Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:24-31

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr David YK Lau, MRCPsych (UK), FHKAM (Psychiatry), St. Paul’s Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Dr Alfred HT Pang, MRCPsych (UK), FHKAM (Psychiatry), Tai Po Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr David YK Lau, St. Paul’s Hospital, 2 Eastern Hospital Road, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 3586 9881; Fax: (852) 3586 9882; E-mail:drdavidlau@yahoo.com.hk

Submitted: 9 January 2007; Accepted: 6 March 2007

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory, a 66-item instrument that measures both positive and negative appraisals of the caregiving experience.

Participants and Methods: The reliability of the Chinese Experience of Caregiving Inventory was examined in a group of caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders admitted to a gazetted psychiatric inpatient unit in Hong Kong. Construct validity was evaluated by correlational analyses with the Chinese versions of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire and General Health Questionnaire–12.

Results: A total of 129 caregivers were recruited — 63% of the index patients of these caregivers suffered from schizophrenia, 17% suffered from affective disorder, and the remainder from other functional psychotic disorders. Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and the item-scale correlation of the Chinese version of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory were satisfactory. Analysis of the 10-factor solution yielded findings comparable to the original version. Construct validity was satisfactory as there were significant correlations between positive and negative appraisals of the Experience of Care giving Inventory with the Chinese versions of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire and General Health Questionnaire–12 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: The results suggest that the Experience of Caregiving Inventory could be applied in the Chinese population. Future studies using this Inventory to evaluate the caregiving experience of severe mental disorders should be cons

Key words: Caregivers/psychology; Mental disorders; Questionnaires; Schizophrenia

摘要

目的:檢視以66小項計算有關照顧經驗的中文版「照顧經驗量表」的心理測量特性。

參與者與方法:對象為一班重性精神病患者的照顧者; 患者入住香港精神科觀察治療中心。照顧者參與「照顧經驗量表」測試,從而檢視這種評估的可信性,並使用「適應問卷」和「一般健康問卷( 12小項) 中文版和相關分析評估結構效度。

結果:研究共招募129名照顧者參與。在他們照顧的患者中, 63%患有精神分裂症、17%患情感障礙、其餘則患有功能性精神異常。「照顧經驗量表」中文版在重試信廈、內部一致性信度,以及項目與量表的相關系數皆令人滿意,而因素分析發現10個主要成份跟英文版相若。此外, 「照顧經驗量表」、「適應問卷」和「一般健康問卷( 12小項) 」 中文版中的小項得分,與照顧者正面及負面的評價均有顯著的正比關係,顯示這三種工具都有良好的結構效度(p < 0.001 )。

結論:結果顯示「照顧經驗量表」中文版對華人適用,並建議使用此量表進一步研究重性精神病患者的照顧者經驗。

關鍵詞:照顧者/心理學、心還異常、問卷調查、精神分裂症

Introduction

De-institutionalisation and the shift towards community care of persons with severe mental disorders have led to increased concern over the effect on relatives, the informal caregivers. Family members have been reported to experience feelings of loss and grief,1 uncertainty, and emotions of shame, guilt, and anger.2 The consequence of this caregiving role is known as the ‘caregiving burden’. Hoenig and Hamilton3 classified these burdens into objective and subjective subtypes. Objective burden (OB) refers to the adverse events on the household and the general disruption of the life of a family member owing to the patient’s illness. Other researchers4,5 consider symptoms and dysfunction as an OB, and assess the caregivers’ distress (subjective burden [SB]) in relation to each particular problem or difficulty associated with the illness of respective patients. Subjective burden refers to the caregiver’s personal appraisal of the situation and the extent to which individuals perceive that they are carrying a heavy load.3,6 There are 3 approaches to measuring SB. The first is directly tied to the previously assessed OB, as recalled by the caregiver,4,5 and excludes distress arising from wholly ‘non-objective’ aspects of caregiving.7 The second is a global rating of the distress felt by the caregiver as a result of the patient’s illness.3,8 In the third approach, SB is assessed from affective dimensions, such as shame, stigma, guilt, resentment, grief, and worry.9 A review of the assessment on caregiver burden10 showed that there were disagreements with regard to both the definition and the way that it could be measured.

