations of the antipsychotic drug and reduced rates of relapse and hospitalisation.17 These benefits could explain the association of DA, priority follow-up status and being on conditional discharge. Compared with oral administration, it is easier and safer to deliver the lowest effective dose using DA, thereby decreasing the likeli- hood of adverse effects.25 Knapp et al26 found that DA may lower the costs of treatment and improve cost-effectiveness. Accordingly, Glazer and Kane23 argued that DA remained an underutilised treatment option and would merit wider use. Furthermore, the above-mentioned advantages of DA could be expected to contribute to improved QOL. In fact, the score for the social environment domain of QOL was higher in the DA group in line with earlier reports.6 However, at this point these considerations are somewhat speculative and further studies are warranted to verify these results in Chinese patients.

The major strength of this study is the fairly large, ran- domly selected, ethnically homogenous sample. However, the results should be interpreted with caution and several methodological shortcomings in mind. First, the results are applicable only to clinically stable schizophrenia outpatients living in the community. Second, the study was cross-sectional and therefore the causality of relationships is rather tentative. Third, the definition of clinical stability for schizophrenia pa- tients applied in this study was relatively wide. Fourth, the reasons for the use of APP could not be ascertained from the case notes. Finally, the conversion of different antipsychotics into chlorpormazine equivalents is a rough approximation at best and lacks sound scientific basis, particularly for atypical antipsychotics.27

References

- Walburn J, Gray R, Gournay K, Quraishi S, David AS. Systematic re- view of patient and nurse attitudes to depot antipsychotic medication. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:300-7.

- Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of depot neuroleptic medication in psychiatric inpatients. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1996;32: 321-6.

- Covell NH, Jackson CT, Evans AC, Essock SM. Antipsychotic pre- scribing practices in Connecticut's public mental health system: rates of changing medications and prescribing styles. Schizophr Bull. 2002; 28:17-29.

- Weng YZ, Xu MJ, Li DL, Guo FY, Huang Q, Fu T. Assessment of expressed emotion in family members of schizophrenic patients in Beijing. Modern Rehabilitation. 2001;5:39-42.

- McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long- acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 5): 15-8.

- Larsen EB, Gerlach J. Subjective experience of treatment, side- effects, mental state and quality of life in chronic schizophrenic out- patients treated with depot neuroleptics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996; 93:381-8.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Lobana A, Mattoo SK, Basu D, Gupta N. Quality of life in schizophre- nia in India: comparison of three approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:51-5.

- Schuklenk U. Helsinki Declaration revisions. Issues Med Ethics. 2001; 9:29.

- Overall JE, Beller SA. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) in geropsychiatric research: I. Factor structure on an inpatient unit. J Gerontol. 1984;39:187-93.

- Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11-9.

- Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672-6.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62.

- WHO. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL- BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551-8.

- Sim K, Su A, Leong JY, et al. High dose antipsychotic use in schizophrenia: findings of the REAP (research on east Asia psychotro- pic prescriptions) study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37:175-9.

- Sim K, Su A, Ungvari GS, et al. Depot antipsychotic use in schizo- 33:83-9. phrenia: an East Asian perspective. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19: 103-9.

- Barnes TR, Curson DA. Long-term depot antipsychotics. A risk- benefit assessment. Drug Saf. 1994;10:464-79.

- Remington G, Saha A, Chong SA, Shammi C. Augmentation strategies in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2005;19:843-72.

- Ungvari GS, Chung YG, Chee YK, Fung-Shing N, Kwong TW, Chiu HF. The pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia in Chinese patients: a comparison of prescription patterns between 1996 and 1999. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:437-44.

- Binder RL, Kazamatsuri H, Nishimura T, McNiel DE. Tardive dyski- nesia and neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism in Japan. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1494-6.

- Patel MX, Nikolaou V, David AS. Psychiatrists' attitudes to mainte- nance medication for patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2003;

- Kane JM, Aguglia E, Altamura AC, et al. Guidelines for depot anti- psychotic treatment in schizophrenia. European Neuropsychopharmaco- logy Consensus Conference in Siena, Italy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1998;8:55-66.

- Glazer WM, Kane JM. Depot neuroleptic therapy: an underutilized treat- ment option. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53:426-33.

- Ungvari GS, Chiu HF. The state of psychiatry in Hong Kong: a bird's eye view. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:5-9.

- Gerlach J. Depot neuroleptics in relapse prevention: advantages and disadvantages. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;9(Suppl. 5):17-20.

- Knapp M, Ilson S, David A. Depot antipsychotic preparations in schizophrenia: the state of the economic evidence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:135-40.

- Taylor D, Paton C, Kerwin R. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines. London: Martin Dunitz; 2003.