East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2018;28:144-9 | DOI: 10.12809/eaap1834

THEME PAPER

Dr Amy CY Liu, MBChB (CUHK), FRCPsych (UK), FHKAM(Psych), FHKCPsych, Department of Forensic Psychiatry, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong

Address for correspondence: Dr Amy CY Liu, 1/F, Block F, Castle Peak Hospital, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong.

Tel: 24567111; Fax: 24631644; Email: lcy715@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 6 April 2018; Accepted: 31 July 2018

Abstract

This commentary discusses law reform on diminished responsibility in the United Kingdom and provides a personal perspective on forensic psychiatric practice relating to diminished responsibility in Hong Kong.

Key words: Expert testimony; Homicide

Introduction

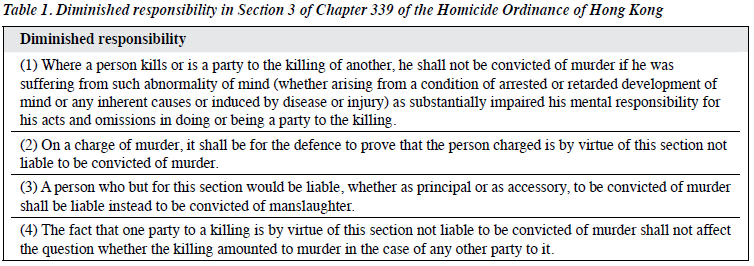

In 1957, the plea of diminished responsibility was introduced into English law as Section 2 of the Homicide Act 1957 of the United Kingdom (UK). In 1963, it was adopted in Hong Kong and listed in Section 3 of Chapter 339 of the Homicide Ordinance (Table 1). After 1997, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’s judiciary continues to follow the common law system. This statute remains effective since, and up till now, the plea of diminished responsibility operates under its ambit in our local judiciary system.

In October 2010, the UK Parliament has implemented a series of reforms in homicide laws. The old statute on the partial defence of diminished responsibility had been criticised as out-of-date and not taking into account the recent advancements and medical discoveries of modern psychiatry.1,2 In response to that, the UK Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 (1) to (1B) was introduced to address the problems of the Homicidal Act 1957 Section 2. Since then, there is an important discrepancy between the homicide laws of Hong Kong and the UK.

This article aims at drawing the attention of our profession to the laws related to diminished responsibility in Hong Kong. The article provides an in-depth discussion of the partial defence of diminished responsibility, the effect of the Homicide Ordinance 1963 Section 3 on forensic psychiatric practice in Hong Kong, and compares the local statute with the new UK law in diminished responsibility. It is noteworthy that our discussion focused mainly on the perspective of forensic psychiatrists and might have overlooked many important arguments from other professions and subspecialties. Nevertheless, we believe that more attention and discussion on this important area is needed, and it would be conducive if medical and legal professions and the public can further discuss what and how the law on diminished responsibility in Hong Kong should progress and develop in the future.

Partial defence of diminished responsibility

Diminished responsibility is a partial defence to murder but not to other offences. If successful, the charge of murder is reduced and a defendant is convicted of manslaughter. A conviction of murder inevitably results in a mandatory life sentence as stated in Offences against the Persons Ordinance Chapter 212 Section 2. The diminished responsibility plea provides an opportunity for the defendant to circumvent the serious penalty of life sentence. Unlike the M’Naghten rule that has a very stringent legal definition and negates the mens rea of murder, the diminished responsibility plea can be successful even if the defendant has an established mens rea of murder. Moreover, unlike the M’Naghten rule that results in an acquittal, the partial defence of diminished responsibility only allows reduction of offence. The plea of diminished responsibility can only be raised by the defence and must be proven on the balance of probabilities. In case both the prosecution and defence agree with the partial defence of diminished responsibility, the agreement will be put forward to the trial judge. If the judge agrees and the facts are clear, the defendant will be convicted of manslaughter without trial and sentenced to a wide range of options, at the discretion of the judge, from life imprisonment to non- custodial sentences. If either side of the prosecution or defence disagrees with the partial defence of diminished responsibility, a formal trial will proceed.

