East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2017;27:71-8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prof. Sandeep Grover, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Prof. Ritu Nehra, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr Rama Malhotra, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Dr Natasha Kate, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Sandeep Grover, Department of Psychiatry, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160012, India.

Tel: (91-172) 2756 807; Fax: (91-172) 2744 401 / 2745 078; Email: drsandeepg2002@yahoo.com

Submitted: 5 April 2016; Accepted: 8 November 2016

Abstract

Objective: To assess the positive aspects of caregiving and its correlates among caregivers of patients with dementia.

Methods: A total of 55 primary caregivers of patients with dementia were invited to complete the Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience (SPACE), Coping Checklist, Social Support Questionnaire, and World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF version. Caregivers were also assessed by a clinician using the Burden Interview Schedule. Patients were assessed using the Hindi Mental State Examination and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale.

Results: The mean SPACE domain score was highest for motivation for caregiving role (2.63) followed by caregiver satisfaction (2.54), caregiving personal gains (2.4), and self-esteem and social aspect of caring (2.23). More educated caregivers scored significantly lower in the self-esteem and social aspect of caring. Married caregivers had a higher mean score in the motivation for caregiving role. There were some correlations between subjective burden and various SPACE domains, but the total objective burden score had no correlation with the SPACE. Higher use of avoidance coping was associated with a positive caregiving experience. Stronger social support was associated with higher score in the motivation for caregiving role. Higher level of caregiver burden in various domains was associated with lower motivation for caregiving. Caregiver satisfaction was associated with better quality of life for caregivers in terms of the environment.

Conclusion: A positive caregiving experience for primary caregivers of patients with dementia is associated with both objective and subjective burdens, avoidance coping, and perceived social support.

Key words: Caregivers/psychology; Dementia

Introduction

Due to high dependency needs, the role of caregivers in the management of dementia is vital. Such caregivers spend a lot of their time in caregiving and may consequently neglect their own health and experience psychological morbidity and poor physical health.1-4 Caregiving is also associated with a sense of satisfaction and pride that derives from the care-related activity and provides a sense of purpose in the caring role.5

Various theoretical frameworks have been proposed to understand the caregiving outcome. Of these, the predominant framework is that of a stress appraisal model, according to which the outcome of the caregiving stress on the caregiver is influenced by the stressor (i.e. caregiving demands), mediators (in the form of coping, social support, personality of the caregiver), and the positive and negative appraisal of their caregiving role.3

In general, there is more literature on the negative impact of caregiving and only a few studies have evaluated the positive aspects of caregiving.6,7 Positive aspects of the caregiving experience (PACE) is considered a subjective event. Research suggests that such positive aspects are not opposite to negative aspects, can be experienced along with the negative caregiving outcomes, and bear a modest correlation with the negative aspects of caregiving.8,9

There is marked heterogeneity in understanding the PACE. Most literature on the PACE is in the form of qualitative studies. These qualitative studies suggest that various authors have understood PACE in terms of emotional rewards as well as job satisfaction related to feeling appreciated as a caregiver, personal growth, self- respect, being more self-aware, increased faith and spiritual growth, a sense of mastery or competency in the role of caregiving, improved relationships (carers described gains relating to companionship and simply being in the company of their husband or wife), greater emotional closeness, increased intimacy in the relationship, and reciprocity or the opportunity to give back to their loved one leading to satisfaction, a sense of duty and expressed pride in being able to care for their lifelong partners.7 In terms of the process of caregiving, various positive aspects of caregiving noted across different studies include acceptance of or coming to terms with the situation, practising a positive caregiving attitude, satisfaction of caregiving, ‘hope’ or ‘meaning’, counting blessings, or choosing to use humour to make a positive situation out of a negative one, commitment to a relationship, creating opportunities for the care recipient to engage in meaningful activities, and drawing strength from various sources in order to remain positive.7

Very few studies have evaluated the correlates of PACE. Some suggest that a positive caregiving experience is more likely when the caregiver is a man of an older age-group and the caregiver has a low family income.8

