Hong Kong J Psychiatry. 2006;16:57-64

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

K Suhail, HR Chaudhry

Dr Kausar Suhail, Head, Department of Psychology, GC University, Kechehry Road, Lahore, Pakistan.

Dr Haroon Rashid Chaudhry, Head, Department of Psychiatry, Fatima Jinnah Medical College, Lahore, Pakistan.

Address for correspondence: Dr Kausar Suhail, Head, Department of

Psychology, GC University, Kechehry Road, Lahore 54000, Pakistan.

Tel: (92 11) 100 0010; Fax: (92 42) 921 3341;

E-mail: kausarsuhail@hotmail.com

Submitted: July 5 2006; Accepted: November 14 2006

Abstract

Objective: This study was conducted to examine the evolution of symptoms in Pakistani subjects with first-episode schizophrenia from onset until hospital admission by gender and age.

Patients and Methods: Retrospective and current symptoms were assessed in 140 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition schizophrenic patients in Pakistan by using a symptom checklist based on the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition and Structured Clinical Interview for the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale.

Results: The current work failed to show gender differences in age at either the true age of onset or at the time of admission. Negative symptoms showed greater stability with an excess at both times of assessment, whereas positive symptoms showed a higher progression from onset until admission. Significantly greater number of men reported symptoms of avolition, affective flattening, disorganised behaviour, and inappropriate affect, whereas women showed a higher incidence of persecutory delusions. Similarly, early-onset patients were more likely than late-onset patients to exhibit symptoms of affective flattening, inappropriate affect, disorganised behaviour, and delusion of grandiosity. Late-onset patients, on the other hand, exhibited greater ideas of persecution.

Conclusion: The early course of schizophrenia in these Pakistani patients showed reasonable consistency with the findings obtained from other countries. The core symptoms of schizo- phrenia did not show significant differences with gender or age, although in male gender and early-onset disease were associated with greater symptomatology.

Key words: Age of onset, Pakistan, Schizophrenia, Sex factors, Severity of illness index

Introduction

Studies conducted with first-episode schizophrenia have shown a fairly uniform and robust clinical picture. Schizo- phrenia has been reported to begin in early adulthood mainly with negative symptoms, followed by decompensation with positive after a considerable time lag.1 However, there are some inconsistencies concerning the impact of gender and age of onset (AOO) on disease manifestation and symp- toms. The inconsistencies across studies may be related to factors such as differences in diagnostic criteria, method- ologies, chronicity of disease, and age limits of the research sample.

Most previous work about the course of schizophrenia has focused on chronically ill patients with stable symptoms.2-4 However, there is ample supportive evidence that first episode samples are the most representative and allow examination of symptoms close to their genesis.5 Studies involving first- episode cases have typically evaluated subjects at first clinical presentation or first hospital admission,6,7 which in itself is determined by various factors in addition to symptom- atology.8 Early signs and symptoms could start and be detected years before first presentation.1

Gender differences in AOO and symptomatology in schizophrenia have been extensively studied. It is established that the morbid risk for schizophrenia changes with age and that gender has a strong impact on age at onset. Many studies have reported an earlier AOO for men as compared to women.9,10 Incidence rates in men are at their highest in young adulthood, whereas in women a broader peak extending beyond the age of 30 and a second peak between ages 45 and 49 were reported.11 A delay in onset as well as the second peak for the emergence of schizophrenic symptoms in women has been attributed to mildly pro- tective effects of oestrogen.12-14 Indeed, gender differences in AOO have also given rise to hypotheses about genetic differences among men and women in the development of the disorder.15

A number of clinical studies have shown that men display more negative symptoms than women.16,17 In terms of positive symptoms, a greater incidence of auditory hallucinations18,19 and persecutory delusions20 has been reported in women.21 Simi- lar results were found in a community sample consisting of 7076 subjects, when the male gender was associated with a higher prevalence of negative symptoms.

