East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2021;31:9-12 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2019

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Michael CC Kuo, PhD, OTR, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Tung Wah College, Hong Kong SAR, China

King-Tung Au, BSc(OT), Department of Occupational Therapy, The Society for the Relief of Disabled Children, Hong Kong SAR, China

Yuen-Sum Li, BSc(OT), Elderly Service, The Salvation Army, Hong Kong SAR, China

Kai-Chun Siu, BSc(OT), Department of Occupational Therapy, United Christian Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Yuen-Kiu Wong, BSc(OT), Department of Occupational Therapy, Kowloon Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China

Armstrong TS Chiu, BSc(OT), Hong Kong Society for the Blind, Hong Kong SAR, China

King Yeung, MSSM, BSW, Hong Kong Society for the Blind, Hong Kong SAR, China

Address for correspondence: Dr Michael Chih-Chien Kuo, Tung Wah College, School of Medical and Health Sciences, 98 Shantung Street, Mongkok, Kowloon, Hong Kong.

Email: michaelkuo@twc.edu.hk

Submitted: 19 March 2020; Accepted: 16 December 2020

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Dementia Quality of Life Measure - Proxy (C-DEMQoL-Proxy).

Methods: Care home residents aged ≥60 years who were diagnosed with dementia or demonstrated impairment in cognition were recruited from four care facilities in Hong Kong. Caregivers of these participants were also invited to participate. The original DEMQoL-Proxy was translated into Chinese (Cantonese) by a trained translator. The forward-translated version was reviewed by an expert panel of six experienced healthcare professionals. Revisions were made based on comments. The instrument was back-translated to English to check whether further changes were necessary. Demographic data (age, sex, type and severity of dementia, and Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score) were collected from medical records of participants with dementia. Caregivers were interviewed by an occupational therapist or personnel supervised by the occupational therapist using the C-DEMQoL-Proxy and the Chinese version of Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease-Proxy (C-QoL-AD-Proxy). Acceptability, reliability, and validity of the C-DEMQoL-Proxy were evaluated using standard psychometric methods.

