East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:20-5 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1749

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Minh Son Nguyen, DDS, Institute of Dentistry, University of Tartu, Estonia; Danang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy, Vietnam

Paula Reemann, MD, PhD, Radiology Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Dagmar Loorits, MD, Radiology Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Pilvi Ilves, MD, PhD, Radiology Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia

Triin Jagomägi, DDS, PhD, Institute of Dentistry, University of Tartu, Estonia Toai Nguyen, DDS, PhD, Faculty of Stomatology, Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam

Mare Saag, DDS, PhD, Institute of Dentistry, University of Tartu, Estonia

Ülle Voog-Oras, MD, PhD, Institute of Dentistry, University of Tartu, Estonia

Address for correspondence: Dr Minh Son Nguyen, Institute of Dentistry, University of Tartu, Estonia. Email: minhson1883@gmail.com

Submitted: 29 August 2017; Accepted: 21 June 2018

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed (1) to determine the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and TMJ osseous changes in elderly Vietnamese according to sex and residence, and (2) to investigate the association of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) osseous changes with anxiety, depression, and limitation of mandibular function.

Methods: Elderly people living in Danang, Vietnam were recruited. Participants were screened for anxiety and depression using the self-reported 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), respectively. Participants then self-rated the limitation of their mandibular function using the 20-item Jaw Functional Limitation Scale (JFLS-20) questionnaire. TMJ osseous changes (erosion, flattening, osteophytes, and sclerosis) were evaluated using digital orthopantomography.

Results: Of 179 participants aged 65 to 74 years, 17.9% and 35.8% had anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively. Compared with urban residents, rural residents had higher prevalence of anxiety (23.3% vs 12.4%, p = 0.009) and depression (46.62% vs 24.7%, p = 0.019). The prevalence of TMJ osseous changes was 58.1%. The most common TMJ osseous change was flattening (41.3%), followed by erosion (34.6%), sclerosis (16.2%), and osteophytes (7.8%). Participants with or without TMJ osseous changes were comparable in terms of GAD-7 score, PHQ-9 score, and JFLS-20 score and sub-scores. Conclusions: Anxiety and depression and TMJ osseous changes were prevalent in elderly Vietnamese. Rural residents had higher prevalence of anxiety and depression than urban residents. TMJ osseous changes were not associated with anxiety, depression, or limitation of mandibular function.

Key words: Aged; Anxiety; Bone diseases; Depression; Mandibular condyle

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) osseous changes are a low- inflammatory arthritic degenerative disease. The prevalence of TMJ osseous changes varies among population-based studies, ranging from 11.6% to 68.1%.1-3 The rate of TMJ osseous changes is associated with the progression of degeneration: the early signs were erosion or flattening, whereas osteophytes and sclerosis were the last stage of degeneration.4 Radiographic studies of TMJ osseous changes among the general population have reported a prevalence of 6% to 70% for erosion, 21% to 80% for flattening, 3% to 50% for osteophytes, and 8.5% to 24% for sclerosis.1-3,5,6 TMJ osseous changes occur gradually after middle age and thus are known as an age-related disease.

The effect of ageing on mental health has been reported. The prevalence of psychological disorders among adult populations has been reported to be 16% to 40% in Europe, 11% to 39% in Asia, and 7% to 29% in the US.7-14 In Vietnam, >40% of older adults have psychological disorders, which are associated with demographic characteristics.15 Psychological disorders affect daily activities and quality of life and increase the risk of diseases and chronic pain in elderly people.15-18

TMJ osseous changes can progress to TMJ disorders (TMJD), which is a common cause of orofacial pain.19 It has been reported that 45% to 53% of patients with TMJD pain often have anxiety and depression.20

The two TMJs act simultaneously to perform rotational and translational movements of the mandible. TMJ osteoarthritis increases the risk of limited mouth opening by 1.5 to 7.5 times.21 TMJ osseous changes can cause disharmony among the masticatory structures and limitation of mandibular function.

The Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders axis II has been used to evaluate the psychological aspects and mandibular function (such as mastication, motion, verbal and emotional expression) in patients with TMJD.22,23 This study aimed (1) to determine the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and TMJ osseous changes in elderly Vietnamese according to sex and residence, and (2) to investigate the association of TMJ osseous changes with anxiety, depression, and limitation of mandibular function.

