East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2016;26:129-36

THEME PAPER

Ms Esther Fung, MSocSc (Clin Psy), Clinical Psychologist, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Tak-Lam Lo, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsy, Hospital Chief Executive, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Dr Raymond WS Chan, PhD, Consultant, New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Mr Francis CC Woo, RN (Psy) (HK), RN (UK), MHSM (Aus), Senior Nurse Officer,nKwainChungnHospital,nHongnKongnSAR,nChina.

Ms Clara WL Ma, BSc (Hons), Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China. Mr Bill SM Mak, BA (Hons), Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, China.

Address for correspondence: Ms Esther Fung, 1/F, Block J, Kwai Chung

Hospital, Kwai Chung, New Territories, Hong Kong SAR, China. Email: estherfung@ha.org.hk

Submitted: 8 October 2015; Accepted: 1 February 2016

Abstract

A lack of knowledge about mental health and stigma of the mentally ill are barriers to the treatment of mental disorders. To reduce these barriers, anti-stigma campaigns using a knowledge contact approach were launched to raise public mental health knowledge by education and to reduce stigma by encouraging contact with individuals with mental disorders. The current study attempted to investigate the outcome of a knowledge contact–based programme in adolescents and adults in the Hong Kong Chinese population. Matched background individuals served as controls. Results from the 149 adolescents and 98 adults who participated in our programme showed that they had superior mental health literacy to the control group. Although both adolescents and adults showed a positive outcome on most measures of stigma, the former showed positive outcome on more measures of stigma than the latter. Our results support the initiative of using a knowledge contact–based anti-stigma campaign in Chinese societies. The results of this study provide preliminary data that will help inform and guide future research and development of effective mental health awareness programmes specific to people of various age-groups in the Chinese community.

Key words: Adolescent; Adult; Hong Kong; Knowledge; Mental disorders; Social stigma

Introduction

Barriers to Treatment of Mental Disorders

One of the barriers to treatment of mental disorders is low mental health literacy, that is, the poor ability to recognise specific mental disorders, the lack of knowledge about causes and interventions, and attitudes that hinder appropriate help-seeking behaviour.1 Low mental health literacy makes early recognition of and appropriate intervention in mental disorders difficult.2,3

Another barrier to treatment of mental disorders is public stigma — the reaction of the general public to people with mental illness. When people agree to the stereotype that individuals with mental illness are dangerous, incompetent and dependent, unpredictable, flawed in character, at fault for their illness, and / or unlikely to recover,4,5 they become prejudiced. This leads to negative emotional reactions (e.g. fear, anger) and discriminatory behaviour, such as avoidance and withholding help or opportunities.4

As a result of public stigma, people with mental illness are denied rightful opportunities related to work and other important life goals,6 undermining their quality of life.4

Moreover, when public-held stereotypical beliefs are also endorsed by the individuals with mental illness, self-stigma ensues and leads to other problems such as avoidance and non-adherence to treatment, thereby limiting the prospect of recovery.7,8

Levels of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma in the General Public in Hong Kong

There is still room for improvement in the level of mental health literacy of the general public of Hong Kong. Some individuals wrongly attribute the cause of mental illness to supernatural powers, such as punishment for sins by ancestors or imbalance of ‘Yin-Yang forces’.9 Even after 10 years, a study by Siu et al10 found that about 10% of those surveyed wrongly attributed the cause of psychosis to disturbance by supernatural forces, about 20% wrongly believed that depressive symptoms were not indicative of psychiatric disorder but a ‘normal’ reaction to setbacks, and 7% thought that seeking professional help would increase suicide risk. Further, the youngest respondents (15-19 years) achieved the lowest knowledge score.10

In 2011, a survey in Hong Kong by the Equal Opportunities Commission found that people with mental illness were consistently among the most stigmatised and avoided groups in various areas of life, including housing, public services, and education.11 More than half of those surveyed said they did not want people with mental illness to live in their neighbourhood, while nearly 70% disagreed that integrative schooling is preferable for children with mental illness.11 There continues to be local opposition to the setting up of integrated community centres for mental wellness in various districts.11 We still have a long way to go to reduce the stigma associated with mental health.11

Knowledge Contact Approach as a Way to Reduce Barriers to Treatment

A method suggested by the World Health Organization3 to remove barriers to mental health treatment was to launch public awareness and education campaigns based on the knowledge contact approach.12

Educating the public about mental illnesses, especially dispelling myths about mental illness and replacing them with facts, can help to improve mental health literacy,4,12 and even improve attitudes towards people with mental illness.4