There is disagreement as to whether first-onset schizo- phrenia occurring in late life represents a delayed manifesta- tion of the more common early-onset schizophrenia, or is a distinct syndrome. It has been reported that early-onset patients showed greater specific and non-specific symptoms, especially men,11 and age was inversely correlated with schizophrenic symptoms. Older patients show less prominent hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behaviour and inappropriate affect.17 These findings are consistent with the vulnerability-stress model of schizophrenia,22 which indicates that individuals with a high disposition fall ill earlier in life, whereas those with a lower level of vulnerability present late. It may be reason- able to assume that late-onset schizophrenia will manifest with milder symptoms and less disorganisation.

Although the course and outcome of schizophrenia have been studied across different cultures,10 no systematic work has been conducted in Pakistan. The current work was set up to explore the early presentation and evolution of symp- toms by gender and AOO. To have a best estimate of the AOO and the progression of psychotic symptoms from on- set until presentation, both retrospective and prospective methodologies were employed. The following hypotheses were entertained:

- Negative symptoms would be in excess at the time of onset. 2. Men would have a younger AOO.

- Men would show greater frequency and severity of nega- tive symptoms.

- Men would show a greater frequency and severity of disorganised symptoms of schizophrenia.

- Women would show a higher prevalence of positive symptoms.

- Patients with early-onset schizophrenia could show greater frequency and severity of symptoms.

Patients and Methods

Sample

All patients consecutively admitted from August 2002 to January 2003 in three hospitals in Lahore, Pakistan and re- ceiving the diagnosis of first-episode schizophrenia served as the sample for this study. The diagnosis was made using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).23 In the initial phase of re- cruitment, all patients admitted to these psychiatric units for over 6 months were enrolled for the current study. For inclusion, patients had first admission for the DSM-IV broadly defined schizophrenia (i.e., 295.7, 295.1, 295.2, 295.3, 295.4, 295.9) of at least 4 weeks' duration. A trained Master's level psychologist conducted all the interviews. For each patient, diagnosis was ascertained by subsequent reviews at a formal consensus meeting involving the interviewer and the authors (KS and HRC). The following exclusion criteria were employed: history of intravenous drug use and alcohol misuse; any organic brain syndrome; and severe mental retardation. In total, 234 patients showing psychotic features were screened, of which 140 satisfied the criteria as mentioned above. To measure age effects, the sample was categorised into two age groups according to their age at the time of current admission. Early-onset schizo- phrenia referred to those experiencing psychotic symptoms between ages 16 to 40 years, while those reporting symp- toms at or later than age 41 years constituted the category for late-onset schizophrenia. According to this criterion, 23 patients were categorised as having late-onset schizophrenia.

Demographic and Clinical Data

Information was obtained about demographic and clinical variables such as current age (at admission), marital status, birth order, employment details, personal and family income, previous modes of treatment, family psychiatric history, etc. The age of disease onset was defined as the time when either the patients themselves or their family first noticed any of the core symptoms associated with psychosis. In contrast, age at admission was defined as the time of patients' first admission for a psychotic disorder.

A symptom checklist (SCL) was developed from the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID)24 to assess the evolution of psychotic symptoms from onset until the current admission. The following three main categories of symptoms were assessed: negative, disorganised and positive. Factor analytic studies conducted to examine the relation- ship between positive and negative symptoms have concluded that a third independent disorganisation factor is needed to ascribe the phenomenology of schizophrenia.7,17,25-27 For the purpose of the present study, each of these three dimensions was further subdivided into individual symptom categories fol- lowing the SCID. The positive subscale consisted of primary delusions and hallucinations; the negative subscale consisted of alogia, avolition, and flat affect; and the disorganised subscale consisted of disorganised speech, disorganised behaviour and inappropriate affect. The presence and absence of each symptom was rated on a simple yes/no format.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The frequency and severity of the current symptoms were assessed by interviewing patients with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),28 a 30-item, seven-point rating instrument for assessing positive, negative and other symptoms in schizophrenia. To optimise the scale's objec- tivity and standardisation, a Structured Clinical Interview for the PANSS29 was used. The positive and negative scales consist of seven items each, while the remaining 16 items measure the general psychopathology in the patient. Although positive, negative and general psychopathology scales constitute the three main subscales of the PANSS, the scores of a person can also be categorised into nine subscales: positive, negative, general psychopathology, anergia, thought disturbance, activation, paranoia, depression, and composite. A composite score indicating the relative domi- nance of positive or negative symptomatology is computed by subtracting the negative score from the positive score. A negative value of the composite score indicates a negative profile, while a positive value shows the opposite. In this study, comparisons of age and gender groups were con- ducted on all nine subscales.

