East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2015;25:58-63

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dr Imon Paul, MBBS, MD, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, IQ City Medical College, Durgapur, West Bengal, India.

Prof. Vinod Kumar Sinha, MBBS, MD, DPM, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Kanke, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India.

Dr Sujit Sarkhel, MBBS, MD, DPM, Institute of Psychiatry, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (IPGMER), Kolkata, India.

Dr Samir Kumar Praharaj, MBBS, MD, DPM, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

Address for correspondence: Dr Samir Kumar Praharaj, Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka

576104, India.

Tel: (91) 8971026304; Email: samirpsyche@yahoo.co.in

Submitted: 7 July 2014; Accepted: 23 December 2014

Abstract

Objective: To assess the co-morbidity of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and other anxiety disorders in child and adolescent mood disorders.

Methods: A total of 100 patients aged < 18 years with mood disorders according to the DSM-IV-TR were screened for OCD and other anxiety disorders using Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version.

Results: The prevalence of co-morbid anxiety disorders was 22%; OCD was present in 4%, and subthreshold obsessive-compulsive symptoms were present in 2%. Among others, 8% had panic disorder, 7% had generalised anxiety disorder, 3% had separation anxiety disorder, and 1% had social phobia; multiple anxiety disorders were present in 3% of patients.

Conclusion: Co-morbid anxiety disorder was found in one-fifth of children and adolescents with mood disorder.

Key words: Anxiety disorders; Bipolar disorder; Child; Comorbidity; Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a chronic and distressing disorder that leads to significant impairment in academic, social, and family domains of functioning. It is often seen in children and adolescents: the lifetime prevalence of paediatric OCD ranges from 2% to 4%, with a 6-month prevalence of 0.5% to 1%.1 There is a high rate of psychiatric co-morbidities in childhood OCD; about 50% of those with childhood OCD have multiple co-morbidities and as many as 80% meet the diagnostic criteria of an additional Axis-1 disorder.2

Major depression is considered a common occurrence in patients with OCD. Several reports have described the high risk of (hypo)manic switches in juvenile OCD patients treated with tricyclics or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,3,4 implicating a bipolar diathesis in this population. Recent epidemiological studies suggest that co-morbidity between OCD and bipolar disorder (BD) is highly prevalent, with rates as high as 15% to 35%.5,6 Notwithstanding the emerging literature on co-morbidity between OCD and mood disorders, relatively few systematic data exist on the clinical characteristics of this interface and its treatment. Despite the potential clinical importance of this issue, it has not yet been properly explored. Data on mood disorder–OCD co-morbidity in the juvenile population are much scarce.7 A recent study to explore bidirectional co-morbidity between BD and OCD in youth and to examine the symptom profile and clinical correlates of these 2 disorders reported that a high rate of co-morbidity (21% of BD subjects and 15% of OCD subjects met DSM- III-R criteria for both disorders) and multiple anxiety disorders, especially generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and social phobia, were more often present when OCD and BD were co-morbid than otherwise.8 Similar studies in a juvenile population in India are lacking. Thus, the current study was undertaken to explore the co-morbidity of OCD and other anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with mood disorders.

Methods

Participants

This was a cross-sectional hospital-based study conducted at the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Unit of the Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, a tertiary referral centre in eastern India. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. The study sample comprised 100 consecutive patients of either gender, aged < 18 years, and diagnosed with mood disorders according to the DSM- IV-TR criteria.9 Those with co-morbid major medical or neurological illness or mental retardation were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the relatives.

Measures

A semi-structured specially designed proforma was used to collect socio-demographic and clinical details. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School- Age Children–Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS- PL),10 a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to assess current and past episodes of psychopathology in children and adolescents, was used to screen for co-morbid OCD and other anxiety disorders in patients with mood disorders. Diagnoses were scored as definite, probable (> 75% of symptom criteria met), or not present. A score of 2 indicated a subthreshold level of symptomatology, and a score of 3 represented threshold criteria. The clinician- rated Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)11 was used to assess the severity of obsessive- compulsive (OC) symptoms in those screened positive on K-SADS-PL. In addition, Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS),12 Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI),13 Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A),14 and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for Children (BPRS-C)15 were used to assess the associated psychopathology. All the assessments were carried out on admission by the first author prior to initiating pharmacotherapy.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago [IL], US). Patients were classified into anxiety group and non-anxiety group based on the presence of co-morbid anxiety disorder (including subthreshold anxiety symptoms) with mood disorder. Groups were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square test (with Yates continuity correction as required) and Mann-Whitney U test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Effect sizes were reported as phi (φ) coefficient and r (calculated from Z value of Mann-Whitney U test).16 An alpha level of < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

