Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2007;17:55-63

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Sandra SM Chan, MRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Dr Edwin PF Pang, MRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Tai Po Hospital, New Territories East Cluster, Hong Kong, China.

Prof Helen FK Chiu, FRCPsych, FHKAM (Psychiatry), FHKCPsych, Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China.

Address for correspondence: Dr SSM Chan, Department of Psychiatry, Ground Floor, Multi-centre, Tai Po Hospital, 9 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, New Territories, Hong Kong, China.

Tel: (852) 2607 6025; Fax: (852) 2667 1255; E-mail: schan@cuhk.edu.hk

Submitted: 29 March 2007; Accepted: 15 May 2007

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the validity of the best-estimate method for making psychiatric diagnoses and determine potential psychosocial risk factors in a cohort of Hong Kong Chinese who attempted suicide.

Participants and Methods: Seventy-one persons attempting suicide and their proxy-informants were interviewed separately to ascertain each patient's diagnosis (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition Axis I diagnosis), psychosocial profile, and life circumstances surrounding the index suicide attempt.

Results: There were substantial levels of agreement, high sensitivity and specificity on Axis I psychiatric diagnoses in subject-proxy pairs. Levels of subject-proxy agreement were substantial for other risk factor domains such as physical diagnoses, suicidal behaviour profile, social networking, and most life-event items. Fair-to-modest levels of agreement were observed in perceived well-being in general health, health service utilisation and life-events involving interpersonal conflicts within family and peer groups.

Conclusions: Results support the validity of the best-estimate methodology for assessing psychosocial risk factors and making psychiatric diagnosis among Hong Kong Chinese who attempt suicide.

Key words: Interview, psychological; Suicide, attempted

摘要

目的:檢視利用最佳估計方法學作出精神科診斷的有效性,以及研究導致香港華人企圖自殺的潛在心理社會風險因素。

參與者與方法:研究分別與71 位企圖自殺者及其諮詢者進行面談,並根據《精神疾病診斷和統計手冊》第四版(DSM-IV) 的第一軸精神科診斷對患者進行確診,和評估他們的心理社會概況和與企圖自殺指標有關的生活情況。

結果:在受訪患者及其諮詢者的對比中,在第一軸精神科診斷得出高度的一致性、敏感度及特異性。這種受訪患者及其諮詢者的一致性亦在其他風險因素範團中找到,例如軀體性疾病診斷、自殺行為概況、社交網絡和重大生活事件;對一般健康的看法、醫療服務使用程度及生活事件中涉及與家人及朋輩間人際關係的衝突則達普通至中度的一致性。

結論:研究結果支持最佳估計方法學於評估香港華人企圖自殺者的心理社會風險因素及作出精神科診斷的有效性。

關鍵詞:心理的面談、企圖自殺

Introduction

Suicide is a major public health problem affecting all nations. In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that more than one million suicide deaths occurred worldwide.1 Such a figure approximates to 14.5 suicide deaths per 100,000 people or one suicide death occurring every 40 seconds. From a public health perspective, suicide is the 13th leading cause of death worldwide and its detrimental effect has impacted all age-groups. To address the worldwide public health challenge posed by suicidal behaviour, there have been an increasing number of risk factor studies over the past few decades. The two main research approaches depend on community surveillance and psychological autopsy (PA). The PA approach, first developed and systematically described by Shneidman and Farberow in 1961,2 involves enquiries into individual suicide cases, using in-depth psychosocial interviewing to gather information from proxy-informants. The psychosocial interview is designed to elicit detailed psychological profiles and psychosocial circumstances leading to suicide deaths. This method is generally regarded as the hallmark for risk factor research into suicide, despite its unavoidable limitations such as recall and attribution bias of the informants.3 One indirect way to assess the validity of PA is by the ‘best-estimate methodology among suicide attempters’. This method involves living subjects with risk factors that are otherwise comparable to those of deceased persons. Another interviewer conducts the same interview with a proxy-informant related to the living subjects. The degree of agreement between the information obtained from the two sources can be determined. Suicide attempters, despite their heterogeneous clinical profiles, may serve as the best ‘proxy’ study population to our reference population of suicide completers.4

A few studies have examined the reliability of proxy information in various elderly and adolescent psychiatric populations,5,6 and suggest that informants under-report mood and substance abuse problems. Using the best- estimate method in late-life suicide attempters, Conner et al4 reported satisfactory proxy-subject agreement on diagnoses of mood and substance dependency diagnoses; and some degree of agreement on behavioural profiles of suicide attempters and certain aspects of social support and stressful life events.

