East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2020;30:48-51 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1875

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Tiraya Lerthattasilp, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Thailand

Pairath Tapanadechopone, MD, PhD, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Thailand

Panida Butrdeewong, BNS, Thammasat University Hospital, Pathumthani, Thailand

Address for correspondence: Dr Tiraya Lerthattasilp, Department of Psychiatry, Thammasat University Hospital, Klong Luang, Rangsit, Pathumthani, 12121 Thailand.

Email: clinictu@gmail.com

Submitted: 29 March 2019 Accepted: 1 April 2019

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the validity and reliability of a Thai version of the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ).

Methods: The present study included 23 children with depressive disorders (diagnosis made by child psychiatrists) and 74 children with no depressive disorders. All children and their parents were asked to complete the Thai versions of the SMFQ, Children’s Depression Inventory, and Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. Criterion validity, convergent validity, reliability, and parent-child agreement of the SMFQ were measured.

Results: With a cut-off score of 9, the child-rated SMFQ yielded a sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 86.5%, whereas the parent-rated SMFQ yielded a sensitivity of 82.6% and a specificity of 89.2%. The correlation coefficient between the child-rated and parent-rated versions was 0.75, and the correlation coefficients between the Thai Children’s Depression Inventory and the child-rated and parent-rated versions were 0.86 and 0.74, respectively. Respectively for the child-rated and parent-rated versions, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 and 0.923, and the intra-class correlation coefficient was 0.61 and 0.75. The Bland-Altman plot showed that 92.9% and 85.7% of the child and parent test-retest answers were within limits of agreement.

Conclusion: The Thai version of SMFQ has a high degree of psychometric validity and reliability.

Key words: Adolescent; Child; Depressive disorder

Introduction

Depressive disorders occur in 1% to 2% of pre-pubertal children and 7.5% of adolescents; they are at increased risk for impairment in education and interpersonal relationships and for suicidal behaviours.1-3

The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) is a screening tool for depression in children and adolescents aged 6 to 17 years. It consists of 33 descriptive phrases regarding how the child has been feeling or acting recently. Children are asked whether descriptions in the questionnaire for them are ‘true’, ‘sometimes true’, or ‘not true’ during the past two weeks. Scores range from 0 to 66, and higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.4-8 The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) selects 13 items that perform well in a variety of analyses of pooled items to cover depressive phenomenology in DSM and ICD.9 Both MFQ and SMFQ have good psychometric properties in both clinical and community samples.10-13 The MFQ has been translated into Thai and has shown high validity and reliability, with the area under the curve (AUC) of 0.94 in the child version, 0.93 in the parent version, and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 in both versions.14 Nonetheless the MFQ requires a considerable amount of time to complete. The SMFQ has only 13 items and is more time-efficient for initial screening of clinical disorders and for measuring clinical changes in a large sample. The aim of the present study was to develop a Thai version of the SMFQ and to assess its psychometric properties.

Methods

This study was registered in the ethics committee of Thammasat University (reference: MTU-EC-PS-6_104/58). Demographic characteristics (sex, age, level of education, and diagnosis) of 97 patients aged 7 to 18 years who visited Thammasat University Hospital during January to December 2017 were shared with a study of psychometric properties of the Thai MFQ.14 The depressed sample consisted of 23 patients diagnosed with depressive disorders (major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder with depressive episode) by child psychiatrists based on DSM-5 criteria. The diagnosis was made within the past month to reflect the 2-week reference period of the SMFQ. The non-depressed sample consisted of 74 patients who presented with a variety of general health problems (eg, allergic rhinitis, dermatitis, and muscle strain) and had no mood disorders diagnosed. Those with intellectual disability or severe physical disabilities or those who could not read Thai were excluded. A sample size of 23 depressed patients and 69 non-depressed patients was estimated to give 80% power at a 5% significance level (two- sided) with a sensitivity of 0.76 and a specificity of 0.78.11

The Thai SMFQ had been translated by a team of child and adolescent psychiatrists and a licensed translator. Another translator then back-translated it into English. The two translations were compared by both parties. The Thai SMFQ had been tested in a pilot sample of 10 pairs of Thai children and parents.

The Thai SMFQ comprises 13 items on affective and cognitive symptoms. Children and their parents were asked to rate each item statement as true (2 points), sometimes true (1 point), or not true (0 point) within a period of 2 weeks. The maximum total score is 26; higher scores indicate higher depressive symptomatology. The average time to complete each SMFQ was about 5 minutes.

