East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:114-21 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1824

THEME PAPER

Dr Bonnie WM Siu, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FRCPsych, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Oliver Chan, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Ms Cherie CY Au-Yeung, BSc, MStat, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Kavin KW Chow, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Amy CY Liu, MBChB, MRC Psych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Dorothy YY Tang, MBBS, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr SH Lui, MBBS, MRCPsych FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Eric FC Cheung, MBBS, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FRCPsych, Kwong Wah Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr M Lam, MBChB, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), Department of General Adult Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Bonnie WM Siu, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, 15 Tsing Chung Koon Road, Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong.

Email: bonniew114m@yahoo.com

Submitted: 6 March 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of mental illness in offenders referred to psychiatrists from January 2011 to March 2016 and any associations between crime and mental illness in these offenders.

Methods: Case notes of offenders referred to psychiatrists at the Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre from 1 January 2011 to 31 March 2016 were reviewed. Data on sex, age on admission, educational level, principal psychiatric diagnosis, index offence, source and reason of referral, and outcome were collected.

Results: Case notes were reviewed for 4492 offenders (75% males) aged 14 to 93 (mean, 40.6) years. Of these, 68% were referred by the courts for psychiatric report and 32% were referred by correctional institutions for psychiatric assessment and treatment. Approximately 73% of them had a diagnosable mental disorder. The most common principal psychiatric diagnoses were schizophrenia and related disorders (25%), mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (20%), and mood disorders (9%). The most common index offences were theft and related offences (22%), acts intended to cause injury (20%), and illicit drug offences (11%). Offences involving violence were more prevalent in males than in females (p < 0.001). In terms of the three most common principal psychiatric diagnoses, ‘acts intended to cause injury’ was most prevalent in those with ‘schizophrenia and other related disorders’ than in those with the other two diagnoses (31% vs 19% vs 17%, p < 0.001). ‘Theft and related offences’ was most prevalent in those with mood disorders than in those with other two diagnoses (38% vs 20% vs 18%, p < 0.001). ‘Illicit drug offences’ was most prevalent in those with ‘mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance’ than those with other two diagnoses (22% vs 8% vs 6%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions: The prevalence of mental disorders among offenders referred to psychiatrists is high. The pattern of associations between crime and mental disorders in these offenders is comparable with that reported in overseas studies. As Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre is the only facility in Hong Kong for mentally ill offenders, our sample is representative, and our results provide cross-sectional pattern of forensic psychiatric service utilisation in Hong Kong.

Introduction

Prevalence of mental illness in incarcerated population

Forensic psychiatry involves assessment and treatment of people with mental disorders who come into the legal system.1-3 In the incarcerated population, psychiatric morbidityhasbeen reported tobehighinboth remanded (63% of males and 76% of females) and sentenced (37% of males and 57% of females) prisoners.4-7 The estimated prevalence of severe mental illness in the incarcerated population has been reported to be 9% to 20%, compared with 6% in the general population.8-11 The increased prevalence is likely to be related to deinstitutionalisation, limited community resources, prominent court decisions and legislative rulings, and the ‘revolving door’ phenomenon.12,13 In a systematic review of 62 studies that included 23,000 prisoners from 12 countries, the prevalence of psychosis, major depression, and antisocial personality disorder was found to be several times higher in prisoners than in the general population.14

Relationship between crime and mental illness

The high prevalence of mental illness in remanded and sentenced populations could reflect the association between crime and mental illness (schizophrenia, personality disorder, depression, substance misuse, intellectual disability, and dementia). Patients with schizophrenia have been reported to be more likely to commit violent offences, although evidence on the association between schizophrenia and crime is conflicting.15 In a study in Sweden, the rate of violent offences was four times higher in schizophrenia patients, although the overall crime rate of male schizophrenia patients was similar to that of the general population.16 There is a strong association between acute psychotic symptoms and violence, and psychotic symptoms account for most of the very violent behaviour.17,18 In the Dunedin birth cohort, the violence rate among those with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders increases five-fold (in those with criminal convictions) to seven-fold (self- reported).19

