East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:88-94

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Joseph Pui-Yin Chung, MBBS, MRCPsych, FHKCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), IPT (Supervisor Level D), Comprehensive Child Development Service, Department of Psychiatry, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong, SAR China.

Address for correspondence: Dr Joseph Pui-Yin Chung, Department of Psychiatry, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong, SAR China.

Tel: (852) 2595 4358; Email: chungpy2@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 26 November 2014; Accepted: 24 December 2014

Abstract

Interpersonal psychotherapy is one of two evidence-based formal psychotherapies for perinatal mood disorders. It is a time-limited, non-transference / cognitive-based therapy that focuses on communication and social support and can be easily conducted in a perinatal clinic setting. There is limited patient access to interpersonal psychotherapy in Hong Kong because the therapy is not widely disseminated. This case report aimed to illustrate the principles and techniques of interpersonal psychotherapy in perinatal psychiatry, and to raise interest among mental health professionals in Hong Kong in this evidence-based treatment.

Key words: Depression, postpartum; Psychotherapy

Introduction

Perinatal mood disorders are common. In particular, women of childbearing age are at higher risk of developing depression.1 For major and minor depression, a point prevalence of 8.5% to 11.0% has been reported during pregnancy and 6.5% to 12.9% during the first-year postpartum.2 In Hong Kong, a prevalence of 6.4% has been reported for antenatal depression, and 1.4% for antenatal anxiety.3 Maternal mental disorders have been shown to be associated with behavioural, developmental, and emotional problems in children.4,5 Nonetheless intervention in postnatal depression, both pharmacological and non- pharmacological, affects child development positively.6

Despite the relative safety7 and efficacy8 of selected antidepressant use for perinatal mood disorders, some mothers are reluctant to take them because of concerns about their effect on the fetus or on breastfeeding. Some patients fail to respond to antidepressants alone and some benefit from a combination of antidepressant and psychological treatment. Thus psychotherapy clearly has a role in the management of perinatal mood disorders.

Both cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) have been shown to be effective in the management of patients with perinatal mood disorders in clinical trials. A Cochrane meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological interventions in patients with postnatal depression found benefit for CBT (risk ratio = 0.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.57-0.90) and for IPT (risk ratio = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.66-0.98) but not for psychodynamic therapy.8 Research also suggests that the 2 therapies are indicated for different patients and they work in different ways.9 Interpersonal psychotherapy is a time- limited, non-transference / cognitive-based therapy that focuses on communication and social support. It embraces a biopsychosocial, cultural, and spiritual model.10 Its treatment focus on interpersonal dispute, role transition, as well as grief and loss issues is particularly appropriate for common problems experienced by women during the perinatal period.

In Hong Kong, CBT is commonly used for the management of perinatal mood disorders while IPT is much less disseminated because of the lack of local training. It is lamentable that patients have limited access to this potentially useful treatment that is one of the two evidence- based psychological interventions currently available for perinatal mood disorders. In our perinatal psychiatric clinic at Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital in Hong Kong, around 30.8% of our patients with postnatal depression refuse prescription of an antidepressant. We routinely select suitable patients with perinatal mood disorders for weekly IPT for 12 to 16 weeks. The spectrum of disorders includes perinatal depression, perinatal anxiety disorders, and perinatal adjustment disorders. This case report aimed to disseminate the skill of IPT by illustrating the techniques used on a session-by-session basis in a patient with postnatal anxiety disorder.

The Case

The patient was a 31-year-old mother, married for 3 years with a planned pregnancy. She was referred by an on-site psychiatric nurse at the Anne Black Maternal and Child Health Centre because of an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale score of 22. She presented with persistent anxiety following delivery.