Frequency of care (hours spent per day) correlates with satisfaction in many studies suggesting that caregivers derive greater satisfaction when they spend more time in caregiving activities.9 Other studies show no relationship between duration of caregiving and satisfaction.10,11 Many psychological variables such as coping strategies, religious practices, and perceived social support have been shown to have some influence on the positive caregiving experience of caregivers of patients with cancer and serious mental disorders.11 Nonetheless very few studies have evaluated the same among the caregivers of patients with dementia. One such study suggested that spirituality correlates positively with PACE and it may partially mediate the effect of subjective stress on PACE.12

As most of the literature derives from qualitative studies, few instruments have been designed to evaluate PACE. Those available include the positive caregiving experience domain of Experience of Caregiving Inventory, Caregiving Satisfaction Scale, Caregiver Appraisal Scale, Caregiving Gains Scale, Finding Meaning Through Caregiving Scale, and Positive Aspects of Caregiving Scale. Recently, the Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience (SPACE) was validated in India.13

In India, most of the mental health care is provided at an outpatient level and financed by the patient / family. In general there are very few rehabilitation facilities. A major part of the health care is provided by the private health care system and is generally more expensive than that provided in the government sector.

The major burden of care of patients with mental illnesses is borne by the family. They are not only responsible for bringing the patient to the treatment facility, but must also make decisions about treatment, supervise medication, pay for treatment, stay with the patient in the hospital in case he / she is admitted, care for the patient at home, liaise with mental health professionals, and take care of the rehabilitation needs of the patient. Apart from these, they also try to assume the role assigned to the sufferer and compensate for their inability to fulfil said role. In the majority of cases, caregivers assume this role voluntarily.

This results in neglect of their own health and delay in their own life issues. Despite these demands, they remain largely uncomplaining, as they consider it a duty of care to their ill relative.14 This situation arises because of the traditional family structure in which there is a great deal of emotional interdependence among various family members with strong interpersonal empathy, closeness, and dependence on each other.14 Nonetheless lack of treatment and rehabilitation facilities in general increases the burden on caregivers who bear the full brunt of caring for their ill relative. Few studies from India have evaluated the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with dementia. Those available have not evaluated the positive aspects of caregiving among caregivers. Accordingly the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the experience of positive aspects of caregiving among caregivers of patients with dementia. The secondary aim of this study was to evaluate the association of positive aspects of caregiving with caregiver burden, coping, and social support. It was hypothesised that there would be no relationship or negative relationship between positive aspects of caregiving and caregiver burden.

Methods

This study was carried out in the psychiatry outpatient setting of a multispeciality tertiary care hospital in northern India. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the institute and patients were recruited after obtaining written informed consent from the caregivers and, if possible, the patients.

The study included patients with a diagnosis of dementia of any subtype as per the DSM-IV criteria, age > 50 years, and those accompanied by a primary caregiver to the psychiatry outpatient services. Primary caregivers were defined as those involved in the care of the patient, living with the patient, supervising the patient’s day-to-day activities, supervising their medication, who stayed with the patient during the hospital stay and were involved in liaison with the treating agency. Caregivers aged ≥ 18 years and involved in the care of the patient for at least 6 months and themselves not diagnosed with a chronic physical or psychiatric disorder (other than tobacco dependence) and able to read Hindi and / or English were included.

The study included 55 patients and their caregivers selected by convenience sampling from those attending the psychiatry outpatient department.

Instruments

Scale for Positive Aspects of Caregiving Experience

The SPACE13 was used to assess the positive aspects of caregiving. This scale comprises 44 items, each rated on a 5-point scale (range, 0-4) with a highest attainable score of 176. This scale was divided into 4 domains, including caregiving personal gains (14 items), motivation for caregiving role (13 items), caregiver satisfaction (8 items), and self-esteem and social aspect of caring (9 items). It is a self-rated scale available in Hindi and English that can be completed by caregivers. A higher score indicates a more positive caregiving experience. Scores obtained for each item are added together to obtain the domain score. The domain score was divided by the total number of items included in the domain to derive the final score for the domain. The scale has good internal consistency, split- half reliability (Spearman-Brown coefficient / Guttman’s split-half coefficient, 0.83), face validity (90% agreement on various items among experts), test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.9-0.99 for various domains), and cross-language reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.92-0.98 for various domains).13