Procedure

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients before assessment. Both patients and key relatives were interviewed. Key relative was defined as the relative who had the maximum contact with the patient, and who had been with the patient since the first signs of the current ill- ness were noticed. Wherever possible, additional relatives were also involved in the interview in order to obtain maxi- mum information about the symptoms. During the first week following admission, the patients and the key informants were interviewed by a trained research psychologist, who had achieved satisfactory reliability criteria on the Struc- tured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV and PANSS, both es- tablished on video-recorded interviews. Consensus on diag- nosis and symptom assessment was reached by a conference among the research team, consisting of the authors and the interviewer. The research instruments were applied in the following order: demographic and clinical data sheet, SCL, and the PANSS. To determine the presence and absence of each symptom on the SCL, probing questions were asked following the instructions provided in the training manual of the SCID. The interviewer would enquire retrospectively about past psychotic symptoms, as they first emerged, followed by investigation of the same symptoms in the past 4 weeks. To help obtain more information on the past symptoms, previous hospital medical records were also examined. As this assessment included multiple measures, some interviews were conducted in two or three sessions depending on the convenience of the subjects and families.

In most of the cases, patients and their main family members were interviewed together. AOO was carefully ascertained using personal, cultural and religious events as references. Symptoms at the true AOO and at the first admission were both assessed by the same checklist in order to validate comparisons between them.

Statistical Analysis

In order to determine the association between each symp- tom on the SCL by gender and age groups, chi-squared analyses were computed. Associations between symptoms reported at onset and admission were determined by chi- squared tests. A multivariate analysis was conducted on the quantitative data of the PANSS. The results were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, Version 10 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).Statistical significance was set at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

Gender Differences

Table 1 shows the comparative demographic and clinical variables in men and women. Neither the real AOO or the time of contact differed significantly between men and women. Gender differences were not significant on any of the demographic and clinical variables.

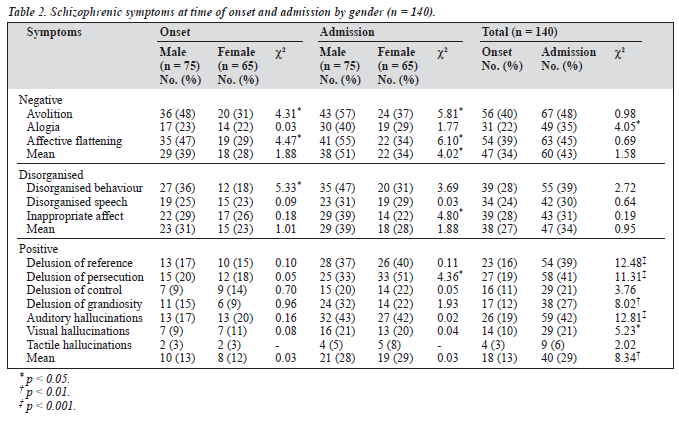

Table 2 shows schizophrenic symptoms at the time of onset and contact by gender and temporal comparison of presenting symptoms. In the negative symptom category, men showed greater frequency of avolition and affective flat- tening both at the times of onset and admission (chi-squared, p < 0.05). For the disorganised dimension, men showed more disorganised behaviour at the time of onset and greater in- appropriate affect at the time of admission. Women had a higher frequency of presenting delusion compared to men at the time of admission (chi-squared, p < 0.05).

All symptoms increased at the time of admission. Posi- tive symptoms (delusions of persecution, reference and grandiosity auditory and visual hallucinations) significantly increased in severity from onset to contact. Of the other two syndrome categories, only alogia increased significantly from onset to contact (Figure 1).

Age of Onset

Differences in three main dimensions of symptoms by AOO are depicted in Table 3. The results showed that patients with early-onset schizophrenia reported more affective flattening, more disorganised speech, and more prevalent delusions of grandiosity, with late-onset patients showing a higher frequency of persecutory ideas. However, the differ- ences were non-significant for mean positive symptoms. Figure 2 shows an interaction between age groups and symptoms at both occasions.