Suicide research in Chinese communities is challenged by social taboos.7 The response rates for PA studies in Hong Kong Chinese were much lower than the rates encountered in Caucasian populations.8 The validity of PA in risk factor research for suicide in a Chinese sociocultural context has not been examined. This study set out to examine the validity of the best-estimate method for making psychiatric diagnoses and determine potential psychosocial risk factors in a cohort of Hong Kong Chinese who attempted suicide.

Methods

Study Participants and Recruitment

Our sampling included all suicide attempters, aged 18 to 64 years, presenting to the psychiatric consultation-liaison service of Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole Hospital (AHNH) in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region during a 1-year period starting from 1 June 2004. The regional hospital serves a catchment population of 400,000. All patients attending the AHNH Accident and Emergency Department or any general wards for a suspected suicide attempt are routinely referred to the psychiatric consultation-liaison service, where follow-up psychiatric treatments are offered as indicated. We adopted the definition of suicide attempt / non-fatal suicidal behaviour as in the WHO’s Multi-site Intervention Study on Suicidal Behavior. This states that “non-fatal suicidal behavior with or without injuries is a non-habitual act with a non-fatal outcome that the individual, expecting to, or taking the risk, to die or to inflict bodily harm, initiated and carried out with the purpose of bringing about wanted changes”.9 All potential subjects who met the inclusion criteria were first approached at the Accident and Emergency Department or general wards of AHNH. At the first encounter, potential subjects were only briefly introduced to this study, with verbal consent sought from the potential subjects for future correspondence. Potential subjects were approached again by the investigator, when they were mentally and physically fit for a research interview. Each subject was asked to nominate a knowledgeable proxy-informant to participate in the other part of this study. Written informed consent was sought from all subjects and their proxy-informants and the study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong and New Territories East, Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Research Interviews

Two trained psychiatrists conducted psychosocial interviews with the subjects and their proxy-informants. Both psychiatrists were trained in the methodology of PA at the University of Rochester’s Centre for the Study and Prevention of Suicide. Prior to this study, both interviewers tested their diagnostic agreement in a group of psychiatric in-patients of Tai Po Hospital. Independent diagnostic interviews using structured clinical interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I disorders (SCID-I/P10) were conducted in 20 conveniently recruited subjects. The diagnostic profile of these subjects included: major depressive disorder (MDD), bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, substance-related disorder, and adjustment disorder. The overall inter-rater reliability was satisfactory (kappa = 0.93; p < 0.001).

The two research psychiatrists conducted parallel and independent interviews with the subjects and their proxy- informants. The psychiatrist who interviewed the subjects adopted an all-source approach by reviewing the medical files of the subjects as well as information gathered in the research interviews. Another psychiatrist interviewed the proxy-informants and relied solely on the information obtained from them without referring to other clinical data such as medical files. Such an approach was adopted as we referenced findings from the subjects’ interviews as the ‘gold standard’ when evaluating the reliability and validity of proxy-informants’ reports. Each research interview took about 60 to 120 minutes.

As for the timing of the research interviews, a balance was struck to minimise the time lag between the index suicide attempt and the interview, so as to reduce recall bias, and optimise the time for subjects and proxy- informants to get over the emotional turmoil related to the index event. The mean time lag between the index suicide attempts and research interviews was 4.3 (SD, 5.7) weeks with the subjects and 7.7 (SD, 6.7) weeks with the proxy- informants.

