East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2025;35:21-7 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2467

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Samara Hussain, Janet Hiu Ching Tse, Paul Wai Ching Wong, Mike Muk Yan Cheung, Rachel Ngan Yin Chan, Yun Kwok Wing, Steven Wai Ho Chau

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to determine the mental health status and help-seeking barriers and to identify predictors of help-seeking barriers among South Asians in Hong Kong at the end of the COVID- 19 pandemic.

Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and August 2023. Using convenience sampling, South and Southeast Asian Hong Kong residents aged ≥18 years were invited to complete an online questionnaire in English. Anxiety in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7. Depression in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Insomnia in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index. Perceived barriers to help-seeking were measured using eight statements; responses were either ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’. Additionally, quality of life and quality of health were assessed using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100.

Results: Of 474 respondents, 273 were verified to be South or Southeast Asians and were included in the analysis. Of these, 13.6%, 22.8%, and 12.1% were at risk of developing anxiety, depression, and insomnia, respectively. Self-report quality of life and quality of health scores were 70.3 and 67.9, respectively. Compared with those not at risk, those at risk of developing mental health disorders (anxiety, depression, or insomnia) were younger (34.0 vs 29.6 years, p = 0.003), not married (27.7% vs 43.6%, p = 0.02), and had lower quality of life score (77.3 vs 52.6, p < 0.001) and quality of health score (75.4 vs 49.1, p < 0.001). They also more frequently reported having cultural/language barriers (50.2% vs 70.5%, p = 0.004), having cost concerns (64.1% vs 80.8%, p = 0.011), being too busy to seek help (41.5% vs 66.7%, p < 0.001), and that their family considered having mental health disorders to be shameful (25.1% vs 51.3%, p < 0.001). The predictors of perceived barriers to help-seeking were full-time employment (p = 0.02), having a lower education level (p = 0.02), and being at risk of developing mental health disorders (p = 0.02).

Conclusion: Among South Asians in Hong Kong, those who were younger and not married were more likely to be at risk of developing mental health disorders, whereas males, full-time workers, those with a lower education level, and those at risk of developing mental health disorders were more likely to report having help-seeking barriers. The predictors of perceived barriers to help-seeking were full-time employment, a lower education level, and being at risk of developing mental health disorders.

Key words: Help-seeking behavior; Mental health; South Asian people

Samara Hussain, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Janet Hiu Ching Tse, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Paul Wai Ching Wong, Department of Social Work and Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Mike Muk Yan Cheung, Multicultural, Rehabilitation and Community Service, Hong Kong Christian Service, Hong Kong SAR, China

Rachel Ngan Yin Chan, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Yun Kwok Wing, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Steven Wai Ho Chau, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Address for correspondence: Dr Samara Hussain, Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: samarahussain@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 30 December 2024; Accepted: 3 February 2025

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of mental health issues increased worldwide, particularly among ethnic minorities. In Hong Kong, those from ethnic minority backgrounds often lack physical and psychological resources owing to language and cultural barriers and lower socioeconomic status. Pandemic control measures such as social distancing, home-schooling, and the closure of community centres hinder effective coping1 and adversely affect mental health.2-4 South Asians (ie, Pakistani, Indian, Nepali, and Bangladeshi) represent the largest ethnic minority group in Hong Kong.5,6

For ethnic minority families, stable income from multiple elementary jobs is crucial for fulfilling basic expenses and supporting family members in their home country.7 In Hong Kong, the unemployment rate rose from 2.8% in 2019 to 7.2% in 2020 and was significantly higher among ethnic minorities.8 The suspension of flight services also prevented ethnic minorities from attending funerals in their home countries.9

Being homebound increases family conflicts and worsens parent-child relationships due to parental stress, particularly in low-income families.2,10,11 Discrimination against virus carriers and a lack of multilingual COVID-19 updates also lead to uncertainty.12,13 At peak pandemic stages, most mental health services from non-governmental organisations were suspended.14

Mental health issues are more prevalent among those of lower socioeconomic status and from ethnic minority backgrounds.15,16 Among Hong Kong Chinese, 3 months after the first confirmed COVID-19 case, 19% had depression and 14% had anxiety, based on a cutoff score of >9 for the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), respectively.17

