East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:84-7 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1920

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Samira Masoumian, PhD (Clinical Psychology), School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hooman Yaghmaie Zadeh, MSc (Clinical Psychology), School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Ahmad Ashouri, PhD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Maryam Hejri, MSc (Psychology), School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Mahsa Mirzakhani, MSc (Clinical Psychology), School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Neda Vahed, PhD student of Addiction Studies, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Centre, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Sahel Simiyari, BA (Psychology), School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Address for correspondence: Ahmad Ashouri, PhD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Email: Ashouri.a@iums.ac.ir

Submitted: 17 March 2019 Accepted: 1 November 2019

Abstract

Objectives: To determine the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Food Thought Suppression Inventory (FTSI) in overweight university students in Iran.

Methods: A sample of 233 overweight students were recruited from five universities in Tehran. Participants were asked to complete the Persian versions of FTSI, Binge Eating Scale, Thought Control Questionnaire, Rumination Response Scale, and Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants were also collected.

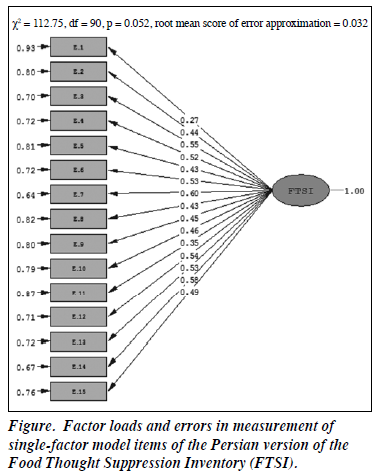

Results: Validity of the Persian version of the FTSI was verified by the fitting indices of the proposed single-factor model of the main makers (χ2 = 112.75, df = 90, p = 0.052, χ2 / df = 1.25, goodness-of- fit index = 0.93, comparative fit index = 0.96, non-normed fitness index = 0.96, root mean score of error approximation = 0.032, and standardised root mean residual = 0.052). Internal consistency of the instrument was high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88.

Conclusion: The Persian version of the FTSI is a valid and reliable tool for screening patients in obesity clinics and for evaluating treatment outcomes.

Key words: Reproducibility of results; Validation study

Background

Thought suppression related to severe psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and obesity has been widely discussed.1,2 However, suppressing thoughts or deliberate attempts to prevent certain thoughts may have unintended consequences such as increased readiness for such thoughts and thus rumination.3 Efforts to prevent unwanted thoughts about eating or weight may lead to an increase in such unwanted thoughts and food search habits and even food intake. Intentional attempts to suppress food thoughts are empirically related to overeating periods in obese or overweight people.4,5 People on a weight-loss diet may be less able to suppress thoughts about food and weight, especially when they are obese, compared with people not on such a diet. Food thought suppression is associated with weight-related outcomes.6 Suppression of food thoughts also predicts eating disorder in young women. However, the suppression of negative emotions in people with a breakthrough does not result in an increase in food.

According to the World Health Organization in 2014, >9.1 billion adults were overweight, and >600 million of them were obese.7 In 2014, about 13% of the adult population (11% men and 15% women) in the world were obese.7 The worldwide prevalence of obesity has doubled from 1980 to 2014.7 Obesity is associated with diabetes, stroke, gout, infertility, certain cancers, and respiratory diseases.8,9 Obesity imposes huge burden on the healthcare system.

The Food Thought Suppression Inventory (FTSI) was developed based on the White Bear Suppression Inventory. Although the FTSI has high reliability,10,11 it has not been validated in Iranian populations. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the reliability and validity of the Persian version of FTSI in overweight university students in Iran. If suppression of food thoughts is associated with the ability to maintain a healthy weight, studies of suppression of food thoughts on weight control can help therapists to demonstrate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural approaches in treating obesity.

Methods

Multistage cluster sampling was used. Five universities from Tehran were selected at random, and then three colleges from each university were selected, and then 20 students from each faculty were selected during the academic year of 2017-18. Inclusion criteria were those aged 20 to 45 years with body mass index (BMI) of >25 (overweight or obese). Trained researchers introduced the study to participants. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire to collect data such as age, sex, education, history of obesity treatment, highest body weight in the last year, and satisfaction with participation. In addition, participants were asked to complete the Persian versions of FTSI, Binge Eating Scale, Thought Control Questionnaire, Rumination Response Scale, and Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. 30% of the sample were re-evaluated 2 weeks later to assess the test-retest reliability.

The FTSI was independently translated from English to Farsi by two translators who were familiar with the field of psychology and test making but have not seen the questionnaire. Each translator provided a translation and a list of possible alternative translations. At a joint meeting of the main researcher and translators, a unitary version was developed. Then two English professors back-translated the FTSI from Farsi to English. At a joint meeting of the main researcher and translators, the Farsi version and the original version were compared and corrections made, and the final version was used.

