East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2022;32:11-6 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2138

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sifat E Syed, Department of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Mohammad Khan, National Institute of Mental Health, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Helal Uddin Ahmed, National Institute of Mental Health, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Address for correspondence: Sifat E Syed, Department of Psychiatry, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Email: sifat.syed@yahoo.com

Submitted: 28 May 2021; Accepted: 10 February 2022

Abstract

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental health of children, adolescents, and their parents. This study aimed to assess the emotional and behavioural changes in children and adolescents and their association with parental depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh.

Methods: On 7 May 2020 during COVID-19 lockdown, an online questionnaire was distributed through social media and made available for 10 days. Data were collected from parents of children aged 4 to 17 years. The Bangla version of the parent-rated version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to determine the behavioural and emotional disturbances of the children and adolescents. The Bangla version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to assess the depression status of parents.

Results: There were 512 participants. 21.5% of children and adolescents had emotional and behavioural problems. More boys than girls had abnormal peer relationship problems (21.1% vs 15.4%, p = 0.03). Of the parents, 16.2% had moderate depression, 5.5% moderately severe depression, and 2.9% severe depression. 8.2% and 2.9% of parents reported that it was very difficult and extremely difficult, respectively, to do work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people; the proportion was higher in mothers than fathers (χ2 = 11.4, df = 3, p = 0.01). The PHQ-9 total score of parents mildly correlated with the SDQ score of children and adolescents (r = 0.51, p = 0.01). In multiple linear regression, a combination of parent sex (β = 0.08, p < 0.001), child’s history of developmental/psychiatric problems (β = 0.02, p = 0.67), and the SDQ total score of children and adolescents (β = 0.52, p = 0.03) accounted for 27% of the variability in PHQ total score of parents.

Conclusion: During lockdown, the prevalence of psychiatric disorder among children and adolescents and their parents increased. The depression status of parents mildly correlated with the behavioural and emotional disturbances of children and adolescents. We recommend opening the schools as soon as the situation improves and developing interventions such as virtual mental health assessment for children and adolescents and their parents.

Key words: Adolescent; Bangladesh; Children; COVID-19; Depression; Parents

Introduction

COVID-19 is a highly contagious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus: SARS-CoV-2. In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic. Isolation, contact restrictions, and economic shutdown affect the psychosocial environment of children, adolescents, and their families profoundly. Schools are closed, social contacts limited, and out-of-home leisure time activities cancelled. Parents need to support their children with home schooling while working from home. In April 2020, schools were closed in 188 countries, and 90% of the school-going population were affected. Prolonged school closure results in disruption in routine, boredom, and lack of innovative ideas among children and adolescents.1 The rising levels of unemployment put a lot of pressure on children, adolescents, and their families and result in distress, mental health problems, and violence.2 Nonetheless, mental health status in children and adolescents may be neglected because their incidence of infection and mortality is lower than that in adults.3

In a study in Shaanxi, China during February 2020, the most common psychological and behavioural problems among children and adolescents were clinginess, distraction, irritability, and fear of asking questions about the pandemic.4 Both parents and children were substantially affected by the pandemic. Parent-reported daily negative mood increased significantly during the pandemic; >25% of parents reported worsening of mental health and 14.3% of parents reported worsening behavioural health of their children.5 The amount of time spent in front of screens for education, entertainment, and social interaction increased among children and adolescents.6 However, the presence of electronic entertainment is associated with depression and anxiety.7 Children with special needs might miss their chance to develop essential social skills owing to closure of special schools, speech therapy sessions, and social skills groups.1

Bangladesh is a lower-middle-income country, with 40% of the population under the age of 18 years. From 17 March 2020, Schools were closed and all public examinations were cancelled. During lockdown, the prevalence of predictive psychiatric disorders was 39.7% among children and adolescents in Bangladesh.8 19.3% of them had moderate mental health disturbances and 7.2% had severe disturbances.9 The present study aimed to assess the emotional and behavioural changes in children and adolescents and their association with parental depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh.

Methods

This web-based cross-sectional survey used a non-probability sampling method. The sample size was determined by the formula: n=Z2pq/d2. Using p = prevalence of psychiatric disorder in children and adolescents, which was 18%,10 the expected sample size was 226. During lockdown, face-to- face interview or randomisation was not possible. Thus, the final sample size increased to 512.