This trend was also observed in the United Kingdom and the United States.18,19 Among those with depression, 23.8% were of lower income and 11.2% were of higher income, whereas among those with anxiety, 22.5% were of lower income and 9.3% were of higher income.19 In the United States, compared with White people, the age-adjusted odds ratio for having depression symptoms nearly every day (a PHQ-2 score of ≥3) was 1.21 for Black people and 1.23 for Hispanic people.3 Among Hong Kong South Asians, 72.6%, 12.9%, and 14.5% had moderate, severe, and extremely severe depression, respectively; similarly, 52.3%, 16.1%, and 31.6% had moderate, severe, and extremely severe anxiety, respectively.4

Poor sleep is a risk factor and an early sign of mental health disorders.20 During the pandemic, the pooled prevalence of insomnia reached 23.87% worldwide.21 In Hong Kong, the prevalence of insomnia was 33.6% in April 2020,22,23 whereas 62.8% reported poor sleep quality between August and October 2021; quarantine was associated with sleep disturbances.24 In the United Kingdom, the prevalence of sleep loss was 24.7% overall and 32.0% among ethnic minorities.25 In the United States, Black people had 4.3 times higher odds of having severe insomnia (Insomnia Severity Index [ISI] ≥22) owing to income loss or unemployment.26 Ethnic minorities are disproportionately burdened by insufficient and poor- quality sleep.27,28

Ethnic minorities face mental health inequalities, which were accentuated during the pandemic.14 Factors of such inequalities can be individual, family, social, cultural, and institutional. Individual factors consist of interpretation of mental health issues, expression of such needs, lack of such information, and poor access to such services. Spirituality is commonly used to conceptualise mental health.29,30 Emotions and feelings are not fully expressed because they are considered shameful. Family and peers, despite being components of social support and coping, may hinder help-seeking and service utilisation. In Hong Kong, during the early stages of the pandemic, being single or divorced, having lower perceived knowledge of COVID-19, and having worries about losing job were predictive of higher levels of anxiety, depression, and/or stress, whereas being male, having a low monthly household income, and having worries about losing job were predictive of higher level of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.4

Stigma towards mental health and discrimination against ethnic minorities hinder help-seeking and access to mental health services.29 Culturally adapted counselling services may cater the needs of ethnic minorities.31 This study aimed to determine the mental health status and help-seeking barriers and to identify predictors of help-seeking barriers among South Asians in Hong Kong at the end of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January and August 2023. Using convenience sampling, South and Southeast Asian Hong Kong residents aged ≥18 years were invited to complete an online questionnaire in English (interpretation was available upon request) via booths in Yau Tsim Mong Districts. Compensation in terms of a HK$50 supermarket coupon was provided.

Anxiety in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the GAD-7. The seven items are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day); total scores range from 0 to 21: 0-4 (minimal), 5-9 (mild), 10-14 (moderate), and 15-21 (severe). A cut-off score of ≥10 was defined as at risk.

Depression in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the PHQ-9. The nine items are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day); total scores range from 0 to 27: 0-4 (minimal), 5-9 (mild), 10-14 (moderate), 15-19 (moderately severe), and 20-27 (severe). A cut-off score of ≥10 was defined as at risk.32

Insomnia in the prior 2 weeks was assessed using the ISI.33 The seven items are rated on a five-point Likert scale; total scores range from 0 to 28: 0-7 (none), 8-14 (subthreshold), 15-21 (moderate), and 22-28 (severe).34 A cut-off score of ≥15 was defined as at risk.

Perceived barriers to help-seeking were measured using eight statements; responses were either ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’. Additionally, quality of life and quality of health were assessed using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100.