In the United Kingdom, up to 78% of prisoners have a personality disorder, with antisocial personality disorder being the most common, followed by paranoid (in men) and borderline personality disorders (in women).20 In a systematic review of 62 studies about mental disorder in prisons, 65% of male prisoners had a personality disorder and 47% had a dissocial personality disorder.14

The typology of depressed shoplifters includes isolated young adults under stress and older people with chronic depression, depression associated with acute loss, and personality disorder with an aggressive swing.21,22 Similarly, shoplifting in middle-aged women is associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, particularly if shoplifting is the sole conviction.22

Substance misuse, combined with mental illness or personality disorder, is common among forensic psychiatric patients.20Alcohol and drugs may be associated with criminal behaviour because intoxication can impair judgement and reduce inhibition. In withdrawal states, agitation and psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia, can predispose one to violent behaviour. Additionally, various forms of theft are committed to purchase illicit substances. Substance misuse is more prevalent in individuals with personality disorder, and alcohol misuse is associated with increased violence in people with antisocial personality disorder.23

A meta-analysis of sex offenders reported strong association between low intelligence and paedophilic sex offences, but not for other types of sex offences.24 A case series reported that 11% of those charged with arson had learning disability.25 In a retrospective review of 2397 patients in memory and ageing centre, the common manifestations of criminal behaviour in patients with frontotemporal dementia were theft, traffic violations, sexual advances, trespassing, and public urination, whereas patients with Alzheimer dementia commonly committed traffic violations.26

Forensic psychiatric services

Prisons are left to deal with inmates whose behaviour does not reach admission criteria to psychiatric services despite ‘being marked enough to interfere with discipline and communication’.27,28 The provision of forensic psychiatric services varies considerably among countries and is governed by different mental health laws.1,29-31 In United Kingdom, forensic psychiatric services are delivered through high-security psychiatric hospitals, medium- security psychiatric units, low-security psychiatric units, community forensic mental health teams, and independent private secure psychiatric facilities, whereas admission and transfer are governed by the Mental Health Act.32

In Hong Kong, admission and transfer to psychiatric units are governed by the Mental Health Ordinance.33 Hong Kong has no high-security psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric criminals are taken to the Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre (SLPC) of the Correctional Services Department and cared for by outreach services provided by the Forensic Psychiatric Department of Castle Peak Hospital. The SLPC is the only facility of its kind in Hong Kong. It receives mentally ill offenders sentenced by the courts for compulsory psychiatric inpatient treatment, as well as remanded and sentenced individuals who require psychiatric assessment and treatment referred by courts and correctional institutions. In recent years, the number of new cases seen at the SLPC by visiting psychiatrists has been approximately 1100 to 1300 per year.

Objectives

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of mental illness in offenders referred to psychiatrists at the SLPC from January 2011 to March 2016 and any associations between crime and mental illness in these offenders.

This retrospective review study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the New Territories West Cluster of the Hospital Authority and the Research and Ethics Committee of the Correctional Services Department. Case notes at the SLPC from 1 January 2011 to 31 March 2016 were reviewed. Data on sex, age on admission, educational level, principal psychiatric diagnosis, index offence, source and reason of referral, and outcome were collected. For offenders with multiple admissions, only data from the latest admission were used. Psychiatric diagnosis was made within 2 weeks. Each case was discussed in the weekly clinical case round chaired by senior psychiatrists and a consensus was reached on the principal diagnosis (if any) based on the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases.34 The index offences were classified into 16 categories using the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification.35

Two-sample t test was used to compare the age between sex groups. Pearson’s Chi square test was used to determine any difference in the distribution of principal diagnosis, index offence, and reason for referral between sex groups. Cramer’s V was computed to assess the strength of association. If the distribution of a variable differed significantly between sex groups, the same test was repeated for sub-items. Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS (version 12.0; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). An alpha value of <0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