The patient developed anxiety during the antenatal period because of threatened miscarriage and a false-positive Down’s syndrome screening test result. She had a healthy non-Down’s syndrome baby boy, delivered by Caesarean section because of breech presentation. After her baby arrived, she described feeling that everything was in a mess and she felt confused. She was also unable to breastfeed and this added to her stress. She started developing marked anxiety symptoms with catastrophic thinking, e.g. her son might have heart disease as he grew up, and he might suddenly die. She even had nightmares of scenes in which her son died. She saw intrusive images of dropping her son on the ground, and as a result she avoided carrying him. She failed to sleep after expressing milk at 4 am. She experienced hyperventilation and tension headaches and was mildly depressed. She had vague suicidal ideas of jumping from a height at the peak of her anxiety. Although her husband was very supportive, she felt they did not spend enough time with each other since the birth. She repeatedly asked her husband for reassurance and her husband felt overwhelmed by her reassurance-seeking behaviour. She felt her husband did not express love to her and did not understand her needs. At the first session, she scored 9 (borderline) for depression and 18 (severe) for anxiety on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and 28 on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) [severe anxiety]. She did not want to be treated with antidepressants.

The patient had been seen by a counsellor while at secondary school and university because of situational stress. She had never sought treatment from a mental health team before. She enjoyed good physical health and had no family history of psychiatric illness. She was born in Hong Kong. Both of her parents were busy at work and seldom spent time with her. She described her father as being very strict and fierce. Her mother was a successful businesswoman and always asked her to think rationally without attending to her feelings. She also had an elder brother to whom she was close. She was psychologically and physically abused by a female domestic worker from newborn to 7 years old, although her parents were unaware of this due to long hours of working. Her domestic worker would beat her up, forced her to eat cockroaches, and even threatened verbally and by gestures to kill her. She was always fearful when she was a child and was totally submissive to her domestic worker. She emigrated to Canada when she started primary school. She expressed difficulty in maintaining trust in relationships as she grew up. While in Canada, her parents divorced. After graduation from university she returned to Hong Kong and worked as a secondary school teacher. She was married for 3 years but had difficulty trusting her husband despite his caring attitude towards her.

The patient described herself as a perfectionist. She was an anxiety-prone person and would panic when unexpected things happened. She had few close friends and had difficulty trusting others. Her only interest was shopping. She did not smoke or drink, and had never used illicit drugs.

She had lived in Canada for 20 years and felt herself to be more Canadian than local Hong Kong Chinese. She was able to speak Cantonese but was more fluent in English. She had returned to Hong Kong for 6 years but still had difficulty adjusting to the fast pace of life in Hong Kong. She was a non-practising Catholic and her Christian faith had minimal impact on her life.

Diagnosis: Postnatal Anxiety Disorder

Part I: Clinical Assessment

Clinical assessment is usually completed in the first 3 sessions and includes completing a standard psychiatric interview, interpersonal inventory, and interpersonal formulation. Goals are agreed with patients and the structure of IPT introduced. The aim is to establish the diagnosis, determine if the patient is suitable for IPT, assess the current social network and attachment style of the patient, and to identify areas of focus for intervention.

We carried out a standard psychiatric interview in session 1. Particular attention was paid to establishing a diagnosis, understanding her personality, especially with regard to her interpersonal relationships, and excluding factors that would make her unsuitable for psychotherapy, e.g. marked suicidal ideas.

In sessions 2 and 3, we assessed the patient’s attachment style, completed the interpersonal inventory and interpersonal formulation, and established goals of treatment. In particular, we tried to identify patterns of interpersonal interaction that had existed from a very young age. To understand her attachment style and the influence of her childhood, we asked open-ended questions. For example, “Tell me about your childhood”, “Tell me about your relationship with your parents”, “Tell me about your relationship with your siblings”, “How did you get along with others in school?”, “How did your parents discipline you?”, “When you did something good, would your parents praise you?”, “Did your parents encourage the expression of affection in the family?”, and “Tell me about your friends as you grew up”.

For the interpersonal inventory, we used a simple 3– concentric circle graphic representation of an interpersonal network10 (Fig 1). We handed her a piece of paper with 3 concentric circles on it and asked her to write down the names of 7 to 8 people in her support network.11 Then we asked her to describe the relationships. An important point to note is to have the patient write down the names, not the therapist. This simple exercise has a powerful effect: it helps the patient to open up and the therapist to understand the current social network of the patient, as well as her pattern of interpersonal relationships.