Family Burden Interview Schedule

The Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBI) consists of 24 items that evaluate objective caregiver burden and 1 item to evaluate the subjective caregiver burden. Items for assessing objective burden were grouped into 6 domains, including financial burden, disruption of routine family activities, disruption of family leisure, disruption of family interaction, effect on physical health of others, and effect on mental health of others. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale (range, 0-2) with a score of 0 to 48 for objective burden and 0 to 2 for subjective burden. A higher score indicates heavier burden. This scale has been used widely to assess caregiver burden in many mental disorders and has good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.87) and validity (correlation coefficient, -0.72).15

Coping Checklist

The Coping Checklist–Hindi version comprises 14 items, each rated on a 3-point scale (range, 1-3). A higher score indicates more frequent use of the particular coping mechanism.16 The various items were divided into 5 subscales: problem focused (3 items), seeking social support (4 items), avoidance (5 items), coercion (1 item), and collusion (1 item). The scale has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, -0.62).

World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF Version

The World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF version (WHOQOL-BREF) Hindi version comprises 26 items that evaluate the respondent’s subjective evaluation of health and living conditions. The items were organised into 5 domains, including general health, physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environment with a maximum attainable score of 130. This WHOQOL- BREF version has psychometric properties comparable with the full version of WHOQOL-100. The WHOQOL-BREF also has good discriminant validity, concurrent validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability.17

Hindi Mental Status Examination

The Hindi Mental Status Examination (HMSE) is based on the Mini-Mental State Examination and assesses orientation, attention, registration, recall, and language.18

The items of the scale take account of the literacy level and cultural issues with a maximum total score of 31. The items are modified such that an absent formal education does not hinder administration of this instrument.

Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale

The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL) assesses 8 independent living skills among older adults evaluated in the community, clinic, or hospital setting. When rating, the person was evaluated for their highest level of functioning in that category. The total score for the scale varies from 0 to 8 with lower score indicating a lower level of functioning and higher level of dependency.19

Social Support Questionnaire

The Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ) comprises 18 items, each rated on a 4-point (1-4) scale with a maximum total score of 72. Higher score indicates higher perceived social support. Based on the total score, the available social support was categorised as low (< 40), moderate (40-60), or high (> 60).20

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS (Windows version 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago [IL], US). Continuous variables were analysed as mean ± standard deviation. Frequency and percentages were calculated for nominal and ordinal variables. Associations between positive aspects of caregiving and other variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Spearman correlation coefficient. Comparisons were made using t test and Mann- Whitney U test.

Results

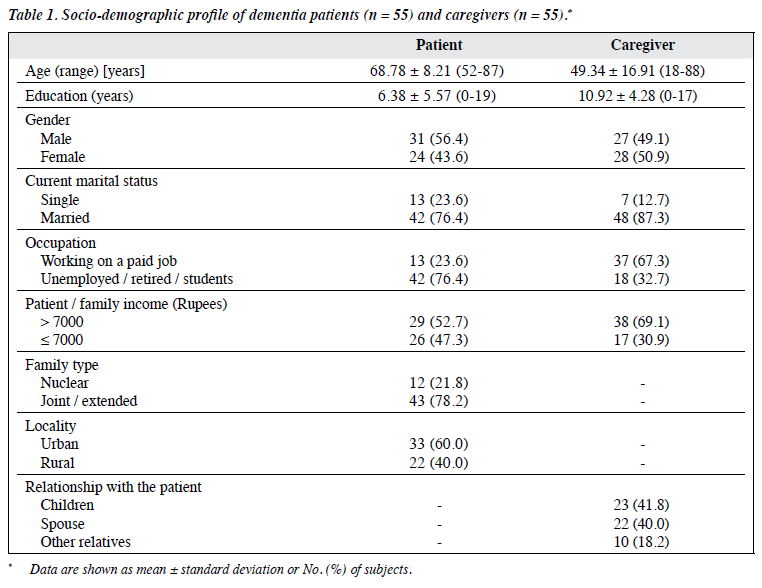

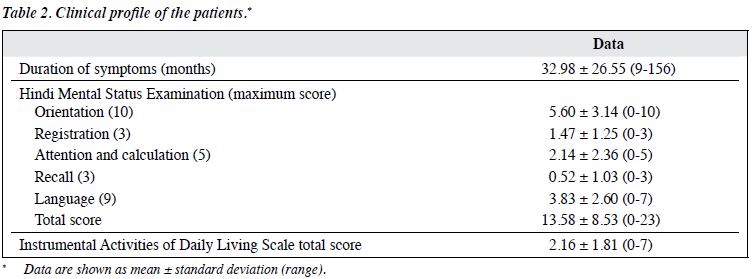

The study included 55 patients and their caregivers. The socio-demographic profile of the patients and caregivers is shown in Table 1. Among the caregivers, 23 were children of the patients and 22 were the spouse. Clinical profiles are shown in Table 2.

