Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:17-23

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Gregory KL Mak, Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Dr Frendi WS Li, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Prof Peter WH Lee, Department of Psychiatry, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr GKL Mak, Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po

Hospital, Tai Po, Hong Kong, China. Tel: (852) 2607 6731;

E-mail:gregorymak@graduate.hku.hk

Submitted: 23 February 2007; Accepted: 27 March 2007

Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the functional and clinical status of a group of Chinese schizophrenic patients after treatment with individually tailored psychological treatment over a 9-month period.

Partients and Methods: Thirty six 15- to 32-year-old Chinese schizophrenic patients were recruited into the study from 2001 to 2002. The patients were randomly assigned into treatment and waitlist groups. At baseline their pre-treatment clinical status, social functioning, and other clinically relevant parameters were assessed. The psychological treatments were conducted by 2 experienced clinical psychologists and assessed by face-to-face interviews.

Results: After the treatment period, outcome measures supported the use of adjuvant psychotherapy in the routine treatment programme for subjects with schizophrenia; both positive and negative symptoms improved compared to baseline status (p < 0.001).

Conclusions: The findings support the use of psychotherapeutic interventions to promote better adaptation to the psychotic disorder.

Key words: Behavior therapy; Cognitive therapy; Psychotherapy; Schizophrenia; Schizophrenic psychology

摘要

目的:視察一批精神分裂症華裔患者於為期九個月的個人心理治療後,其功能和臨床上特點的轉變。

患者與方法:研究於2001 至2002年間進行,對象為36名15至32歲的華裔精神分裂症年青患者。他們隨機被分配為「治療組」 及「等候組」,並於接受治療前為患者的臨床狀態、社會功能和其他臨床參數先作評估。然後由兩名資深尿臨床心理學家以會面的形式與患者進行心理治療再作評估。

結果:研究結果顯示, 心理治療對常規治療精神分裂症有輔助作用, 也令陽性及陰性徵狀較未接受治療前有顯著改善( p < 0,001 )。

結論:研究結果證明心理治療有助改善精神失常的治療效果。

關鍵詞:行為治療、認知治療、心理治療、精神分裂症、精神分裂心理學

Schizophrenia is one of the most widely studied mental disorders. Psychiatrists have been struggling to find the best treatment model to optimise recovery and minimise chance of relapse. Conventional antipsychotic medications are successful in controlling positive symptoms, but have undesirable side-effects.1 In addition, the 2-year relapse rate is still around 30 to 50%.2,3 The introduction of second- generation anti-psychotics has renewed hope for patients with schizophrenia. Randomised controlled trials have shown that such medication is better at controlling positive symptoms, extrapyramidal side-effects, and possibly negative symptoms too.4 However, the newer drugs increase the risk of metabolic syndrome and the associated weight gain jeopardises treatment adherence.5 Although medications attenuate the severity of the most florid symptoms in schizophrenia, negative symptoms (interfering with normal functioning) still persist. This has posed great difficulties for patients to return to society. Because of these constraints, emphasis on psychosocial treatment models, as part of the multi-facet rehabilitation programme in the treatment of schizophrenic patients, should not be neglected.

Efficacy of psychological treatments has been evalu- ated in many studies. Family therapy, based on the notion that clinical outcomes of schizophrenia are affected if the family exhibits highly expressed emotions, is reported to reduce relapses.6 Studies also suggest that social skills training confers significant benefits by reducing hospitalisation and family burdens.7,8 Similarly, a work-related skills training programme in Hong Kong demonstrated success in securing jobs.7 Cognitive behavioural treatment showed promise in that dysfunctional information processing of schizophrenic patients could be successfully tackled.9 Despite many such studies, there has been no systematic study to evaluate the efficacy of psychotherapy used in combination with medication, in the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong.