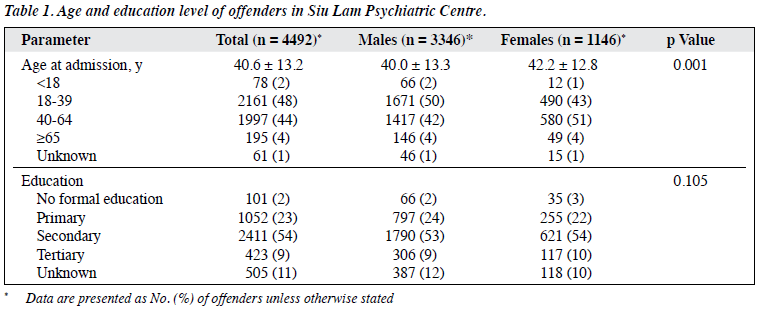

Case notes of 4492 offenders (75% males) aged 14 to 93 (mean, 40.6; standard deviation, 13.2) years were reviewed. Male offenders were younger than female offenders (40.0 ± 13.3 years vs 42.2 ± 12.8 years, p = 0.001, Table 1). Among males, the proportion of the age group of 18 to 39 years was larger than that of the age group of 40 to 64 years (50% vs 42%), but the distribution was reversed among females (43% vs 51%). Most (54%) offenders had secondary-level education.

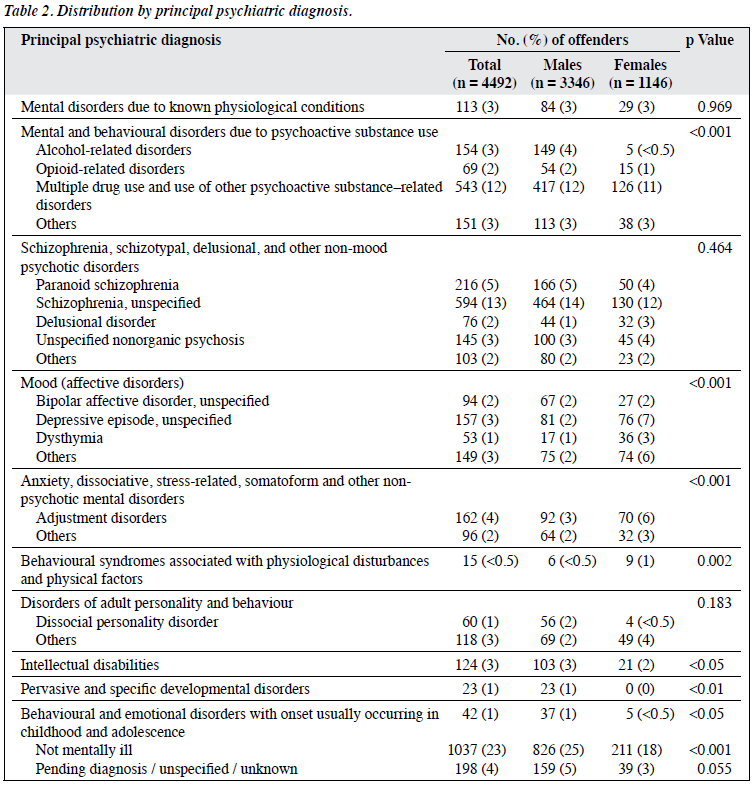

The distribution of principal diagnosis differed significantly between sexes (p < 0.001, Table 2), with a moderate association between principal diagnosis and sex (r = 0.210). Of all cases, 73% had a diagnosable mental disorder (70% in males and 79% in females). The most common diagnosis was ‘schizophrenia, schizotypal, delusional, and other non-mood psychotic disorders’ (25%), followed by ‘mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use’ (22% in males vs 16% in females, p < 0.001), especially for alcohol-related disorders (4% vs <0.5%, p < 0.001). Heroin was the most commonly used substance. ‘Mood (affective) disorder’ was more prevalent in females than males (19% vs 7%, p < 0.001), as was ‘anxiety, dissociative, stress-related, somatoform and other non-psychotic mental disorders’ (9% vs 5%, p < 0.001). Dissocial personality disorder and paraphilic disorders, such as exhibitionistic disorder and fetishism, were more prevalent inmales, whereas borderline personality disorder was more prevalent in females. The prevalence of ‘intellectual disabilities’, ‘pervasive and specific developmental disorders’, ‘behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence’, and ‘behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors’ was higher in males than in females (p < 0.05). ‘Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors’ was the least prevalent diagnosis, which was more common in females than in males (p < 0.05).