Caregiving Profile

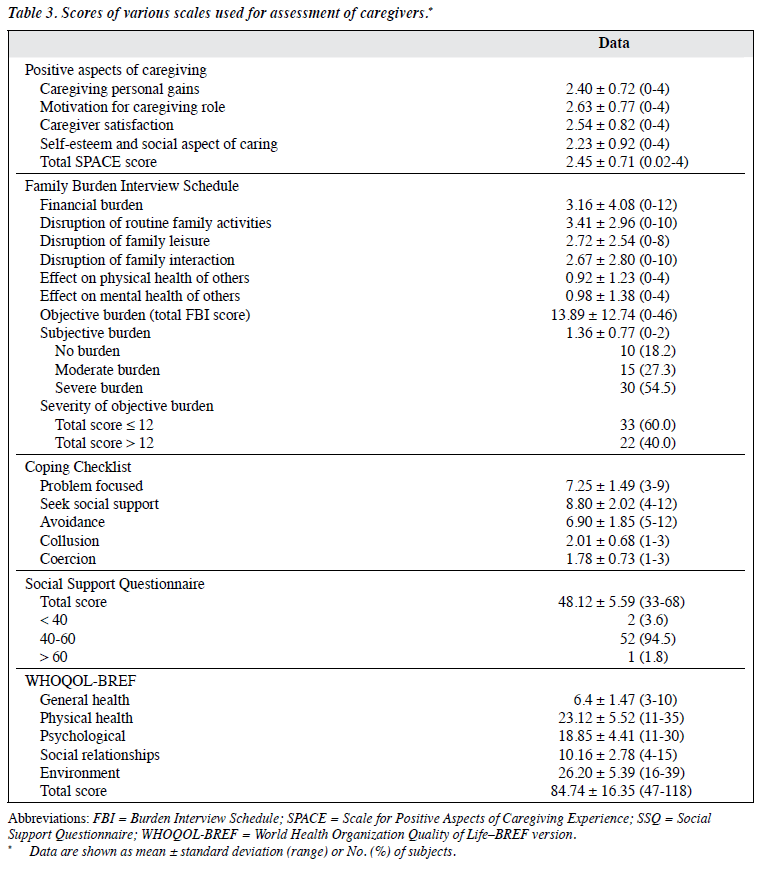

The mean total SPACE score was 2.45. The total FBI score was 13.89, with the highest burden in the domain of disruption of routine family activities followed by financial burden. Details of burden in the other domains are depicted in Table 3. In terms of severity of burden, 40% of caregivers had a mean score of > 12 indicating a severe objective burden. The mean subjective burden score was 1.36. In terms of severity, most caregivers reported a severe subjective burden. In terms of coping, the mean score was highest for the domain of seeking social support followed by problem focused coping and avoidance. The mean SSQ score was 48.12 and most caregivers scored 40 to 60. On WHOQOL- BREF, the mean total score was 84.74 with the highest score for the domain of environment followed by physical health.