Education programmes have been found to be effective for children,13 adolescents, and adults.4 Education that targets young minds is especially important; research has found that negative attitudes towards mental illness expressed by adults have their roots in early childhood.5,14

As well as increasing knowledge, facilitating contact between participants and people with mental illness can further reduce stigmatising attitudes.15,16 The optimal conditions for contact include: an equal status of the participants, common goals, no competition, institutional support for contact (i.e. the contact is sponsored or endorsed by management of an organisation), and frequent contact with individuals who mildly refute the stereotype.16,17

Pettigrew18 theorised that contact reduces stigma via the following processes: (a) learning about the outgroup; (b) changing behaviour (social distancing); (c) generating affective ties through emotion, especially reducing anxiety and increasing empathy; and (d) in group reappraisal.

Western studies of anti-stigma programmes utilising a knowledge contact approach found that these programmes were effective in improving students’ short-term recall of mental health knowledge12-14 and their attitude towards people with mental illness for up to 6 months.13 Locally, a recent study suggested that a programme that provided education and video-based contact for students aged 13 to 18 years was effective in enhancing their knowledge and reducing their stigma in the short term.19 Nonetheless, local data on how such programmes impact on the level of stigma in adults are scarce.

Objectives of the Present Study

The present study examined the outcome of a knowledge contact–based anti-stigma programme for adolescents and adults in the Hong Kong Chinese population. The programme was jointly organised by Kwai Chung Hospital and Mindset, a volunteer group of the corporate Jardine Matheson Group that intends to make a positive difference in the field of mental health. It was launched in 2002 following recommendations made in the World Health Report 20013 that called for the launch of more public education and awareness campaigns worldwide to reduce barriers to mental health treatment such as low mental health literacy and stigma. Content of the programme was designed and delivered by professionals from Kwai Chung Hospital, including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and a psychiatric nurse. Each programme spanned 1 to 2 years, with the objectives of: (1) increasing mental health literacy in adolescent participants through education, and (2) reducing stigmatisation of mental illness by participants through contact with people with mental illness.

Schools that were interested in joining the programme recruited Form 4 students as participants. Adults were recruited from the Jardine Matheson Group. The adult volunteers received the same amount of education and contact as the students, but with additional 6 hours of basic training to help facilitate the planning and / or implementation of the educational and contact activities with students.

It was expected that both adolescents and adults who participated in the programme would show a similar increment in mental health knowledge and reduction in stigmatising attitudes and social distance.

Methods

Design, Sampling, and Procedures

This study was carried out in 2012 and was observational in nature with a convenient control sample. The study involved the following groups: (1) student and (2) adult experimental groups who had participated in and graduated from the programme between 2002 and 2012, as well as (3) student and (4) adult control groups who did not participate in the programme but were matched for gender, age, and education level.

Phone calls were made to past student and adult participants to explain the background of the study and encourage their participation. If participants gave verbal consent, a pack containing a consent form and the set of self- report questionnaires used in the study (Chinese version) was sent to them. Participants mailed completed questionnaires to a designated address. The control sample was derived from the general public in 2012 through convenient sampling. Those who completed the questionnaires were given an incentive consisting of a chance to win a mobile phone.

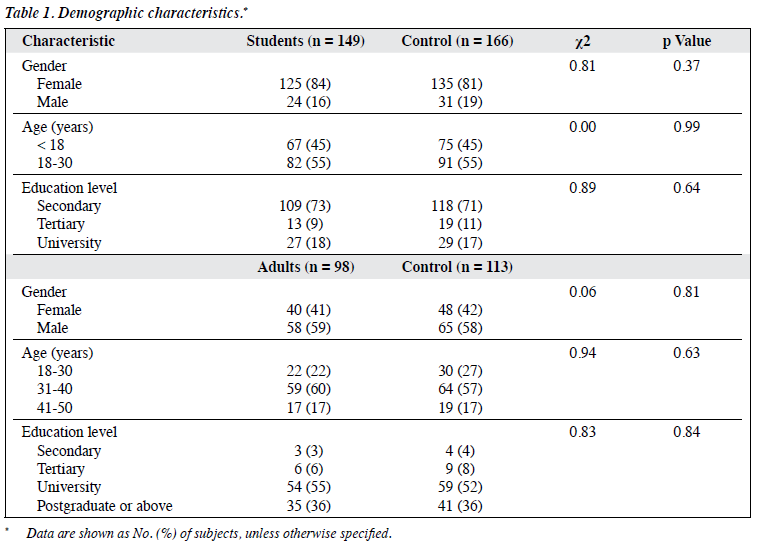

A total of 149 valid questionnaires were collected from student subjects, 98 from adult subjects, 166 from student controls, and 113 from adult controls. Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests found no significant differences in gender, age, or education level between subject and control groups in both students and adults (Table 1).