Results

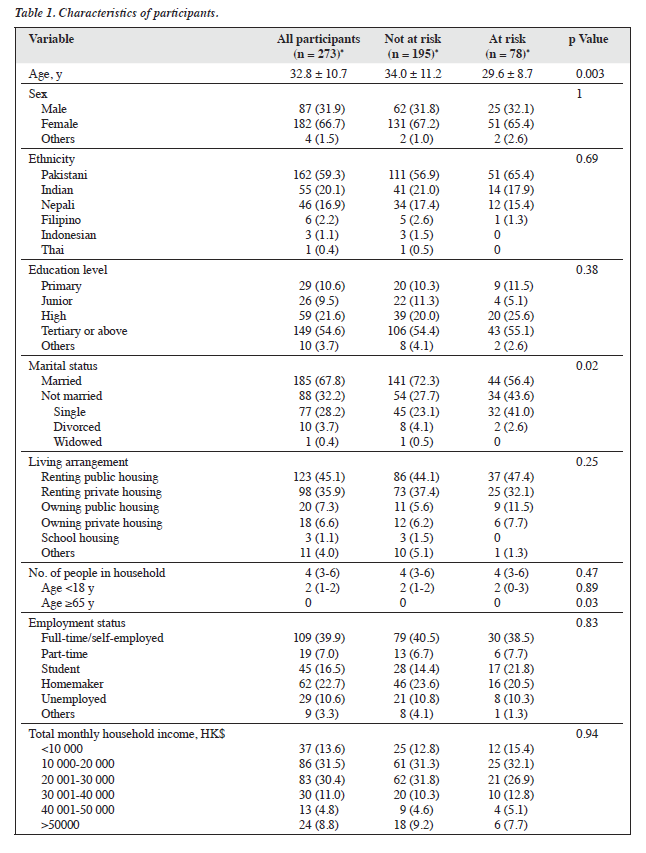

Of 474 respondents, 273 were verified to be South or Southeast Asians and were included in the analysis (Table 1). Our sample differed significantly with the population in the 2021 Census35 in terms of ethnic groups (p < 0.001) and age groups (p < 0.001). Our sample over-represented Pakistani (59.3% vs 17.5%) and under-represented Filipino (2.2% vs 18.8%), Indonesian (1.1% vs 6.4%), Thai (0.4% vs 8.2%), Indian (20.1% vs 27.8%), and Nepalese (16.9% vs 21.3%). Additionally, our sample over-represented those aged 15 to 24 years (27.8% vs 11.4%) and those aged 25 to 44 years (59.0% vs 34.4%) and under-represented those aged 45 to 64 years (12.5% vs 25.8%) and those aged ≥65 years (0.7% vs 8.6%). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.92 for the GAD-7, 0.90 for the PHQ-9, and 0.90 for the ISI.

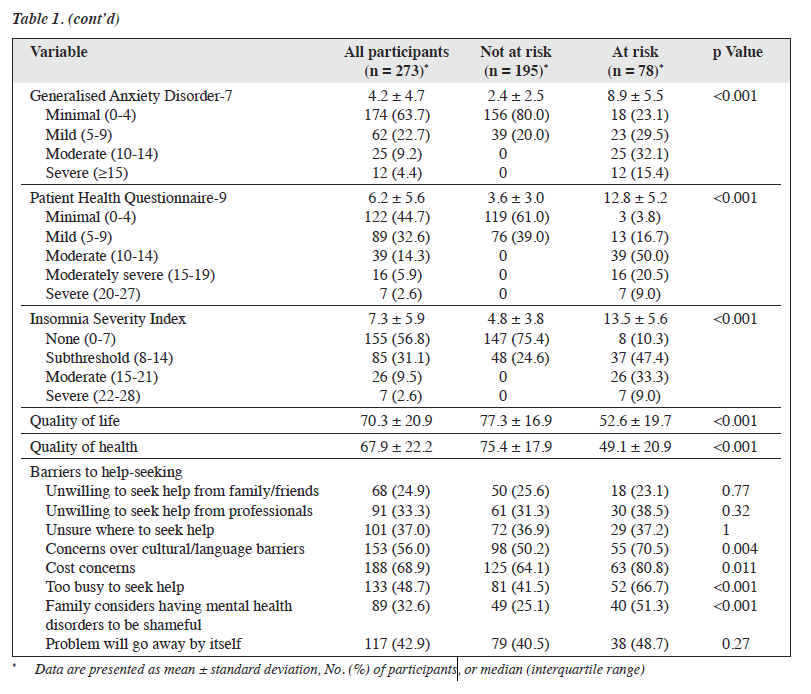

Of the participants, 13.6%, 22.8%, and 12.1% were at risk of developing anxiety, depression, and insomnia, respectively. Self-report quality of life and quality of health scores were 70.3 and 67.9, respectively. Regarding perceived barriers to help-seeking, 24.9% to 33.3% agreed that they were unwilling to seek help from family/friends or professionals; 37.0% were unsure where to seek help; 56.0% agreed having cultural/language barriers; 68.9% agreed having cost concerns; 48.7% agreed being too busy to seek help; 42.9% believed that the problem would go away by itself; and 32.6% agreed that having a mental health disorder would be considered shameful by their family.