A multivariate analysis was carried out to determine the impact of age (early- and late-onset) and gender on 9 subscales of the PANSS. Multivariate tests showed sig- nificant overall effects of age (F [9, 124] = 3.66, p = 0.0001), and gender, (F [9, 124] = 3.96, p = 0 .0001), along with significant interactions (F [9, 124] = 2.58, p = 0.01) on the ratings of the PANSS. However, effect sizes for gender, age and their interactions were small (0.34, 0.31, and 0.29 respectively) [Table 4]. The analysis of significant interaction between age and gender indicated that the early-onset men showed greater severity of negative and paranoid symptoms, whereas the late-onset women scored higher on both.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic attempt to investigate the early manifestations of schizo- phrenic symptoms in Pakistan by gender and age. The major strengths of this work were that it examined symptoms in new cases covering the whole age range, thus avoiding the distortions that might result from different stages of illness, or from age-related environmental factors after a lengthy course of illness. Moreover, the study evaluated the differ- ent symptom profiles from onset until first admission using the same measures. Inclusion of all consecutively admitted patients during a specific time period further strengthened the design by reducing the possibility of selection biases.

Gender differences in schizophrenia are among the few robust and well-replicated findings.30 Contrary to previous results, the current work failed to reveal gender differences in age either at the true AOO or at the time of admission. Generally, studies have reported an earlier age of admis- sion for men as compared to women.1,31-34 The current study, however, did not find such differences at AOO. Men, never- theless, had greater time lag between onset and admis- sion compared to women. The similar ages at onset and at admission for men and women may be related to socio- cultural factors in Pakistan. Parents are generally more con- cerned about the marriage prospects of their daughters than their sons; hence, it may be speculated that they have a com- paratively lower threshold in detecting any abnormality in their daughters' behaviour, and this might have affected both early detection of onset and contact within the psychiatric service. A few studies also failed to observe gender differ- ences in AOO. Folnegovic and Folnegovic-Smalc35 did not find significant differences in average AOO or age at first admission in a sample of 356 men and 323 women. Jablensky and Cole analysed data of 778 men and 653 women patients obtained from 3 developing and 7 developed countries.30 By applying a generalised linear modelling strategy, they found that failure to control for marital status and premorbid personality may explain a large part of the difference reported previously. They concluded that the gender differ- ence in the age at onset of schizophrenia was not a robust biological characteristic of the disorder.

The majority of all admissions (70%) occurred at or before age 25 for both genders, indicating that the morbid risks for schizophrenia change with age. Similarly, the onset of symp- toms occurred much earlier than the actual admissions.1,8 According to the information obtained from the patients and their key family members, schizophrenic symptoms first appeared on average about 15.49 months before the first admission, with a maximum of 96 months (8 years). Hafner et al reported a greater time lag of about 4.5 years before first hospital admission, with a maximum of 31.5 years.8 These differences can be attributed to the use of different method- ologies and research questions; the current study targeted the first appearance of psychotic symptoms, whereas Hafner at al recorded the first signs of psychological disturbance.

Men outnumbered women in the frequency of both nega- tive and disorganisation symptoms categories. Greater fre- quency of avolition and affective flattening in men both at the time of onset and admission may suggest a greater deterior- ation in functioning. Men also showed a higher frequency of disorganised behaviour (in both occasions) and inappropriate affect (only at the time of admission) than their female counter- parts. The scores on PANSS also suggested that men showed greater severity of negative symptoms and thought disturbance. The excess of negative symptoms in men as compared to women has been reported in clinical populations,18,22 relatives of male probands,36 and also in the general population.5

In contrast to negative and disorganisation symptoms, posi- tive symptoms profiles appeared relatively comparable in men and women. The excess of persecutory delusions in women has been described earlier.20 The increased propensity of male patients to develop ideas of grandiosity replicated the find- ings of earlier studies from Pakistan,37 India,38 Germany39 and China.40 The Pakistani study was conducted with 48 men and 50 women diagnosed with schizophrenia using Present State Examination categories.41 The researchers indicated the preponderance of grandiose themes reflected the social and cultural roles in society, especially traditional one. The content of religious delusions in Pakistani men reflected grandiosity themes, a finding also reported in Kenyan men.42