Methods

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Danang University of Medical Technology and Pharmacy (No. 523/CN-DHKTYDDN) and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. This cross-sectional study examined the oral health status and clinical and psychological aspects of TMJD in elderly people living in Danang, Vietnam. Participants were randomly selected based on sex and residence.

Assuming a 50% prevalence of any TMJD among the population, 5% of acceptable error margin, and 10% of compensation for withdrawn participants, 300 participants were recruited to achieve a 90% confidence level. Of them, 55 were absent on the day of clinical and radiographic examinations and 66 had unreadable TMJ structures on orthopantomographs. The final sample included 179 participants.

Participants were screened for anxiety and depression using the self-reported 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)24 and 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),25 respectively. The GAD-7 measures the frequency of each anxious mood item from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). Total score ranges from 0 to 21; scores of 5, 10, and 15 indicate mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively. The PHQ-9 measures the frequency of each depressed mood item from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). Total score ranges from 0 to 27; scores of 5-9, 10-14, 15-19, and ≥20 indicate mild, moderate, moderate- severe, and severe depression, respectively. Participants with GAD-7 score of ≥10 and PHD-9 score of ≥10 were defined as having anxiety and depression, respectively.

Participants then self-rated the limitation of their mandibular function using the 20-item Jaw Functional Limitation Scale (JFLS-20) questionnaire.26 The JFLS-20 evaluates limitation of mandibular function related to mastication (6 items), mandibular mobility (4 items), verbal and emotional expression communication (8 items), swallowing (1 item), and yawning (1 item), with score of each item ranging from 0 (least limited) to 10 (most limited) and total score ranging from 0 to 200.

All questionnaires were translated from English to Vietnamese and then back-translated to check the veracity of the translation by two professional translators. Internal consistency of questionnaire items was assessed using the Cronbach’s alpha analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.698 for GAD-7, 0.783 for PHQ-9, and 0.869 for JFLS-20, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

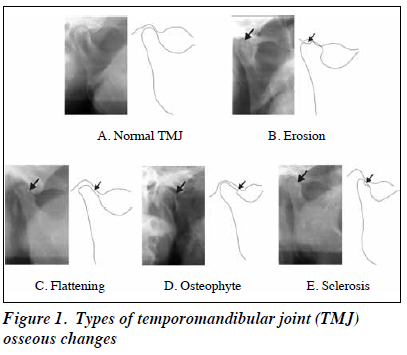

TMJ osseous changes were evaluated using digital orthopantomography set at 73 kV, 10 mA, and 17.6 s with a CC-detector sensor (Soredex Cranex D, Tuusula, Finland). TMJ osseous changes were classified to (1) erosion: a decreased density of the cortical and subcortical layers of the condylar bone, (2) flattening: a loss of smooth and divergence from the convex shape of the condyle, (3) osteophyte: local outgrowth of bone arising from a mineralize joint surface, and (4) sclerosis: an increased density of the cortical bone extending into bone marrow (Figure 1).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 17; SPSS Inc, Chicago [IL] llinois, USA). The prevalence of anxiety, depression, and TMJ osseous changes between men and women and between rural and urban residence was compared using the Chi-squared test. Comparisons between TMJ osseous changes and GAD-7, PHQ-9, and JFLS-20 scores were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Spearman’s test was used to determine correlations among TMJ osseous changes (yes/no), GAD-7, PHQ9, and JFLS-20 scores. All p values were two-sided, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 179 (90 female and 89 male) participants aged 65 to 74 years (mean, 69.7 ± 3.9 years) were analysed. 50.3% were rural residents; 58.7% had duration of education ≥5 years. The mean number of missing teeth was 7.6 ± 6.9; 34.1% had lost >8 teeth.