We set out to study an individually tailored psychological treatment programme (various psychotherapeutic modalities to optimise the psychosocial outcomes of young schizophrenic patients). Our aim was to evaluate the evolution of clinical parameters in schizophrenic patients receiving psychological treatment.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were young adults with diagnosis of schizophrenia, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria, and actively being followed up in local psychiatric settings at the time of the study. Public and private psychiatric clinics were notified and encouraged to refer their patients for the psychological treatment programme. Recruitment began from January 2001 through December 2001. A total of 53 patients were interviewed and screened by the project clinical psychologists for possible inclusion. Inclusion criteria were: being diagnosed as having schizophrenia according to DSM-IV criteria, age of 15 to 32 years, Cantonese speaking, willing to participate in the study and attend the specified follow- up treatments, consent to continue seeing their psychiatrist for ongoing psychiatric treatment, and the absence of any other psychiatric and medical co-morbidity. No fees were levied for all stages of the psychological treatment, which was supported by a private donation. A total of 48 patients consented to participate.

Procedure

In the presence of family members (usually 1 parent), the first author interviewed each patient for baseline mental status assessment, demographic background, illness history, family involvement, drug attitudes, and insight into their illness. Following baseline assessment, each patient was randomly assigned into the psychotherapeutic treatment or waitlist groups. Two experienced clinical psychologists provided the psychotherapy at the Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong. The follow-up schedule and specific treatment plan for each subject was designed based on clinical needs, progress, and problems identified. Each patient was seen at least once (about 1 hour) every 2 weeks during the treatment period. Patients with extra needs were allocated more treatment sessions, after the basic psychological treatment package.

A blinded, well-trained independent assessor kept attendance records and monitored progress at 3-monthly intervals. The whole programme lasted about 1.5 years when the treatment and follow-up assessments for both groups were completed. Twelve subjects (1 from the treatment group and 11 from the waitlist group) dropped out. The reasons given included: the hospital was too far away, the therapy was too long/drawn-out, involvement in forensic issues, and disease relapse. Finally, 36 subjects completed the study, 23 in the treatment group and 13 in the waitlist group, and their data were collected and analysed. Changes in clinical parameters were compared at the baseline and after psychological intervention.

Psychological Treatments

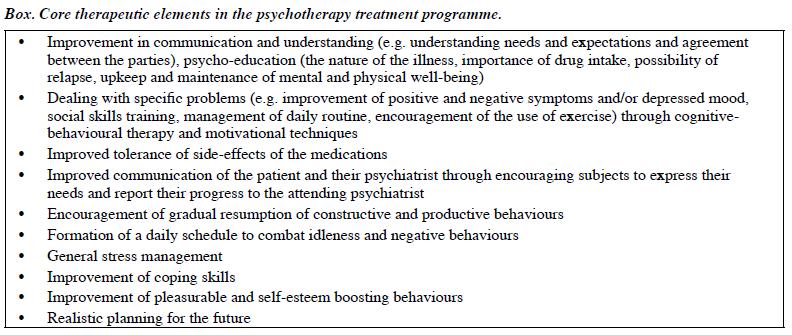

Psychological treatment was based on clinical assessments of the subjects’ presenting problems and needs; the orientation being cognitive-behavioural. The 2 project psychologists had periodic case consultations with each other to ensure their therapy coverage and approach were compatible. The core therapeutic elements are summarised in the Box.

Assessment Schedule

At baseline, each subject was evaluated with all the assessment tools. The psychological treatment lasted 9 months and there was a 6-month follow-up. Assessments were scheduled at a 3-monthly interval, until the 15th month. The 3rd- and 9th-month progress assessed insight, attitude to drugs, family problems, positive and negative symptoms. The waitlist subjects went through all the usual assessments as stated but they had 2 additional separate assessments during the 6-month waiting period before treatment baseline. The whole study period lasted for 15 months (21 months for waitlist group).