The mean (± standard deviation) age of study participants was 15.57 ± 1.75 years and 73% were male. Among them, 15% had unipolar depressive disorder and 85% had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The mean age of onset of mood disorder was 14.51 ± 2.53 years. In all, 77% of patients had acute or abrupt onset of illness and 40% had a family history of psychiatric illness. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in the study population was 22% (18% threshold and 4% subthreshold). Co-morbid OCD was present in 4%, and another 2% had subthreshold OC symptoms; the OC symptoms pre-dated the onset of mood disorder in all patients. The mean CY-BOCS total score was 22.00 ± 9.36. Among other anxiety disorders, 8% had panic disorder (6% threshold and 2% subthreshold), 7% had GAD (6% threshold and 1% subthreshold), 3% had separation anxiety disorder (SAD) [1% threshold and 2% subthreshold], and 1% had social phobia (threshold). One patient had SAD co-morbid with GAD, 1 patient had GAD co-morbid with OC symptoms, and 1 patient had SAD co-morbid with OC symptoms. Thus, multiple anxiety disorders were present in 3% of patients.

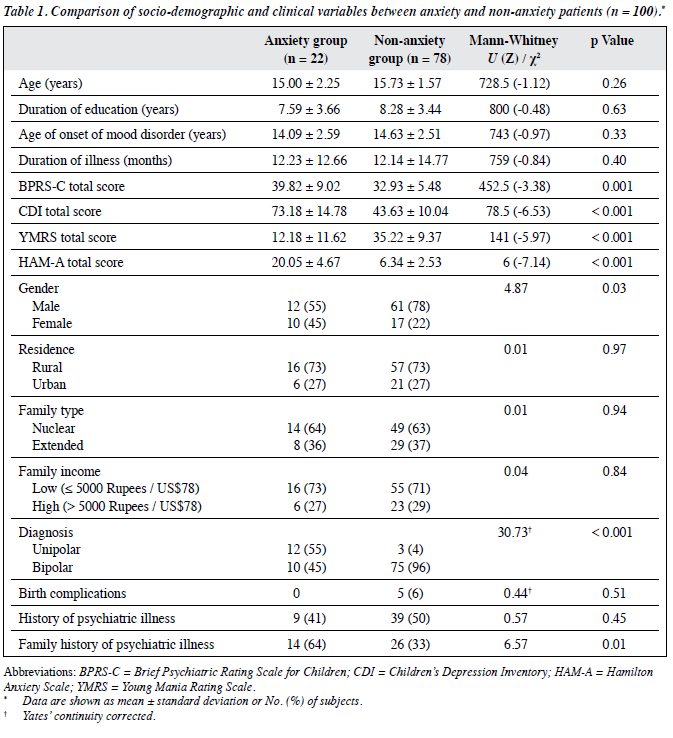

The group differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables between anxiety and non-anxiety patients are summarised in Table 1. There was a significantly higher proportion of females in the anxiety group (p = 0.03, φ = 0.22). The same group of patients also had a significantly higher proportion of a family history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.01, φ = 0.26) and unipolar depressive disorder was more common (p < 0.001, φ = 0.59) when compared with the non-anxiety group. There was no difference between the groups in age, education, age of onset of mood disorder, and illness duration. Significantly higher scores were found in the anxiety group for mean BPRS-C total score (p = 0.001, r = 0.34), CDI total score (p < 0.001, r = 0.65) and HAM-A total score (p < 0.001, r = 0.71), whereas mean YMRS total score (p < 0.001, r = 0.59) was higher in the non-anxiety group.

All patients with OCD had a family history of psychiatric illness (p = 0.01, φ = 0.31). In those with OCD, 4 (66.7%) had unipolar disorder and 2 (33.3%) had bipolar disorder (p = 0.002, φ = 0.37). The mean CDI total score was significantly higher in those with OCD (p = 0.01, r = 0.28), whereas the mean YMRS total score was lower than those without OCD (p = 0.001, r = 0.33).