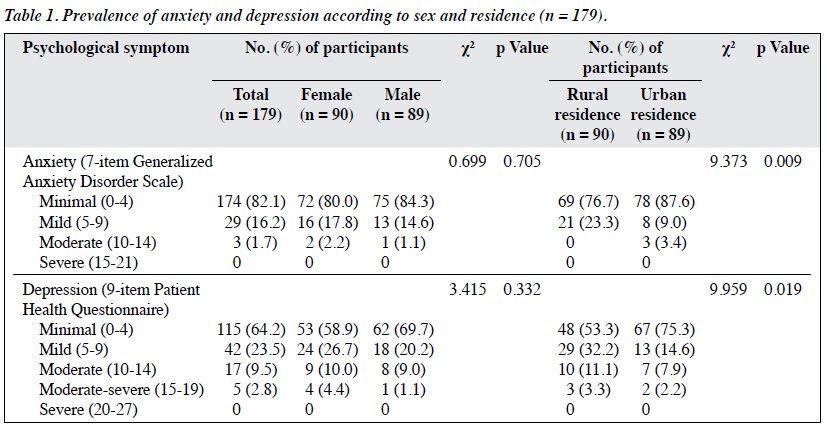

Of the participants, 16.2% had mild and 1.7% had moderate anxiety, whereas 23.5% had mild, 9.5% had moderate, and 2.8% had moderate-severe depression. None had severe anxiety or depression. Male and female participants were comparable in terms of the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms. Compared with urban residents, rural residents had higher prevalence of anxiety (23.3% vs 12.4%, p = 0.009) and depression (46.62% vs 24.7%, p = 0.019) [Table 1].

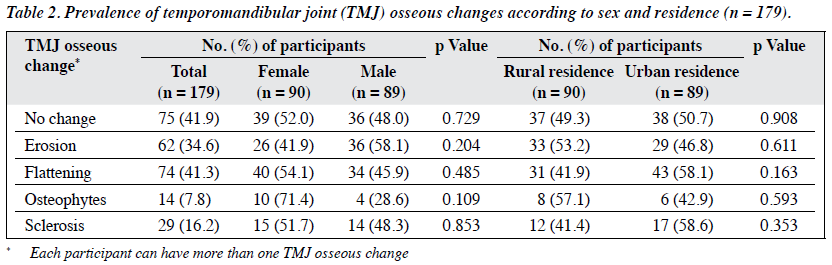

The prevalence of TMJ osseous changes was 58.1%. The most common TMJ osseous change was flattening (41.3%), followed by erosion (34.6%), sclerosis (16.2%), and osteophytes (7.8%). The patient distribution in terms of TMJ osseous changes did not differ significantly between males and females and between rural and urban residences (Table 2).

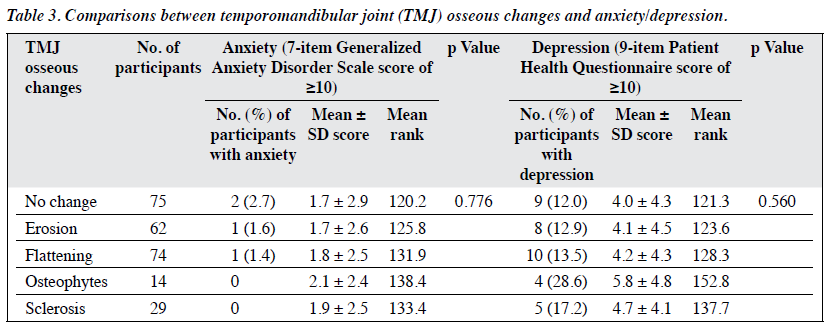

Participants with or without TMJ osseous changes were comparable in terms of GAD-7 score (1.7 to 2.1 vs 1.7, p = 0.776) and PHQ-9 score (4.1 to 5.8 vs 4.0, p = 0.560), as well as the prevalence of anxiety (1.4% to 1.6% vs 2.7%) and depression (12.9% to 28.6% vs 12%) [Table 3].