Correlates of Positive Aspects of Caregiving

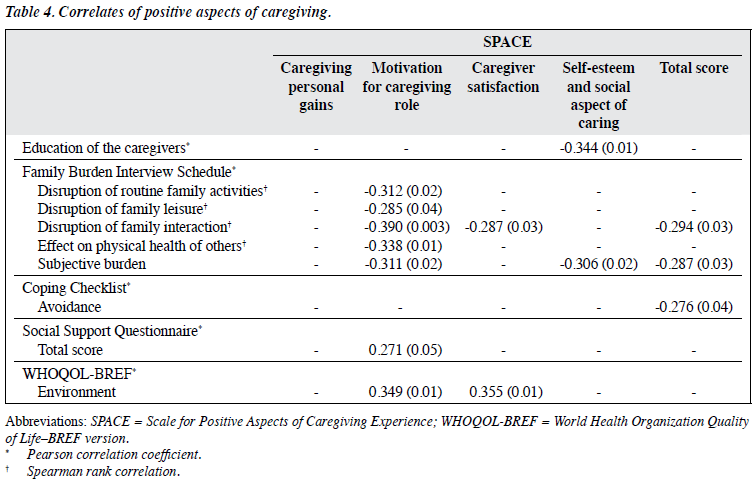

Socio-demographic variables of patients and caregivers had no correlation with the mean SPACE domain or total scores, except for a negative correlation between years of education of caregivers and the domain of self-esteem and social aspect of caring (Table 4). Regarding the mean score in the domain of motivation for caregiving role, married caregivers scored higher than the unmarried (2.73 ± 0.69 vs. 1.94 ± 0.93; t = 2.65; p = 0.01). The mean SPACE domain and total scores also did not correlate with HMSE scores or mean IADL score.

There were few correlations between caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving. The domain of motivation for caregiving role had the maximum number of correlations with FBI and all these were negative correlations, suggesting that a higher level of caregiver burden in various domains is associated with lower motivation for caregiving. There was a significantly negative correlation between the FBI domain of disruption of family interaction and SPACE domain of caregiver satisfaction and overall positive caregiving experience. Subjective caregiver burden also correlated negatively with the SPACE domain of self-esteem and social aspect of caregiving and total SPACE score.

There was no significant difference in the SPACE domain score between those who experienced a high (> 12) and low (≤ 12) objective burden, and between categories of relationship (spouses, children, and others) with the patient.

In terms of coping, only higher use of avoidance was associated with a significantly lower overall positive aspect of caregiving. The SSQ score correlated positively with the domain of motivation for caregiving role. With regard to quality of life (QOL), only WHOQOL-BREF environment domain correlated positively with the domains of motivation for caregiving role and caregiver satisfaction.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study from India to evaluate PACE among caregivers of patients of dementia. In India, most patients with dementia are managed on an outpatient basis and live with their family. Family members are the primary caregivers who try to meet the patient’s treatment needs, personal needs, and rehabilitation needs. The present study focused on this group of caregivers. The findings of the study therefore reflect the experience of an average family caregiver in India.

Our findings suggest that caregivers of patients with dementia do report PACE in multiple domains. In the present study, the SPACE domain of motivation for caregiving role scored the highest while self-esteem and social aspect of caring being the lowest. Accordingly it can be said that caregiving as a process is not always associated with only negative consequences. Many caregivers do experience PACE. Our findings provide credence to some of the existing literature on PACE which suggests that caregiving is associated with various PACE in the form of caregiver satisfaction, personal growth, self-respect, a sense of mastery or competency in the role of caregiving, and satisfaction of caregiving.7

There are 2 published studies that have assessed PACE by using SPACE among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia21 and type 1 diabetes mellitus.22 Comparison of our findings with these studies revealed that the mean scores for various domains are comparable. This suggests that the caregivers of patients with dementia have similar level of PACE to caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders or chronic physical disorders. When comparing the rank order of mean scores of various domains, it was evident that caregivers of patients with dementia in the present study were comparable to the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.21 In contrast, among the caregivers of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, the rank order (self- esteem and social aspect of caring, caregiving personal gains, caregiver satisfaction, motivation for caregiving role) was different.22 Although these differences could be influenced by the patient (age, age at onset, gender) and caregiver (age, relationship with the patient, time spent in

caregiving) characteristics, these suggest that caregiving for patients with mental and physical illnesses is associated with subtle differences in PACE.

Correlates of Positive Aspects of Caregiving

In the present study, none of the socio-demographic variables of the patient correlated with the PACE among caregivers. Previous studies also generally suggest a lack of association of PACE with demographic variables of patients. The present study suggests that caregivers with a lower level of education and who are married report a higher positive caregiving experience in the domains of self-esteem and social aspect of caring and motivation for caregiving role, respectively. The literature on the correlates of PACE is meagre, evolving, and inconsistent. In general, existing literature on the caregivers of patients with severe mental illnesses and elderly patients suggests no significant relationship between the caregiving appraisals and age, gender, and employment of the caregiver.7,23 Previous studies among caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders, cancer, and dementia have produced inconsistent findings with some suggesting that more highly educated caregivers have a more positive caregiving experience.24-26 Other studies suggest a more positive caregiving experience when the patient is female,23,27 when the caregiver is a male, and in those with a low family income,8,28 and when the caregiver is older.29 The findings of the present study support the notion that most of the demographic characteristics of the caregivers do not influence the PACE.