The children were also asked to complete the Thai version of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), which has acceptable psychometric properties. The CDI comprises 27 items; each item consists of three statements regarding symptoms with different levels of severity. Children selected the one best described how they felt and thought during the preceding 2 weeks. Each item is rated as 0, 1, or 2. The maximum total score is 54; higher scores indicate higher depressive symptomatology. At the cut-off of 15, sensitivity was 0.79 and specificity was 0.91.15-18 The Thai CDI was used to assess the convergent validity of the Thai SMFQ.

The children and their parents were also asked to complete the MFQ on their own or with the examiner reading it for them. 14 pair of children and parents were asked to complete the SMFQ again after 2 weeks to assess the test-retest reliability.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14. Those with or without depressive disorders were compared in terms of demographic characteristics and SMFQ scores using Fisher’s exact test or independent t test. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the accuracy of the parent- rated and child-rated versions of the SMFQ. The sensitivity and specificity of both parent and child versions of the SMFQ against the clinical diagnosis of depressive disorders were calculated at different cut-offs. The correlation between the total SMFQ score and the total MFQ score, between the total SMFQ score and the total CDI score, and the parent-child agreement were examined using Pearson correlation coefficient. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine the internal reliability of the SMFQ. The test- retest reliability was examined using a Bland-Altman plot and intra-class correlation coefficient.

Results

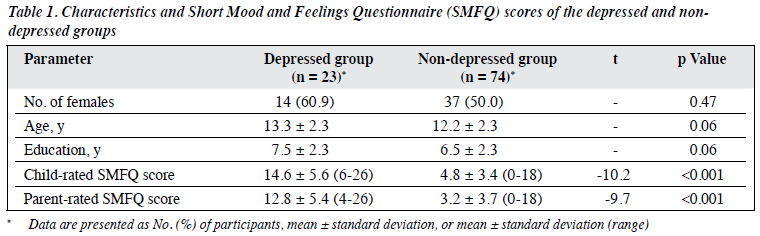

23 children with depressive disorders (major depressive disorders [n = 12], persistent depressive disorders [n = 9], and bipolar disorder in depressive episode [n = 2]) and 74 children without depressive disorders were included. The two groups were comparable in terms of demographic characteristics (Table 1).

Compared with patients without depressive disorders, patients with depressive disorders had higher child-rated SMFQ score (14.6 vs 4.8, p < 0.001) and parent-rated SMFQ score (12.8 vs 3.2, p < 0.001) [Table 1].

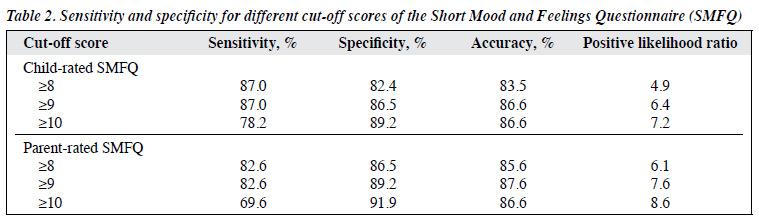

With the clinical diagnosis as the gold standard, the child-rated SMFQ was accurate in detecting depressive disorders, with an AUC of 0.94. At the cut-off score of 9, the positive likelihood ratio was 6.4, with equal sensitivity and specificity of 0.87. The parent-rated SMFQ also had an AUC of 0.94. At the cut-off score of 9, the positive likelihood ratio was 7.6, with sensitivity of 0.83 and specificity of 0.89 (Table 2).

Regarding convergent validity, the correlation coefficients between the Thai SMFQ (child and parent versions) and the Thai CDI were 0.86 and 0.74, respectively. The correlation coefficients between child-rated SMFQ and child-rated MFQ, and between parent-rated SMFQ and parent-rated MFQ were equally at 0.97.

Regarding parent-child agreement, the correlation coefficient between child-rated SMFQ and parent-rated SMFQ was 0.75.

Internal consistency for both child- and parent-rated versions of Thai SMFQ was high, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90 and 0.93, respectively.

Regarding test-retest reliability, the child-rated SMFQ had an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.613 (95% confidence interval = 0.144-0.857). A Bland-Atman plot revealed that 92.86% of test-retest answers were within limits of agreement, with a mean difference of 3.571, and 95% limits of agreement of -4.662 to 11.805 (Figure a). The parent-rated SMFQ had an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.753 (95% confidence interval = 0.390-0.913). A Bland- Atman plot revealed that 85.71% of test-retest answers were within limits of agreement, with a mean difference of 2.50, and 95% limits of agreement of -5.139 to 10.139 (Figure b).