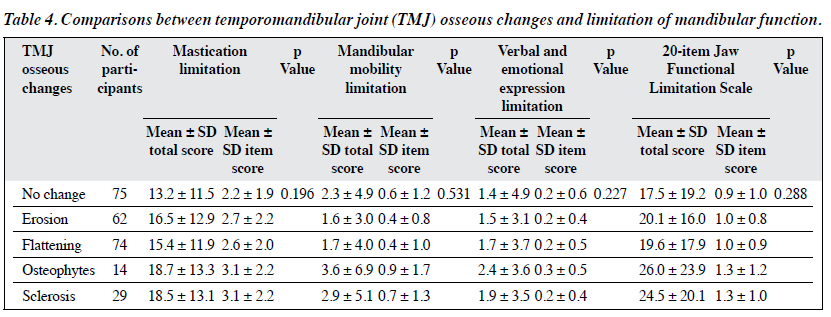

Participants with or without TMJ osseous changes were comparable in terms of JFLS-20 score (19.6 to 26.0 vs 17.5, p = 0.288) as well as sub-scores of mastication limitation (15.4 to 18.7 vs 13.2, p = 0.196), mandibular mobility limitation (1.6 to 3.6 vs 2.3, p = 0.531), and verbal and emotional expression limitation (1.5 to 2.4 vs 1.4, p = 0.227) [Table 4].

Positive correlations were found between anxiety and depression (r = 0.665, p < 0.001), between limitation of mandibular function and anxiety (r = 0.304, p < 0.001), and between limitation of mandibular function and depression (r = 0.320, p < 0.001). However, TMJ osseous changes were not correlated with anxiety, depression, or limitation of mandibular function (Figure 2).

Discussion

Anxiety

In our study, the prevalence of depression (PHQ-9 score of ≥10) was 12.3%, which was lower than that reported in India,8 China,11,14 and Vietnam,15 but was in line with that reported in Japan10 and Germany.12 Depression was more prevalent in rural residents than in urban residents, probably because rural residents encounter greater material hardship, whereas urban residents emphasise more on health and quality of life. Depression and anxiety were positively correlated, in accordance with other studies that reported comorbidity of depression and anxiety.14,15 Nonetheless, the prevalence of anxiety (GAD-7 score of ≥10) was low in our participants. This may be because Vietnamese elderly people usually live with their descendants as traditional extended families; they join social activities in local community that provide emotional supports from their children, relatives, and friends.

The prevalence of TMJ osseous changes varies across the general population: 58.1% in our participants, 57% in an Estonia population,3 31.6% in Finnish elderly people,1 11.6% in Japanese people aged >25 years,2 and 81% in Indian people.6

TMJ osseous changes are signs of age-related degeneration. Mechanical factors such as para-function, function overloading, and increased joint friction result in cartilage breakdown of the TMJ and lead to a degenerating joint.27 In addition, chondrocyte senescence secondary to a low level of mineral bone density may increase the risk of cartilage degeneration; conversely, these changes may negatively affect remodelling of articular cartilage.3

As edentulism is common among elderly populations and results in a loss of occlusal support, TMJ osseous changes become more prevalent.1,2

Among types of TMJ osseous changes,1-3,28 flattening and erosion are commonly observed among general populations.1,2,29-31 Flattening results from function overloading of the TMJ owing to decline in occlusal support. Erosion is the first stage of the degenerative joint disease. In the advanced stage, TMJ subchondral bone is remodelled and both osteophytes and sclerosis occur in the anterior part of TMJ condyle.1,3,27,31

Psychiatric morbidity, particularly anxiety and depressive disorders, was prevalent in patients with osteoarthritis.32 Similarly, psychological stressors may influence TMJ osseous changes. For instance, anxiety and stress are related to bruxism, which may cause micro-break in cartilage surfaces of TMJ.4,33 Conversely, TMJD pain is also a stress-related disorder. In Israel, 22.7% and 24.6% of patients with TMJD were reported to have depression and anxiety, respectively.34 In Croatia, 19.5% of patients were reported to have comorbidity of psychological disorders and TMJD,35 whereas in Italy it was 31.9%.20 In our study, anxiety and depression were not associated with TMJ osseous changes. The prevalence of anxiety and depression was similar in participants with or without TMJ osseous changes. This is likely because our sample was selected from the healthy general population with low prevalence of anxiety and depression. In addition, the degenerative joint disease is a low-inflammation condition that may not cause high-intensity pain that leads to anxiety or depression.

