East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2022;32:34-8 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2128

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

D Poremski, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

YM Mok, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

GFK Lam, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

R Dev, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

HC Chua, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

DSS Fung, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore

Address for correspondence: D Poremski, Institute of Mental Health, Singapore.

Email: Daniel.poremski@mail.mcgill.ca

Submitted: 27 April 2021; Accepted: 14 March 2022

Abstract

Objectives: To compare the incidence of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) between inpatients at the Institute of Mental Health in Singapore and the general population over 8 years to determine the effectiveness of our infection control strategies.

Methods: Data for cases of influenza and URTI at our institute between January 2012 and December 2019 were collected. National data were derived from weekly infectious disease bulletins that report daily averages of people attending polyclinics/surgeries with influenza and URTI. Interrupted time series analyses were used to determine the impact of infection prevention and control strategies on incidence.

Results: Over the 8 years, there were 1607 cases of URTI involving 182 clusters, equal to 3.16 cases per 10 000 patient-bed-days. 965 (60%) cases and 95 (52%) clusters occurred in long-stay wards, whereas 642 (40%) cases and 87 (48%) clusters occurred in acute wards. The median cluster size was 12 in the long-stay wards and 7 in the acute wards (p<0.0001). The spikes in cases in June and December may be attributed to the increased staff and visitor mobility during school vacations in June and December. Strategies implemented during the study period did not significantly reduce the incidence of URTI. Previous strategies implemented in 2005 to meet accreditation standards are more likely to be contributors.

Conclusion: Infection control strategies of our institute appear to be effective, because the incidence of URTI was lower in our institute than in the community. The similar incidence of URTI in acute and long-stay wards indicates that service-user turnover is not a contributor. Rather, staff and visitors are more likely to be the vector. The larger clusters in long-stay wards indicates a greater risk of transmission in such settings. Increased activity in our institute during school vacations may be associated with an increase in cases in June and December. It is difficult to determine if strategies implemented during the study period successfully reduce the incidence of URTI.

Key words: Hospitals, psychiatric; Public health surveillance; Respiratory tract infections

Background

Infection prevention and control is important in institutionalised settings. In locations where people spend prolonged time with each other, especially when contact cannot easily be limited, infections may spread quickly once introduced from an external source.10,13,17 Institutionalised facilities may benefit from stringent infection prevention and control protocols that prevent introduction and transmission of external contagions,1,2,5 with guidelines and recommendations widely reported.4,7,8,14,18 These guidelines balance the risk of infection with the freedom of services. Because the balance is slightly skewed toward freedom, low-risk-infections are tolerated as an eventuality. However, the balance shifts toward more stringent protocols during pandemics. Infection control units implemented in Swiss psychiatric hospitals,1 French psychiatric hospitals,6 and Japanese psychiatric hospitals19 have successfully detected and contained the spread of influenza and upper respiratory tract infections within psychiatric units. We aimed to compare the incidence of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) between inpatients of the Institute of Mental Health in Singapore and the general population over 8 years to determine the effectiveness of our infection control strategies.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the Institute of Mental Health (reference: 727-2020) and Singapore (reference: 2020/00801). Data for cases of influenza and URTI at our institute between January 2012 and December 2019 were collected. National data were derived from weekly infectious disease bulletins3 that report daily averages of people attending polyclinics/surgeries with influenza and URTI.

In Singapore, tertiary mental health services are predominantly provided by our institute. In 2005, our institute obtained Joint Commission International accreditation12 and has maintained it since. Our institute employs around 2500 staff and has a capacity of approximately 2000 inpatient beds, accounting for 90% of Singapore’s total psychiatric beds. Half of the capacity are for long-stay (>12 months) care, and half are for acute and rehabilitation services. Length of stay ranges from 11 to 16 days in acute wards and as long as necessary (usually 3 months) for rehabilitation services. The bed occupancy rate is around 89%, which is approximately 51 000 patient-bed-days per month. Each year, our institute receives around 16 000 emergency service visits,11 36 000 outpatient visits, and approximately 20 000 family visitors.

Since January 2012, the infection control department has recorded all detected cases of URTI. Data recorded included date of detection, date of resolution, date of admission, age, temperature (if febrile) at time of detection, prescribed treatment, and vaccination status. A timeline was formed to correspond with the institute’s monthly bed occupancy rate. Yearly reports of causes of death at the institute were reviewed to determine the prevalence of URTI-related deaths. Diagnosis of URTI was made by clinical examination and assessment of symptoms. Virus strains were identified through the polymerase chain reaction method on swabs. A cluster was defined as ≥3 cases occurring within the ward over a duration set according to the period of incubation and recovery of the detected pathogen. Strain results were sent to the Ministry of Health for comparison with those in the community.