Szmukler et al7 recently developed a ‘stress-coping’ model to explain the effects of life stressors on physical health. Under this model, the caregiving experience is conceptualised as an appraisal of its demands. Mediating factors, such as quality of family relationships and social support, may influence the appraisal. Outcomes, in terms of psychological or physical well-being, are regarded as the result of an interaction between the caregivers’ appraisal and their coping strategies.7 According to this theory, outcome can be changed by targeting the intervention at the caregivers’ coping strategies and their appraisal of the demands. Based on this model, Szmukler et al7 developed a self-report measure of the experience of caregiving for a family member with a serious psychiatric illness. The Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) assesses both the positive and the negative aspects of caregiving.

There has been a dearth of information regarding burden in caregivers of persons suffering from severe mental disorders in Hong Kong and no well-established Chinese instrument for measuring such a burden has been validated. Previous reviews6,11 highlighted the methodological problems of previous studies on the caregiving burden. These included problems with the psychometric properties of the burden instrument, inconsistent use of theoretical and operational definitions, and the heterogeneity of the studied subjects. Sampling bias was another issue; some studies recruited caregivers from self-help groups, whose level of commitment and caregiving burden may be different from that of other relatives of patients. The lack of a theoretical framework was another major limitation. Finally, many studies were cross-sectional in nature, which limited their ability to assess the variation of burdens over time. Moreover, the direction of association between the independent variables and caregiver burden could not be ascertained. In the present study, the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Experience of Caregiving Inventory (CECI) were examined. It was hoped that the purpose- specific CECI would help improve assessment of caregiver burdens (contributing to research in this locality), even when it involved caregiving of persons with severe mental disorders.

Patients and Methods

Translation of Experience of Caregiving Inventory

Approval was obtained from the original author7 to translate the ECI from the English version into Chinese, and was performed by a professional independent translator. A second independent translator, with a university degree in the study of English, back-translated the Chinese version into English. The authors then compared the English and Chinese versions. Discrepancies were thoroughly discussed and resolved by joint agreement between the 2 translators.

Subjects and Setting

All patients who were admitted to the New Territories East Psychiatric Observation Unit of Tai Po Hospital in Hong Kong between December 2001 and February 2002 were screened. This gazetted unit provides care to all adult and adolescent patients in the New Territories East area of Hong Kong with a population of over 900,000 in 2001 (Census and Statistics Department). During this period, caregivers were invited to participate in assessing the psychometric properties of the ECI. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the index patient had to have (a) schizophrenia or a related disorder (ICD-10 codes F20-F29),12 or (b) severe affective disorder (F30.1,2,9, F31.1,2,9, F31.4-5, F32.2-3, F33.2-3) as assessed by 2 qualified psychiatrists in a clinical ward round within 1 week of admission; patients readmitted during the study period were assessed as per first admission only; (ii) the index patient had to be ethnically Chinese and currently aged between 15 and 65 years; (iii) the index patient had no co-morbid mental retardation, severe dementia, history of active substance misuse, mental disorders due to brain damage, or dysfunction due to physical disease; and (iv) the index patient had to be able to give informed consent to participate in the project.

A main caregiver who had most contact with each patient was recruited. Eligible caregivers had to be over 15 years of age and in ‘reasonable’ contact with the participant, which was defined as face-to-face or phone contact at least twice per week. Caregivers were invited by telephone to attend for interviews. The interviews were conducted within 2 weeks of the patient’s admission, by either the author or the clinical psychologist in-charge at the hospital, or by 2 trainee clinical psychologists (who were also well-experienced with the instruments). The trainee psychologists were trained in the use of the questionnaires by the author and the clinical psychologist in-charge. Both the patients and caregivers gave written informed consent after the study had been fully explained to them.