Compared with those not at risk, those at risk of developing mental health disorders (anxiety, depression, or insomnia) were younger (34.0 vs 29.6 years, p = 0.003), not married (27.7% vs 43.6%, p = 0.02), and had lower quality of life score (77.3 vs 52.6, p < 0.001) and quality of health score (75.4 vs 49.1, p < 0.001). They also more frequently reported having cultural/language barriers (50.2% vs 70.5%, p = 0.004), having cost concerns (64.1% vs 80.8%, p = 0.011), being too busy to seek help (41.5% vs 66.7%, p < 0.001), and that their family considered having mental health disorders to be shameful (25.1% vs 51.3%, p < 0.001) [Table 1].

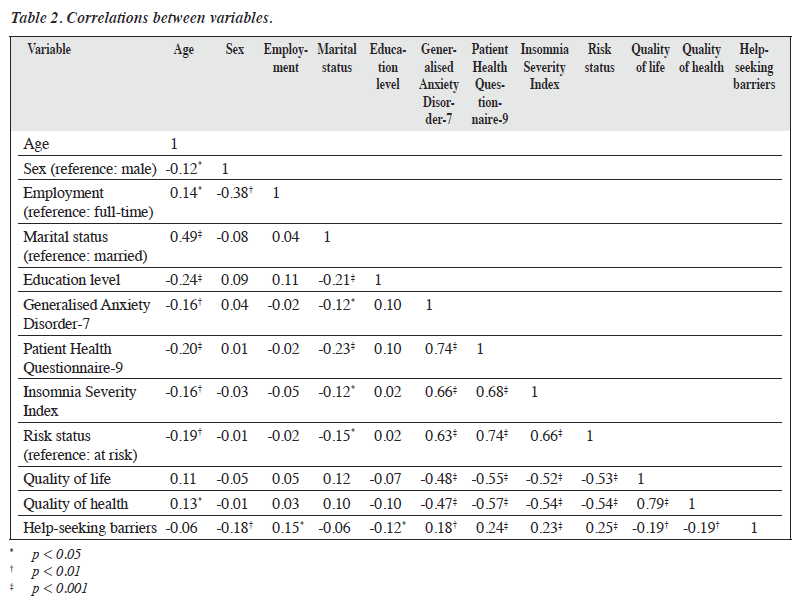

In the Pearson correlation analysis, those who were younger and not married were more likely to be at risk of developing mental health disorders, whereas males, full- time workers, those with a lower education level, and those at risk of developing mental health disorders were more likely to report having help-seeking barriers (Table 2).

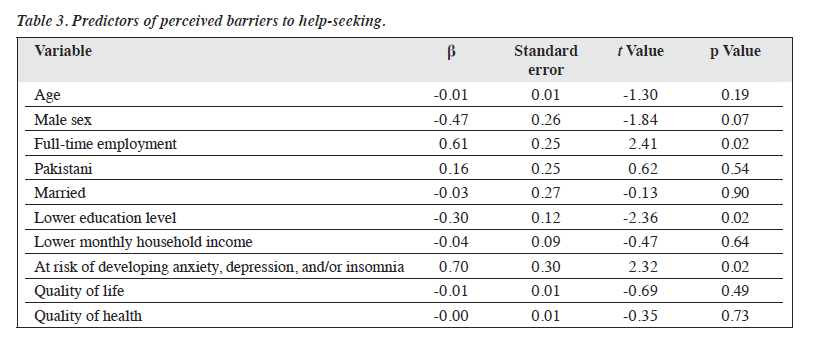

In the multiple regression analysis, after controlling for age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, total monthly household income, quality of life, and quality of health, predictors of perceived barriers to help-seeking were full- time employment (p = 0.02), having a lower education level (p = 0.02), and being at risk of developing mental health disorders (p = 0.02) [Table 3]. These predictors explained 14.3% (adjusted R2 = 0.11) of the variance (F(10, 248) = 4.135, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Compared with the early stages, at the end of the pandemic, the prevalence of anxiety remained at 13.6%, but the prevalence of depression slightly increased from 19.8% to 22.8%.17 Approximately one-third of the participants were at risk of developing one or more mental health disorders; depression was more common than anxiety and sleep problems. Those at risk tended to be younger and not married and had more help-seeking barriers (cultural and/ or language barriers, cost concerns, being too busy to seek help, and their family considering mental health issues to be shameful). Younger South Asians have constantly evolving roles and responsibilities and therefore are subject to additional pressures.3,4,30 In Hong Kong, there are double stigmas towards ethnic minorities and mental health disorders,29 as well as a lack of culturally sensitive and language barrier-free mental health services.30 South Asians may face employment difficulties due to language barriers; they often work in elementary or labour-intensive jobs, and the nature of these jobs can be stressful and cause mental health issues,36 leaving limited time for self-care. In Hong Kong public hospitals, the cost per attendance is HK$60 (US$7.66) for psychiatric services and HK$180 (US$22.99) for accident and emergency services.37 South Asians may be unfamiliar with the psychiatric services that are available in the public sector. Additionally, long waiting times38 and cultural and/or language barriers may limit their help-seeking.