Assessment Tools

Present State Examination 9th Edition (PSE-9) was used to assess the presence and severity of positive symptoms over the past month. The PSE-9 consists of 18 sections, but only the sections relevant to the assessment of positive symptoms were selected (depersonalisation and derealisation, perceptual disorders, thought disorders, delusions, and hallucinations).10-13

In the Family Interview Schedule (FIS), family members were asked to report on various aspects of the patient’s daily behaviours and activity pattern. The informant’s perception and feelings about the respective illness were also elicited.13 The FIS had already been used locally and internationally in the long-term follow-up study of schizophrenia.14,15

The Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) measured depressed mood and its accompanying symptoms. A total of 21 depressive symptoms were listed and a Chinese version of the BDI was used, the reliability and validity of which had been tested.16,17

The Broad Rating Scale (BRS) was the same as the version used in the long-term follow-up study on schizophrenia coordinated by the World Health Organization.13 The Global Assessment of Functioning and Symptoms was used to rate respective subjects on the basis of their symptoms and disability/impairment.13,18 The examiners rated their overall impression of subjects during each consultation and the global impairment of symptoms and function.

The Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS) was designed to evaluate specific areas of functioning; items were classified into 9 areas with 5 levels of ratings on each subject’s level of functioning and/or impairment. The areas assessed were: social functioning, subjective sense of disability, household, marital, and sexual role. The reliability and validity of this scale were documented.13,19

The Insight Scale (IS) consisted of 8 statements assessing 2 categories of insight. Overall insight about the illness and view regarding treatments were assessed. Items were listed and the patients asked to rate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement. Apart from the total score, each item of the scale could also be analysed separately to provide important information pertaining to specific aspects of insight.20

The Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI), devised by TP Hogan, AG Awad and R Eastwood, was used to evaluate attitudes towards drug use as part of insight assessment. The scale consists of 10 self-reported assessment items on various aspects of drug use (e.g. rationale for drug treatment, side-effects, tolerability, etc). Respondents were asked to indicate the level of their agreement or disagreement with each item. Good validity and reliability of the scale had previously been reported.21

The Perceived Stress Scale–10 (PSS-10) targets perceived stress over the past month. The scale originally consisted of 14 items designed to explore subjective appraisals of events. We adopted its short form (only 10 items) which has similar power and reliability to the longer version. Scoring ranged from 0 to 3. The total PSS-10 score was calculated as a measure of overall stress. Good validity and reliability of the scale had been reported.22

Results

Demographic Characteristics

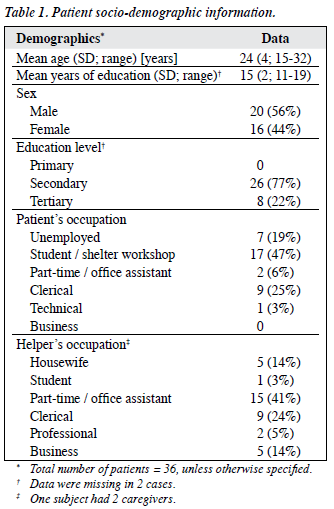

Forty eight patients were recruited; 12 dropped out and so 36 completed the study. The socio-demographic data of the latter patients are summarised in Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Psychiatric Symptomatology

Among the 36 patients assessed with PSE-9, 8 had symptoms of derealisation and/or depersonalisation, 12 had perceptual disorders, 24 had delusion symptoms, 17 had thought disorder, and 19 had hallucinations.

According to informants’ reports as measured in the FIS, 14% had visual hallucination, 28% were reported to do strange things, 11% complained that others were talking about them. Nineteen percent told the informant they heard others talking about them, 36% were suspicious, and 28% complained that they were made to do things they did not want. Twenty four percent felt strange things happened inside their body, and 17% were preoccupied with strange ideas and thoughts.

Informants reported that 39% of the patients always idled at home, 16% stayed in one position without any other movements, and 40% moved and acted slowly. Another 40% experienced difficulties in carrying on a conversation, 20% were not interested in companionship, and nearly half had little interest in social activities. Sixty percent were emotionally detached, 10% got angry easily and had broken things, 3% were involved in fights, and nearly 40% had threatened to tell people off. The great majority (92%) of the patients experienced mild depressive symptoms (mean score = 18) in accordance with the scoring scale defined by BDI.