For this patient, her closest relationship was with her husband. She had an ambivalent relationship with her parents who often criticised her for being an incompetent mother. She had a very limited social network in Hong Kong.

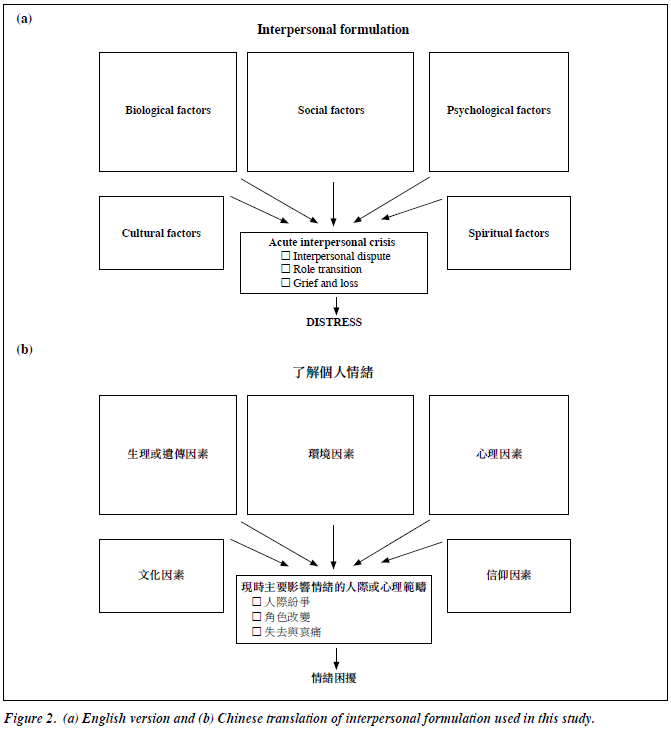

For interpersonal formulation, we employed a biopsychosocial, cultural, spiritual model as suggested by Stuart and Robertson.10 Again we handed her a piece of paper with boxes of different aetiological categories on it and asked the patient to fill in the boxes as guided by the therapist (Fig 2a). Some patients have difficulty understanding the difference between categories of aetiological factors and require an explanation by the therapist. Again it is important for the patient to write the factors down herself. The aim of the interpersonal formulation is to allow the patient to open up and to appreciate the many factors that contribute to her illness. According to Klerman et al,12 the founder of IPT, it is important in IPT to allow the patient to assume a “sick role”. This allows patients to receive in a compensatory but time- limited way the care that has not been adequately received — or felt as received — from others. It also helps them to understand that depression is a disorder wherein they are not fully in control but from which, with treatment, they will recover without serious residual damage, instead of taking a moral view of their illness that depression is a failure, a sign of weakness, a just punishment for past misconduct, or even a deliberate act.12 We have also translated the interpersonal formulation into Chinese for use in local patients (Fig 2b).

The patient identified a number of factors causing her depression: miscarriage symptoms as a biological factor, recent home moving as a social / environmental factor, susceptibility to stress / worry as a psychological factor, and the stressful environment in Hong Kong as a cultural factor. The identification of various contributing factors to her anxiety shifted the blame away from herself. She identified interpersonal dispute with everyone, especially her husband, and role transition with the expectation to be a good mother as the focus for IPT treatment. It is worthwhile to note that she had a fearful attachment style according to the IPT model.10 This had implications for treatment because she would likely be fearful of establishing friendships, expanding her social network, and communicating with her husband as the therapy progressed. She may also fear expressing thoughts and feelings towards her therapist, thus a lot of encouragement and good rapport building was essential.

Treatment goals were set with the patient, and included helping her husband understand her more by improving her verbal communication with him, and inviting people to accompany her out with baby with the eventual goal of taking baby out by herself. When establishing goals with patients, they will often talk about very broad goals such as “I want to be happier”. Such goals are not very useful as a focus in treatment and the therapist needs to guide the patient into achievable interpersonal goals, e.g. 30 minutes’ quality time with husband each week.