On 7 May 2020, the questionnaire in Google form was distributed through social media (Facebook, Whatsapp, Messenger, Viber) and available for 10 days. Data were collected from the parents (either father or mother) who had children aged 4 to 17 years. Parents with more than one child were asked to fill up the form for the youngest child. The form contained four parts: consent, sociodemographic and COVID-19-related questions, the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The parents were also asked whether the child had been diagnosed with neurological/developmental/ psychiatric disorder (such as epilepsy, autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), whether their home was under red zone (presence of COVID positive patients), and whether they knew anyone infected with or died from COVID-19.

The Bangla version of the parent-rated version of the SDQ11 was used to determine the behavioural and emotional disturbances of the children and adolescents. It is a screening tool with 25 positive or negative attributes. Scores are generated for conduct problems, hyperactivity- inattention, emotional symptoms, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour; all except for prosocial behaviour are summed to generate a total difficulties score.

The PHQ-9 has been used for screening depression in community settings, with 88% sensitivity and 88% specificity.12 The Bangla version of the PHQ-913 was used to assess the depression status of parents. It consists of nine items measured on a 4-point Likert scale. Standard cut-off scores for depression symptoms are used: 0 (no depression), 1-4 (minimal), 5-9 (mild), 10-14 (moderate), 15-19 (moderately severe), and 20-27 (severe). In addition, parents were asked how difficult these depressive symptoms had made it to do work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people.

Data analysis was performed using the SPSS (Windows version 23; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). Descriptive statistics were used to determine associations between variables. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 512 parents aged 23 to 58 (mean, 38.4±5.5) years, 293 (57.2%) were mothers and 219 (42.8%) were fathers. Of their children and adolescents aged 4 to 17 (mean, 8.6±3.6) years, 258 (50.4%) were boys and 254 (49.6%) were girls. 367 (71.7%) were aged 4 to 10 years and 145 (28.3%) were aged 11 to 17 years.

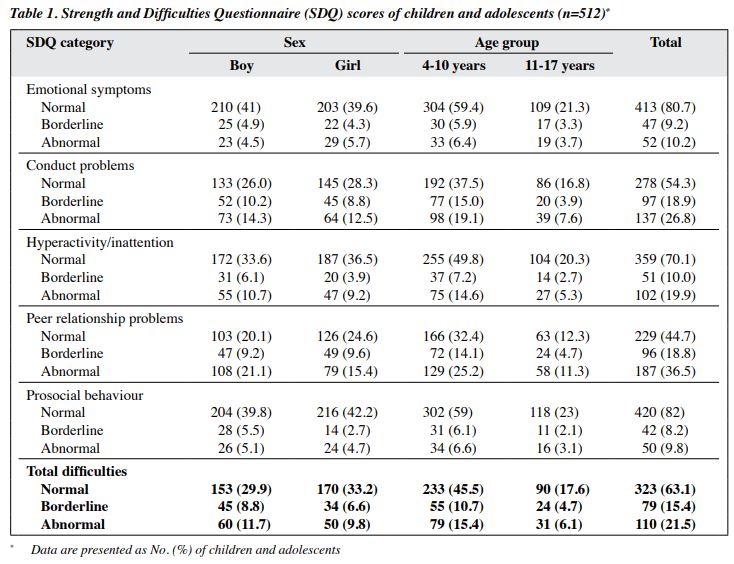

History of mental/developmental disorder was reported in 41 (8%) children and adolescents. 175 (34.2%) participants were from houses in the red zone; 43 (8.4%) knew someone who was COVID-positive; of 43 participants, 10 (23.3%) knew someone who died from COVID-19. 21.5% of children and adolescents had emotional and behavioural problems (abnormal SDQ total score). The prevalences of emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems were 10.2%, 26.8%, 19.9%, and 36.5%, respectively. All SDQ categories were similar between boys and girls and between children and adolescents, except that more boys than girls had abnormal peer relationship problems (21.1% vs 15.4%, p = 0.03, Table 1).