To address the help-seeking barriers, culturally sensitive, multilingual information about access to mental health services, fees and charges, and mental health education should be provided. Immediate attention is needed for those who are too busy (ie, those in full-time employment) to seek help. Workplace mental health programmes can be organised, which may include mental health awareness, stress management, work-life balance promotion (eg, flexibility in working hours, paid leave for mental health issues, short breaks for praying), and promotion of a culturally sensitive working environment. The availability of mental health service is limited; District health centres should customise mental health support elements and improve their promotion to those from ethnic minority backgrounds. Mental health service providers should recruit more frontline staff or peer support workers from minority backgrounds to facilitate more effective communication and education. Multilingual digital platforms can be used to minimise time and cost concerns, as well as language and cultural barriers.39 For example, the Salamat platform is a multilingual online platform for mental health screening and referrals.40

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design cannot establish causality or capture changes over time. Pakistani people were over-represented; this limits the generalisability of findings to the other South Asian populations in Hong Kong. The self-report assessment tools may differ from the clinical evaluation by psychiatrists.

Conclusion

Among South Asians in Hong Kong, those who were younger and not married were more likely to be at risk of developing mental health disorders, whereas males, full-time workers, those with a lower education level, and those at risk of developing mental health disorders were more likely to report having help-seeking barriers. The predictors of perceived barriers to help-seeking were full- time employment, a lower education level, and being at risk of developing mental health disorders.

Contributors

SWHC designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SH acquired the data, analysed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JHCT designed the study. MMYC acquired the data. YKW, RNYC, and PWCW critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding / support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Survey and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (reference: SBRE-22-0238). The participants provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- Wang P. Struggle with multiple pandemics: women, the elderly and Asian ethnic minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. PORTAL J Multidiscip Int Stud 2020;17:14-22. Crossref

- Chung RY, Lee TT, Chan SM, et al. Experience of South and Southeast Asian minority women in Hong Kong during COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int J Equity Health 2023;22:110. Crossref

- Nguyen LH, Anyane-Yeboa A, Klaser K, et al. The mental health burden of racial and ethnic minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One 2022;17:e0271661. Crossref

- Wong CL, Leung AWY, Chan DNS, et al. Psychological wellbeing and associated factors among ethnic minorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Immigr Minor Health 2022;24:1435-45. Crossref

- Census and Statistics Department. Snapshot of Hong Kong Population- Ethnic minorities. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://www.census2021.gov.hk/doc/pub/21C_Articles_Ethnic_Minorities. pdf.

- Sung HM. Approaching South Asians in Hong Kong. Lingnan University. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cs_etd/12/.

- Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong Diocesan Pastoral Centre for Workers- Ethnic Minorities Service. Report on the employment situation of local ethnic minorities during the outbreak of Covid-19 epidemic. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://www.hkccla.org.hk/article/RI_20201120.pdf.

- Radio Television Hong Kong. Ethnic minorities severely affected by Covid. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://news.rthk.hk/rthk/en/component/k2/1657347-20220712.htm.

- Routen A, Darko N, Willis A, Miksza J, Khunti K. “It’s so tough for us now” — COVID-19 has negatively impacted religious practices relating to death among minority ethnic groups. Public Health 2021;194:146-8. Crossref

- Chan RCH. Dyadic associations between COVID-19-related stress and mental well-being among parents and children in Hong Kong: an actor-partner interdependence model approach. Fam Process 2022;61:1730-48. Crossref

- 1 Ho LLK, Li WHC, Cheung AT, Luo Y, Xia W, Chung JOK. Impact of poverty on parent-child relationships, parental stress, and parenting practices. Front Public Health 2022;10:849408. Crossref

- Arat G, Kerelian NN. The COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong: exploring the gaps in COVID-19 prevention practices from a social justice framework. Br J Soc Work 2023;53:1204-24. Crossref

- Lai DWL, Yu W, Lian C, Lam RYK. Experiences of South Asians in the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong. South Asian Diaspora 2024;16:19-34. Crossref