Intervention

The programme included the following components intended to enhance mental health literacy and reduce stigma perceived by participants.

Participants attended a total of 5 interactive educational workshops facilitated by adult volunteers during the course of the programme, each lasting for approximately 3.5 hours, and covering various topics related to mental illness. Some modifications were made to the workshop content over the past 10 years due to a need to improve programme delivery based on participants’ feedback. Nonetheless, the core components in promoting mental health literacy remained unchanged: stigma reduction education, dispelling myths and giving facts related to mental illness, introducing the biopsychosocial causes of various mental illness, and providing information about common mental disorders faced by adolescents (e.g. anxiety, depression).

The programme also provided a platform for participants to have direct contact with individuals who were recovering from a mental illness. This served as the aforementioned optimal conditions for contact to reduce stigma.16,17 Participants had to organise and / or participate in 6 volunteer services in which they engaged in half- day to full-day structured activities with the persons-in- recovery over the course of the programme. There were slight variations in the format of activities run by different adolescent participants from different schools, but each school had to submit plans that were endorsed by the programme clinical psychologist prior to each activity, to ensure that the activity fulfilled the optimal conditions for contact.

With the guidance of adult volunteers, student participants also organised at least 4 mental health promotional activities in their own school, to help enhance mental health literacy of other students (non-participants) and promote the anti-stigma message to their school community.

Assessing Mental Health Literacy

Mental health literacy was assessed based on the ability to perceive problems as mental illness and identify specific disorders, as well as the knowledge of mental illness including facts, causes, and treatment.

Ability to Identify Mental Illnesses

Using open-ended questions, respondents were asked to indicate how they would label the problems described in 2 vignettes that depicted the symptoms of 2 persons with different mental problems, namely depression and schizophrenia. The 2 vignettes were developed by Jorm et al,1 and were translated into Chinese by a professional translation company.20 These 2 disorders were chosen as the focus of studies because they have been, and still are, the main target of interventions aimed at reducing the stigma of mental illness.21

Mental Health Knowledge

Respondents were invited to complete a self-developed 12-item true-false Knowledge Measure that would identify elements of mental health literacy important in helping individuals to identify and manage mental illness and reduce stigma.2 Scores ranged from 0 to 12, with a higher score indicating more mental health–related knowledge.

Assessing Stigma

The level of stigmatisation was assessed by personal attributes,21 emotional reactions,21 social distance,22 and attitude.23

Personal Attributes

The Perceived Dependency and Perceived Dangerousness Scale was developed by Angermeyer and Matschinger21 to measure the 2 most common stigmatising attributes of people suffering from mental illness, dangerousness, and dependency. Respondents were asked to rate the level of their perceived dangerousness (unpredictable, lack of self- control, aggressive, frightening, dangerous) and perceived dependency (needy, dependent upon others, helpless) of the individuals depicted in the depression and schizophrenia vignettes using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 for each of these 8 items. Higher mean scores on each of these 2 subscales indicated higher level of perceived dangerousness and dependency, respectively. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was good for perceived dangerousness (0.88) and acceptable for perceived dependency (0.60).

Emotional Reactions

The Emotional Response Scale developed by Angermeyer and Matschinger21 was used to measure common emotional reactions towards people with mental illness. Respondents rated their level of fear (uneasiness, fear, feelings of insecurity), pity (sympathy, empathy, desire to help), and anger (anger, ridicule, irritation) towards the individuals depicted in the depression and schizophrenia vignettes, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 for each of these 9 items. Higher mean scores on each of these 3 subscales indicated higher level of respective emotion. Internal consistency of these 3 subscales was good (Cronbach’s alpha: fear 0.79, pity 0.74, and anger 0.77).