Comparisons between early- and late-onset patients sug- gested a higher frequency of negative and disorganisation categories. The early-onset patients also reported more grandiosity, while the late onset showed more persecutory ideas. Previous studies have frequently reported the excess of negative43 and disorganisation symptoms11,44 in early-on- set schizophrenia. Differences between age groups in the experience of delusions were congruent with the earlier work. A greater frequency of delusion of grandiosity in early- onset patients45 and a high frequency of persecutory ideas in late-onset schizophrenia has been reported previously.1,9,11,46 It is still unclear as to why different forms of delusions would be prevalent in different age groups. It may be that ideas of grandiosity are more likely to arise when patients are younger and thus display greater strength and vitality, where- as fear of losing these as well as professional competition and jealousy predispose older people to ideas of mistrust.

The vulnerability-stress model of schizophrenia concep- tualises the possible underlying mechanisms to account for changes with age by postulating that individuals with a high vulnerability fall ill earlier in life, whereas those having a lower level of this susceptibility fall ill later.22 If a high dis- position is correlated with greater severity in symptoms, it is reasonable to assume that a milder form of symptomatology will be associated with the increasing age. Hafner et al explained the age effect on the symptomatology of schizophrenia by sug- gesting that the greater stability of a fully developed personal- ity might offer some defence against mental disorganisation.11

Schizophrenia research provides extensive support for a greater deterioration and dysfunction in early-onset patients. Brodaty et al found clinical similarities in 27 late-onset and 30 early-onset patients, but the early-onset subjects had more negative symptoms, formal thought disorder, delusions of control and guilt, and had significantly poorer instrumental activities of daily living.43 Similar results have been reported from an earlier study with 470 patients with non-affective non-organic psychosis.45 All psychiatric symptoms associ- ated with schizophrenia were more common in the early- onset patients. We found a few significant differences in symptoms shown in the two age groups. One possible reason for this could be that there were a few (n = 23) late-onset patients (³ 40 years) and all of them were under age 61, while the heterogeneity of schizophrenic disorders has been expected more with onset after the age of 60.47 Moreover, these studies had imposed a higher minimum age limit for definition of the late-onset group than the current study.43,45

Gender and age had significant impacts on the progres- sion of symptoms. Male patients and early-onset disease showed predominantly negative and disorganisation symp- toms. In women and late-onset patients, although the disease started with a predominance of negative symptoms, positive symptoms were in excess at the time of admission.The symp- toms of schizophrenia also appeared to be influenced by the joint interplay of gender and age, with the early-onset men and the late-onset women both showing greater severity of negative and paranoid symptoms on the PANSS.

Despite these differences, core symptoms of schizophre- nia did not show essential differences by age and gender groups. As far as progression of symptoms is concerned, this illness started with negative symptoms with a progres- sion to negative, disorganised and positive symptoms until the time of admission. Hafner et al concluded that in 70% of cases schizophrenia began with only negative symptoms, and only in 10% of cases positive symptoms clearly occurred first.1 The present results were consistent with the previous reports as 51% of the total sample reported only negative symptoms at the time of onset. The time of admission, however, was associated with increase in all categories of symptoms. An earlier study following patients prospectively for 3 years showed that negative symptom exacerbations were significantly concurrent with increases in positive symptoms.48 Negative symptoms associated with delusions and hallucinations are believed to reflect compensatory strategies that serve as a form of protection against the putative threat. Patients suffering from paranoia engage in inter-personal avoidance and other active safety behaviour.49 Decisions to contact the psychiatric services seem to be largely determined by the onset and increase in positive symptoms, which have been found to be related to sub- sequent hospitalisation.50 It is reasonable to assume that positive symptoms with persecutory, grandiose or bizarre ideas as well as hallucinations may appear more alarming to the family than withdrawn behaviour of the patient. Conversely, nonspecific factors associated with the admis- sion process as well as stigma attached to hospitalisation for mental illness may also be partly responsible for an increase in certain delusional ideation. Drake et al5 explained that the higher prevalence of persecutory delusions at the time of admission might be related to the process of first admission triggering overt suspicion and hostility.