Psychosocial Functioning

Less than 20% of the patients had a job or contributed to family income. If they had a job, it was usually temporary and usually entailed a low salary. At baseline, both treatment and waitlist groups had moderate impairment of symptoms, including: flat affect, circumstantial speech (mean score = 57) and moderate disability in social, occupational, or school functioning (having no friends and unable to keep a job) with a mean score of 54, according to the BRS.

The baseline mean score of the perceived stress level was 20, compared to the mean population score of 13. As assessed by the DAS, the baseline functioning demonstrated mild-to-moderate levels of impairment. In particular, patients were noted to have impaired social functioning (mean = 1.6), subjective sense of disability (mean score = 2.5), household role (mean score = 0.74), and an impaired sexual role (mean score = 0.8).

The baseline assessment showed that they had a moderate lack of insight (mean = 10) using the IS. They had little faith in their treatment (mean = 14, total score =19) as noted in the DAI, and 44% regarded themselves as being mentally well and 61% did not agree to having a diagnosis of mental illness. Moreover, 11% thought that they should take medication only when there was disease relapse.

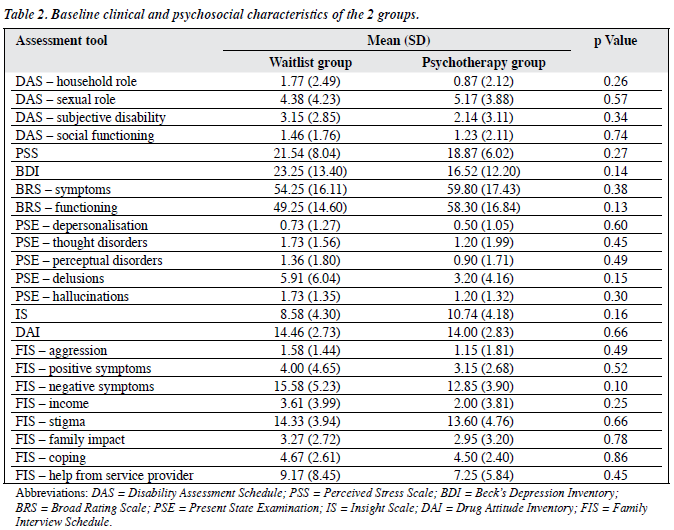

Comparing the baseline clinical status of the treatment and the waitlist groups, there were no major differences between them (Table 2). Regarding all clinical parameters in the waitlist group, there were also no significant differences between the first assessment and a subsequent 6-month assessment (immediately before treatments, p = not significant). Since prior to treatment, the waitlist group did not show any significant changes in clinical status over time, and there were also no significant differences between the groups, assessment of the psychosocial effects of treatment was made on the basis of aggregate results of both the treatment and the waitlist groups after completion of all treatments.

Baseline Versus Outcome Evaluation at the 3rd Month into Treatment

All subjects had global improvement in their symptoms and function (p < 0.001). Significant reductions were noted in positive symptoms including: depersonalisation (p = 0.04), delusions (p = 0.001), hallucinations (p = 0.002), thought disorders (p < 0.001), and perceptual disorders (p < 0.001). Patients’ families, however, did not notice significant changes in positive symptoms after (p = 0.06), though the informants did report reductions in aggressive behaviour (p = 0.001). Patients had a lower depression score after 3 months (p = 0.004). Other indices, including social functioning (p = 0.08), household roles (p = 0.45), subjective disability (p = 0.30) and sexual roles (p = 0.70), perceived stress level, insight and drug attitudes were no different.

Baseline Versus Outcome Evaluation at the 9th Month into Treatment

The patients continued to show global improvement in symptoms and functionality (p < 0.001). The 5 positive symptom indices all improved (p < 0.001). The informants also noticed a positive change in terms of psychotic symptoms (p < 0.01). Negative symptoms also improved (p < 0.002). Subjective improvements in perceived stress levels (p = 0.01) were reported. Other improvements included social functioning (p < 0.001) and subjective disability (p = 0.03).