Social Distance

The Social Distance Scale was developed to measure respondents’ desire for social distance from individuals with mental illnesses.22 The Scale comprises 7 items that respondents were invited to rate their level of social distance on a 4-point Likert scale towards the individuals depicted in the depression and schizophrenia vignettes. The mean score was calculated for these 7 items. A higher mean score indicated more willingness to interact with the individual with mental illness (i.e. lower social distance). The Social Distance Scale has previously been used in local studies, with good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.83-0.94).20

Attitude

The Community Attitudes towards the Mentally Ill scale comprises 22 items developed by Taylor et al24 to measure respondents’ attitude towards mental illness and people with psychiatric disorders. It was translated into Chinese by Song et al,23 and validated in the Taiwanese Chinese population. The composite score was the mean score of all items in the scale. A higher score indicates a more stigmatising attitude towards people with mental illness. The scale has satisfactory reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha from 0.78 to 0.85.23

Verbal and written informed consent were obtained from all participants. Ethics approval for this study was granted by Health in Mind Committee of Kwai Chung Hospital.

Results

Impact on Mental Health Literacy

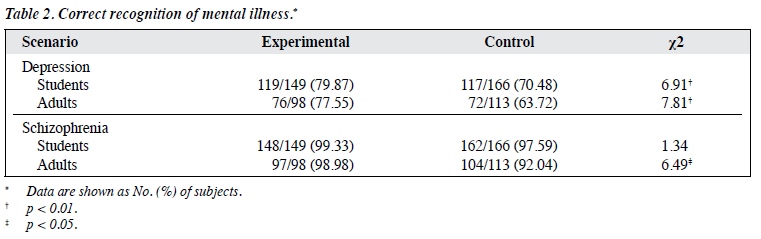

Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests showed that for the depression vignette, a significantly higher percentage of participants (both students and adults) was able to identify the problem as a mental illness compared with controls. Interestingly for the schizophrenia vignette, there were no significant differences between the proportion of participant students and control students who were able to identify the problem correctly, while significantly more adults than controls were able to identify the problem as mental illness (Table 2).

On the 12-item Knowledge Measure, both student and adult participants scored significantly higher than their control group (mean ± standard deviation; students: 10.76

± 1.03 vs. 9.50 ± 1.74; t(272.50) = 7.89, p < 0.01; adults: 10.89 ± 1.09 vs. 10.05 ± 1.41, t(209) = 4.75, p < 0.01).

Impact on the Level of Stigma

Personal Attributes

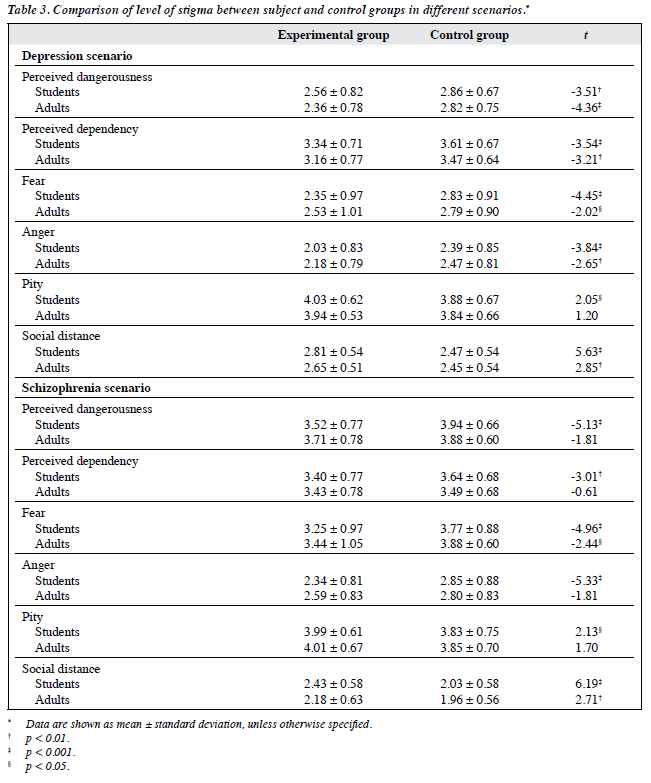

For the vignette of depression, both student and adult participants expressed significantly lower levels of perceived dangerousness and dependency compared with their control counterparts (Table 3).

For the scenario depicting schizophrenia, student participants expressed significantly lower level of perceived dangerousness and dependency than the controls. Nonetheless, no such significant difference was noted between adults and their controls (Table 3).

Emotional Reactions

For the depression scenario, both student and adult participants showed significantly lower levels of fear and anger compared with controls. Interestingly only student participants, not adults, had a significantly higher level of pity (Table 3).

For the schizophrenia scenario, both student and adult participants had a significantly lower level of fear than their controls. Yet only student participants, not adults, expressed a significantly lower level of anger and higher level of pity than their respective control groups (Table 3).