To conclude the first 3 sessions, it is important to establish a good rapport with the patient in the initial assessment sessions so that the patient will trust the therapist when entering the work phase of IPT.

Part II: Middle Sessions — Work Phase

Common techniques used in the work phase include clarification to understand the patient’s experience, exploration of interpersonal incidents, detailed analysis of communication, problem solving, encouragement for expression of affect, and role playing.10 According to Rafaeli and Markowitz,13 it is important to help the patient acknowledge her emotions and to experience them more deeply, and to help her understand emotion as a response in an interpersonal context and then to communicate the feeling to improve an important relationship.13 Progress is achieved by helping the patient to verbalise feelings in an interpersonal context within the session and to practise the skills outside the sessions.

Typically in IPT, instead of asking “How have you been last week?” to start a session, we asked “How have you been working on your relationships?” to maintain an interpersonal focus in treatment.10

In session 4, the patient chose to start working on the interpersonal dispute with her husband. The therapist asked her to describe in detail a recent interpersonal incident with her husband. She reported an incident in which her husband wanted her to teach in a better school for the sake of her son’s easy admission to that school, but she felt too stressed about changing jobs. The technique of clarification was used to clarify important details about triggering factors of the conflict, how the couple resolved the conflict, and what happened to them afterwards. Detailed communication analysis between the couple was conducted to clarify the typical patterns of interaction. She was encouraged to express her feelings within the session and the therapist adopted a non-judgemental approach. An important question to ask her was, “Do you think your husband understands you?”10 The feeling of not being understood by an important person in one’s life provides a powerful motivation to work on that relationship. She was encouraged to express her feelings towards her husband but she did not know how to do it. Exchange of feelings had never been a predominant way of communication between the couple. The technique of role playing was employed to empower her to express her feelings to her husband, and the technique of brainstorming was employed to find the right time to talk to her husband. Furthermore, a link was proposed by the therapist between the disputes and the ongoing feelings of anxiety. This provided a motivation for her to work on the disputes with the aim of reducing her anxiety.

In session 5, the therapist started the session by asking her, “How did it go when you tried to express your feelings of anxiety towards your husband about changing school?” She reported that she had ruminated for the whole week about how to talk to her husband, but finally mustered the courage to do so because she felt it was a homework assigned by the therapist that she needed to complete. After expressing her feelings of anxiety to her husband, her husband immediately said it was alright if she decided not to change job. She had never imagined that such a simple expression of affect could result in a very positive response from her husband. She felt an immediate reduction in her anxiety and interestingly the reduction in anxiety helped her child care. She could now hold her baby, something she could not do before because of her fear of dropping him. The therapist took the chance to consolidate her gain by linking the improvement in mood and in child care ability to the courageous step she took in expressing her feelings to her husband. Then the patient reported her husband had failed to have eye contact with her when they talked and that this had affected her mood. The therapist encouraged her to use the previous techniques to express her feelings towards her husband. Again role playing was carried out in the session.

In session 6, the patient reported that her mood became anxious spontaneously because of bad weather. She was generally tense with free-floating worrying thoughts and autonomic features of arousal. She did not do the homework for the week because she was feeling down. In CBT, the therapist would typically review the negative cognitions with the patient. Nonetheless IPT is non–cognitive-based, so anxiety symptoms were not explored. Instead the therapist discussed with her again the link between interpersonal disputes and anxiety and role play about how to express her feelings to her husband.

In session 7, the patient did not focus on her feelings of anxiety but talked to her husband about giving her eye contact. Her husband immediately agreed and reassured her she could tell him her feelings anytime and he would attend to them. Her mood improved and her anxiety was reduced. With the reduction in anxiety and improvement in her relationship with her husband, she was even planning to go on a vacation with her husband and leave her son in the care of her domestic worker.