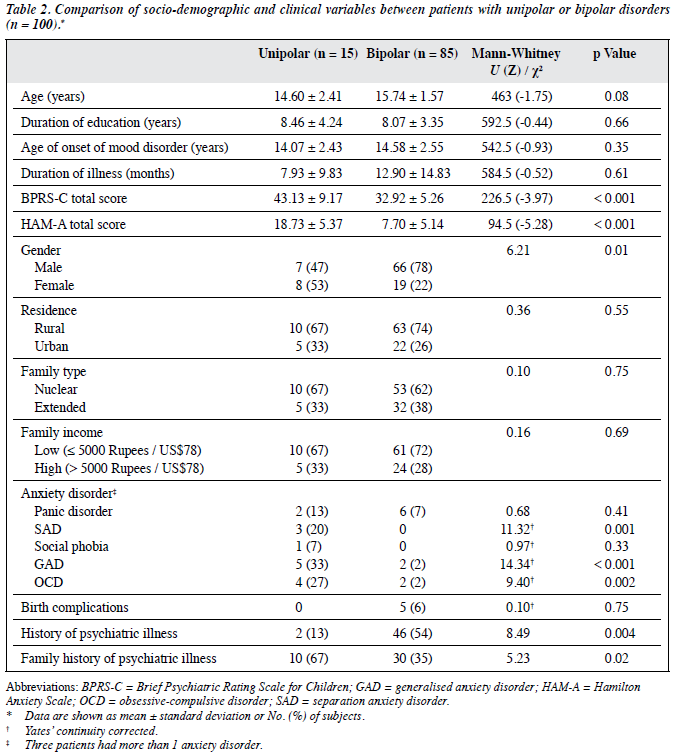

The group differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables between unipolar and bipolar patients are summarised in Table 2. There was a significantly higher proportion of females in the unipolar group compared with the bipolar group (p = 0.01, φ = 0.25). A significantly higher proportion with a family history of psychiatric illness was also noted in the unipolar group (p = 0.02, φ = 0.23) whereas a history of psychiatric illness was more common in the bipolar group (p = 0.004, φ = 0.29). A significantly higher proportion of unipolar patients had SAD (p = 0.001, φ = 0.42), GAD (p < 0.001, φ = 0.43) and OCD (p = 0.002, φ = 0.36) compared with those with bipolar disorder. Unipolar patients also had a significantly higher mean BPRS-C total score (p < 0.001, r = 0.39) and HAM-A total score (p < 0.001, r = 0.52) than bipolar patients.

Discussion

The prevalence of anxiety disorders among children and adolescents with mood disorder was 22% in our study (18% threshold and 4% subthreshold), which is relatively lower than previous reported rates of 25% to 50%.17 There were higher rates of SAD, GAD, and OCD in patients with unipolar disorder compared with bipolar patients. In our sample, the higher percentage of bipolar disorder (85%) could explain the lower rates of co-morbid anxiety disorders. In addition, bipolar I disorder and pure mania, which predominated in our sample, have been reported to inhibit expression of panic and other anxiety disorders.18,19

The reason for high co-morbidity of anxiety and mood disorders has been attributed to some common genetic factors or influences. A tripartite model has also been proposed which posits that anxiety and depression share a common component of negative affect.20

Co-morbid OCD was present in 4%, and 2% had subthreshold OC symptoms. Among other anxiety disorders, 8% had panic disorder, 7% had GAD, 3% had SAD, and 1% had social phobia. The prevalence of OCD in children and adolescents with BD varied from 0% to 54% across studies.21 It has also been reported by Pashinian et al22 that the rate of co-morbid OCD in bipolar patients who experience a first manic episode (DSM-IV criteria) does not differ significantly to the prevalence of OCD in the general population (1.8% vs. 1.5%-2.3%). This supports the lower rates of OCD found in our study as our study population consisted of a high percentage of first-episode mania patients.

Multiple anxiety disorders were found in 3 patients, of whom 2 had co-morbid OC symptoms. This finding is similar to that of Joshi et al8 who found significantly higher rates of multiple anxiety disorder in those with OCD bipolar co-morbidity than in those without co-morbidity. Thus, our study further emphasises that children and adolescents with OC bipolar co-morbidity are at a higher risk of lifetime multiple anxiety disorders.