Assessment Tools

Caregivers reported their own socio-demographic information, including age, gender, kinship, marital status, education level, years of formal education received, whether they lived with the index patient, type and area of housing, number of people living in the same household, occupation, and family income. The patient also provided demographic information including age, gender, marital status, education level, years of formal education, occupation, and living conditions. The direct contact time between the relative and the patient per week was recorded.

Experience of Caregiving Inventory

This 66-item self-report questionnaire was originally developed for use with caregivers of patients with severe mental illness. It measures the caregivers’ appraisal of their respective experience under the stress-coping framework. The time frame was the preceding 4 weeks. It consisted of 52 items measuring 8 negative appraisal subscales, including: ‘difficult behaviours’, ‘negative symptoms’, ‘stigma’, ‘problems with services’, ‘effects on the family’, ‘need to back-up’, ‘dependency’, and ‘loss’. The remaining 14 items consisted of 2 positive appraisal subscales, including ‘positive personal experiences’ and ‘good aspects of the relationship’. Items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). The overall positive and negative scores were calculated by summation of these sub- scores. The scale is easy to administer and is based on a large number of relatives’ reports. The internal consistency (Cronbach α, 0.74-0.91) and construct validity7 are good. Experience of Caregiving Inventory and coping accounted for about 40% of the variance in the psychological distress of caregivers in the original study.

Chinese Ways of Coping Questionnaire

This is a 16-item short Chinese questionnaire13 that covers a broad range of cognitive and behavioural coping activities. Its development was based on the Ways of Coping scale.14 Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Internal consistency was moderate (Cronbach α, 0.49-0.77). Four factors were identified, including ‘rational problem-solving’, ‘seeking support and ventilation’, ‘resigned distancing’, and ‘passive wishful thinking’ during validation. The first 2 strategies could be subsumed under active problem-focused categories (‘rational problem- solving’, ’seeking support and ventilation’), while the last 2 were classified under avoidance categories. Chinese Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WOCQ) was adopted as a reference to assess construct validity of the ECI. Approval to use the questionnaire was obtained from the original author.

General Health Questionnaire

This is a self-report screening instrument for psychological morbidity.15 Subjects rate items on a 4-point Likert scale. A 12-item version16 was used to avoid overloading the subjects. The scale was based on the Chinese version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)–30, which has been independently validated.17 The GHQ-12 was adopted as a reference to assess construct validity of the ECI.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 10.0. The representativeness of the sample was assessed by comparing eligible patients who did not enter the trial with those who did, using a Chi-square test for categorical data and a Mann- Whitney U or independent t test (normal distribution) for continuous data. For the psychometric properties of the ECI, scale reliability including internal consistency (Cronbach α), item-scale correlation, and test-retest reliability were analysed. The principal components extraction procedure for factor analysis was used. Construct validity was measured by correlation of the ECI scores with the scores of GHQ and WOCQ. Approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Tai Po Hospital.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