Information gathered from research interviews was verified in consensus meetings held separately for both the subject and proxy-informant interviews. At the consensus meetings SCID diagnoses were scrutinised. A consensus approach was adopted to resolve any conflicting information yielded from different sources. All research interviews covered the following areas:

- Socio-demographic characteristics of subjects and proxy-informants: A structured questionnaire was used to record background information. This included age, gender, marital status, living arrangement, financial situation, education level, and occupation. The proxy- informants’ age, gender, occupation, and kinship with the subjects were also recorded.

- Subjects’ current and lifetime suicide profile: The number of lifetime suicide attempts and the circumstances surrounding the index attempt (perceived reasons, method used, timing, and place) were recorded. The level of intent of the index suicide attempt was assessed using the first 8 questions of Beck’s Suicidal Intent Scale (SIS).11 The SIS depicts the objective circumstances surrounding the attempt including the degree of planning, preparation, and precautions against being rescued. Higher scores indicate higher suicidal intent. The SIS has been shown to have satisfactory reliability and validity,12 has been translated into Chinese and used in a recent suicide research study in Hong Kong.13

- Physical health and health service utilisation: A standard checklist was used to record past and current major medical illnesses. In addition, subjects’ health service utilisation in the year prior to the suicide attempt was recorded in a structured questionnaire.

- Social network:

Social network was assessed for all subjects using the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS).14 The scale contains items assessing the level of actual contact, degree of interpersonal communication, and emotional support from family members or friends. Items are scored on a 5-point scale. The total LSNS score can range from 0 to 50; a high score indicates better social support. The reliability and validity of the scale were shown to be satisfactory when used in the Hong Kong Chinese population.15 - Psychiatric diagnoses:

Psychiatric diagnoses were established using the SCID Chinese-English bilingual version, validated in a Hong Kong Chinese population.16,17 The overall inter-rater reliability was 0.84 for the psychotic and mood disorder modules, and 0.71 for anxiety and stress-related disorder modules. Both current and lifetime diagnoses were assessed. - Life events:

The life-event checklist used in this study was modified from Paykel’s Life Event Scale.18 Our checklist contained major categories of stressful life events experienced by the subject in the past 3 years. These included family discord; passing away or serious health problems suffered by family members and friends; serious medical problems or injury inflicted on subjects; relational problems with spouse / family members / friends; changes in employment status and financial hardship; legal / litigation issues.

Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Windows version 11.5 was used for all data analyses. Apart from descriptive statistics, sensitivity and specificity of the psychiatric diagnoses endorsed by proxy-informants were calculated, using the subjects’ version as ‘gold standard’. The level of agreement between subjects and proxy-informants in all categorical variables was examined using kappa statistics. Alternatively, percentage of agreement was calculated when the kappa statistics was not applicable, i.e. there were asymmetric pairs in the cross-tabulation table for kappa statistics. Pearson or Spearman rank correlation was used to estimate the level of agreement in the continuous variables. Intraclass correlation coefficients were used in assessing the level of agreement in scale scores.

Level of agreement was categorised based on the benchmarks defined by Landis and Koch (poor < 0.01, slight 0.01-0.20, fair 0.21-0.40, moderate 0.41-0.60, substantial 0.61-0.80, almost perfect > 0.80).19

Results

During the study period, 108 individuals were referred for psychiatric assessment following a suicide attempt, of whom 71 agreed to participate in the study, giving a response rate of 66%. Regarding the 37 individuals (9 men and 28 women) who were not recruited, 27 were lost to follow-up after their discharge from hospital for the index suicide attempt, while 10 declined to participate. Reasons given by the latter included: “they did not want us to contact their relatives”, or “they did not have time”. The demographic and clinical profiles of these eligible but not enrolled subjects were as follows: mean age, 29 (SD, 10) years; ‘no psychiatric diagnosis’ (n = 22; 60%); adjustment disorder (n = 12; 32%); and MDD (n = 3; 8%). Drug overdose (n = 26) was over-represented among those not recruited, followed by superficial wrist laceration (n = 11).

