Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2001;11(3):13-17

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

GWL Chan, GS Ungvari, JP Leung

Dr GWL Chan, MN, PhD Candidate, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Dr GS Ungvari, PhD, FHKCPsych, FHKAM(Psych), FRANZCP, MRCPsych, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Dr JP Leung, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Address for correspondence: Dr GWL Chan, c/o Dr GS Ungvari Department of Psychiatry, 11/F, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin, Hong Kong, China

Submitted: 16 October 2000; Accepted: 6 August 2001

Abstract

Following the worldwide trend of de-institutionalisation, there has been a movement to shift the locus of care of patients with chronic psychiatric illness from hospitals to community-based residential services in Hong Kong. To date, 7 studies of community-based residential services for psychiatric patients in Hong Kong have been published. In this article, these studies are reviewed with an emphasis on the effectiveness of the rehabilitative efforts of community-based rehabilitation and on the outcome measures used in these studies. The results of these studies do not equivocally support the effectiveness of local residential services in psychiatric rehabilitation. Despite the fact that quality of life has been a widely used outcome measure in studies of deinstitutionalisation worldwide, quality of life as an outcome measure has not been extensively explored in local studies until recently. Therefore, further studies to investigate how local residential services affect the quality of life of psychiatric patients is required.

Key words: Psychiatric rehabilitation services; Quality of life; Schizophrenia

Introduction

De-institutionalisation began in the 1950s in most western countries with the aim of discharging psychiatric patients to less restrictive, community-based residential settings to reduce hospitalisation rates, enhance the effectiveness of rehabilitation, and reduce costs.1 However, the effect of de- institutionalisation on clinical outcome has been found to be equivocal.2,3

Recently, quality of life (QOL) has emerged as an important outcome indicator because it can give a more complete picture of community-based treatment inter- ventions than can clinical outcome measures such as changes in symptom prof ile or relapse rate.1 Moreover, QOL can be used to monitor the impact of de-institutionalisation on the lives of discharged long-stay psychiatric patients.4

Following the worldwide trend of de-institutionalisation, psychiatric services in Hong Kong have also started to shift the locus of care from hospitals to community-based settings.5 The main aim of social rehabilitation of psy- chiatric patients is to facilitate their reintegration into the community.6 Halfway houses (HWHs) and long stay care homes (LSCHs) are the 2 primary residential services providing rehabilitation for psychiatric patients who do not need intensive inpatient treatment but still need to acquire a variety of skills to adjust to the circumstances of independent life in the community.

The current trend in social rehabilitation in Hong Kong follows the prevailing western model by assuming that psychiatric patients have a better chance of recovery and a better quality of life outside hospitals. This article calls attention to the fact that while these assumptions are taken for granted, they have seldom been tested in Hong Kong.

This article briefly describes the social rehabilitation services for discharged psychiatric patients in Hong Kong and reviews local studies of the effectiveness of HWHs and LSCHs. The need to include quality of life as an outcome indicator in further studies conducted in community settings is also discussed.

Social Rehabilitation Services in Hong Kong

Social rehabilitation services have been in place since the f irst HWH was established in 1964.5 Since then, both the diversity and number of social rehabilitation services in Hong Kong have dramatically increased.

According to the Hong Kong Rehabilitation Program Plan, social rehabilitation services in Hong Kong have 3 components:6

- residential services (HWHs, LSCHs, supported hostels, and supported housing)

- activity centre for discharged psychiatric patients (day- care centre and social club)

- employment services (sheltered workshop and supported employment).

In December 1998, there were 570 places in LSCHs with 1258 psychiatric patients waiting for a place.6 1217 HWH places (442 in purpose-built facilities) were available with 396 psychiatric patients waiting for a place. There were 154 supported hostel and housing places for groups with various disabilities and 180 day-care centre and 800 social club places. In October 1996, there were 5535 sheltered workshop and 950 supported employment places.7

Judging by the number of places, HWHs and LSCHs are the 2 major residential components of social rehabilitation services in Hong Kong. Tremendous expansion is planned for the next 5 years because of the government’s intention to right size the 2 major psychiatric hospitals (Castle Peak Hospital [CPH] and Kwai Chung Hospital) and transform Lai Chi Kok Hospital into a LSCH.