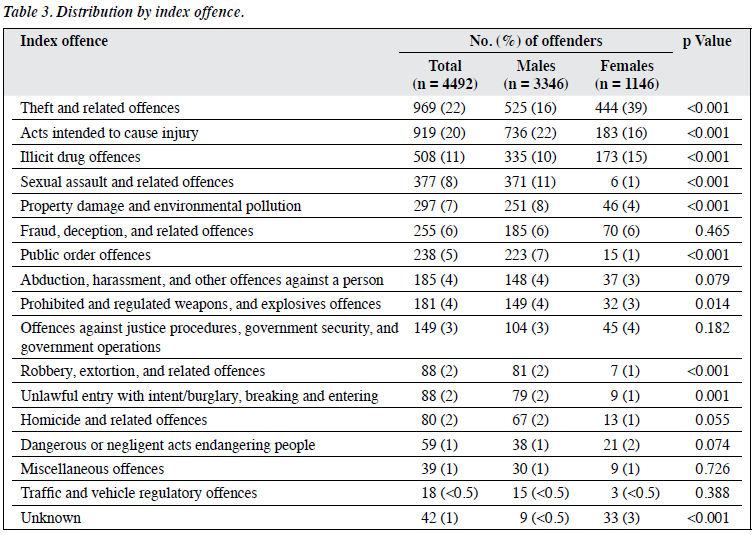

The distribution of the index offence differed significantly between sexes (p < 0.001, Table 3), with a strong association between index offence and sex (r = 0.342). ‘Theft and related offences’ was the most prevalent (39% in females vs 16% in males, p < 0.001), followed by ‘acts intended to cause injury’ (16% vs 22%, p < 0.001) and ‘illicit drug offences’ (15% vs 10%, p < 0.001). Offences involving violence, such as ‘sexual assault and related offences’, ‘property damage and environmental pollution’, and ‘public order offences’, were more prevalent in males than females (p < 0.001).