- Smith K, Bhui K, Cipriani A. COVID-19, mental health and ethnic minorities. Evid Based Ment Health 2020;23:89-90. Crossref

- Chau SWH, Hussain S, Chan SSM, et al. A comparison of sleep- wake patterns among school-age children and adolescents in Hong Kong before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Sleep Med 2023;19:749-57. Crossref

- Wong MC, Huang J, Wong YY, et al. Epidemiology, symptomatology, and risk factors for long COVID symptoms: population-based, multicenter study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2023;9:e42315. Crossref

- Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3740. Crossref

- Hall LR, Sanchez K, da Graca B, Bennett MM, Powers M, Warren AM. Income differences and COVID-19: impact on daily life and mental health. Popul Health Manag 2022;25:384-91. Crossref

- Jia R, Ayling K, Chalder T, et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040620. Crossref

- Palagini L, Hertenstein E, Riemann D, Nissen C. Sleep, insomnia and mental health. J Sleep Res 2022;31:e13628. Crossref

- Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2021;295:113599. Crossref

- Lam CS, Yu BY, Cheung DST, et al. Sleep and mood disturbances during the COVID-19 outbreak in an urban Chinese population in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study of the second and third waves of the outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:8444. Crossref

- Yu BY, Yeung WF, Lam JC, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances during COVID-19 outbreak in an urban Chinese population: a cross- sectional study. Sleep Med 2020;74:18-24. Crossref

- Fong TCT, Chang K, Ho RTH. Association between quarantine and sleep disturbance in Hong Kong adults: the mediating role of COVID-19 mental impact and distress. Front Psychiatry 2023;14:1127070. Crossref

- Falkingham JC, Evandrou M, Qin M, Vlachantoni A. Prospective longitudinal study of sleepless in lockdown’: unpacking differences in sleep loss during the coronavirus pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open 2022;12:e053094. Crossref

- Cheng P, Casement MD, Cuellar R, et al. Sleepless in COVID-19: racial disparities during the pandemic as a consequence of structural inequity. Sleep 2022;45:zsab242. Crossref

- Jackson CL, Johnson DA. Sleep disparities in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic highlight the urgent need to address social determinants of health like the virus of racism. J Clin Sleep Med 2020;16:1401-2. Crossref

- Yip T, Feng Y, Fowle J, Fisher CB. Sleep disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic: an investigation of AIAN, Asian, Black, Latinx, and White young adults. Sleep Health 2021;7:459-67. Crossref

- Yi Nam S, Yik Chun W, Tak Hing Michael W, et al. Double stigma in mental health service use: experience from ethnic minorities in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2023;69:1345-53. Crossref

- Kwan CK, Lo KC. Issues behind the utilization of community mental health services by ethnic minorities in Hong Kong. Soc Work Public Health 2022;37:631-42. Crossref

- Suen YN, Chen EYH, Wong YC, et al. Effects of a culturally adapted counselling service for low-income ethnic minorities experiencing mental distress: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial. BMJ Ment Health 2023;26:1-7. Crossref

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2019;365:l1476. Crossref

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011;34:601-8. Crossref

- Suh SA, Jeon H, Ong J. Diagnostic tools for insomnia. In: Kushida CA, editor. Encyclopedia of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. 2nd ed. Oxford: Academic Press; 2023: 140-8. Crossref

- 2021 Population Census. Hong Kong. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://www.census2021.gov.hk/en/main_tables.html.

- Ahmed K, Leung MY, Ojo LD. An exploratory study to identify key stressors of ethnic minority workers in the construction industry. J Constr Eng Manag 2022;148:04022014. Crossref

- Hospital Authority. Fees and Charges. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Parent_ID=10044&Content_ID=10045&Ver=HTML.

- Chan WC, Lam LCW, Chen EYH. Hong Kong: recent development of mental health services. BJPsych Adv 2015;21:71-2. Crossref

- The Legislative Council Subcommittee on Rights of Ethnic Minorities 8 May 2017 Meeting on “Difficulties encountered by ethnic minorities in gaining access to housing and healthcare services, and views on services provided by Support Service Centres for Ethnic Minorities” Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr16-17/chinese/hc/sub_com/hs52/papers/hs5220170508cb2-1315-4-c.pdf.

- Salamat. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Accessed 11 May 2024. Available from: https://cuhk.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/ SV_3aQJ4J8DcsNhVfU..