“Abnormality of mind”

Three years after the introduction of diminished responsibility under the Homicide Act 1957, the definition of “abnormality of mind” was first laid down by case law in R v Byrne,3 in which a sexual psychopath killed a female victim when he experienced sexual impulse that was difficult to control. At the Court of Appeal, Lord Chief Justice Parker defined “abnormality of mind” as “a state of mind so different from that of ordinary human beings that the reasonable man would term it abnormal. It appears to us to be wide enough to cover the mind’s activities in all its aspects, not only the perception of physical acts and matters and the ability to form a rational judgment whether an act is right or wrong, but also the ability to exercise willpower to control physical acts in accordance with that rational judgment.” The ruling had a significant impact on the scope of “abnormality of mind” in the diminished responsibility plea.

“Arising from a condition of arrested or retarded development of mind or any inherent causes or induced by disease or injury”

The Court of Appeal in R v Dix4 stated that “all forms of mental abnormality that can be used within the section, and that medical evidence is essential and without psychiatric evidence the plea under diminished responsibility is not possible.” According to the above interpretation of the statute, various conditions have been accepted to qualify the partial defence of diminished responsibility, including paranoid psychosis (R v Sanderson),5 paranoid personality disorder (R v Martin),6 battered woman syndrome (R v Ahluwalia),7 chronic alcoholism resulting in brain damage (R v Tandy),8 and irresistible perverted sexual desires (R v Byrne).3

“Substantially impaired the mental responsibility”

In R v Lloyd,9 “substantial” is interpreted as “less than total but more than trivial”. In 2014, the Court of Appeal further stated that “substantial” is not merely more than trivial or minimal in R v Golds.10 The Court of Appeal pointed out that judges should not provide explanation of the term “substantial” unless being asked to do so. Nonetheless, there has not been clear guidance from the Court regarding the meaning of “mental responsibility”. Conventional understanding refers “mental responsibility” to moral responsibility rather than legal responsibility. In R v Khan,11 it is emphasised that it is the decision of the jury when the question of “mental responsibility” is considered.

Reform in the partial defence of diminished responsibility in the UK

In the UK, the law on the partial defence of diminished responsibility in Homicide Act 1957 Section 2 had been criticised as a statute that was “out-of-date” and failed to evolve with advancement of modern medical science. The Law Commission in the UK launched an open consultation to obtain feedback on the proposed reforms on the law of murder. Notably, the Commission published two reports, ie, Partial Defences to Murder and Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide, in 2004 and 2006 respectively. The Commission and the public concluded that law reform was necessary. The resultant changes on the law of diminished responsibility emerged in the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52(1) to (1B) [Table 2]. The Homicide Act 1957 Section 2(1) was repealed accordingly.

The new law differs from the old law in the following aspects:

- The defendant has to be suffering from an abnormality of mental functioning instead of an abnormality of mind.

- The abnormality of mental functioning has to arise from a recognised medical condition.

- Cases of diminished responsibility should demonstrate substantial impairment of the ability to understand conduct, to form a rational judgment, or to exercise self-control.

- The abnormality of mental functioning is required to provide an explanation, or a significant contributory factor for killing.

“Abnormality of mental functioning”

In the Law Commission report Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide,2 Lord Justice Buxton criticised the definition of abnormality of mind in the old law as “disastrous and beyond redemption”. First, “abnormality of mind” is not a psychiatric term (at least not acommonly used terminmodern psychiatry), and therefore its meaning has to be developed by the Court from case to case. The term “abnormality of mind” has been used to refer to many different psychiatric conditions ranging from paranoid psychosis to irresistible perverted sexual desire. Many of these “conditions” do not fit into diagnostic entities of modern psychiatric classification systems. Second, the old law attempted to include all possible “causes” of “abnormality of mind” (ie, “arising from a condition of arrested or retarded development of mind or any inherent causes or induced by disease or injury”). The attempt to include all possible causes has been challenged, because modern medical evidence suggests that a psychiatric condition usually originates from multiple possible “causes” (or aetiological factors) stemming from the interaction between genetic vulnerability and life events. Lastly, psychiatrists generally preferred the term abnormality of mental functioning to abnormality of mind.