Social Distance

For both depression and schizophrenia vignettes, both student and adult participants had a significantly higher mean social distance score (i.e. more willingness to interact with people with mental health problems) than that of controls (Table 3).

Attitude

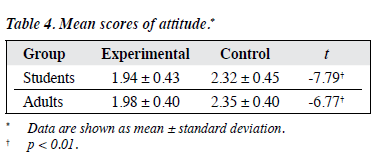

Both student and adult participants had a significantly lower mean stigmatising attitude score when compared with their control group (Table 4).

Discussion

Overall, both student and adult participants had a higher level of mental health literacy and lower level of stigma towards individuals with mental illness, compared with those who did not participate in the programme. There were nonetheless slight variations in the level of differences for various constructs among various participant groups.

Mental Health Literacy

Both student and adult participants had a significantly higher level of mental health knowledge than controls, including beliefs about risk factors and causes of mental illness, myths and facts of mental illnesses, self-help interventions, available professional help, and attitudes that facilitate appropriate help-seeking.

Also, participants’ ability to identify mental illness was generally significantly higher than controls, with more adult participants able to identify both depression and schizophrenia vignettes, and more student participants able to identify depression compared with controls.

Interestingly, there was no significant difference between the very high proportion of student participants and controls who correctly identified schizophrenia. This could be due to insensitivity of the schizophrenia vignette in differentiating people with and without knowledge of schizophrenia, which is a limitation of our study, or due to the effectiveness of a territory-wide campaign since 2001 about early psychosis that targeted young adolescents.25

Raised awareness of this mental disorder in the general public could result in the high proportion of correct answers in the control group. Nonetheless, this requires further validation as we have no baseline data from either experimental or control group for comparison.

Level of Stigma

Student participants endorsed a less negative perception (perceived dangerousness and perceived dependency) and emotions (fear and anger) and more pity towards individuals with depression and schizophrenia than their counterparts in the control group. Student participants also had a less stigmatising attitude to people with these mental disorders, and were more willing than controls to interact with such individuals.

Compared with controls, adult participants tended to endorse significantly less negative perceived personal attributes (including both perceived dangerousness and perceived dependency) towards individuals with depression only, not to individuals with schizophrenia. In terms of emotional reactions, adult participants showed significantly less fear of both types of mental illness, but less anger only to individuals with depression, not schizophrenia, compared with their controls. Adult participants also showed less stigmatising attitude towards, and were also more willing to interact with, individuals with depression and schizophrenia than the controls. Their level of pity towards people with depression and schizophrenia was not significantly different to that of the controls.

The lack of a significant difference between the adult participants and their controls with regard to perceived dangerousness, perceived dependency, and anger towards people with schizophrenia, and level of pity towards people with depression and schizophrenia, could indicate that the adult participants continued to endorse negative stereotypes towards people with schizophrenia given our current level or components of intervention.

One of the reasons that could account for such a lack in difference is that attitudes are formed at a young age, and reinforced by other people in the environment / mass media as people grow older, thus attitudes adopted may become more resistant to change in adulthood.26 Another reason for this lack of difference in stigma among adults is that our current level of education and contact is not the most effective for adults: recent studies found that although both education and contact positively reduced stigma towards mental illness for both adults and adolescents, education was more effective for adolescents and contact was more effective for adults.27 Our results could mean that the current components of our programme more effectively reduce the stigma perceived by adolescents than by adults. In order for adults to achieve the same level of change as students, a higher level of intervention or varying the ratio of components of intervention might be needed. Nonetheless, the aforementioned speculations about differential effects of the intervention on various age-groups require further exploration and more baseline data to validate.

Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Directions

Our results reveal that both our adult and adolescent programme participants had greater mental health knowledge and a less stigmatising attitude towards individuals with mental disorders than the controls, and the difference is probably greater in adolescents than in adults. It appears that our programme can improve participants’ (adolescents in particular) mental health knowledge and reduce stigmatisation in the local Chinese population, although conclusive results cannot be drawn at this stage. More vigorous research with baseline data collected and varying components of intervention are needed to confirm such a hypothesis.

The current study had some limitations. First, the programme was evaluated using self-report measures. Self-report measures of attitude and stereotypes are rather susceptible to socially desirable responses, and may not reliably predict discriminatory behaviour.28 Second, participants of the experimental group were volunteers. This may have introduced selection bias since those with more interest and more dedication to the programme may have had a more open attitude and show greater improvement from the programme.29 Third, there were other confounding variables that were not controlled for but could have affected the outcome, such as contact with people with mental illness outside of the programme.30 There was also difficulty in performing a one-to-one matching due to practical constraints that undermined the suitability of our control group for comparison. Finally, the current lack of baseline data for comparison of changes in various age- groups made it difficult to draw conclusions about causal relationships.