Socio-demographic Profiles of Enrolled Subjects and Their Proxy-informants

Seventy one consecutive consenting subjects were enrolled; 26 (37%) men and 45 (63%) women, with a mean age of 35 (SD, 12) years. Only 6 (8%) of them lived alone. Seventy one proxy-informants were interviewed, of whom 39 were female; their mean age was 41 (SD, 12) years. The spouse / unmarried partner of the subjects accounted for 58% (n = 41) of the informants. Fifty two (73%) were residing with the subjects, whilst 62 (87%) claimed to be very familiar with them, and 60 (85%) claimed to have seen them a day before the index suicide attempt.

The most commonly used method of attempting suicide was drug overdose (n = 42, 59%). Other methods included wrist laceration (n = 14, 20%); jumping from a height (n = 14, 20%); charcoal burning (n = 8, 11%); and hanging (n = 1, 1%). The mean (SD) scores on the SIS endorsed by the subjects and proxy-informants were 6.1 (3.6) and 5.4 (3.5) respectively.

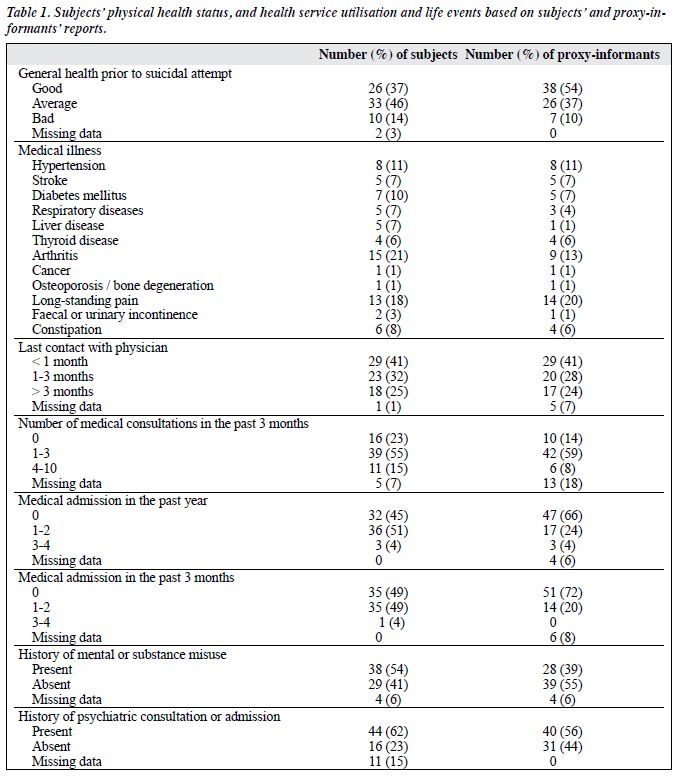

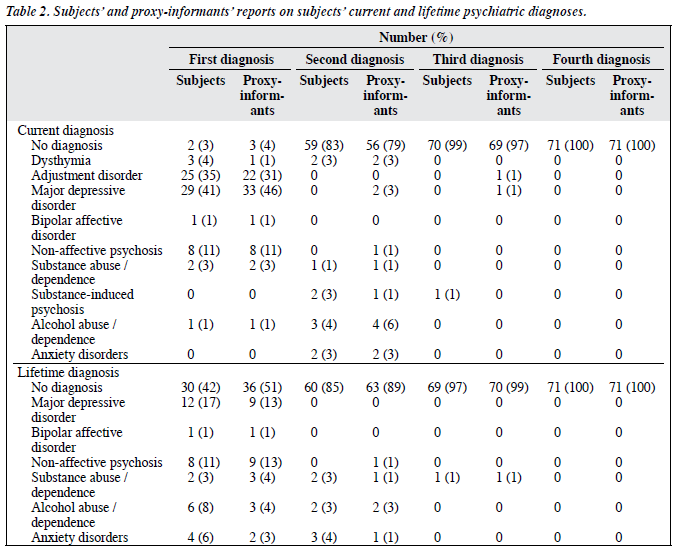

Table 1 summarises the physical health profile, health service utilisation, and life-events histories in the recent 3 years, based on the subjects’ or proxy-informants’ reports. Fifty nine (83%) claimed having average-to-good general health prior to the suicide attempt, in contrast to 64 (90%) of the proxy-informants who opined that subjects had average- to-good general health. Table 2 shows current and lifetime psychiatric diagnosis / diagnoses based on these reports.