The capacity of the LSCHs will increase from the existing 570 places to 1370 places by 2002/2003 and HWH places will increase from the current 1217 to 1417 during the same period.6 At least 1000 patients who currently live in hospital will be moved to community-based residential services, thereby increasing their importance in the re- habilitation of discharged psychiatric patients.

According to the Hong Kong Rehabilitation Program Plan, the main objective of the LSCHs is to maintain the stability of discharged patients and enable them to move towards independent living in the community.6 The main objective of the HWHs is to train discharged patients to reach their optimal functioning, thereby facilitating their reintegration into the community.6

This is an ambitious plan, the success of which hinges on whether these community settings can fulf il their missions. In an attempt to answer this question, local studies examining HWHs and LSCHs will be reviewed in the following sections.

Review of Community Residential Settings in Hong Kong

Because of a lack of a centralised index of local studies, the source of information for this review includes only the following sources:

- Hong Kongiana database

- papers which have been presented at meetings during the past 5 years

- 2 local journals (Hong Kong Journal of Mental Health and Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry).

Only studies relating to the effectiveness of HWHs and LSCHs are included in this review. Studies relating to public attitudes towards these psychiatric residential services and the condition of people discharged from HWHs will not be discussed here.

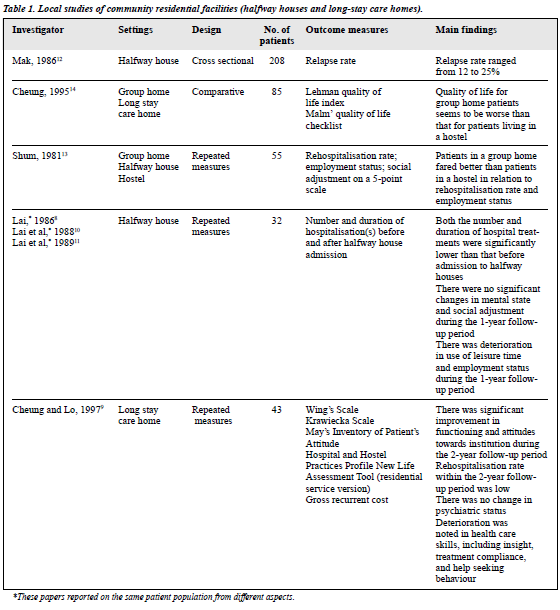

Seven studies have been identif ied8-14 — 5 were con- ducted in the 1980s8,10-13 and 2 in the 1990s9,14 — and reviewed with particular attention to outcome measures. Setting, sample size, outcome measures, background information, and the main f indings of these studies are summarised in Table 1.

The Impact of Community Placement on Patients’ Mental State

An early study demonstrated a positive effect on the mental condition of patients following discharge to the community;3 compared with the period before transfer to HWHs, the number and duration of hospital admissions showed a signif icant reduction.8 However, more recent studies did not conf irm these f indings. Cheung and Lo followed a cohort of 43 patients discharged from CPH to LSCHs and assessed the patients’ mental state by the Krawiecka Scale.9 No signif icant changes could be identif ied following the patients’ discharge to LSCHs. Two further studies failed to f ind any signif icant changes in the psychiatric condition of a group of 27 f irst-time HWH residents at 1-year follow-up.10,11 Assessment of the mental state was based on the global impression of psychiatrists and HWH wardens.

In addition to mental state, the relapse rate to hospital was another common outcome measure used in local studies to indicate the effectiveness of LSCHs and HWHs. Cheung and Lo demonstrated a relatively low rehospitalisation rate among a group of LSCH residents.9 Of the 36 patients staying in an LSCH for the study period, only 4 were readmitted to hospital.