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed through content validity, convergent validity, and factor analysis. The final version was evaluated by five psychologists and psychiatrists with experience in the field of obesity. The Lawshe method12 was used to determine content validity using two indicators: content validity ratio and content validity index. For the content validity ratio, the five experts were asked to rate the importance and necessity of each item in a three-point Likert scale (1 = not necessary, 2 = useful but not necessary, and 3 = necessary). Higher scores indicate higher levels of content validity. If more than half of the experts consider an item necessary, then the item has a minimum content validity. The content validity index was calculated using the Waltz and Bausell method.13 Each item was evaluated in terms of relevance, clarity, and simplicity based on a 4-part licit spectrum. The minimum acceptable value was 0.79.

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using the Lisrel software. Given that there was no consensus among the structural equation modelling specialists on which of the fitness indicators provided better estimates than the model, a combination of three to four indicators was suggested. Therefore, we used absolute fitness indices, ratio of Chi-squared to degree of freedom (χ2 / df), goodness- of-fit index, and root mean score of error approximation, as well as among the adaptive maturity or comparative fitness indicators, Tucker-Lewis fit index or non-normed fitness index, and comparative fit index. To ensure normal distribution of data for factor analysis, we examined the skewness and elongation of the items. None had more than 2 skewing or 3 elongations. Therefore, all items were normal and entered into the analysis.

Convergent validity was assessed by correlating the FTSI with the Binge Eating Scale, Thought Control Questionnaire, Rumination Response Scale, and Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire.

The FTSI comprises 15 questions about the general tendency to avoid thinking about food in a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Total scores range from 15 to 75; higher scores indicate higher food thought suppression. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.97 to 0.96.6 The FTSI is relevant to the outcome of weight-loss treatment; people who were being treated for weight-loss had higher levels of food thought suppression.14

The Binge Eating Scale15 measures the prevalence of binge eating in obese people. The scale consists of 16 sentence groups that measure the dysfunction of cognitive- emotional dimensions (such as guilty feelings, limited- working and restricted-eating habits, and behaviours such as fast eating and fast food eating). Subjects must choose from 16 groups of 3 or 4 sentences that best describe their feelings about their problems with eating behaviour control. Scores are 1 to 3 for 3-sentence groups and 4 to 1 for 4-sentence groups. Total scores range from 16 to 62; higher scores indicate lower eating behaviour control. Scores of <17 are indicative of a lack of neurological dysfunction. The Persian version of the Binge Eating Scale has been validated using a test-retest method (0.72), a method of doubling (0.67), and a Cronbach’s alpha test (0.85).16 It has a sensitivity of 68.4% and a specificity of 80.8% using the cutoff score of 17.16

The Thought Control Questionnaire17 is a 29-item self-assessment scale to determine the frequency of utilising five thought control strategies: distraction, punishment, re- evaluation, social control, and concern. Each item is rated in a 4-point Likert scale from almost never (1) to almost always (4). Total scores range from 29 to 116; higher scores indicate higher thought control. It has relatively high five subsystems (0.83-0.63) based on a test-retest method.17 It has a valid retest 2 weeks later, and five factors are identified.18

The Rumination Response Scale19 measures 22 items in three subscales (distraction, contemplation, and thoughtfulness) in a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Total scores range from 22 to 88; higher scores indicate more rumination.20 It has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 to 0.92.21

Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire consists of 33 questions in three subscales: restrained, emotional, and external eating behaviour. It has acceptable reliability, internal consistency, and factor validity.22

Data analysis was performed using descriptive statistics, correlation coefficient, and exploratory factor analysis.

Results

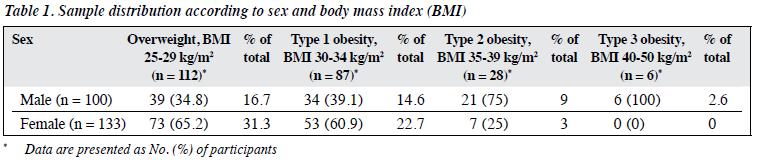

Nearly 8% of returned questionnaires were incomplete. Therefore, a total of 100 male and 133 female university students (mean age, 28 ± 2.8 years) in Tehran were analysed. Of them, 52% were undergraduate students, 30.7% were master’s students, 4.9% were doctoral students, and 12.3% were medical students. 89% were single and 11% were married. 15% reported having at least one physical or psychological illness for >6 months. 57% had undergone treatment for obesity, and 67% experienced weight changes over the past year. 31% were overweight female students (Table 1).

The content validity of the items of the Persian version of FTSI was calculated using the formula’s effect method. All questions had a score of ≥1.7 and thus all were included.

The validity of the Persian version of FTSI was verified by the fitting indices of the single-factor model of the main makers (χ2 = 112.75, df = 90, p = 0.052, χ2 / df = 1.25, goodness-of-fit index = 0.93, comparative fit index = 0.96, non-normed fitness index = 0.96, root mean score of error approximation = 0.032, and standardised root mean residual = 0.052). Factor loading showed that all routes were as significant as the original version (Figure). All path coefficients were >0.20, the highest being 0.60 for item 7 and the lowest being 0.27 for item 1. However, the factors showed a low correlation of 0.48.