The findings of this work need to be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, conclusions in relation to age effect were made on the basis of cross-sectional data. Although longitudinal follow-up can lend the greatest amount of information about the course of schizophrenia, such methods suffer from substantial inherent limitations, such as a sampling bias toward patients who are accessible over time in institutions. Moreover, chronicity of the illness and treatment creates obstacles in delineating the effects of long-term antipsychotic exposure.17 Second, the validity and reliability of earlier psychotic symptoms could be questioned, as this information relied largely on the reflection of patients and relatives. However, retrospective evaluation is the only practical way to collect data on the preclinical course of schizophrenia.8 Several measures were adopted to reduce these biases: patients' medical past records were examined,and well- defined personal and cultural events were used as anchor points to ensure the accuracy of temporal order and dating.

Conclusions

This study showed qualitative similarities and differences in the core symptoms of schizophrenia across gender and age groups. Being male and having an early-onset of dis- ease appeared to be associated with greater symptomatology, especially negative and disorganisation syndromes. Men and women did not differ significantly in age at the time of either onset or admission. The early symptomatology in Pakistani first-episode patients with schizophrenia is reasonably consistent with the findings from other countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Government College University Lahore and Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals, Pakistan for provid- ing funds for this research.

References

- Hafner H, Maurer W, Loffler W, et al. The epidemiology of early schizophrenia: Influence of age and gender on onset and early course. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164:29-38.

- Liddle PF. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: A re-examination of the positive-negative dichotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:125-51.

- Lindenmayer JP, Grochowski S, Hyman RB. Five factor model of schizophrenia: replication across samples. Schizophr Res. 1995;14:229-34.

- Nakaya M, Suwa H, Ohmori K. Latent structures underlying schizophrenic symptoms: A five-dimensional model. Schizophr Res. 1999;9:3-50. 5.

- Drake RJ, Dunn G, Tarrier N, Haddock G, Haley C, Lewis S. The evolution of symptoms in the early course of non-affective psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:171-9.

- Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group. The Scottish first-episode schizophrenia study VIII. Five year follow-up: Clinical and psychoso- cial findings. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:496-500.

- Vazquez-Barquero JL, Lastra I, Nunez JC, Castanedo SH, Dunn G. Patterns of positive and negative symptoms in first episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:693-701.

- Hafner H, Riecher-Roossler A, Hambrecht M, et al. IRAOS: An instru- ment for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:209-23.

- Hafner H, Maurer W, Loffler W, Riecher-Rossler A. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:80-6.

- Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. Schizophrenia: Manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures: A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1992;20:1-97.

- Hafner H, Hambrecht M, Loffler W, Munk-Jorgensen P, Riecher- Rossler A. Is schizophrenia a disorder of all ages? A comparison of first episode and early course across the life-cycle. Psychol Med. 1998; 28:351-65.

- Hafner H, Behrens S, de Vry J, Gattaz WF. Oestradiol enhances the vulnerability threshold for schizophrenia in women by an early effect on dopaminergic neurotransmission. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991:241;65-8.

- Riecher-Rossler A, Hafner H, Dutsch-Strobel A, Oster M, Stummbaum M, van Gulick-Bailer M, et al. Further evidence for a specific role of estradiol in schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry. 1994;36:492-5.

- Seemen MV, Lang M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:185-94.

- DeLisi LE. The significance of age of onset for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:209-15.

- Roy MA, Maziade M, Labbe A, Marette C. Male gender is associated with deficit schizophrenia: A meta analysis. Schizophr Res. 2001;47:141-7.

- Schultz SK, Miller DD, Oliver SE, Arndt S, Flaum M, Andreasen NC. The life course of schizophrenia: age and symptom dimensions. Schizophr Res. 1997;23:15-23.

- Rector NA, Seeman MV. Auditory hallucinations in women and men. Schizophr Res. 1992;7:233-6.

- Sharma RP, Dowd SM, Janicak PG. Hallucinations in the acute schizo- phrenic type psychosis: Effects of gender and age of illness onset. Schizophr Res. 1999;37:91-5.