“Arose from a recognised medical condition”

The UK Law Commission believes that this change would prevent the law from being constrained by a set of “fixed and out-of-date causes” from which an abnormality of mental functioning must stem. Rather, the concern is whether the abnormality is brought about by a recognised medical condition. This requirement is supposed to ensure that the partial defence of diminished responsibility is supported by a valid medical diagnosis. Although the new law does not make explicit indication, it in effect requests medical experts to make reference to internationally recognised diagnostic systems (ie, the ICD-1012 and the DSM-513). It is believed that such approach would prevent individual psychiatrists from making “idiosyncratic diagnoses”, and therefore would set a higher standard on expert evidence.

“Substantial impairment of defendant’s ability to understand conduct, to form a rational judgement, or to exercise self-control”

In the UK old law, “substantial impairment of one’s mental responsibility” is required for the partial defence of diminished responsibility, and this is a decision to be made by the jury. As stated in the UK Law Commission report, the old law did not explain in what way the effect of an abnormality of mind can reduce the culpability for an intentional killing. As a result, the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 (1A) laid down the requirement and specified that “substantial impairment” should affect the ability to understand the conduct, to form a rational judgement, or to exercise self-control. Whereas the previous “substantial impairment of mental responsibility” referred to moral responsibility, the new law stated a clearer direction to medical experts (psychiatrists) to focus on the assessments of specific capacities of mental functioning. This would probably help to free psychiatrists from the need to consider the non-medical aspect of morality. The new law helps to clarify the role of medical experts and the role of the jury, and more clearly delineates the roles of the two parties.

Under the new law, medical experts are to provide opinion on (1) whether the defendant is suffering from an abnormality of mental functioning stemming from a recognised medical condition and; (2) whether and in what way the abnormality as such has an impact on the defendant’s capacities to understand the conduct, to judge, and to exercise self-control. On the other hand, the ultimate issue, ie whether the impairment is substantial, would be the jury’s decision, after learning from the medical experts’ evidence regarding the defendant’s relevant mental capacities.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists (UK) believed that the new law could prevent the jury from floundering with materials and issues with which they are not in a position to cope. Medical experts are allowed to inform the jury about the likely effects of the defendant’s psychiatric disorder on his/her various mental capacities, without the need to comment on the “ultimate issue”, ie, whether these amount to substantial impairment of mental responsibility.2

Abnormality of mental functioning is required to provide an explanation for killing

The Law Commission Report 2006 stated that there were conflicting opinions regarding this requirement of abnormality of mental functioning.2 Legal experts advised against the introduction of a strict causation requirement. However, the Royal College of Psychiatrists (UK) did not object to this new requirement but cautioned against the possible situations that medical experts might be called to “demonstrate” the causal relationship scientifically. This concern is related to the inherent difficulty in psychiatry to infer “biological” causation between behaviour and mental symptoms/functioning. After considering the suggestions in the Law Commission Report, the UK government decided that a stronger requirement on the aspect of causal relationship is necessary, such that the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Subsection 1B clearly states that the abnormality of mental functioning has to provide an explanation, or at least being a significant factor for defendant’s conduct.

Criticisms

The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 brought a radical change to the old UK law on the partial defence of diminished responsibility. The new UK law has significantly narrowed down the availability of diminished responsibility to murder cases, by making more stringent requirements to the previous loosely defined conditions satisfying partial defence. Several legal experts in the UK14 criticised the new law for making the partial defence of diminished responsibility much more difficult to attain, with a threshold higher than the insanity defence, and thus might defeat the purpose of the pleas of diminished responsibility, which is to provide a way for the mentally ill defendant to avoid the serious sentence of life imprisonment. Others criticised that the requirement of “abnormality in mental functioning to impair ability to understand one’s conduct” appeared to overlap with the second arm of the requirement of the insanity defence.15 Lastly, the attempt in the new law to define “abnormality of mental functioning” according to medical diagnosis has been criticised as a shortcoming which might limit the jury’s flexible approach to make judgement according to humanistic consideration and moral standard.14