An earlier survey found that the relapse rate for 208 patients admitted to 3 HWHs during a 5-year period (1982 to 1986) was high, ranging from 12 to 25%.12 Such a relatively high relapse rate might be due to poor drug compliance, inadequate supervision of patients, and stressful life events. A comparative study of the relapse rate between group home and HWH/hostel residents found that the patients in the latter facilities had a higher relapse rate than those living in group homes.13 However, it is diff icult to compare the relapse rate between HWH and group home residents due to the differing clinical prof ile of the 2 populations.

To conclude, the majority of local studies found that both LSCHs and HWHs seem to be able to fulf il their objectives to maintain the mental health of residents9-11 and reduce the likelihood of readmission to hospital,9 although contradictory f indings concerning the effectiveness of HWHs to reduce rehospitalisation rates have also been reported.8,12,13

The Impact of Community Placement on Patients’ Social Functioning

With respect to social functioning, it was demonstrated that there was a signif icant improvement in social and community skills among 43 patients discharged from CPH to LSCHs during a 2-year follow-up period.9 These skills were assessed by the Residential Service Version of the New Life Assessment Tool designed by the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association. Behavioural disturbances evaluated by the Wing’s Scale were also noted to have remained stable throughout the 2-year period but there was deterioration in health care skills including insight, treatment compliance, and treatment seeking behaviour.

Contradictory f indings were reported regarding the impact of HWHs on social functioning. Lai et al studied the clinical condition and correlates of social adjustments in a group of 27 f irst-time HWH residents who stayed for 1 year.10,11 There was no improvement in the patients’ social adjustment after 1-year. Moreover, there was a reduction in both the employment rate and use of leisure time. Good social adjustment was associated with young age and short duration of psychiatric illness as well as fewer and less severe symptoms at baseline. Social adjustment was assessed by a 5-point scale consisting of 6 items (self care, use of leisure activities, household duties and budgeting, interpersonal relationships, shopping and use of public facilities, and temper).

A comparison between group home and HWH/hostel residents with respect to psychiatric status and clients’ satisfaction revealed that HWH patients had a lower employment rate than patients living in group homes.13 However, it is difficult to compare the psychiatric state between these 2 groups of patients due to their differing clinical profile.

The above studies indicate that LSCHs may be effective at promoting patients’ social functioning while HWHs are probably less likely to improve the patients’ social adjustment.

Community Resettlement Measured by Multiple Indicators

In addition to traditional outcome indicators (mental state and social functioning), some studies attempted to include other measures such as cost and patients’ subjective perception of psychiatric services and life situations.

In the comparative study by Shum, the cost of treatment and client satisfaction were compared between clients in group homes and those in HWHs/hostels.13 The annual maintenance cost per patient was lower for those in group homes. Unfortunately, the study did not state the mode of assessment and the results of clients’ satisfaction.

Cheung and Lo adopted multiple indicators, including gross recurrent cost, restrictiveness of an institution, and patients’ subjective perception of the institution.9 These investigators showed that the average recurrent cost of LSCHs was half that of CPH. Moreover, the environment in the LSCHs was less restrictive than that of CPH. There was an overall improvement in attitude towards the institution among residents in LSCHs at 2-year follow-up. An intriguing f inding was noted in the answers to Question 13 of May’s Inventory of Patient’s Attitude — Have you any def inite plan?

The percentage of patients who had a future plan (60%) peaked at 6 months after discharge from hospital but dropped back to slightly higher than baseline level (38%) after a longer period of time. The question arises whether this fluctuation reflected disillusionment with community living after an initial period of hope and expectation.

Cheung used 2 multidimensional measures to compare the quality of life of patients in 4 community-based residential settings with different levels of supervision (LSCH, New Life Farm, purpose-built HWH, and group home).14 Overall f indings suggested that patients living in group homes (with no staff supervision) appeared to have poorer quality of life than patients in both LSCHs and HWHs (with staff supervision).

Group home residents had higher ratings in both objective and subjective health indices than patients in LSCHs who experienced more health problems. LSCH patients were rated higher for work, f inance, and daily activity than patients in the group home. In addition to influences attributed to the type of treatment setting, other factors affecting the subjective quality of life of patients included age, sex, diagnosis, age of onset and duration of illness, length of hospital admissions, and income.