In our study, the JFLS-20 score for mandibular functions was similar between participants with or without TMJ osseous changes. This indicated that TMJ osseous changes were not correlated with mandibular dysfunction. A JFLS-20 score of 2.2 was suggested to be a threshold for mastication limitation for patients with TMJD,36 but the norms for JFLS-20 sub-scales have not been established yet. Our participants with TMJ osseous changes had a mean mastication limitation score of 2.6 to 3.1, probably because of impaired masticatory performance secondary to loss of teeth. In addition, TMJ osseous changes were not correlated with anxiety, depression, or limitation of mandibular function. Nonetheless, anxiety and depression scores positively increased with score of limitation of mandibular function. Our previous study reported that 49.6% and 25.2% of elderly people frequently had headaches and orofacial pain, respectively,37 which may cause anxiety, depression, and impaired mandibular function.38

Our study has several limitations. The sample was selected in the central area of Danang and thus not representative of the entire country. Although orthopantomography is widely used to assess TMJ osseous changes, minor osseous changes are difficult to detect. Cone beam computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should have been used for more accurate assessment. Limitation of mandibular function was evaluated using the self-reported JFLS-20; more clinical assessment should have been made.

Conclusion

Anxiety and depression and TMJ osseous changes are prevalent in elderly Vietnamese. Rural residents have higher prevalence of anxiety and depression than do urban residents. TMJ osseous changes were not associated with anxiety, depression, or limitation of mandibular function.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an Estonian Science Foundation grant (No 9255), an Estonian Research Council IUT 20–46 grant, and the European Social Fund’s Doctoral Studies and Internationalisation Programme Dora, which is administered by Foundation Archimedes.

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Hiltunen K, Vehkalahti MM, Peltola JS, Ainamo A. A 5-year follow-up of occlusal status and radiographic findings in mandibular condyles of the elderly. Int J Prosthodont 2002;15:539-43.

- Takayama Y, Miura E, Yuasa M, Kobayashi K, Hosoi T. Comparison of occlusal condition and prevalence of bone change in the condyle of patients with and without temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;105:104-12. Crossref

- Jagur O, Kull M, Leibur E, Kallikorm R, Loorits D, Lember M, et al. Relationship between radiographic changes in the temporomandibular joint and bone mineral density: a population based study. Stomatologija 2011;13:42-8.

- Tanaka E, Detamore MS, Mercuri LG. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dent Res 2008;87:296-307. Crossref

- Al-Ekrish AA, Ekram M. A comparative study of the accuracy and reliability of multidetector computed tomography and cone beam computed tomography in the assessment of dental implant site dimensions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2011;40:67-75. Crossref

- Mathew AL, Sholapurkar AA, Pai KM. Condylar changes and its association with age, TMD, and dentition status: a cross-sectional study. Int J Dent 2011;2011:413639. Crossref

- Copeland JR, Beekman AT, Braam AW, Dewey ME, Delespaul P, Fuhrer R, et al. Depression among older people in Europe: the EURODEP studies. World Psychiatry 2004;3:45-9.

- Barua A, Kar N. Screening for depression in elderly Indian population. Indian J Psychiatry 2010;52:150-3. Crossref

- Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:1025-39. Crossref

- Hidaka S, Ikejima C, Kodama C, Nose M, Yamashita F, Sasaki M, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among older Japanese people: comorbidity of mild cognitive impairment and depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:271-9. Crossref

- Yu J, Li J, Cuijpers P, Wu S, Wu Z. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: a population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:305-12. Crossref

- Wild B, Herzog W, Schellberg D, Lechner S, Niehoff D, Brenner H, et al. Association between the prevalence of depression and age in a large representative German sample of people aged 53 to 80 years. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;27:375-81.

- Barcelos-Ferreira R, Nakano EY, Steffens DC, Bottino CM. Quality of life and physical activity associated to lower prevalence of depression in community-dwelling elderly subjects from Sao Paulo. J Affect Disord 2013;150:616-22. Crossref

- Chan WC, Wong CS, Chen EY, Ng RM, Hung SF, Cheung EF, et al. Validation of the Chinese Version of the Revised Clinical Interview Schedule: findings from Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:3-10.