Murder cases remanded to Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre in Hong Kong

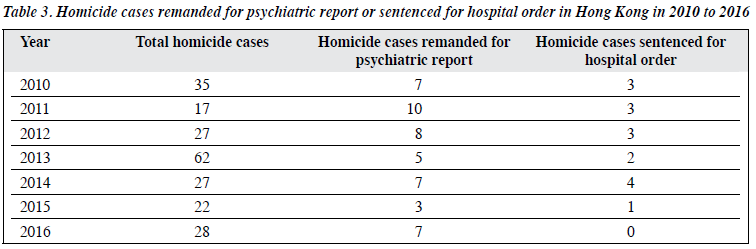

In Hong Kong, psychiatric opinion will be sought whenever the issue of diminished responsibility is raised in a murder case. The prosecution (ie, the Department of Justice) almost always seeks opinion from psychiatrists in the public sector. Defendants are usually refused bail by the Court, so the psychiatric assessment and compilation of reports are mostly carried out in a custodial centre. In Hong Kong, only Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre (SLPC) provides service on psychiatrist assessment and preparation of reports by visiting psychiatrists. The service is provided by the forensic psychiatric department of Castle Peak Hospital. The database of SLPC is therefore able to capture all murder cases that

are remanded for preparation of psychiatric reports. Table 3 shows the number of homicide cases as reported by the Hong Kong Police Force from 2010 to 2016,16 and the number of homicide cases being remanded for psychiatric reports at SLPC and sentenced to serve hospital order in the respective years.

A personal view on the diminished responsibility plea from the perspective of a local forensic psychiatrist

As a forensic psychiatrist, the author has opportunities to assist the Court during the legal proceedings of serious criminal cases such as murder cases. Diminished responsibility is a frequently raised defence in these cases. A conviction of murder warrants mandatory life sentence, whereas a conviction of manslaughter allows the trial judge to pass different sentencing options. The diminished responsibility plea allows mentally disordered offenders to be circumvented from the mandatory life sentence, which was a death sentence in the past. When the partial defence of diminished responsibility is raised in a local Court, the case will be discussed in accordance with the Homicide Ordinance Section 3, which was directly adopted from the Homicide Act 1957, a law that was passed over 60 years ago. The author would like to share some personal experience on the difficulties encountered in Court when diminished responsibility is discussed. Furthermore, the author would like to discuss on whether the new Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 in UK could provide possible solutions to the above-mentioned difficulties.

Abnormality of mind (arising from a condition of arrested or retarded development of mind or any inherent causes or induced by disease or injury)

In the 1970s, a task force to revise the DSM was established, with Robert Spitzer as the chairman. Before that, the stability and validity of psychiatric diagnoses was under much criticism. Established in 1980, DSM-III is the first attempt to operationalise and standardise psychiatric diagnostic practices across different countries in the US and Europe. The vague terminology “abnormality of mind” in Homicide Ordinance Section 3 was laid down in 1957, much earlier than the development of the modern standardised diagnostic system. It is no longer commonly used in modern psychiatric practice. From a psychiatrist’s perspective, Lord Chief Justice Parker’s definition of “abnormality of mind” in the R v Byrne3 could not address this problem. For instance, the author was once asked by the Court to ignore the diagnostic criteria (DSM-5 and ICD-10) that are universally used by our profession. However, modern psychiatrists are trained medical experts to make specific diagnosis according to these diagnostic classification systems, which are based on scientific evidence. The outdated term “abnormality of mind” thus places psychiatrists in a difficult position in an attempt to explain to jury regarding the mental condition of a defendant.

The bracketed information tried to elaborate on the causes for “abnormality of mind”. The original intention to define “abnormality of mind” was to be as inclusive as possible. However, this “all-inclusive” approach has been criticised, as modern medical evidence suggests that a psychiatric condition usually originates from multiple possible “causes” stemming from the interaction between genetic vulnerability and life events. For example, commonly accounted psychiatric condition such as drug- induced psychosis is not included in the bracketed definition of Homicide Ordnance Section 3.