Level of Agreement on Physical, Psychiatric, and Social Variables between Subject-proxy-informant Pairs

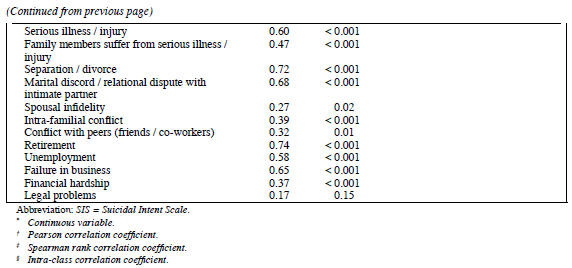

Table 3 summarises the level of agreement between subjects’ and proxy-informants’ reports on socio-demographic variables, current and lifetime suicide profiles, scores on SIS, social support, physical illness, health care utilisation, life events, and psychiatric diagnosis / diagnoses. By Landis and Koch’s definitions19 on the level of agreement, most domains reached moderate-to-substantial levels of agreement. Exceptions included a few socio-demographic variables, including: ‘importance of religion’ and ‘financial status’; some items on the SIS such as ‘timing of suicide attempt’ and ‘overt communication before the attempt’. Some physical illness items (subjective appraisal of general health; date of last medical consultation; and spousal infidelity / intra-familial conflicts / conflict with peers; legal problems) on the life-events checklist also yielded only fair levels of agreement.

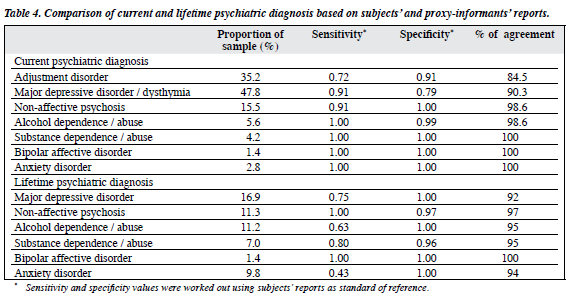

Table 4 summarises the sensitivity and specificity of psychiatric diagnosis / diagnoses endorsed by proxy- informants, using the subjects’ reports as reference.

Discussion

This study has to be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Since 34% of the eligible subjects were not recruited, there might be a selection bias towards recruiting more knowledgeable and cooperative informants, who gave more reliable information. The number of un-recruited potential subjects discharged from emergency room or general wards during non-office hours could not be accurately estimated. In terms of generalisability, suicide attempters presenting to our clinical setting might not be representative of other adult suicide attempters in the whole of Hong Kong, although there is no reason to suppose otherwise. By virtue of the heterogeneity in suicide attempters’ psychosocial variables, our study design and sample size did not permit evaluation of factors such as the proxy-informant’s characteristics and other circumstances surrounding the index suicide attempts to be evaluated.

Is the best-estimate methodology a valid means of assessing psychosocial risk factors and making psychiatric diagnosis in PA setting? This study shows that in a cohort of adult suicide attempters, the degree of agreement between subject and informant-endorsed information is ‘domain’- dependent:

- Despite substantial correlation between the total scores on the SIS endorsed by subjects and proxy-informants for the index attempt (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.75), subject-proxy concordance on individual items varied. High concordance was evident for the ‘presence of a suicide note’, fair-to-moderate concordance for items related to suicide planning, including ‘active preparation’, ‘final act’, ‘isolation’, ‘overt communication’, ‘timing’, ‘precautions’, and ‘help-seeking behaviour’. This implies that some high- risk suicide behavioural profiles (active planning and precaution against being rescued) eluded detection by knowledgeable informants. The subject-proxy discrepancy in these parameters may partly explain how subjects progressed through the suicide attempt. The subject-proxy concordance on the endorsement of current principal psychiatric diagnosis according to DSM-IV was substantial. Based on our analysis using subjects’ information as the standard, the sensitivity, specificity and percentage agreement were high across most current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. However, the sensitivity for detecting lifetime MDD by proxy-informants was relatively low (0.75). On the other hand, relatively low specificity (0.79) was observed in the current diagnosis of ‘MDD / dysthymia’. In technical terms, low specificity means low ‘true-negative rate’ (i.e. lower proportion of people without the disorder who are tested negative). That is to say, in common language, proxy-informants were more prone to endorse symptoms leading to more ‘MDD / dysthymia’ diagnoses in subjects who endorsed less ‘MDD / dysthymia’. This may be related to the bias of ‘searching for meaning’ for the suicide attempts on the part of the proxy-informants. From a cultural point of view, suicide is construed as a socially sanctioned means of protest and escape from interpersonal conflicts or other situations that may involve ‘loss of face’.20,21 ‘Medicalising’ a socially sanctioned behaviour, by ascribing a suicide attempt to a psychological illness, may be an honourable way out to alleviate the shame and guilt borne by family members.22 In line with this discussion, low sensitivity for detecting a past major depressive episode may be due to proxy-informants’ recall bias. Thus, past depressive episodes not associated with alarming behaviour (such as a suicide attempt) were not recognised. On the part of the subjects, however, the low specificity may stem from under-reporting of current ‘MDD / dysthymia’. It is believed that the Chinese tend not to endorse psychological sufferings and are more prone to articulate distress through somatic complaints.22 This is also in keeping with a past epidemiological survey in a Hong Kong Chinese population, in which the life-time prevalence of MDD was only 3.7%.8 Such a figure is much lower than the often-quoted 10 to 15% from western Epidemiological Catchment Area Studies.23

- In this study, proxy-informants could endorse subjects’ physical illness categories accurately, though they were inclined to over-value their perceived physical well-being. Physical well-being pertains to subjective self-appraisal and may not correlate well with objective physical impairment. Our observation shows that proxy-informants may be insensitive to subjects’ inner experiences. Such discrepancy in subject-proxy appraisal of general health may be a source of distress to suicide attempters. It may also constitute a distal or proximal risk factor for suicide, by way of lack of understanding of the subjective distress by people in their immediate social network. Such speculation is yet to be confirmed in a case-control study.

- Results concerning the levels of subject-proxy agreement on stressful life events were mixed. Proxy- informants tended to accurately endorse events such as ‘separation / divorce’, ‘marital discord’, ‘failure in business / bankruptcy’, ‘family members moving in / out’, ‘death of significant others’, ‘serious illness’, ‘changes in living condition’, ‘unemployment’, and ‘retirement’. These events were ‘externalising’ in nature and easily observed. Low levels of agreement were observed for items related to interpersonal conflicts. Possible explanations are that proxy- informants might have played an active part in such conflicts (e.g. with friends and family) and tended to under-report because of embarrassment. Alternatively, they might not want to attribute a subject’s suicide attempt as somebody else’s fault, in keeping with the traditional Confucian creed of ‘a gentleman and scholar should not gossip’. Also, such apparent lack of perception could be simply due to the proxy- informant’s lack of knowledge.

Can we apply our findings to examine the validity of PA? For obvious feasibility reasons, those who attempt suicide are the best available population with characteristics approximating to those whose suicide ‘succeeds’. A previous study has shown that completed suicides and medically serious suicide attempts entail two overlapping populations that share common psychiatric diagnostic and clinical features.24 By contrast, the aftermath of completed suicide is often more prolonged, socially complicated, and emotionally charged for informants. The time lag between the index completed suicide and the subsequent research interview is often up to 6-12 months in real-life PA, while in our study on suicide attempters, most informants and subjects were interviewed within 3 months of the index event. Such discrepancy might contribute to different degrees of time- dependent recall bias and emotional attributes pertaining to different stages of grief.

Other inherently different characteristics of proxy-informants in this study related to all our proxy-informants being nominated by the suicide attempters (as having the best / most appropriate knowledge about them). Whereas in PA studies of persons who become deceased, the informant was usually the legal next-of-kin or convenient best-available person, irrespective of their psychosocial relationship with the subject. Our study also excluded subjects who had no available informant. Thus we had a biased sample of subject-selected knowledgeable proxy- informants relative to those of other suicide deceased cohorts. Moreover, it is not uncommon for multiple informants to be involved in PA studies, whereas our investigation only recruited one informant per subject.