In the present study PACE did not have any correlation with HMSE or IADL score, suggesting that the severity of dementia did not influence PACE significantly. The existing literature on caregivers of patients also suggests that there is only a modest level of correlation between burden and PACE.7 Our study also demonstrated few correlations between caregiver burden and positive aspects of caregiving. This supports the existing literature. Overall, the positive aspect of caregiving correlated with subjective burden and disruption of family interaction. Accordingly it can be said that the objective burden does significantly influence the motivation to be a caregiver whereas the subjective burden influences other domains too. Clinicians should attempt to reduce the subjective burden to improve the overall positive caregiving experience. Additionally, effort must be made to reduce the objective burden in order to maintain caregiver motivation.

The present study suggests that higher use of avoidance coping was associated with significantly lower overall PACE. This finding is understandable since avoidance coping can be at times maladaptive.30 Previous studies among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia did not find a similar association between social support and PACE as seen in the present study.21 Nonetheless, in contrast to the study among the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia, there were few correlations between QOL and SPACE in the present study.21 These differences could be due to different caregiving needs of the patients, caregiver profile, or due to the nature of the illness. The findings of the present study must be considered preliminary and must be evaluated further.

It may not be the severity of illness that determines the experience of the caregiver. It may be that sociocultural variables influence the involvement of caregivers and their caregiving experience. While caring for their ill relative, caregivers experience a significant burden, both subjective and objective. Nonetheless it is the subjective aspects that have a significant association with various domains of PACE. The objective burden is mostly associated with a positive aspect in the form of motivation to be a caregiver. A higher objective burden reduces the motivation to continue as a caregiver and is possibly associated with use of avoidance coping. The present study suggests that caregivers may continue to remain involved in the care of an ill relative because of both positive and negative aspects of caregiving. Hence, the clinician should always evaluate the positive aspects of caregiving in the caregivers of patients with dementia. In the same process, they should make the caregiver realise the rewards that can be derived from their role. This may help caregivers to continue in the caregiver role and reduce the use of avoidance coping.

Limitations

The present study was limited by its small sample size and inclusion of patients of dementia with heterogeneous aetiologies. Further, the study was limited to the caregivers of patients who attended the psychiatry outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital. As such, the findings cannot be generalised to caregivers of patients in the community. The PACE assessed in the present study was limited to the dimensions of the scale used (SPACE) and does not suggest that we were able to tap all the aspects of PACE. The scale used for assessment of coping strategies has unequal items for various types of coping and this could have influenced the association of coping and PACE. Future studies should attempt to overcome these limitations.

Conclusion

To conclude, the present study suggests that PACE is not strongly influenced by the socio-demographic profile of the patients or caregivers. Further, the PACE is not influenced by the severity of dementia or level of dependency. A higher burden in various domains is associated with lower PACE, mainly in the domain of motivation for caregiving role and, to a certain extent, the caregiver satisfaction and self- esteem and social aspects of caregiving. Overall, subjective burden, not overall objective burden, was closely associated with PACE. Interventional strategies for caregivers must focus on reduction of caregiver burden, especially the subjective burden, to ensure their continued motivation as a caregiver, and improve caregiver satisfaction and self- esteem. The present study also suggests that higher use of avoidant coping mechanism is associated with lower PACE. Clinicians should discourage use of avoidant coping

and encourage more adaptive coping mechanisms to deal with caregiving stress. The present study also suggests that stronger social support is associated with higher PACE in the motivation for caregiving role. Clinicians should encourage caregivers to seek more social support from their family and friends. Clinicians should also provide social support for the caregivers to improve their PACE. Our study findings suggest that PACE is associated with better QOL in the environment. Accordingly it can be said that improving the PACE can lead to better QOL for caregivers. This can further enhance the care they provide.

Declaration

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cunningham EL, McGuinness B, Herron B, Passmore AP. Dementia. Ulster Med J 2015;84:79-87.

- Anenshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: the unexpected career. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995.

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990;30:583-94.

- Bell CM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ. The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2001;15:129-36.

- Ribeiro O, Paúl C. Older male carers and the positive aspects of care. Ageing Soc 2008;28:165-83.

- Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: a review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20:423-8.

- Lloyd J, Patterson T, Muers J. The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: a critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia (London) 2016;15:1534-61.

- López J, López-Arrieta J, Crespo M. Factors associated with the positive impact of caring for elderly and dependent relatives. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2005;41:81-94.

- Quinn C, Clare L, Woods B. The impact of the quality of relationship on the experiences and wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health 2009;13:143-54.

- de Labra C, Millán-Calenti JC, Buján A, Núñez-Naveira L, Jensen AM, Peersen MC, et al. Predictors of caregiving satisfaction in informal caregivers of people with dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;60:380-8.

- Kulhara P, Kate N, Grover S, Nehra R. Positive aspects of caregiving in schizophrenia: a review. World J Psychiatry 2012;2:43-8.

- Hodge DR, Sun F. Positive feelings of caregiving among Latino Alzheimer’s family caregivers: understanding the role of spirituality. Aging Ment Health 2012;16:689-98.

- Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Scale for positive aspects of caregiving experience: development, reliability, and factor structure. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2012;22:62-9.

- Avasthi A. Preserve and strengthen family to promote mental health. Indian J Psychiatry 2010;52:113-26.

- Pai S, Kapur RL. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. Br J Psychiatry 1981;138:332- 5.

- Nehra R, Chakrabarti S, Sharma R, Kaur R. Psychometric properties of the Hindi version of the coping checklist of Scazufca and Kuipers. Indian J Clin Psychol 2002;29:79-84.

- Saxena S, Chandiramani K, Bhargava R. WHOQOL-Hindi: a questionnaire for assessing quality of life in health care settings in India. World Health Organization Quality of Life. Natl Med J India 1998;11:160-5.

- Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, et al. A hindi version of the MMSE: the development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry 1995;10:367-77.

- Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, Kleman MH. Multi-level assessment instrument manual for full length MAI. North Wales, PA: Polisher Research Institute; 2004.

- Nehra R, Kulhara P, Verma SK. Adaptation of social support questionnaire in Hindi: Indian setting. Indian J Clin Psychol 1996;23:33-9.

- Kate N, Grover S, Kulhara P, Nehra R. Positive aspects of caregiving and its correlates in caregivers of schizophrenia: a study from north India. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013;23:45-55.

- Grover S, Bhadada S, Kate N, Sarkar S, Bhansali A, Avasthi A, et al. Coping and caregiving experience of parents of children and adolescents with type-1 diabetes: an exploratory study. Perspect Clin Res 2016;7:32-9.

- Pickett SA, Cook JA, Cohler BJ, Solomon ML. Positive parent / adult child relationships: impact of severe mental illness and caregiving burden. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1997;67:220-30.

- Lau DY, Pang AH. Caregiving experience for Chinese caregivers of persons suffering from severe mental disorders. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:75-80.

- Roff LL, Burgio LD, Gitlin L, Nichols L, Chaplin W, Hardin JM. Positive aspects of Alzheimer’s caregiving: the role of race. J Gerontol. B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2004;59:185-90.

- Aggarwal M, Avasthi A, Kumar S, Grover S. Experience of caregiving in schizophrenia: a study from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2011;57:224- 36.

- Mo FY, Chung WS, Wong SW, Chun DY, Wong KS, Chan SS. Experience of caregiving in caregivers of patients with first-episode psychosis. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2008;18:101-6.

- Kang J, Shin DW, Choi JE, Sanjo M, Yoon SJ, Kim HK, et al. Factors associated with positive consequences of serving as a family caregiver for a terminal cancer patient. Psychooncology 2013;22:564-71.

- Hsiao CY, Tsai YF. Caregiver burden and satisfaction in families of individuals with schizophrenia. Nurs Res 2014;63:260-9.

- Deasy C, Coughlan B, Pironom J, Jourdan D, Mannix-McNamara P. Psychological distress and coping amongst higher education students: a mixed method enquiry. PLoS One 2014;9:e115193.