Above all, the current study provides valuable local data for both adolescents and adults regarding the outcome of such campaigns. The results generated from this study can help inform and guide the future development of effective mental health awareness programmes specific to people of various age-groups in the Chinese population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to the Jardine Matheson Group for their generous support and contribution in programme implementation, liaison, and data collection. We are also grateful to the research participants who took time from their busy schedules to participate in the study, and to the teachers who facilitated the data collection process. Without their participation and help, this study would not have been possible. This paper is written with referencing to the ‘10th Anniversary Evaluation Report’ (Health in Mind Programme, Kwai Chung Hospital, 2013), and we would like to thank Ms Silvia S. W. Lee, clinical psychologist of the programme, for leading the evaluation study.

Declaration

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust 1997;166:182-6.

- Jorm AF. Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:396-401.

- The World Health Report 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002;1:16-20.

- Watson AC, Otey E, Westbrook AL, Gardner AL, Lamb TA, Corrigan PW, et al. Changing middle schoolers’ attitudes about mental illness through education. Schizophr Bull 2004;30:563-72.

- Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:907-22.

- Watson AC, Corrigan P, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophr Bull 2007;33:1312-8.

- Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol 2004;59:614-25.

- Wong DF, Tsui HK, Pearson V, Chen E, Chiu ES. Changing health beliefs on causations of mental illness and their impacts on family burdens and the mental health of Chinese caregivers in Hong Kong. Int J Ment Health 2003;32:84-98.

- Siu BW, Chow KK, Lam LC, Chan WC, Tang VW, Chui WW. A questionnaire survey on attitudes and understanding towards mental disorders. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2012;22:18-24.

- Chow Y. Stigma a stumbling block in Hong Kong’s efforts to promote mental well-being. 2015. Available from: http://www.eoc.org.hk/ EOC/Upload/UserFiles/File/thingswedo/eng/twdpwm0054.htm. Accessed 14 Jan 2016.

- Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:2011-9.

- Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry 2003;182:342-6.

- Pinfold V, Stuart H, Thornicroft G, Arboleda-Florez J. Working with young people: the impact of mental health awareness programmes in schools in the UK and Canada. World Psychiatry 2005;4(S1):48-52.

- Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol 1999;54:765-76.

- Heijnders M, Van Der Meij S. The fight against stigma: an overview of stigma-reduction strategies and interventions. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:353-63.

- Watson AC, Corrigan PW. Challenging public stigma. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005: 281-95.

- Pettigrew TF. Intergroup contact theory. Annu Rev Psychol 1998;49:65-85.

- Chan JY, Mak WW, Law LS. Combing education and video-based contact to reduce stigma of mental illness: “The Same of Not the Same” anti-stigma program for secondary schools in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med 2009;68:1521-6.

- Chow Y, Lee CC. Stigma towards individuals with mental illness: a comparison of staff members of two non-governmental organizations and a mental hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Kwai Chung Hospital; 2009. In press.

- Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Public beliefs about schizophrenia and depression: similarities and differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38:526-34.

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. Am J Sociol 1987;92:1461-500.

- Song LY, Chang LY, Shih CY, Lin CY, Yang MJ. Community attitudes towards the mentally ill: the results of a national survey of the Taiwanese population. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2005;51:162-76.

- Taylor SM, Dear MJ, Hall GB. Attitudes toward the mentally ill and reactions to mental health facilities. Soc Sci Med Med Geogr 1979;13D:281-90.

- Hospital Authority’s E.A.S.Y. Programme: 3-year efforts proven effective to encourage early treatment for early psychosis [press release]. Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2005 Mar 23.

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. How children stigmatize people with mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2007;53:526-46.

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv 2012;63:963-73.

- Schachter HM, Girardi A, Ly M, Lacroix D, Lumb AB, van Berkom J, et al. Effects of school-based interventions on mental health stigmatization: a systematic review. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2008;2:18.

- Health in Mind Programme, Kwai Chung Hospital. 10th Anniversary Evaluation Report. Hong Kong: Health in Mind Office, Kwai Chung Hospital; 2013.

- Watson AC, Miller FE, Lyons JS. Adolescent attitudes toward serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 2005;193:769-72.