To conclude, our results support the validity of the best-estimate methodology for assessing psychosocial risk factors and making a psychiatric diagnosis for Hong Kong Chinese who attempt suicide.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Research Grant Council (CUHK-4373/03M), and this paper is adapted from Dr Edwin Pang’s Part III Dissertation for the Fellowship Examination of the Hong Kong College of Psychiatrists.

References

- World Health Report 2002. World Health Organization website: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/index.html.Accessed 1 Aug 2005.

- Schneidman ES, Farberow N. Sample investigation of equivocal suicide deaths. In: Farberow N, Schneidman ES, editors. The cry for help. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1961.

- Hawton K, Appleby L, Platt S, Foster T, Cooper J, Malmberg A, et al. The psychological autopsy approach to studying suicide: a review of methodological issues. J Affect Disord 1998;50:269-76.

- Conner KR, Conwell Y, Duberstein PR. The validity of proxy-based data in suicide research: a study of patients 50 years of age and older who attempted suicide. II. Life events, social support and suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:452-7.

- Heun R, Maier W, Muller H. Subject and informant variables affecting family history diagnoses of depression and dementia. Psychiatry Res 1997;71:175-80.

- Velting DM, Shaffer D, Gould MS, Garfinkel R, Fisher P, Davies M. Parent-victim agreement in adolescent suicide research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:1161-6.

- Chiu HF, Yip PS, Chi I, Chan S, Tsoh J, Kwan CW, et al. Elderly suicide in Hong Kong—a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004:109:299-305.

- Chen CN, Wong J, Lee N, Chan-Ho MW, Lau JT, Fung M. The Shatin community mental health survey in Hong Kong. II. Major findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993;50:125-33.

- Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, Bolhari J, Botega N, De Silva D, et al. Suicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE-MISS community survey. Psychol Med 2005;35:1457-65.

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL. Structured clinical interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders-Patient Edition-(SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996.

- 1 Beck RW, Morris JB, Beck AT. Cross-validation of the Suicidal Intent Scale. Psychol Rep 1974;34:445-6.

- Mieczkowski TA, Sweeney JA, Haas GL, Junker BW, Brown RP, Mann JJ. Factor composition of the Suicide Intent Scale. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1993;23:37-45.

- Tsoh J, Chiu HF, Duberstein PR, Chan SS, Chi I, Yip PS, et al. Attempted suicide in elderly Chinese persons: a multi-group, controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13:562-71.

- Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Community Health 1988;11:42-52.

- Chi I, Boey KW. A mental health and social support study of the old- old in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Department of Social Work and Social Administration, University of Hong Kong; 1994.

- So E, Kam I, Leung CM, Pang A, Lam L. The Chinese-bilingual SCID- I/P Project: Stage 2—Reliability for Anxiety Disorders, Adjustment Disorders, and ‘No Diagnosis’. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13:19-25.

- So E, Kam I, Leung CM, Chung D, Liu Z, Fong S. The Chinese bilingual SCID-I/P Project: Stage 1—Reliability for Mood Disorders and Schizophrenia. Hong Kong J Psychiatry 2003;13:7-18.

- Paykel ES, Prusoff BA, Uhlenhuth EH. Scaling of life events. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1971;25:340-7.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159-74.

- Ji J, Kleinman A, Becker AE. Suicide in contemporary China; a review of China’s distinctive suicide demographics in their sociocultural context. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2001;9:1-12.

- Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet 2002;360:1728-36.

- Lee S, Yu H, Wing Y, Chan C, Lee AM, Lee DT, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and illness experience of primary care patients with chronic fatigue in Hong Kong. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:380-4.

- Regier DA, Kaelber CT, Rae DS, Farmer ME, Knauper B, Kessler RC, et al. Limitations of diagnostic criteria and assessment of instruments for mental disorders. Implications for research and policy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:109-15.

- Beautrais AL. Suicides and serious suicide attempts: two populations or one? Psychol Med 2001;31:837-45.