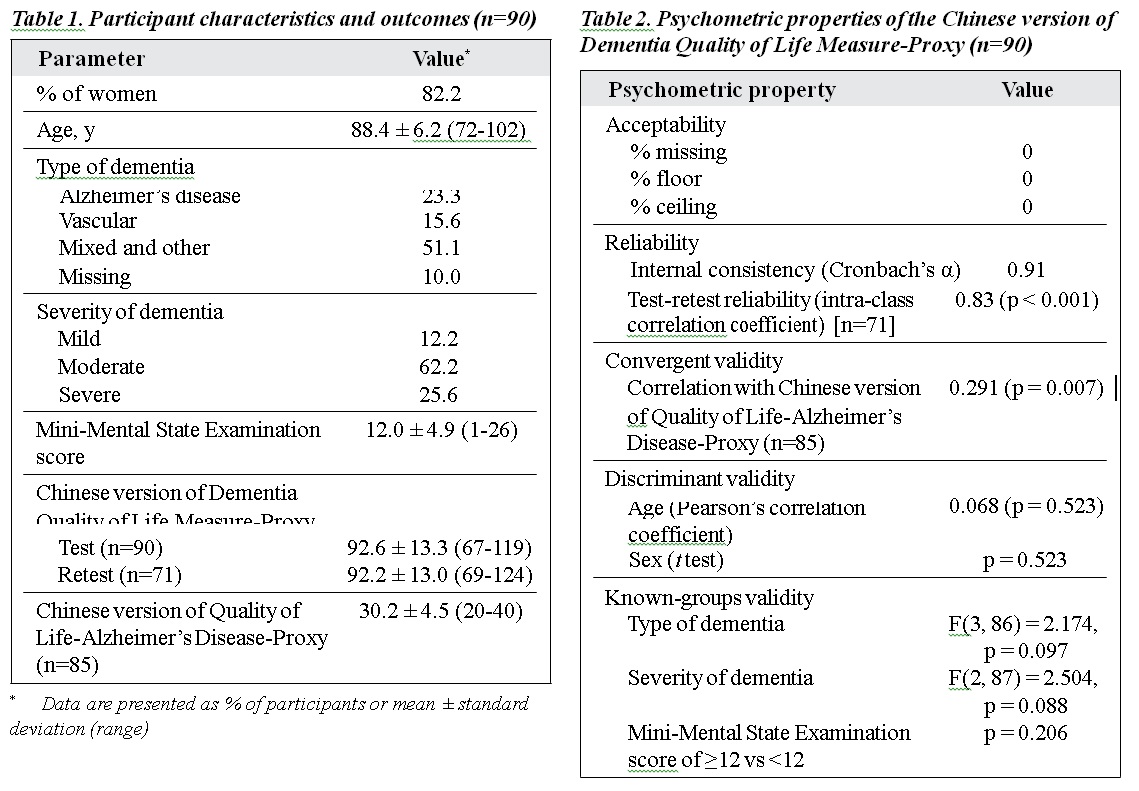

Results: 90 individuals (82.2% women) with dementia aged 72 to 102 years were included. Their diagnosis included Alzheimer’s disease (23.3%), vascular dementia (15.6%), mixed and other types of dementias (51.1%), and missing (10%). Severity was mild in 12.2%, moderate in 62.2%, and severe in 25.6%. The mean MMSE score was 12.0 ± 4.9. 20% of the caregivers were family members and the rest were professional carers. The C-DEMQoL-Proxy had good acceptability, with no floor or ceiling effects or missing data. It had good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.91) and test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.83). It was mildly correlated with C-QoL-AD-Proxy (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). Age and sex were not correlated with C-DEMQoL-Proxy scores. C-DEMQoL-Proxy scores were not significantly different between dementia types, severity levels, or between those with higher or lower MMSE scores.

Conclusion: The C-DEMQoL-Proxy is a valid and reliable instrument to assess health-related quality of life in individuals with dementia.

Key words: Dementia; Quality of life; Validation study

Introduction

Dementia is a chronic neurodegenerative disease that causes cognitive impairments in domains such as attention, memory, and executive function.1,2 Patient welfare and quality of life (QoL) is the priority in designing and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions.3 Health-related QoL (HRQoL) is a construct with multiple dimensions that mirrors the affected person’s perception of the influence of a health condition on daily living.4,5 QoL of patients with dementia: QoL can be assessed by those who endure the condition and as perceived by a proxy or caregiver.6 There are discrepancies between patient and proxy reports.7,8

Dementia Quality of Life Measure (DEMQoL) and DEMQoL-Proxy (DEMQoL-Proxy) specifically assess HRQoL in individuals with dementia,4 with the former completed by those with dementia and the latter by an interviewer for the caregiver. DEMQoL-Proxy is intended as a practical alternative for those with later stages of dementia when self-report becomes more difficult and less reliable. Reliability and validity for both tools in other languages have been reported.4,5,9 Culturally relevant HRQoL measures are Quality of Well-being,12 and EuroQol-5-Dimensions13 have been used to assess the health of individuals with dementia, but they may lack the sensitivity to identify changes in conditions. DEMQoL is a disease-specific instrument for all phases of dementia and can be administered in a wide range of clinical settings.4 This study aims to translate the DEMQoL-Proxy into Chinese (Cantonese) and evaluate its psychometric properties.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Tung Wah College. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. Care home residents aged ≥60 years who were diagnosed with dementia according to the DSM-IV or DSM-V14,15 or demonstrated impairment in cognition according to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were recruited from four care facilities in Hong Kong. Participants had functional disabilities and were unable to live independently in the community and required nursing care. Caregivers of these participants were also invited to participate.

The DEMQoL-Proxy comprises 31 items on feelings, memory, and everyday life. It was translated into Chinese (Cantonese) by a trained translator. The forward-translated version was reviewed by an expert panel of six experienced healthcare professionals in the fields of physical and occupational therapy and social work. Revisions were made based on comments. The instrument was back-translated to English to check whether further changes were necessary.