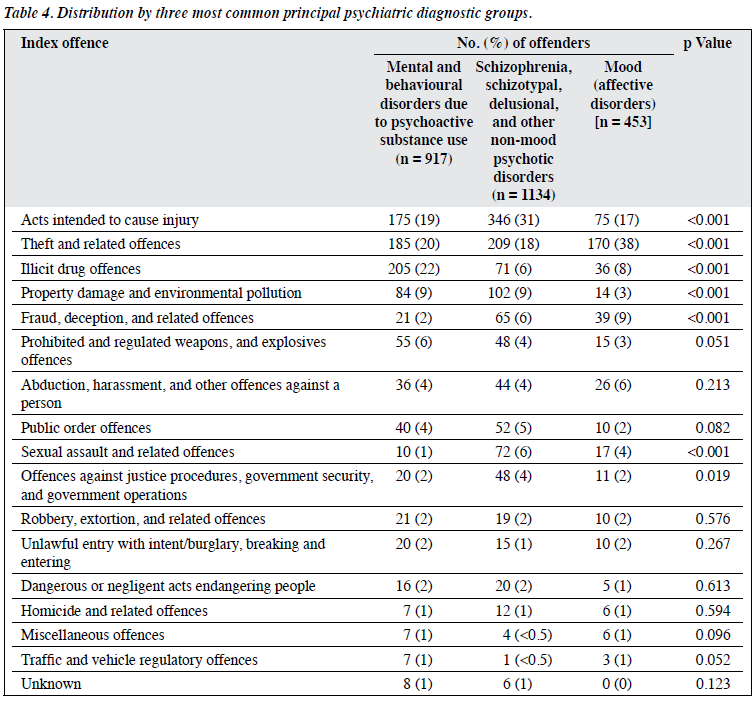

The three most common principal psychiatric diagnoses were moderately associated with ‘acts intended to cause injury’, ‘theft and related offences’, ‘illicit drug offences’, ‘property damage and environmental pollution’, ‘fraud, deception, and related offences’, and ‘sexual assault and related offences’ (r = 0.257, p < 0.001, Table 4). ‘Acts intended to cause injury’ was most prevalent in those with ‘schizophrenia and other related disorders’ than in those with other two diagnoses (31% vs 19% vs 17%, p < 0.001).

‘Theft and related offences’ was most prevalent in those with mood disorders than in those with other two diagnoses (38% vs 20% vs 18%, p < 0.001). ‘Illicit drug offences’ was most prevalent in those with ‘mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance’ than those with other two diagnoses (22% vs 8% vs 6%, p < 0.001).

Of the 4492 offenders, 1446 (32%) were referred by correctional institutions for psychiatric assessment and treatment, most commonly for ‘depressed mood’ (15%) and ‘psychotic symptoms’ (16%), whereas 3046 (68%) were referred by the courts for psychiatric report: 2763 (91%) by the Magistrates’ Courts, 214 (7%) by the District Court, and 67 (2%) by the High Court. The distribution of principal diagnosis differed significantly between the two types of referral (p < 0.001), with a strong association between principal diagnosis and type of referral (r < 0.332). Those referred by correctional institutions had a higher proportion of ‘disorders related to substance abuse and dependence’. ‘Self-harm’ and ‘suicidal tendency’ were more common in males (27%), younger age groups (25%), and illicit drug offenders (30%), whereas ‘unstable emotion’, ‘aggressive behaviour’, and ‘bizarre behaviour’ were more common in females (p < 0.02). About 48% of the offenders required no psychiatric follow-up, whereas 38% required psychiatric follow-up. Those referred by courts had a higher proportion of ‘schizophrenia and related disorders’. The most common outcome of psychiatric report was ‘ordinary sentence with psychiatric follow-up’ (46%), followed by ‘hospital order (compulsory psychiatric inpatient treatment)’ (25%) and ‘ordinary sentence without psychiatric follow-up’ (25%).

Discussion

Offender characteristics

Of all people arrested in Hong Kong during 2011 to 2015, 72% of males and 28% of females were arrested for indictable offences, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.54 to 1.36 For people aged <40 years, the percentage was 59% in males and 48% in females. In the United Kingdom in 2009, <20% of arrests were for females,37 whereas in the United States in 2010, approximately 25% of arrests were for females.38

In Hong Kong during 2011 to 2016, the most common offences for which males were arrested were ‘burglary and theft’ (29%), ‘violent and sexual offences’ (28%), and ‘serious drug offences’ (8%).39 For females, the most common offences were ‘burglary and theft’ (54%), ‘violent and sexual offences’ (14%), ‘fraud and forgery’ (9%), and ‘serious drug offences’ (6%).

The sex ratio for those at the SLPC was 2.91 to 1, which was higher than that in the arrested population. In females, the proportion of the age-group 40 to 64 years was higher than the younger age groups. This could be explained by the nature of SLPC, as only offenders with suspected mental health problems were referred to SLPC. The distribution of crimes by sex and age groups was confounded by the prevalence of mental illnesses in different sex and age groups, in different crimes, and in custodial populations, as well as differences in classification of offences.

Mental disorders among offenders

In the present study, 73% of offenders at SLPC (79% in males and 70% in females) had a diagnosable mental disorder, comparable to other studies.4,6,7 Remanded prisoners have a higher risk of mental disorder because of multiple factors, such as adjustment issues in relation to incarceration and prison environment, stresses from ongoing court proceedings and uncertainties about the offence and potential sentence and consequences, withdrawal from drugs and alcohol, dependence, and drug-induced psychosis.

Schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders

‘Acts intended to cause injury’ was associated with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, although ‘theft and related offences’ was also prevalent in schizophrenia, consistent with other studies.15-19 The proportion of homicides committed by people with psychosis is consistent across countries. Nevertheless, in our study, 12 (15%) of 80 of the ‘homicide and related offences’ were perpetrated by people with a schizophrenia- spectrum disorder, compared with 5% to 8% in Caucasian populations.40 This could be explained by the low homicide rate in Hong Kong. In addition, not all people charged with homicide were psychiatrically assessed at SLPC.

Personality disorders

In our study, 3% of offenders had personality disorder; dissocial personality disorder was more prevalent in males, and borderline personality disorder was more prevalent in females, consistent with other studies.14,20 The low prevalence of personality disorders may be due to the retrospective review nature without structured diagnostic interviews. Moreover, only the principal diagnosis was collected; personality disorder as a secondary diagnosis was not counted and thus underestimated. Whether people with different ethnicities would attract a diagnosis of personality disorder may be a potential source of bias, but no conclusion could be drawn owing to methodological variations.41

Substance use disorders

In our study, the prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use was higher in males than females (22% vs 16%), particularly for alcohol-related disorders. Heroin was the most prevalent substance.42 There is an association between heroin use and criminal behaviour.43,44 In a review of aggressive behaviour in heroin users, aggression was more closely associated with personality factors.45 In United Kingdom, over a third of male prisoners have used cannabis, and cannabis dependence was associated with violence in the Dunedin birth cohort.46 Among offenders in SLPC, cannabis was not commonly used. In contrast, the number of methamphetamine abusers increased by 7% during 2013 to 2015. Methamphetamine use has been reported to be associated with violent crimes, although the causal relationship has not been established.47

Mood disorders

Acquisitive offending is associated with both mood disorders and female sex, consistent with other studies.21,22 Associations between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression, and self-reported violence are equally strong.48 Approximately 7% of perpetrators of homicide have a lifetime diagnosis of mood disorder.40 Homicide- suicide and infanticide have been reported to associate with depression.49 Among offenders in SLPC, 7.5% (6 out of 80) of those indicted for homicide or related offences were diagnosed with a mood disorder.

Other diagnosis

In our study, compared with those without intellectual disability, those with intellectual disability were associated with sexual offences (25% vs 8%, p < 0.01), but the number of sexual offenders with intellectual disability was too small for subgroup analysis.24,25 Similarly, those with intellectual disability were associated with arson (6.5% vs 1.9%, p < 0.01). In addition, those with dementia were associated with theft and related offences (46% vs 21%, p < 0.01), consistent with other study.26 Nonetheless, the number of dementia cases was too small for subgroup analysis.

Referrals for psychiatric assessment

Suicide and non-fatal self-harm in prisoners was 500% higher than in a matched population in England and Wales.6 Among offenders in SLPC, 25% were referred because of suicidal tendency and self-harm, with the referral rate higher in males. Remanded prisoners, especially young offenders, and those with a history of illicit drug offences are at higher risk of suicide tendency and self-harm. In the prison population of England and Wales, the male-to-female ratio of prison suicides was nearly 10 to 1, and half had at least one psychiatric diagnosis.6 Among offenders in SLPC, the male-to-female ratio was about 5 to 1. Nearly 75% referred by courts had a psychiatric diagnosis, and 25% of them required compulsory inpatient treatment (hospital order).

Clinical implications

The high prevalence of mental illness in the remanded and sentenced populations in Hong Kong highlights the importance of forensic psychiatric services for detection, assessment, treatment, and rehabilitation to improve clinical outcomes and prevent relapses. Introduction of high- security psychiatric hospitals as a long-term measure is suggested. Intermediate measures include implementation of interventional programmes in collaboration with the Correctional Services Department for those with high risk of re-offending. Strategies for prison suicide risk assessment and prevention especially for young male illicit drug offences should be implemented, as should interventional programmes for prisoners with substance misuse (such as motivational interviewing programmes) and violence risk assessment and management. In addition, both physical health and social problems affect mentally ill offenders’ ability to cope with life in prison, pre- and post-release.