Discussion

Both the child-rated and parent-rated Thai SMFQ had good known-group validity, diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. The accuracy of Thai SMFQ is similar to that of Thai MFQ reported in a study (child-rated MFQ: sensitivity = 0.87, specificity = 0.93; parent-rated MFQ: sensitivity = 0.87, specificity = 0.85).14 The child-rated version of Thai SMFQ had higher sensitivity and specificity than that of other SMFQs reported by Angold et al9 (sensitivity = 0.60, specificity = 0.85), Thapar and McGuffin10 (sensitivity = 0.75, specificity = 0.74), and Rhew et al.11 The parent-rated version of Thai SMFQ is similar to that of SMFQ by Thapar and McGuffin10 (sensitivity = 0.86, specificity = 0.87), but is higher than that of the SMFQ by Rhew et al11 (sensitivity and specificity = 0.61-0.66). The differences may result from differences in study samples (community vs hospital), inclusion criteria (new-case vs partial-remission major depressive disorder), and the reference standard diagnosis (clinician diagnosis vs instrumental diagnosis). This study indicated that a total SMFQ score of ≥9 is suggestive of a depressive disorder. However, in practice, clinicians may choose different cut-off scores based on the needed sensitivity and specificity.

The CDI correlated better with the child-rated SMFQ than with the parent-rated SMFQ (correlation coefficient: 0.86 vs 0.74), probably because the CDI is also a child- rated questionnaire. The correlation of the Thai SMFQ with the Thai MFQ was also high (0.97 in both the child and parent versions), consistent with the findings by Angold et al9 (0.96 in child version and 0.91 in parent version). The overall parent and child agreement of the Thai SMFQ was high (r = 0.75). Internal consistency of the child and parent versions was very good (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.90 and 0.92, respectively). The test-retest reliability of the Thai SMFQ was also good but lower than that of the Thai MFQ.14

The present study has limitations. The sample is small and the results may not be generalised to the community population. Further studies on community populations are warranted.

Conclusion

The Thai version of the SMFQ shows a high degree of psychometric validity and reliability. It is a promising tool for screening depressive disorders in children and adolescents of Thailand.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a research project grant awarded by Thammasat University.

Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ. The epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. In: Goodyer IM, editor. Cambridge Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The depressed child and adolescent. Cambridge University Press; 2001: 143-78. Crossref

- Harrington R. Depression, suicide and deliberate self-harm in adolescence. Br Med Bull 2001;57:47-60. Crossref

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, Rutter M. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression. Suicidality, criminality and social dysfunction in adulthood. Br J Psychiatry 2001;179:218-23. Crossref

- Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988;27:726-37. Crossref

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Depression in Children and Young People: Identification and Management in Primary, Community and Secondary Care. Leicester: British Psychological Society; 2005.

- Kent L, Vostanis P, Feehan C. Detection of major and minor depression in children and adolescents: evaluation of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997;38:565-73. Crossref

- Daviss WB, Birmaher B, Melhem NA, Axelson DA, Michaels SM, Brent DA. Criterion validity of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire for depressive episodes in clinic and non-clinic subjects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:927-34. Crossref

- Wood A, Kroll L, Moore A, Harrington R. Properties of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1995;36:327-34. Crossref

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. The development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1995;5:237-49.

- Thapar A, McGuffin P. Validity of the shortened Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in a community sample of children and adolescents: a preliminary research note. Psychiatry Res 1998;81:259-68. Crossref

- Rhew IC, Simpson K, Tracy M, Lymp J, McCauley E, Tsuang D, et al. Criterion validity of the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire and one- and two-item depression screens in young adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2010;4:8. Crossref

- Sharp C, Goodyer IM, Croudace TJ. The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ): a unidimensional item response theory and categorical data factor analysis of self-report ratings from a community sample of 7-through 11-year-old children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2006;34:379-91. Crossref

- Turner N, Joinson C, Peters TJ, Wiles N, Lewis G. Validity of the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire in late adolescence. Psychol Assess 2014;26:752-62. Crossref

- Lerthattasilp T, Tapanadechopone P, Butrdeewong P. Validity of the Thai version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). J Psychiatr Assoc Thailand 2018;63:179-88.

- Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull 1985;21:995-8.

- Trangkasombat U, Likanapichitkul D. The Children’s Depression Inventory as a screen for depression in Thai children. J Med Assoc Thai 1997;80:491-9.

- Trangkasombat U, Likanapichitkul D. Prevalence and risk factors for depression in children: an outpatient pediatric sample. J Med Assoc Thai 1997;80:303-10.

- Trangkasombat U. Likanapichitkul D. Depressive symptom in children: a study using the Children’s Depression Inventory. J Psychiatr Assoc Thailand 1996;41:221-30.