The UK new law appears to provide a viable solution to the above problems. The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 (1) replaced the wording “abnormality of mind” with “abnormality of mental functioning which arose from a recognised medical condition”. As commented by the Royal College of Psychiatrists of UK,2 it implies that a recognised diagnosis in one of the internationally recognised diagnostic classification systems is likely necessary to fulfil the requirement under this provision. The author welcomes this clarity in terminology, because this will improve standardisation and validity of psychiatric diagnosis raised in the Court for the plea of diminished responsibility.

“Substantially impaired his mental responsibility”

This legal concept (if there is an abnormality of mind, whether it substantially impairs the defendant’s mental responsibility in the killing) should be determined by the jury rather than by the experts. However, in daily practice, psychiatrists are often asked to comment on this “ultimate issue” of diminished responsibility plea. At the Court, it is not uncommon to see jury being drowned in loads of professional psychiatric opinions and terms, and the jury is likely not equipped with the necessary medical knowledge to understand this medical evidence to form an opinion as to whether there is a “substantial impairment on one’s mental responsibility”. “Mental responsibility” is typically understood as “moral responsibility” and this is not a medical concept. When asked to comment on the issue of “mental responsibility”, the expert is forced to make comments outside their area of expertise. Although the judge usually directs the jury that the ultimate decision is the jury to make but not the experts, forensic psychiatrists are usually reluctant to give a “yes-or-no” answer, as the opinions of authoritative figures (psychiatrists) will unavoidably influence a layperson’s (the jury) view. This results in blurring of the roles between the jury and the experts.

The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 52 (1A) specifies the capacities that should be impaired by the abnormality of mental functioning in order to make the diminished responsibility plea successful. With this provision, psychiatrists can provide expert opinion on whether the capacities are impaired without stretching the opinion out of their area of expertise to address the “ultimate issue”, ie whether the impairment is substantial. It helps in clarifying the role of the expert and the jury and avoids putting medical experts in a difficult position in Court.

Conclusion

The reform of the partial defence in diminished responsibility in UK renders a discrepancy in the relevant statute in Hong Kong and the UK. The discrepancy would likely affect the body of relevant case laws that can be used in the local legal proceeding on diminished responsibility plea in the future. The UK reform has substantially narrowed down the previous broadly defined requirement for the partial defence. Although the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 section 52 has caught up with the modern development of psychiatric medicine and has overcome shortcomings of the old laws, it is criticised for being too stringent and lacking flexibility. The experience of the UK reform could provide inspiration and reflection on the current situation in Hong Kong. Nevertheless, more studies by various professionals are necessary.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre and Correctional Service Department for providing service statistics. The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose and received no financial support for this study.

References

- Law Commission. Partial Defences to Murder: Final Report (Law Com No 290). The Stationery Office; 2004.

- Law Commission. Murder, Manslaughter and Infanticide. Project of the Ninth Programme of Law Reform: Homicide (Law Com No 304). The Stationery Office; 2006.

- R v Byrne (1960) 2 QB 396

- R v Dix (1982) CrimLR 302

- R v Sanderson (1994) 98 Cr.App.R 325

- R v Martin (1989) 1 AUUER 652

- R v Ahluwalia (1992) 4 AIIER 889

- R v Tandy (1989) 1 WLR 350

- R v Lloyd (1967) QB 175

- R v Golds (2014) EWCA Crim 748

- R v Khan (2009) EWCA 1569

- The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Eastman N, Adshead G, Fox S, Latham R, Whyte Legal tests relevant to psychiatry. In: Forensic Psychiatry (Oxford Specialist Handbooks in Psychiatry). 1st ed. Oxford University Press; 2012: 473-508. Crossref

- Mackay R. Mental Disability at the Time of the Offence. In: Gostin L, McHale J, Fennell P, Hugh W, Mackay RD, Bartlet, Principles of Mental Health Law and Policy. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010:721-56.

- Crime statistics in detail, homicide: 2007-2017. Hong Kong Police Force, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.