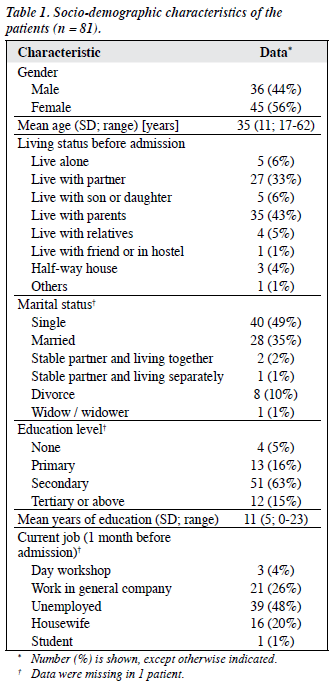

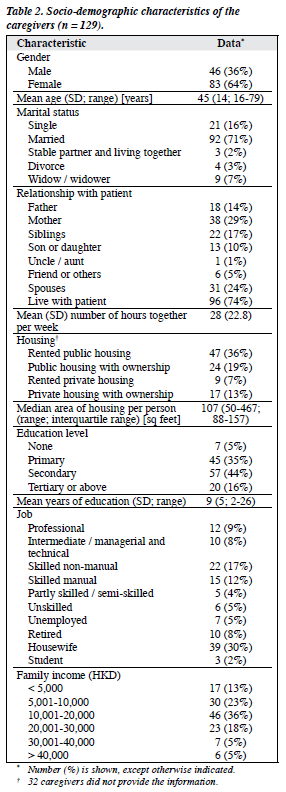

One hundred and eighty caregivers fulfilled the inclusion criteria; 13 patients were discharged before contact and 25 caregivers could not be contacted. Of the 142 caregivers available for the interview, 134 consented to be interviewed but 5 were excluded as they had difficulties in understanding the items or rating the responses. The overall response rate was 72% (n = 129). There was no significant age, gender, or diagnosis difference between patients who entered the study and patients who did not. There were also no significant age and gender differences between participating caregivers and non-participants. The socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and caregivers are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The median duration of illness was 364 weeks (interquartile range, 142-579 weeks).

Reliability of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory

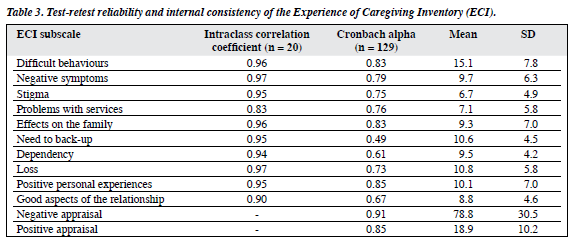

The 10 subscales were examined for reliability. During the initial phase, 20 caregivers were randomly invited to repeat the ECI questionnaire for test-retest reliability. The test- retest reliability of the subscales of the ECI was good, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.83 to 0.97 (Table 3). The Cronbach alpha of the ECI subscales ranged from 0.49 to 0.85, indicating moderate to satisfactory internal consistency. Three subscales, including the ‘need to back-up’ (Cronbach α = 0.49), ‘dependency’ (Cronbach α = 0.61), and ‘good aspects of the relationship’ (Cronbach α = 0.67) were moderate in terms of internal consistency. The internal consistencies of the overall positive and negative appraisals were good (Cronbach α = 0.85 and 0.91, respectively). The item-scale correlation ranged from 0.40 to 0.79 (p < 0.05) for all items except item 48, namely ‘her keeping bad company’ (item scale correlation = 0.27). There was also a positive correlation between positive and negative appraisals (r = 0.323, p = 0.003).