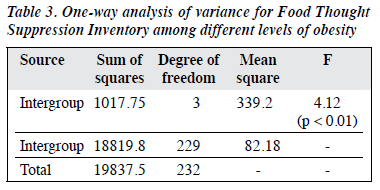

Internal consistency of the Persian version of FTSI was high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. The correlation of FTSI with other scales was 0.79 at the level of p < 0.01. Suppression of food thoughts was positively correlated with overeating, thought control, rumination responses, and eating behaviours (p < 0.01, Table 2). BMI was not associated with suppression of food thought. These findings confirmed the convergent validity of the FTSI. However, the level of food thought suppression varied among different levels of obesity. The highest FTSI score was for type 1 obesity (37.39), and the lowest FTSI score was for type 3 obesity (29.37) [Table 3]. There was no significant difference between female and male students in the FTSI score (34.96 vs 34.75, df = 231, t = 0.16, p = 0.86).

Discussion

The Persian version of FTSI is an acceptable instrument with sufficient validity and reliability among overweight university students in Tehran. The internal consistency of the Persian version of FTSI was 0.88, which is lower than the 0.97 to 0.96 for the original version of FTSI.6 The Persian version of FTSI had a good test-retest reliability of 0.79 at the level of p < 0.01. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of FTSI were consistent with the those reported in other studies.10,11

Nonetheless, the present study has limitations. The sample was made up of university students in Tehran; generalisation of results to other cities and other population groups may be limited. Future study should include samples with a variety of demographic characteristics in other cities and universities as well as in various clinical groups and people.

Conclusion

Given the high validity and reliability, the Persian version of FTSI can be used for screening patients in obesity clinics and for evaluating treatment outcomes.

Declaration

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding / support

The research was financially supported by Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional and/or national research committee.

References

- Klein AA. Suppression-induced hyperaccessibility of thoughts in abstinent alcoholics: a preliminary investigation. Behav Res Ther 2007;45:169-77. Crossref

- Barnes RD, Sawaoka T, White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Factor structure and clinical correlates of the Food Thought Suppression Inventory within treatment seeking obese women with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 2013;14:35-9. Crossref

- Wenzlaff RM, Wegner DM. Thought suppression. Annu Rev Psychol 2000;51:59-91. Crossref

- Harnden JL, McNally RJ, Jimerson DC. Effects of suppressing thoughts about body weight: a comparison of dieters and nondieters. Int J Eat Disord 1997;22:285-90. Crossref

- Johnston L, Bulik CM, Anstiss V. Suppressing thoughts about chocolate. Int J Eat Disord 1999;26:21-7. Crossref

- Barnes RD, Tantleff-Dunn S. Food for thought: examining the relationship between food thought suppression and weight-related outcomes. Eat Behav 2010;11:175-9. Crossref

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2015. Intergroup 1017.75 3 339.2 4.12

- Clarkson GP, Hodgkinson GP. What can occupational stress diaries achieve that questionnaires can’t? Personnel Rev 2007;36:684-700. Crossref

- Thong JY, Yap CS. Information systems and occupational stress: a theoretical framework. Omega 2000;28:681-92. Crossref

- Barnes RD, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Food thought suppression: a matched comparison of obese individuals with and without binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 2011;12:272-6. Crossref

- Barnes RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. Examining the relationship between food thought suppression and binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:1077-81. Crossref

- Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol 1975;28:563-75. Crossref

- Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: design statistics and computer analysis. Philadelphia: FA Davis Co; 1981.

- Barnes RD, Ivezaj V, Grilo CM. Food Thought Suppression Inventory: test-retest reliability and relationship to weight loss treatment outcomes. Eat Behav 2016;22:93-5. Crossref

- Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 1982;7:47-55. Crossref

- Mootabi F, Moloodi R, Dezhkam M, Omidvar N. Standardization of the Binge Eating Scale among Iranian obese population. Iranian J Psychiatry 2009;4:143-6.

- Wells A, Davies MI. The Thought Control Questionnaire: a measure of individual differences in the control of unwanted thoughts. Behav Res Ther 1994;32:871-8. Crossref

- Fata L, Moutabi F, Moloudi R, Ziayee K. Psychometric properties of Persian version of thought control questionnaire and anxious thought inventory in Iranian students. J Psychol Models Methods 2000;1:81-103.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991;61:115-21. Crossref

- Muris P, Roelofs J, Rassin E, Franken I, Mayer B. Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety and depression. Pers Individ Dif 2005;39:1105-11. Crossref

- Luminet O. Measurement of depressive rumination and associated constructs. In: Depressive Rumination: Nature, Theory and Treatment. Chichester: Wiley; 2004: 185-215. Crossref

- Van Strien T, Frijters JE, Bergers GP, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord 1986;5:295-315. Crossref