Limitations

One limitation of our study is that only the principal psychiatric diagnosis was collected. Multiple diagnoses were common, especially in the remanded populations. Approximately 25% of males and 33% of females on remand had two or more psychiatric diagnoses.50 The number of offenders with psychiatric diagnosis might be underestimated, such as those with substance abuse dependence and personality disorder. Of the 4492 offenders in SLPC, 10% of data were missing and may have affected the real distribution of the variables. Longitudinal studies using structured clinical diagnostic interviews are warranted to further explore the association between mental illness and crime. Additional variables (eg, ethnicity and the number of previous offences) should have been collected to determine an association of cultural and behavioural factors with mental illness or crime.

Conclusions

The prevalence of mental disorders among offenders referred to psychiatrists is high. The pattern of associations between crime and mental disorders in these offenders is comparable with that reported in overseas studies. As Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre is the only facility in Hong Kong for mentally ill offenders, our sample is representative, and our results provide cross-sectional pattern of forensic psychiatric service utilisation in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the SLPC staff who provided assistance.

Declaration

All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Gunn J. Introduction: what is forensic psychiatry? Crim Behav Ment Health 2004;14(Suppl 1):S1-5. Crossref

- Mullen Forensic mental health. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:307-11Crossref

- Rogers P, Soothill K. Understanding forensic mental health and the variety of professional voices. In: Handbook of Forensic Mental Health. Soothill K, Rogers P, Dolan M, editors. Devon: Willan Publishing; 2008.

- Fazel S, Benning R, Danesh J. Suicides in male prisoners in England and Wales, 1978-2003. Lancet 2005;366:1301-2. Crossref

- Gunn J, Maden T, Swinton Mentally Disordered Prisoners. London: Institute of Psychiatry and Home Office; 1991.

- Humber N, Piper M, Appleby L, Shaw J. Characteristics of and trends in subgroups of prisoner suicides in England and Psychol Med 2011;41:2275-85. Crossref

- Maden A, Taylor CJ, Brooke D, Gunn J. Mental Disorder in Remand Prisoners. London: Institute of Psychiatry; 1995.

- Beck AJ, Maruschak LM. Mental health treatment in state prisons, 2000. US Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2001. Available from: http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=788. Accessed 1 Jul 2016.

- Diamond PM, Wang EW, Holzer CE 3rd, Thomas C, des Anges The prevalence of mental illness in prison. Adm Policy Ment Health 2001;29:21-40. Crossref

- Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:761-5 Crossref

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617-27. Crossref

- Talbott JA. Deinstitutionalization: avoiding the disasters of the past. 1979. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:1112-5. Crossref

- Yohanna Deinstitutionalization of people with mental illness: causes and consequences. Virtual Mentor 2013;15:886-91.

- Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder in 23000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 2002;359:545-50. Crossref

- Gelder M, Gath D, Mayou Forensic psychiatry. In: Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Gelder M, Gath D, Mayou R, Cowen P, editors. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

- Lindqvist P, Allebeck Schizophrenia and crime. A longitudinal follow-up of 644 schizophrenics in Stockholm. Br J Psychiatry 1990;157:345-50. Crossref

- McNiel DE, Binder RL. The relationship between acute psychiatric symptoms, diagnosis, and short-term risk of violence. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1994;45:133-7. Crossref

- Taylor Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:491-8. Crossref

- Wessely S. The Camberwell study of crime and schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33(Suppl 1):S24-8. Crossref

- Singleton N, Meltzer H, Gatward R. Psychiatric Morbidity among Prisoners in England and Wales (Office for National Statistics). London: Statistical Office; 1998.

- Gibbens TC. Shoplifting. Med Leg J 1962;30:6-19. Crossref

- Gibbens TC, Palmer C, Prince J. Mental health aspects of shoplifting. Br Med J 1971;3:612-5. Crossref

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Alcohol-Use Disorders: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011.