Factor Analysis of Experience of Caregiving Inventory

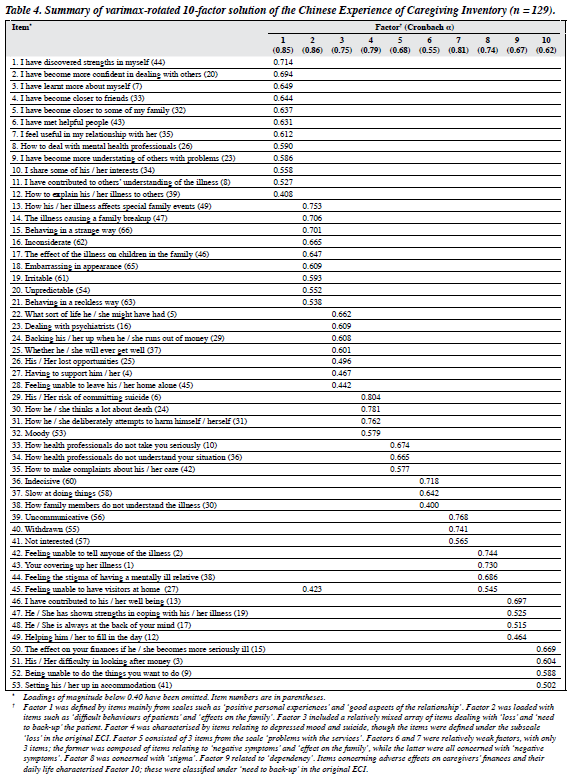

Because the 10 subscales of the appraisal of caregiving were based on the factor structure of the original ECI, which varied somewhat across populations, it was important to examine the reproducibility of the 10-factor solution in our Chinese caregivers’ responses to the CECI. A principal component analysis was performed on the item responses of caregivers, yielding 19 factors with eigen values that exceeded unity and that accounted for 71.5% of the variance. In order to compare the Chinese version with the original ECI, a 10- factor solution was chosen for analysis. This accounted for 54% of the variance. Items with a factor loading greater than 0.4 and with a loading of at least 0.1 greater than on any other factor were chosen, which was the same criterion as that applied by the original author.7 Table 4 summarised the factor structure of the ECI. Cronbach alpha of the 10 factors ranged from 0.55 to 0.86, indicating a moderate to satisfactory internal consistency.

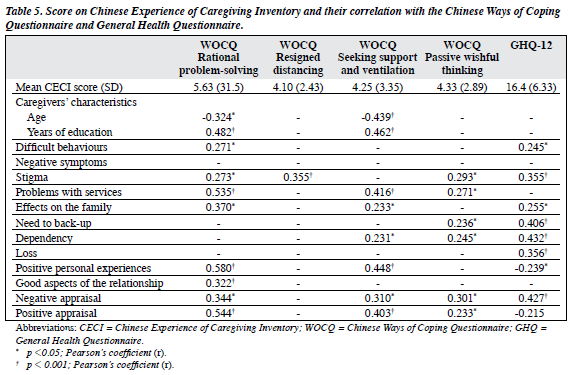

Caregivers’ Coping Characteristics and Their Correlation with Experience of Caregiving Inventory Scores

The scores of the Chinese WOCQ are summarised in Table 5. Regarding ways of coping, ‘rational problem-solving’ and ‘seeking support and ventilation’ showed a highly significant correlation with positive appraisal (r = 0.54, p < 0.001; r = 0.40, p < 0.001, respectively). This indicated that caregivers who practised ‘active problem-focused’ coping strategies appraised caregiving more positively. There was also a positive correlation between ‘passive wishful thinking’ and positive appraisal (r = 0.23, p = 0.04). Negative appraisal showed a positive correlation with ‘rational problem-solving’ (r = 0.34, p = 0.002), ‘seeking support and ventilation’ (r=0.31, p = 0.01), and ‘passive wishful thinking’ (r = 0.30, p = 0.01).

Association between Experience of Caregiving Inventory and General Health Questionnaire scores

The mean score on GHQ-12 was 16.4 (SD = 6.33). Correlation with the CECI (Table 5) showed a highly significant relationship with negative appraisal (r = 0.43, p < 0.001). There was a trend towards a negative correlation with the positive appraisal (r = -0.22, p = 0.05). Among the negative appraisal subscales, ‘stigma’ (r = 0.36, p = 0.001), ‘need to back-up’ (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), ‘dependency’ (r = 0.43, p < 0.001), and ‘loss’ (r = 0.36, p < 0.001) showed highly significant correlations with the GHQ.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the CECI is a useful instrument for measuring the appraisal of caregivers of patients with severe mental disorders in Hong Kong. The study found few significant correlations with socio-demographic and clinical variables. One interesting finding was the positive correlation between negative and positive appraisals of caregiving, a finding that was reported in a previous study.18 The construct validity of the ECI, which is based on the ‘stress coping’ model, was supported by the fact that caregivers’ psychological distress was predicted by the negative appraisal and ways of coping.

The reliability of the CECI proved to be satisfactory compared to the original ECI.7 The test-retest reliability and internal consistency of the 10 subscales was moderate to satisfactory. Item scale correlation for most items indicated a moderate-to-good correlation. A 10-factor solution was chosen as the factor structure for the CECI in order to make a comparison with the original ECI. Of the 10 CECI factors, 7 had at least 4 items, and were similar to those of the original ECI. This factor solution was further supported by the good internal consistency of the 10 subscales.