Monthly incidence of infectious diseases in the inpatient population was compared with that in the Singapore population, which includes foreign workers, permanent residents, and citizens.20 Monthly population data were estimated by plotting a growth curve of yearly data from January 2012 to December 2019. Lowess smoothing and local polynomial smoothing functions were used to present the length of illness and the number of cases over time, respectively. Single-group interrupted time series analysis was used to determine the impact of the implemented strategies on the incidence. Non-parametric K-sample test was used to determine if the cluster size and length of illness differed between acute and long-stay wards. Analyses were conducted in Stata 16 with the interrupted time series analysis command.9

According to the guiding principles of the infection control strategies, both service users and staff should be equally considered to ensure uncompromised care. In mental health services, care should be provided with the least restrictive means,15 which may be set aside according to the nation’s infection control strategies. Constant assessment of the risks and effectiveness of current strategies is needed to strike a balance. Thus, a disease outbreak task force meets regularly to discuss developments in infection control strategies and the risks of hospital-acquired infection and introduced infections.

Strategies implemented for accreditation and for compliance with health ministry include: (1) yearly audits of staff proficiency with personal protective equipment (since 2004), (2) monthly audits of hand hygiene techniques16 (since 2005), (3) subsidised influenza vaccination for service users (since May 2004), (4) yearly infection control risk assessments and reviews (since 2008), (5) introduction of patient education on hygiene and sanitation7 (since 2008), (6) placement of liquid antiseptic dispensers at each ward exit throughout consultation/treatment, restrooms, and common areas of the administrative buildings (since 2008), (7) provision of portable alcohol hand rub dispensers to all healthcare workers to facilitate point of care usage to improve hand hygiene compliance(since 2008), (8) bimonthly audits of infectious waste disposal procedures (since 2008), (9) introduction of after-action reviews to learn from incidents and produce recommendations (since 2008), (10) mandatory food hygiene certification for staff handling food (since 2011), (11) vaccinations for patients against pneumococcal variants (in 2013 and 2008), (12) weekly and routine audits of proper decontamination of reusable patient’s equipment/items (since 2014), (13) biyearly review of institutional policies toward the use of antibiotics (since 2015), (14) biyearly reassessment of disaster preparedness plans and yearly pandemic exercise (since 2017), (15) tracking of staff immunisation status (since 2017), (16) monthly audits of beds cleaning and environmental cleaning (since 2017), and (17) rotating monthly audits of hospital- wide infection prevention and control practices in 2-year cycles (since 2018). These audits are performed by trained infection control nurses and physicians in accordance with the Joint Commission International reaccreditation in July 2011, May 2014, and June 2017.

Results

Over the 8 years, the Institute of Mental Health served 5 072 135 patient-bed-days. There were 1607 cases of URTI involving 182 clusters, equal to 3.16 cases per 10 000 patient- bed-days. The mean patient age was 54.6 ± 14.3 years. Psychiatric diagnoses of 501 cases were recorded, with psychosis-related problems being most common (73%), followed by mood-related problems (16%) and intellectual disability (11%), similar to the composition of the inpatient population.

Of the 1607 cases, 574 (35.7%) occurred in female wards, 927 (57.7%) in male wards, and 106 (6.6%) in mixed wards. 965 (60%) cases and 95 (52%) clusters occurred in long-stay wards, whereas 642 (40%) cases and 87 (48%) clusters occurred in acute wards. The median cluster size was 12 (interquartile range [IQR] = 8-16) in the long-stay wards and 7 (IQR = 5-11) in the acute wards (p<0.0001), involving a median of 9 (IQR = 6-14) service users and a median of 3 (IQR = 2-6) staff. The clusters affected 524 staff. 25 (13.7%) clusters involved exclusively service users. No deaths were recorded in the dataset, but three pneumonia-related deaths with symptoms of URTI were reported by independent records of deaths at the institute or shortly after transfer to general hospitals.