In sessions 8 to 10, the therapist continued to work on the interpersonal disputes between the patient and her husband by using techniques such as communication analysis, brainstorming, and role play. The patient reported occasional setbacks in communication in which her husband shut off communication with her and she would respond by avoidance with a consequent increase in anxiety. The therapist tried to point out patterns of interpersonal interaction to the patient and helped her develop ways to overcome such dysfunctional patterns. Ideally her husband would have been invited for several conjoint sessions but in this case the busy schedule of her husband’s job did not permit this. Having achieved success in working on the disputes with her husband, the therapist went on to work on the disputes between the patient and her parents. Role transition was introduced briefly by exploring with the patient the good and bad aspects in her old and new role, and brainstorming with her about interpersonal ways to compensate for the loss in her new role, e.g. going out with her colleagues to regain her role as an independent woman. She also tried to expand her social network by reconnecting with her relatives and going out with them to shift her focus away from the stress in child care. Nonetheless role transition was not discussed in depth because she chose to focus mainly on the interpersonal disputes.

Part III: Concluding Sessions

In sessions 11 to 12, since the patient had a fearful attachment style, it was expected she might experience marked separation anxiety on completion of therapy. To reduce separation anxiety, the therapist employed several techniques. First, the therapist started each session by telling her the number of sessions they had done and how many sessions were left. This allowed the patient to anticipate the end of therapy. Second, maintenance sessions were conducted to space out the contact between the patient and her therapist. Third, the patient was reassured that if she had a relapse in her illness, she could return for acute treatment.

In the last 2 sessions, the patient had already adopted a new pattern of interpersonal communication and was familiar with the skill of communicating her thoughts and feelings to others confidently in appropriate settings. She could handle interpersonal disputes automatically with the new skills she had learnt through therapy. In session 12, much time was spent on reviewing her progress, congratulating her on her success, and attributing success to the efforts she made to improve communications and expand her social network. This is particularly important because in IPT the therapist serves as a coach to the patient,10 rather than an expert giving new insights. If the patient can internalise the therapeutic gain, she can employ similar techniques to deal with interpersonal situations in the future without depending on the therapist. In the last session, symptoms of relapse and anticipated future stress were discussed. Finally, the therapist discussed with the patient transition to maintenance sessions.

By session 12, the HADS score had reduced to 3 for depression and 7 for anxiety (compared with 9 for depression and 18 for anxiety at the beginning of therapy), and HAM-A score had reduced to 6 (compared with 28 at the beginning of therapy). The patient had also achieved the goal of improving verbal communication with her husband and taking baby out by herself.

Part IV: Maintenance Sessions

Maintenance sessions were conducted less frequently and for shorter periods of time. In this case, the maintenance sessions were scheduled every 2 weeks for 20 minutes with the intention of reducing separation anxiety and consolidating the therapeutic gains. New interpersonal incidents were discussed within the sessions and the patient was encouraged to apply what she had learnt during the acute treatment sessions to cope with the incidents. A link between mood change and improvement in communications and expansion of social network was again reinforced. By the end of the second maintenance session, the patient felt she had improved so much that further sessions were unnecessary. The therapist reassured her that resumption of acute treatment could be arranged anytime she felt the need.

Discussion

The above case illustrates the principles and techniques of IPT in perinatal patients. It is interesting to note that throughout therapy, the cognitions of anxiety and the significance of somatic symptoms of anxiety were not explored. In fact, only interpersonal relationships and social support were addressed, yet anxiety was still markedly reduced. Similar experiences have been reported in studies of IPT. For example, in a pilot study of IPT for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), the focus was on the interpersonal sequelae of PTSD rather than on its traumatic triggers and exposure techniques were not employed.13 The authors propose that IPT offers an alternative for patients who refuse (or do not respond to) exposure-based approaches.13

In our case scenario, the patient also found that the anxiety involved in exposure was unbearable, and the thought of exploring her catastrophic thinking about dropping her baby and the sudden death of her baby unacceptable. Interpersonal psychotherapy provided an acceptable way for our patient to work with the therapist. Some patients who are less cognitively orientated also find discussing important relationships appealing and more fitting to their concept.