- Leggett A, Zarit SH, Nguyen NH, Hoang CN, Nguyen HT. The influence of social factors and health on depressive symptoms and worry: a study of older Vietnamese adults. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:780-6. Crossref

- Chan SW, Shoumei JI, Thompson DR, Yan HU, Chiu HF, Chien WT, et al. A cross-sectional study on the health related quality of life of depressed Chinese older people in Shanghai. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:883-9. Crossref

- Komiyama O, Obara R, Iida T, Nishimura H, Okubo M, Uchida T, et al. Age-related associations between psychological characteristics and pain intensity among Japanese patients with temporomandibular disorder. J Oral Sci 2014;56:221-5. Crossref

- Tung KY, Cheng KS, Lee WK, Kwong PK, Chan KW, Law AC, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in Chinese adults with type 1 diabetes in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:128-36.

- Conti PC, Pinto-Fiamengui LM, Cunha CO, Conti AC. Orofacial pain and temporomandibular disorders: the impact on oral health and quality of life. Braz Oral Res 2012;26 Suppl 1:120-3. Crossref

- Manfredini D, Ahlberg J, Winocur E, Guarda-Nardini L, Lobbezoo F. Correlation of RDC/TMD axis I diagnoses and axis II pain-related disability. A multicenter study. Clin Oral Investig 2011;15:749-56. Crossref

- Wiese M, Svensson P, Bakke M, List T, Hintze H, Petersson A, et al. Association between temporomandibular joint symptoms, signs, and clinical diagnosis using the RDC/TMD and radiographic findings in temporomandibular joint tomograms. J Orofac Pain 2008;22:239-51.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/ TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014;28:6-27. Crossref

- Ohrbach R, Knibbe W. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: scoring manual for self-report instruments. Available at: www.rdc-tmdinternational.org. Accessed 1 April 2018.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7. Crossref

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13. Crossref

- Ohrbach R, Larsson P, List T. The jaw functional limitation scale: development, reliability, and validity of 8-item and 20-item versions. J Orofac Pain 2008;22:219-30.

- Talaat W, Al Bayatti S, Al Kawas S. CBCT analysis of bony changes associated with temporomandibular disorders. Cranio 2016;34:88-94. Crossref

- Wiese M, Wenzel A, Hintze H, Petersson A, Knutsson K, Bakke M, et al. Osseous changes and condyle position in TMJ tomograms: impact of RDC/TMD clinical diagnoses on agreement between expected and actual findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;106:e52-63. Crossref

- Crow HC, Parks E, Campbell JH, Stucki DS, Daggy J. The utility of panoramic radiography in temporomandibular joint assessment. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2005;34:91-5. Crossref

- dos Anjos Pontual ML, Freire JS, Barbosa JM, Frazão MA, dos Anjos Pontual A. Evaluation of bone changes in the temporomandibular joint using cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2012;41:24-9. Crossref

- Shetty US, Burde KN, Naikmasur VG, Sattur AP. Assessment of condylar changes in patients with temporomandibular joint pain using digital volumetric tomography. Radiol Res Pract 2014;2014:106059. Crossref

- Wong LY, Yiu RL, Chiu CK, Lee WK, Lee YL, Kwong PK, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in Chinese subjects with knee osteoarthritis in a Hong Kong orthopaedic clinic. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:150-8.

- Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg K, Manfredini D, Hublin C, Sinisalo J, et al. Self-reported bruxism mirrors anxiety and stress in adults. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2013;18:e7-11. Crossref

- Reiter S, Emodi-Perlman A, Goldsmith C, Friedman-Rubin P, Winocur E. Comorbidity between depression and anxiety in patients with temporomandibular disorders according to the research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2015;29:135-43. Crossref

- Celić R, Braut V, Petricević N. Influence of depression and somatization on acute and chronic orofacial pain in patients with single or multiple TMD diagnoses. Coll Antropol 2011;35:709-13.

- Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F, Gonzalez Y, Gordon S, Gremillion H, et al. Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain 2011;12(11 Suppl):T27-45. Crossref

- Nguyen MS, Jagomägi T, Nguyen T, Saag M, Voog-Oras U. Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders among elderly Vietnamese. Proc Singapore Healthc 2017;26:211-6. Crossref

- List T, John MT, Ohrbach R, Schiffman EL, Truelove EL, Anderson GC. Influence of temple headache frequency on physical functioning and emotional functioning in subjects with temporomandibular disorder pain. J Orofac Pain 2012;26:83-90.