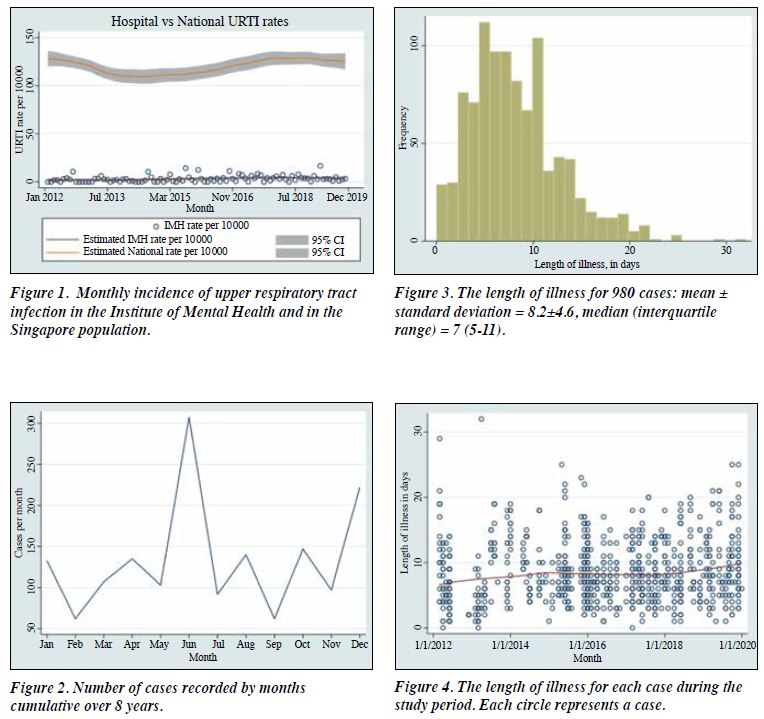

Comparing the monthly incidence of URTI between the inpatients and the Singapore population, the most relevant infection control strategies over the study period were periodic audits of decontamination practices (in 2014 and 2017). However, these were not associated with changes in incidence of URTI in 2014 (β = 0.19, p = 0.489, 90% CI = -0.35 to 0.74) and in 2017 (β = -0.25, p = 0.387, 90% CI = -0.81 to 0.32) [Figure 1]. The spikes in cases in June and December (Figure 2) may be attributed to the spikes in community cases habitually occur in early May and November (data not shown). The spikes also corresponded with the pedagogical seasons, with increased volunteer, visitor, service user, and staff mobility during school vacations in June and December.

Of the 1607 cases, 627 had missing data on the date of resolution. In the remaining 980 cases, the median length of illness (a metric for recommendation of the length of isolation) was 7 days (IQR = 5-11) [Figure 3]. The length of illness steadily increased with time (Figure 4) and did not differ between acute and long-stay wards (p = 0.789). Of the 1607 cases, 845 had temperature taken. 282 of these were afebrile and the remaining 563 had a mean temperature of 37.6 ± 1.78 at the time of diagnosis. Of the 1607 cases, 1049 had flu vaccination status recorded. Of these, 758 were vaccinated for the year, 290 were not, and one refused flu vaccination. Of the 1607 cases, 288 had pneumococcal vaccination status recorded. Of these, 97 were vaccinated and 191 were not. Of the 524 staff linked to the clusters, 513 had flu vaccination, whereas staff pneumococcal vaccination data were not known.

Discussion

Infection control strategies are important in institutional settings.1,6 In the present study, the number of clusters was equally divided between acute wards and long-stay wards. This implies that pathogens are introduced by staff or visitors and that spikes in cases follow the population trends. We would have expected that the incidence of URTI would be higher in acute wards than long-stay wards because of greater service user turnover of acute wards and greater isolation of long-stay wards. However, cases in acute wards may have experienced isolation within the community prior to admission and thus were at lower risk of acquiring URTI before admission. The length of stay was not associated with the risk of URTI.

Clusters in the long-stay wards accounted for 60% of influenza cases and were significantly larger than those in acute wards. This suggests that pathogens are more frequently transmitted between service users in long-stay wards. The increased transmissivity may be due to the nature of the long-stay wards, which fosters familiarity and greater interpersonal contact, whereas service users in acute wards may maintain a greater social distance. Ward managers may help reduce the cluster size by ensuring social distancing in wards and isolation of index cases.

The median length of illness over the study period was 7 days, which is in line with the norm but longer than the 3.7 days reported in a previous study.6 Hospital-specific and infection-specific data of pathogens are important in implementation of isolation protocols. Data to determine the time elapsed between detection and onset of symptoms were not available. It may be desirable for policymakers and infection control departments to monitor detection lag.

No single infection control strategy was associated with a significant reduction of infection cases. It is difficult to assess impact of individual strategies owing to their cumulative effect. The rate of infection in our institute was consistently lower than that in the community. This suggests that infection control strategies of our institute are effective in controlling the introduction and spread of influenza.