- Goldstein JM, Santangelo SL, Simpson JC, Tsuang MT. The role of gender in identifying subtypes of schizophrenia: A latent class analytic approach. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16:263-75.

- Maric N, Krabbendam L, Vollebergh W, Graaf RD, Os JV. Sex differ- ences in symptoms of psychosis in a non-selected general population sample. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:89-95.

- Zubin J, Spring B. Vulnerability- a new view of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1977;86:103-26.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Washington DC. American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Miriam Gibbon MSW, Williams DSW, Janet BW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Pa- tient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

- Andearsen NC, Arndt S, Alliger R, Miller D, Flaum M. Symptoms of schizophrenia: Methods, meanings, and mechanisms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:341-52.

- Thompson PA, Meltzer HY. Positive, negative, and disorganization factors from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia and the Present State Examination: A three-factor solution. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:344-51.

- Pfohl B, Winokur G. The evolution of symptoms in institutionalized he- bephrenic/catatonic schizophrenics. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;141:567-72.

- Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261-76.

- Opler LA, Kay SR, Lindenmayer J. Structured Clinical Interview for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. New-York: Multihealth Systems Inc.; 1999.

- Jablensky A, Cole SW. Is the earlier age at onset of schizophrenia in males a confounding finding? Results from a cross-cultural investigation. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:234-40.

- Kraepelin E. Dementia praecox and paraphrenia. (RM Barclay, Transl.) New York Robert E. Krieger; 1919.

- Angermeyer MC, Kuhn L. Gender differences in age at onset of schizo- phrenia: An overview. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1998;237:351-64.

- Eaton WW. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Epidemiol Rev. 1985;7:105-26.

- Loranger AW. Sex differences in age at onset of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:157-61.

- Folnegovic Z, Folnegovic-Smalc V. Schizophrenia in Croatia: Age of onset differences between males and females. Schizophr Res. 1994; 14:83-91.

- Goldstein JM, Faraone, SV, Chen WJ, Tsuang MT. Genetic heteroge- neity may in part explain sex differences in the familial risk for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38:808-13.

- Suhail K. Content of delusions in Pakistani schizophrenic patients by gender and social class. Psychopathology. 2003;36:195-9.

- Kala AK, Wig NN. Delusions across cultures. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1982;28:185-93.

- Tateyama M, Asai M, Kamisada M, Hashmoto M, Bartels M, Heimann Comparison of schizophrenic delusions between Japan and Germany. Psychopathology. 1993;26:151-8.

- Rin H, Wu K, Lin C. A study of the content of delusions and hallucina- tions manifested by the Chinese paranoid psychotics. J Formos Med Assoc. 1962;61:46-57.

- Wing JK, Cooper JE, Sartorius N. Measurement and classification of psychiatric symptoms: An instruction manual for the PSE and Catego program. London: Cambridge University Press; 1974.

- Ndetei DM, Singh A. Study of delusions in Kenyan schizophrenic pa- tients diagnosed using a set of research diagnostic criteria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;66:208-15.

- Brodaty H, Sachdev P, Rose N, Rylands K, Prenter L. Schizophrenia with onset after age 50 years: Phenomenology and risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:410-5.

- Remschmidt HE, Schulz E, Martin M, Warnke A, Trott GE. Child- hood-onset schizophrenia: History of the concept and recent studies. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:727-45.

- Howard R, Castle D, Wessely S, Murry R. A comparative study of 470 cases of early-onset and late-onset schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1993; 163:352-7.

- Yassa R, Suranyi-Cadotte B. Clinical characteristics of late-onset schizo- phrenia and delusional disorder. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19:701-7.

- Post F. Persistent persecutory state of the elderly. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1966.

- Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Horan WP, Subotnik KL, Mintz J. The timing of negative symptom exacerbations in relationship to positive symptom exacerbations in the early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:333-42.

- Rector NA, Beck AT, Stolar N. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia: A cognitive perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50:247-57.

- Schuldberg D, Quinlan DM, Glazer W. Positive and negative symptoms and adjustment in severely mentally ill outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 1999;85:177-88.