- Cantor JM, Blanchard R, Robichaud LK, Christensen Quantitative reanalysis of aggregate data on IQ in sexual offenders. Psychol Bull 2005;131:555-68. Crossref

- Rix A psychiatric study of adult arsonists. Med Sc Law 1994;34:21-34. Crossref

- Liljegren M, Naasan G, Temlett J, Perry DC, Rankin KP, Merrilees J, et al. Criminal behavior in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:295-300. Crossref

- Walker N, McCabe S. Crime and Insanity in England. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 1973.

- Senior J, Shaw J. Mental Healthcare in Prison. In: Handbook of Forensic Mental Health. Soothill K, Rogers P, Dolan M, editors. Devon: Willan Publishing; 2008.

- Almanzar S, Katz CL, Harry B. Treatment of mentally ill offenders in nine developing Latin American J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2015;43:340-9.

- Priebe S, Badesconyi A, Fioritti A, Hansson L, Kilian R, Torres- Gonzales F, et al. Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison of data on service provision from six European countries. BMJ 2005;330:123-6. Crossref

- Way BB, Dvoskin JA, Steadman HJ. Forensic psychiatric inpatients served in the United States: regional and system differences. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law 1991;19:405-12.

- Thomson L, et al. The forensic mental health system in the United Kingdom. In: Handbook of Forensic Mental Health. Soothill K, Rogers P, Dolan M, editors. Devon: Willan Publishing; 2008.

- Mental Health Ordinace (Chapter 136, Laws of Hong Kong). Available from: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

- World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva, World Health Organization; 1992.

- Australian and New Zealand Standard offence classification, 2011. Available from: http://abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1234.0. Accessed 1 Jul 2016.

- Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong. Crime and Justice Statistics on Persons Arrested for Crime by Age Group and Sex, 2016. Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/FileManager/EN/Content_1149/T08_01.xls. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

- Ministry of Justice. Statistics on women and the criminal justice system, 2010. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/217824/statistics-women-cjs-2010.pdf. Accessed 1 Jul 2016.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States 2010. Available from: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2010/crime-in- the-u.s.-2010. Accessed 1 Jul 2018.

- Census and Statistics Department of Hong Kong. Crime and Justice Statistics on Persons Arrested for Crime by Type of Offence and Sex, 2016. Available from: http://www.censtatd.gov.hk/FileManager/EN/Content_1149/T08_02.xls. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

- Hunt IM, Swinson AB, Flynn S, Hayes AJ, Roscoe A, Rodway C, et al. Homicide convictions in different age-groups: a national clinical J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2010;21:321-35. Crossref

- McGilloway A, Hall RE, Lee T, Bhui KS. A systematic review of personality disorder, race and ethnicity: prevalence, aetiology and treatment. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:33. Crossref

- Census and Statistics Department of Hong Drug abuse situation in Hong Kong in 2015. Available from: http://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B71608FC2016XXXXB0100.pdf. Accessed 1 Mar 2018.

- Kaye S, Darke S, Finlay-Jones The onset of heroin use and criminal behaviour: does order make a difference? Drug Alcohol Depend 1998;53:79-86. Crossref

- Maden A, Swinton M, Gunn J. A survey of pre-arrest drug use in sentenced prisoners. Br J Addict 1992;87:27-33. Crossref

- Hoaken PN, Stewart SH. Drugs of abuse and the elicitation of human aggressive behavior. Addict Behav 2003;28:1533-54. Crossref

- Arseneault L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor PJ, Silva Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort: results from the Dunedin Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:979-86. Crossref

- Tyner EA, Fremouw WJ. Relation of methamphetamine use and violence: a critical Aggress Violent Behav 2008;13:285-97. Crossref

- Swanson JW, Holzer CE 3rd, Ganju VK, Jono Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:761-70. Crossref

- Rosenbaum M. The role of depression in couples involved in murder- suicide and homicide. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1036-9. Crossref

- Mueser KT, Noordsky DL, Drake RE, Fox Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2003.