Besides maintaining patients’ mental state, both LSCHs and HWHs seemed to be effective at promoting subjective well being (quality of life). However, the group home was less likely to promote residents’ favourable perception of the institution.

Discussion

What preliminary conclusions can be drawn from this review concerning the effectiveness of HWHs and LSCHs to rehabilitate psychiatric patients? Comparing the f indings across studies is diff icult because the trials employed different samples and outcome measures. In addition, all studies had methodological flaws including small sample size, non-validated instruments, and lack of a control group.15 At this point, therefore, the assumption that Chinese psychiatric patients may have a better chance of recovery and quality of life when rehabilitated outside psychiatric hospitals remains uncertain.

Despite their limitations, results of the studies reviewed point in the same direction. Both LSCHs and HWHs were effective at maintaining the mental health of patients.8-11 LSCHs were also effective at improving patients’ social and community skills.9 However, the effectiveness of HWHs to promote social functioning, particularly the use of leisure time, remains unproven.10,11

It is of note that residential services with less staff supervision and restrictiveness (HWHs and group homes) did not always contribute to the improvement in mental state and subjective perception of life situation.12,14 Only 1 study found that patients in group homes fared better than patients living in HWHs and hostels with respect to hospital readmission rate and employment.13 Again, caution is warranted when comparing mental state between HWH and group home residents who have quite different clinical profiles. However, another investigation came to the opposite conclusion, in that patients in group homes had a worse quality of life than patients living in hostels (LSCHs and HWHs).14

Lai et al also demonstrated a reduction in use of leisure time and employment status for patients after admission to HWH.10,11 These studies seem to challenge the prevailing belief that discharging patients to less restrictive residential settings (g roup homes and HWHs) can automatically improve social functioning, mental state, and subjective feelings as well as reduce the rehospitalisation rate.10,11,12,14

Since most of the studies reviewed here did not include hospitalised patients as a control group, it is doubtful whether this assumption can be generalised. Clearly, further studies comparing hospital and community-based settings with respect to patients’ subjective feelings are warranted.

Concerning outcome measures, we found that the assessment tools employed in previous local studies of HWHs and LSCHs were mainly clinically oriented. The measures were used to evaluate mental state, level of functioning, and hospital readmission rate and did not examine the quality of life (QOL) of psychiatric patients. Only one study assessed QOL although, during the past decade, QOL has been widely used as an outcome indicator in western studies examining the effects of deinstitution- alisation.14 Including QOL in the outcome measures to evaluate the effectiveness of psychiatric intervention would add an important dimension to the traditional symptom- focused approach.

Integrating QOL into traditional outcome measures (medication consumption, psychopathology, and admission rates) would give a more comprehensive picture of the effectiveness of local residential services. Many of these services might have limited effects on symptom control, yet may still improve patients’ subjective feelings towards life in general.1,9,16 Patients and their families, who rely on the health system for continuous care, increasingly expect that QOL will be an essential aspect of the management and planning of care.16

The overview of local studies raises several important questions. Will the local community-based residential services (HWHs and LSCHs), like their counterparts in western countries, have a favourable impact on the quality of life of psychiatric patients in comparison with psychiatric hospitals?17,18 Comparative studies conducted by Lehman et al demonstrated that patients living in less restrictive treatment settings tend to have better QOL when compared with hospitalised patients.17,18

An interesting observation about community-based care in western studies was the fluctuation of QOL during the reintegration process. For example, Okin et al have shown that QOL may increase during the f irst 6 months of reintegration and then plateau.19 It is quite possible that this phenomenon also occurs among local psychiatric patients discharged to different community settings, as indicated by the fluctuations in planning for the future observed with local LSCH residents.9 What is the likely cause of this fluctuation? How can patients be assisted to maintain the initial gain in QOL? To answer these questions, further studies should be conducted in Hong Kong to examine QOL of psychiatric patients being cared for in different settings.

Conclusion

In view of the conflicting results of the local studies briefly reviewed here, this paper emphasises the need for further investigation of the effectiveness of HWHs and LSCHs. In the wake of the measured de-institutionalisation that is going to take place in Hong Kong in the coming years, comprehensive assessment of community residential settings should include quality of life.