Demographic data (age, sex, type and severity of dementia, and MMSE score) were collected from medical records of participants with dementia. Caregivers were interviewed by an occupational therapist or personnel supervised by the occupational therapist using the Chinese version of the DEMQoL-Proxy (C-DEMQoL-Proxy) and the Chinese version of Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s Disease- Proxy (C-QoL-AD-Proxy).16

The C-DEMQoL-Proxy comprises 31 questions in three categories: feelings (n=11), memory (n=9), and everyday life (n=11) that assess general health, relationships with others, cognition, psychological well-being, and self- perception. Responses of each question range from 1 (a lot), 2 (quite a bit), 3 (a little) to 4 (not at all); total score ranges from 31 to 124; higher scores indicate better QoL. To evaluate test-retest reliability, 71 of the caregivers completed the retest approximately 2 weeks later.

The C-QoL-AD-Proxy comprises 13 items for physical health, energy, mood, living situation, memory, family, marriage, friends, self as a whole, ability to do chores, ability to do things for fun, overall life quality, and money management.17 Caregivers rate patients’ situation as poor, fair, good, or excellent. Total scores range from 13 to 52; higher scores indicate better QoL. It has good psychometric properties. Administration of C-QoL-AD- Proxy is less time-consuming than C-DEMQoL-Proxy.

Acceptability, reliability, and validity of the C-DEMQoL-Proxy were evaluated using standard psychometric methods.9,18 For acceptability, the cut-off for floor or ceiling effects was set at 15%. If the worst score (31) or the best score (124) comprises >15% of all scores reported, the effects are considered present.19 The cut-off for missing data was <5%. Reliability (internal consistency) was considered good when Cronbach’s alpha was ≥0.70. Test-retest reliability was considered good when the intra-class correlation coefficient was ≥0.70. Convergent validity was determined by Pearson’s correlation between C-DEMQoL-Proxy and C-QoL-AD-Proxy. As these two instruments measure similar constructs (HRQoL), a significant correlation was expected. Discriminant validity was determined by C-DEMQoL-Proxy scores’ correlation with the age and sex of participants. Known- groups validity was determined by comparisons of mean C-DEMQoL-Proxy scores for dementia type (Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, mixed and other, missing), severity (mild, moderate, severe), and MMSE score (<12, ≥12).

Results

A total of 90 individuals (82.2% women) with dementia aged 72 to 102 years were included (Table 1). Their diagnosis included Alzheimer’s disease (23.3%), vascular dementia (15.6%), mixed and other types of dementia (51.1%), and missing (10%). Severity was mild in 12.2%, moderate in 62.2%, and severe in 25.6%. The mean MMSE score was 12.0 ± 4.9. 20% of the caregivers were family members and the rest were professional carers including occupational therapists, social workers, nurses, and health workers/assistants.

For C-DEMQoL-Proxy, acceptability was good, as there were no floor or ceiling effects or missing data. Reliability (internal consistency) was good, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91. Test-retest reliability was also good (0.83). For convergent validity, C-DEMQoL-Proxy was mildly correlated with C-QoL-AD-Proxy (r = 0.29, p = 0.007). For discriminant validity, C-DEMQoL-Proxy was not associated with age or sex of participants. For known-groups validity, C-DEMQoL-Proxy scores did not significantly differ between different types (F(3, 86) = 2.174, p = 0.097) or severity (F(2, 87) = 2.504, p = 0.088) of dementia or MMSE scores of ≥12 or <12 (p = 0.206) [Table 2].