There are limitations to the present study. Data from other hospitals in Singapore were not used for comparison. People visiting private healthcare providers for URTI were not counted, which might discount the incidence of URTI in the general population. In addition, data for infection control did not include psychiatric diagnosis data. Symptom- based diagnoses (rather than laboratory-based diagnoses) were made. This may over-estimate the cases of URTI, although such over-estimation is in accordance with our institute’s protocol of treating all suspected cases with the same precaution. Furthermore, the study period from 2012 to 2019 could not assess the impact of previous infection control strategies such as those implemented to meet accreditation standards in 2005. As a result, the infection control strategies implemented during the study period may have little extra impact on infection control. Previous strategies are more likely to contribute to the difference in rates of infection between community and our institute.

Conclusion

Infection control strategies of our institute appear to be effective, because the incidence of URTI was lower in our institute than in the community. The similar incidence of URTI in acute and long-stay wards indicates that service- user turnover is not a contributor. Rather staff and visitors are more likely the vector. The larger clusters in long- stay wards indicates a greater risk of transmission in such settings. Increased activity in our institute during school vacations may be associated with an increase in cases in June and December. It is difficult to determine if strategies implemented during the study period successfully reduce the incidence of URTI.

Contributors

DF designed the study. DP and GLFK acquired the data and analysed the data. DP, RD, MYM, CHC, and DF drafted the manuscript. GLFK, RD, CHC, and DF critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the Institute of Mental Health (reference: 727-2020) and Singapore (reference: 2020/00801). The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures and for publication.

References

- Büchler AC, Sommerstein R, Dangel M, Tschudin-Sutter S, Vogel M, Widmer AF. Impact of an infection control service in a university psychiatric hospital: significantly lowering healthcare-associated infections during 18 years of surveillance. J Hosp Infect 2020;106:343-7. Crossref

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection control in healthcare personnel: infrastructure and routine practices for occupational infection prevention and control services. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/healthcare- personnel/index.html

- Communicable Diseases Division. Weekly infectious disease bulletin. Singapore: Ministry of Health. Available from: http://www.moh.gov. sg/content/moh_web/home/statistics/infectiousDiseasesStatistics/ weekly_infectiousdiseasesbulletin.html.

- Fukuta Y, Muder RR. Infections in psychiatric facilities, with an emphasis on outbreaks. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013;34:80-8. Crossref

- Garner JS. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996;17:54-80. Crossref

- Gaspard P, Mosnier A, Gunther D, et al. Influenza outbreaks management in a French psychiatric hospital from 2004 to 2012. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014;36:46-52. Crossref

- Gilbride SJ, Lee BE, Taylor GD, Forgie SE. Successful containment of a norovirus outbreak in an acute adult psychiatric area. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:289-91. Crossref

- Li PH, Wang SY, Tan JY, Lee LH, Yang CI. Infection preventionists’ challenges in psychiatric clinical settings. Am J Infect Control 2019;47:123-7. Crossref

- Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single-and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J 2015;15:480-500. Crossref

- McMichael TM, Currie DW, Clark S, et al. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2005-11. Crossref

- Poremski D, Kunjithapatham G, Koh D, Lim XY, Alexander M, Lee C. Lost keys: understanding service providers’ impressions of frequent visitors to psychiatric emergency services in Singapore. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:390-5. Crossref

- Poremski D, Lim ISH, Wei X, Fang T. The perspective of key stakeholders on the impact of reaccreditation in a large national mental health institute. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2020;46:699-705. Crossref

- Richtel M. Nursing homes are starkly vulnerable to coronavirus. The New York Times. Available from: https://nyti.ms/2Ig3pr0

- Sehulster LM, Chinn RYW, Arduino MJ, et al. Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/index.html

- Semple D, Smyth R. Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013 Crossref

- Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ, Gergen-Teague MF, Sobsey MD, Samsa GP, Rutala WA. Comparative efficacy of hand hygiene agents in the reduction of bacteria and viruses. Am J Infect Control 2005;33:67-77. Crossref

- Su S, Wong G, Shi W, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol 2016;24:490-502Crossref

- Weber DJ, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Vinjé J, Brown VM, MacFarquhar JK, Engel JP, Rutala WA. Lessons learned from a norovirus outbreak in a locked pediatric inpatient psychiatric unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26:841-3. Crossref

- Yamazaki Y, Goto N, Iwanami N, et al. Outbreaks of influenza B infection and pneumococcal pneumonia at a mental health facility in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2017;23:837-40. Crossref

- Yearbook of Statistics Singapore. Republic of Singapore: Ministry of Trade & Industry. 2019