The proportion of females was greater in those with co-morbid anxiety disorder in our study, although the effect size was small. This is consistent with the study by Yerevanian et al23 that examined anxiety disorder co-morbidity in mood disorder subgroups in an adult population. Patients with co-morbid anxiety disorder also had higher rates of family history of psychiatric illness, similar to the findings of Dilsaver et al,24 albeit with small effect size. In addition, unipolar depressive disorder was overrepresented in those with co-morbid anxiety disorder, and the effect size for the association was high. Previous studies have reported anxiety disorders in 20% to 75% of children and adolescents with depression.25,26

In our study, the severity of psychotic and depressive symptoms was higher in patients with co-morbid anxiety disorder, whereas the severity of manic symptoms was higher in patients without co-morbid anxiety disorder. Patients with affective disorder with anxiety had less manic symptoms, and more symptoms of depression and anxiety. These findings are again expected as pure mania has been reported to inhibit panic and other anxiety disorders.18,19

Consistent with earlier studies, in our study OCD symptoms pre-dated the onset of mood disorder in all patients with co-morbid OCD, thus supporting the hypothesis of a first internalising phase in early-onset bipolar disorder.7 All patients with OCD had a family history of psychiatric illness with medium effect size. Also, higher rates of OCD were found in patients with unipolar disorder compared with bipolar disorder, with medium effect size.

Our study suggests that co-morbid anxiety disorders are frequent in childhood mood disorder. Specifically, higher rates of anxiety disorders are observed with unipolar disorder compared with bipolar patients, similar to the adult population. The presence of co-morbid anxiety disorders indicates a higher severity of mood disorders that implies the need for identification and early treatment of this subgroup of patients.

The current study have some limitations. First, it was hospital-based, thus unipolar and bipolar II disorder were underrepresented. Second, selection of patients with severe illness limited generalisation of findings to the community. Third, the rating scales used in our study were not validated for our population. Finally, as it was a cross-sectional study, prognostic indicators could not be identified. Further prospective studies are required to clarify the relationship and the developmental trajectory of anxiety and mood disorders in children.

References

- Piacentini J, Bergman RL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2000;23:519-33.

- Hollander E, DeCaria C, Gully R, Nitescu A, Suckow RF, Gorman JM, et al. Effects of chronic fluoxetine treatment on behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res 1991;36:1-17.

- Go FS, Malley EE, Birmaher B, Rosenberg DR. Manic behaviors associated with fluoxetine in three 12- to 18-year-olds with obsessive- compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1998;8:73-80.

- Diler RS, Avci A. SSRI-induced mania in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:6-7.

- Krüger S, Cooke RG, Hasey GM, Jorna T, Persad E. Comorbidity of obsessive compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 1995;34:117-20.

- Perugi G, Akiskal HS, Pfanner C, Presta S, Gemignani A, Milanfranchi A, et al. The clinical impact of bipolar and unipolar affective comorbidity on obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord 1997;46:15-23.

- Masi G, Perugi G, Toni C, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, et al. Obsessive-compulsive bipolar comorbidity: focus on children and adolescents. J Affect Disord 2004;78:175-83.

- Joshi G, Wozniak J, Petty C, Vivas F, Yorks D, Biederman J, et al. Clinical characteristics of comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord 2010;12:185-95.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School- Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:980-8.

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:844-52.

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry 1978;133:429-35.

- Kovacs M. Children Depression Inventory (CDI): manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1992.

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959;32:50-5.

- Overall JE, Pfefferbaum B. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for children. Psychopharmacol Bull 1982;18:10-6.

- Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991.

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depress Anxiety 2001;14:67- 78.

- Dilsaver SC, Chen YW, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Tsai-Dilsaver Y, Krajewski KJ. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-mania. Psychiatry Res 1997;73:47-56.

- Dilsaver SC, Chen YW. Social phobia, panic disorder and suicidality in subjects with pure and depressive mania. J Affect Disord 2003;77:173- 7.

- Anderson ER, Hope DA. A review of the tripartite model for understanding the link between anxiety and depression in youth. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:275-87.

- Jana AK, Praharaj SK, Sinha VK. Comorbid bipolar affective disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder in childhood: a case study and brief review. Indian J Psychol Med 2012;34:279-82.

- Pashinian A, Faragian S, Levi A, Yeghiyan M, Gasparyan K, Weizman R, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar disorder patients with first manic episode. J Affect Disord 2006;94:151-6.

- Yerevanian BI, Koek RJ, Ramdev S. Anxiety disorders comorbidity in mood disorder subgroups: data from a mood disorders clinic. J Affect Disord 2001;67:167-73.

- Dilsaver S, Akiskal H, Akiskal K, Benazzi F. Dose-response relationship between number of comorbid anxiety disorders in adolescent bipolar / unipolar disorders, and psychosis, suicidality, substance abuse and familiarity. J Affect Disord 2006;96:249-58.

- Kovacs M, Devlin B. Internalizing disorders in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998;39:47-63.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999;40:57-87.