We found a positive correlation between ‘active problem-focused’ coping strategies, ‘rational problem- solving’, and ‘seeking support and ventilation’, with negative appraisal of caregiving. This finding has also been reported in patients with a first episode of psychosis.19 It is possible that caregivers who appraised negatively tended to adopt ‘active problem-focused’ coping strategies in order to cope. An alternative explanation is that those who more frequently adopted ‘active problem-focused’ coping strategies would appraise the caregiving experience both more negatively and more positively. This does not necessarily imply higher psychological distress, as the GHQ was negatively correlated with this type of coping strategy.

Scores on the GHQ were comparable to those of caregivers in other similar studies.7,20 Greater psychological distress was noted in caregivers who appraised caregiving more negatively, and those who adopted more avoidance coping strategies, such as ‘passive wishful thinking’, and less ‘active problem-focused’ coping strategies, such as ‘rational problem-solving’. This was consistent with findings in other studies that have used the same model.7,18,19,21

Limitations of this study included its cross-sectional design and potential sampling bias (only caregivers of acute in-patients were included). However, it served to assess the effect of acute mental and behavioural disturbance of patients on the caregiving appraisal and psychological distress of caregivers. Recruitment of day and outpatients for comparison might reduce this bias.

The CECI is a useful instrument for measuring the appraisal of caregiving of relatives of patients with severe psychiatric illness. The instrument is both acceptable and applicable, and its construct validity was proven with the use of the ‘stress-coping’ model. Preliminary factor analysis showed that its 10-factor solution was comparable to that of the original version. Appraisals of caregiving were closely related to coping strategies and the psychological distress of caregivers.

References

- Miller F, Dworkin J, Ward M, Barone D. A preliminary study of unresolved grief in families of seriously mentally ill patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990;41:1321-5.

- Schene AH, van Wijngaarden B, Koeter MW. Family caregiving in schizophrenia: domains and distress. Schizophr Bull 1998;24:609-18.

- Hoenig J, Hamilton MW. The schizophrenic patient in the community and his effect on the household. Int J Soc Psychiatry 1966;12:165-76.

- Platt S. Measuring the burden of psychiatric illness on the family: an evaluation of some rating scales. Psychol Med 1985;15:383-93.

- Tessler RC, Fisher GA, Gamache GM. The family burden interview schedule; manual. Amherst: Social and Demographic Research Institute, University of Massachusetts; 1992.

- Maurin JT, Boyd CB. Burden of mental illness on the family: a critical review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 1990;4:99-107.

- Szmukler GI, Burgess P, Herrman H, Benson A, Colusa S, Bloch S. Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996;31:137-48.

- Pai S, Kapur RL. The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. Br J Psychiatry 1981;138:332- 5.

- Reinhard SC, Gubman G, Horwitz AV, Minsky S. Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval Program Plann 1994;17:261-9.

- Schene AH, Tessler RC, Gamache GM. Instruments measuring family or caregiver burden in severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1994;29:228-40.

- 1 Baronet AM. Factors associated with caregiving burden in mental illness: a critical review of the research literature. Clin Psychol Rev 1999;19:819-41.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Diagnostic criteria research. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

- Chan DW. The Chinese Ways of Coping Questionnaire: Assessing coping in secondary school teachers and students in Hong Kong. Psychol Assess 1994;6:108-16.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

- Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 1979;9:139-45.

- Pan PC, Goldberg DP. A comparison of the validity of GHQ-12 and CHQ-12 in Chinese primary care patients in Manchester. Psychol Med 1990;20:931-40.

- Chan DW, Chan TS. Reliability, validity and the structure of the General Health Questionnaire in a Chinese context. Psychol Med 1983;13:363-71.

- Harvey K, Burns T, Fahy T, Manley C, Tattan T. Relatives of patients with severe psychotic illness: factors that influence appraisal of caregiving and psychological distress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:456-61.

- Tennakoon L, Fannon D, Doku V, O’Ceallaigh S, Soni W, Santamaria M, et al. Experience of caregiving: relatives of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:529-33.

- Ohaeri JU. Caregiver burden and psychotic patients’ perception of social support in a Nigerian setting. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:86-93.

- Tucker C, Barker A, Gregory A. Living with schizophrenia: caring for a person with a severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:305-9.