Although we used a case of postnatal anxiety disorder in this case illustration, therapists can modify the techniques when applying IPT to other perinatal mood disorders. Interpersonal psychotherapy has been empirically tested in patients with postnatal depression and shown to be efficacious.14 Pilot studies of IPT have been carried out for panic disorder15 and PTSD13 in a non-perinatal setting and preliminary results are encouraging. Since anxiety and PTSD can occur in a perinatal setting, IPT may also have a role in these. Interpersonal psychotherapy has not been tested in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. In using IPT in a perinatal setting, case selection will be important. Patients need to be willing to come back for weekly psychotherapy and this may not be easy, especially during the busy postnatal period. They also need to be willing to practise interpersonal communications in between sessions as most of the gains in IPT actually occur outside of the therapy sessions. It has also been suggested that CBT may be more suitable than IPT for depressive patients with greater clinical severity (Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale score of ≥ 30),16 co-morbid personality disorder,9 and the presence of avoidance attachment.17

Interpersonal psychotherapy is suitable for practice by experienced mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, mental health social workers, and occupational therapists. Interpersonal psychotherapy is also suitable in the primary care setting.10 Experienced psychotherapists can perform IPT competently to a high level after as little as one supervised case.18 The International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy19 supports the guidelines for IPT training to become a certified therapist that include participation in an IPT course lasting 2 days or more, followed by supervision of 4 completed cases of IPT by a certified supervisor with a minimum of an hour of supervision per 2 hours of therapy, based on audio or videotaped recordings of sessions. Further training opportunities can be found at the Interpersonal Psychotherapy Institute20 or other institutions that provide accredited IPT training.

We hope the above case report serves as an introduction to the use of IPT in perinatal psychiatry in Hong Kong and encourages mental health professionals to receive training in this potentially useful therapy.

Declaration

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Burke KC, Burke JD Jr, Rae DS, Regier DA. Comparing age at onset of major depression and other psychiatric disorders by birth cohorts in five US community populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:789-95.

- Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: summary. 2005 Feb. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 1998-2005.

- Lee DT, Chan SS, Sahota DS, Yip AS, Tsui M, Chung TK. A prevalence study of antenatal depression among Chinese women. J Affect Disord 2004;82:93-9.

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR. Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:1134-41.

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Maternal depression and child development. Paediatr Child Health 2004;9:575-83.

- Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Ross L, Smith WC, Helms PJ, Williams JH. Effects of treating postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction and child development: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:378- 86.

- Udechuku A, Nguyen T, Hill R, Szego K. Antidepressants in pregnancy: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:978- 96.

- Dennis CL, Hodnett E. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(4):CD006116.

- Joyce PR, McKenzie JM, Carter JD, Rae AM, Luty SE, Frampton CM, et al. Temperament, character and personality disorders as predictors of response to interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:503-8.

- Stuart S, Robertson M. Interpersonal psychotherapy: a clinician’s guide. 2nd ed. CRC Press; 2012.

- Stuart S, Schultz J, McCann E. Interpersonal psychotherapy clinician handbook. IPT Institute; 2012.

- Klerman GL, Weissman MM, Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depression. New York, US: Basic Books; 1984.

- Rafaeli AK, Markowitz JC. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for PTSD: a case study. Am J Psychother 2011;65:205-23.

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:1039-45.

- Lipsitz JD, Gur M, Miller NL, Forand N, Vermes D, Fyer AJ. An open pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for panic disorder (IPT-PD). J Nerv Ment Dis 2006;194:440-5.

- Luty SE, Carter JD, McKenzie JM, Rae AM, Frampton CM, Mulder RT, et al. Randomised controlled trial of interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:496-502.

- McBride C, Atkinson L, Quilty LC, Bagby RM. Attachment as moderator of treatment outcome in major depression: a randomized control trial of interpersonal psychotherapy versus cognitive behavior therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2006;74:1041-54.

- Rounsaville BJ, Chevron ES, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, Frank E. Training therapists to perform interpersonal psychotherapy in clinical trials. Compr Psychiatry 1986;27:364-71.

- International Society for Interpersonal Psychotherapy. Available from: http://interpersonalpsychotherapy.org/. Accessed 20 May 2015.

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy Institute. Available from: https://iptinstitute.com/. Accessed 20 May 2015.