In addition, long-term hospital patients ought to be included as a control g roup in future evaluations of residential services in Hong Kong to test the widely held assumption that psychiatric patients will have a better chance of recovery and quality of life when rehabilitated outside the hospital.

Furthermore, intensive studies of the effectiveness of HWHs are needed in view of the contradictory f indings reported so far. Quality of life will be a useful outcome measure for future studies of residential settings, to demonstrate a more comprehensive picture of the effectiveness in these services for psychiatric patients in Hong Kong.

References

- Bachrach LL. Lessons from the American experiences in providing community-based services. In: Leff J, editor. Care in the community. Illusion or reality? Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:21-36.

- Mitchell DA, Crosby C, Barry MM. Evaluation of the North Wales resettlement program: methodology and cohort description. In: Crosby C, Barry MM, editors. Community care: evaluation of the provision of mental health services. Aldershot: Avebury; 1995:7-57.

- Braum P, Kochansky G, Shapiro R, et al. Overview: de-institutionalization of psychiatric patients, a critical review of outcome studies. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:736-749.

- Lehman AF, Ward NC, Linn LS. Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. Am J Psychiatry 1982;139:1271-1276.

- Yip KC, Cheung HK, Pang HT. Community psychiatric services. In: Mak KY, Chan CKY, Lo TL, et al, editors. Mental health in Hong Kong, 1996/97. Hong Kong: Mental Health Association of Hong Kong; 1998:77-83.

- Rehabilitation Division, Health and Welfare Bureau. Hong Kong Rehabilitation Program Plan (1998-99 to 2002-03). Hong Kong: Government Secretariat; 1999.

- Choi CW. Psychiatric rehabilitation — the Hong Kong approach. In: Mak KY, Chan CKY, Lo TL, et al, editors. Mental health in Hong Kong, 1996/97. Hong Kong: Mental Health Association of Hong Kong; 1998:13-21.

- Lai B. Hospitalization before and after halfway house admission: an evaluation of effectiveness. HK J Mental Health 1986;5:21-26.

- Cheung HK, Lo KSS. A prospective study on a cohort of Castle Peak Hospital (CPH) patients discharged to the 1st long stay care home (LSCH) of Hong Kong in the initial two years. Paper presented at the 1st International Symposium on Community Psychiatric Rehabilitation; 1997 Jan 13-15; Hong Kong.

- Lai B, Li EWF, So AWK. A follow-up study of social adjustment of halfway house residents. I: Outcome of social adjustment in one year. HK J Mental Health 1988;17:67-73.

- Lai B, Li EWF, So AWK. A follow-up study of social adjustment of halfway house residents. II: Factors affecting outcome in social adjustment. HK J Mental Health 1989;18:11-18.

- Mak KY. Why do residents in psychiatric halfway house relapse? HK J Mental Health 1986;15:72-75.

- Shum PS. Hospital-based community work and aftercare in rehabilitation of chronic schizophrenics. J HK Psychiatr Assoc 1981;1:27-32.

- Cheung HK. Measurement of quality of life (QOL) in patients with persistent serious mental illness in 4 different community settings using 2 different QOL scales. Paper presented at the Regional Meeting of World Psychiatric Association; 1997 Oct 7-10; Beijing, China.

- Mak KY. Psychiatric rehabilitation studies in Hong Kong — a review. In: Mak KY, Chan CKY, Lo TL, et al, editors. Mental health in Hong Kong, 1996/97. Hong Kong: Mental Health Association of Hong Kong; 1998:63-73.

- Sartorius N. Quality of life and mental disorders: a global perspective. In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of life in mental disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:319-328.

- Lehman AF, Possidente S, Hawker F. The quality of life of chronic patients in a state hospital and in community residences. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 1986;37:901-907.

- 18. Lehman AF, Slaughter JG, Myers CP. Quality of life in alternative residential settings. Psychiatr Quart 1991;62:35-49.

- Okin RL, Dolnick JA, Pearsall DT. Patients’ perspectives on community alternatives to hospitalization: a follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 1983;140:1460-1464.