Baseline Versus Outcome Evaluation at the 6th Month after Completing Treatment

Subjects continued to show significant global improvement in their symptoms and functioning (p < 0.001), as did psychotic symptoms (p < 0.001). Informants reported improved control of positive symptoms (p = 0.002), aggressive behaviour (p < 0.001), and negative symptoms (p < 0.001). Patients were less depressed (p = 0.02). Improvements in social functioning (p = 0.002) and subjective disability (p < 0.001) noted previously were maintained. Insight (p = 0.20) and attitudes to drugs (p = 0.67) remained the same.

Discussion

All recruits fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV for schizophrenia. After excluding 3 subjects with co-morbid psychiatric illnesses, all patients in the study had only a single diagnosis of schizophrenia. At the time of recruitment, many still had psychotic symptoms. Informants (mostly parents) also confirmed that the patients were still having hallucinatory experiences. In contrast to other local studies23 reporting good symptomatic control in schizophrenic patients in general, for this younger group of patients, medications alone did not seem to have achieved optimal effects. Assessment of patient insight and attitudes towards drugs suggested a high possibility of poor drug adherence; there being a rather negative attitude towards drug intake with a correspondingly poor insight into their illness. About half of the patients were also severely impaired by negative symptoms, indicating that they were either poorly treated or neglected, which may explain the relatively long mean illness duration. Ratings of global clinical status indicate that the patients suffered moderate levels of symptoms and impairments.

Pre-treatment clinical findings indicated that the majority of patients suffered negative symptoms and functional handicap, indicating the need for more targeted treatment in these areas, particularly as non-intervention did not reveal improvements in the clinical status. The clinical findings in the waitlist group testified to this observation. After waiting for 6 months, these subjects did not show any significant change in previously documented clinical status.

The overall results showed improving trends in the clinical and functional status of the psychological treatment group. More significant improvements were noted in global symptoms and functioning, as well as perceived stress level. These preliminary data support the integration of psychological treatment as part of the management protocol for patients with first-onset schizophrenia.

During treatment sessions, both psychologists repeatedly tried to remind patients to adhere to their prescribed medications. When doubts were encountered, specific therapeutic interventions were targeted towards corresponding patient attitudes and medications, with efforts to rectify any specific distortions or erroneous beliefs. Patients were likely to comply better with medication instructions, after developing better rapport with their psychologists. Interestingly, while compliance behaviour improved, insight and attitudes towards medications were more difficult to change. The current study indicates that drugs were largely instrumental in controlling positive symptoms in these patients, and that psychotherapy merely augmented this effect, despite a lack of conviction on the part of the recipients.

A gradual improvement in negative symptoms (present at baseline) was noted after commencement of the psychosocial treatment alongside regular intake of medications. This seemed to support the use of adjunctive psychotherapy with conventional drug treatment. However, the improvements were moderate and seemed to reach a plateau after the first 9 months of treatment. By improving negative symptoms, these patients probably regain some functioning potential, lessen stress and the burdens that their families were facing.

Functional status is a direct way of revealing how and to what extent schizophrenic illness disables the afflicted. With the commencement of psychotherapy, there were significant improvements in functioning. The lack of robust improvements in insight may be related to the relatively short duration of the psychotherapy sessions, as well as the small number of study patients. Further and more deliberate therapeutic work is indicated to improve insight. The validity of insight measurement in local settings should also be questioned, since it is a notoriously multi-dimensional concept and mental state–dependent.

Ideally, patients and their caregivers should gain from the psychological treatment, which stresses essential skills required to become less dependent on long-term professional help. If protective and vulnerability factors could be ascertained, psychotherapy could be started early in the course of schizophrenia. Overall our results suggest that psychological treatment is useful in alleviating positive symptoms together with drugs, reduce the severity of negative symptoms and depression, improve social functioning, and relieve stress.