Discussion

The C-DEMQoL-Proxy showed satisfactory to good psychometric properties and can be used for caregivers of

those with later stages of dementia. It had good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, with adequate convergent and discriminant validity. Its correlation with disease-specific C-QoL-AD-Proxy was lower than expected. This may be because our participants were more cognitively impaired (indicated by poorer MMSE scores) than those in the original study (12.0 vs 16.8)4 or the study in Spain (12.0 vs 19.5).9 When severe cases were excluded, the correlation was similar (r = 0.29).4 In addition, the lower correlation may be attributed to differences in living arrangements between studies. In previous studies, individuals with dementia were still living in their own home or family member’s home.4,9 As some items in C-QoL-AD-Proxy (eg, money management, ability to do chores, and ability to do things for fun) might not be fully applicable to those living in a residential setting, correlation with C-DEMQoL-Proxy may thus be affected.

There were no significant differences among types or severity of dementia. This indicated that type and severity of dementia were not major factors that determined HRQoL. Therefore, respectable QoL can still be achieved by those with dementia in all stages of disease progression and severity.9,20 The presence of depressive symptoms may be a better determinant of QoL in those with dementia.9

One limitation to the present study was the small sample size. Nevertheless, the C-DEMQoL-Proxy is appropriate for evaluating HRQoL in those with mild to severe dementia. The psychometric properties of the C- DEMQoL-Proxy were satisfactory to good. Future research should be conducted for the self-report DEMQoL. The self- administered version of C-DEMQoL-Proxy can also be developed to enable more flexible and practical use.5

Conclusion

The C-DEMQoL-Proxy is a valid and reliable instrument to assess HRQoL in individuals with dementia.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Lui VW, Lam LC, Luk DN, Chiu HF, Appelbaum PS. Neuropsychological performance predicts decision-making abilities in Chinese older persons with mild or very mild dementia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2010;20:116-22.

- Liu KP, Kuo MC, Tang KC, Chau AW, Ho IH, Kwok MP, et al. Effects of age, education and gender in the Consortium to Establish a Registry for the Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD)-Neuropsychological Assessment Battery for Cantonese-speaking Chinese elders. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:1575-81. Crossref

- Ettema TP, Dröes RM, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW. A review of quality of life instruments used in dementia. Qual Life Res 2005;14:675-86. Crossref

- Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood RH, Foley B, Smith P, et al. Development of a new measure of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: DEMQOL. Psychol Med 2007;37:737-46. Crossref

- Hendriks AAJ, Smith SC, Chrysanthaki T, Black N. Reliability and validity of a self-administration version of DEMQOL-Proxy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;32:734-41. Crossref

- Grover S, Nehra R, Malhotra R, Kate N. Positive aspects of caregiving experience among caregivers of patients with dementia. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:71-8.

- Huang HL, Chang MY, Tang JS, Chiu YC, Weng LC. Determinants of the discrepancy in patient- and caregiver-rated quality of life for persons with dementia. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:3107-18. Crossref

- León-Salas B, Logsdon RG, Olazarán J, Martínez-Martín P, The Msu-Adru. Psychometric properties of the Spanish QoL-AD with institutionalized dementia patients and their family caregivers in Spain. Aging Ment Health 2011;15:775-83. Crossref

- Lucas-Carrasco R, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Rejas J, Smith SC, Gómez-Benito J. Validation of the Spanish version of the DEMQOL system. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:589-97. Crossref

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf Accessed 28 April 2019.

- Sintonen H. An approach to measuring and valuing health states. Soc Sci Med Med Econ 1981;15:55-65. Crossref

- Kerner DN, Patterson TL, Grant I, Kaplan RM. Validity of the Quality of Well-Being Scale for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Aging Health 1998;10:44-61. Crossref

- Aguirre E, Kang S, Hoare Z, Edwards RT, Orrell M. How does the EQ-5D perform when measuring quality of life in dementia against two other dementia-specific outcome measures? Qual Life Res 2016;25:45-9. Crossref

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. Crossref

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition. American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Papagno C, Cecchetto C, Pisoni A, Bolognini N. Deaf, blind or deaf- blind: is touch enhanced? Exp Brain Res 2016;234:627-36. Crossref

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging 1999;5:21-32. Crossref

- Smith SC, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:1-93. Crossref

- McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 1995;4:293-307. Crossref

- Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, Alvir J, Treglia M, Schwam EM, et al. What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:15-24. Crossref