Due to the limitation of resources and time constraints, our study was only carried out for one and a half years. The small number of patients studied became the major limiting factor in carrying out statistical comparisons. The heterogeneity of clinical disease states also contributed to the difficulties of getting consistent data, strictly in accordance with the original schedule. The patients tended to have limited attention spans and their interests were difficult to maintain over the long run. As most of the dropouts were from the waitlist group, it was not practical to compare the characteristics of dropouts with those who completed the treatment. However, it was reasonable to assume that psychological treatment should be implemented as early as possible to enhance maximal benefits.

Despite the above constraints, our study indicates that psychotherapy is effective in improving treatment effects following first-onset schizophrenia. As the beneficial effects are maintained after completion, psychological intervention should be considered as an integral part of continuous holistic management.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their most grateful appreciation and thanks to the generous support and funding by the Zee Foundation.

References

- Gerlach J, Behnke K, Heltberg J, Munk-Anderson E, Nielsen H. Sulpiride and haloperidol in schizophrenia: a double-blind cross-over study of therapeutic effect, side effects and plasma concentrations. Br J Psychiatry 1985;147:283-8.

- Hogarty GE, Goldberg SC, Schooler NR. Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients. III. Adjustment of nonrelapsed patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974;31:609-18.

- Hogarty GE, Greenwald D, Ulrich RF, Kornblith SJ, DiBarry AL, Cooley S, et al. Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family, II. Effects of adjustment of patients. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:1514-24.

- Curran MP, Perry CM. Spotlight on amisulpride in schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 2002;16:207-11.

- Llorca PM, Chereau I, Bayle FJ, Lancon C. Tardive dyskinesias and antipsychotics: a review. Eur Psychiatry 2002;17:129-38.

- Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Baeuml J, Kissling W, Engel RR. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia—a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:73-92.

- Tsang HW, Pearson V. Work-related social skills training for people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Schizophr Bull 2001;27:139-48.

- Marder SR. Management of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57(Suppl 3):9-13,47.

- Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001;189:278-87.

- Wing JK, Nixon JM, Mann SA, Leff JP. Reliability of the PSE (ninth edition) used in a population study. Psychol Med 1977;7:505-16.

- 1 Luria RE, Berry R. Reliability and descriptive validity of PSE syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979;36:1187-95.

- Rodgers B, Mann SA. The reliability and validity of PSE assessments by lay interviewers: a national population survey. Psychol Med 1986;16:689-700.

- Sartorius N, Gulbinat W, Harrison G, Laska E, Siegel C. Long-term follow-up of schizophrenia in 16 countries. A description of the International Study of Schizophrenia conducted by the World Health Organization. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996;31:249-58.

- Lee PW, Leung PW, Fung AS, Low LC, Tsang MC, Leung WC. An episode of syncope attacks in adolescent schoolgirls: investigations, intervention and outcome. Br J Med Psychol 1996;69:247-57.

- Chua SE, Lam IW, Chen EY, Lee PW, Lieh-Mak F, Tai KS, et al. Asymmetric lateral ventricular enlargement in Chinese with 1st episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2002;57:123-4.

- Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychol Assess 1998;10:83-9.

- Bouman TK, Luteijn F, Albersnagel FA, Van-der-Ploeg FA. Some experiences with Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). Gedrag Tijdschrift voor Psychologie 1985;13:13-24.

- Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM- IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:1148-56.

- World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO/DAS) Albany, NY, US: World Health Organization 1988; viii:88.

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Drury V, Healy J, Macmillan F, Slade M. A self- report Insight Scale for psychosis: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994;89:62-7.

- Cheng HL, Yu YW. Validation of the Chinese version of “the Drug Attitude Inventory” [in Chinese]. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 1997;13:370- 7.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385-96.

- Lee PW, Lieh-Mak F, Yu KK, Spinks JA. Pattern of outcome in schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991;84:346-52.