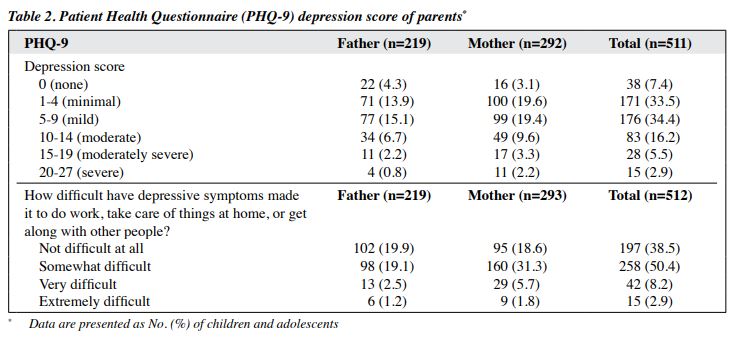

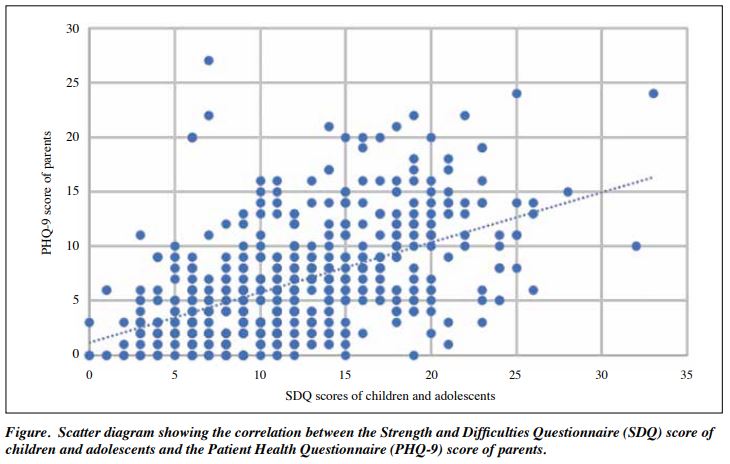

Of the parents, 16.2% had moderate depression, 5.5% moderately severe depression, and 2.9% severe depression. More mothers than fathers had depression, but the difference was not significant (Table 2). 8.2% and 2.9% of parents reported that it was very difficult and extremely difficult, respectively, to do work, take care of things at home, or get along with other people; the proportion was higher in mothers than in fathers (χ2 = 11.4, df = 3, p = 0.01). The PHQ-9 total score of parents mildly correlated with the SDQ score of children and adolescents (r =0.51, p = 0.01, Figure). Mental health problems of children/parents were not associated with residing in a red zone or knowing someone who was COVID positive or died from COVID-19.

The probability plots and scatter plots indicate normality and linearity. In multiple linear regression, a combination of parent sex (β = 0.08, p < 0.001), child’s history of developmental/psychiatric problems (β = 0.02, p = 0.67), and the SDQ total score of children and adolescents (β = 0.52, p = 0.03) accounted for 27% of the variability in depression status (PHQ total score) of parents.

Discussion

In our study, the prevalence of emotional and behavioural problems among children and adolescents was 21.5% during the lockdown, whereas in previous studies in Bangladesh, the prevalence of psychiatric disorder was 15% among 5 to 10 years old14 and 18% among all children and adolescents.10

Recently, the prevalence of predictive psychiatric disorder increased to 39.7% during the lockdown.8 Another study estimated that 43% of children had sub-threshold mental health disturbances, with 19.3% and 7.2% having moderate and severe disturbances, respectively.9

Among our children and adolescents, 19.9% had hyperactivity and 26.8% had conduct problems, consistent with the corresponding prevalence of 14.1% and 29.7% reported in another study.8 Clinging, inattention, and irritability were the most common psychological conditions among children in all age groups.4 In Italy and Spain, the most frequent symptoms were difficulty in concentrating (76.6%), boredom (52%), irritability (39%), and restlessness (38.8%). In children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, home confinement increased hyperactivity and impulsivity as well as caregiver difficulty in engaging these children in meaningful activities.15

In China, the three most common symptoms among children and adolescents were anxiety (24.9%), depression (19.7 %), and stress (15.2%).16 About 25% of young adult students experienced at least mild anxiety symptoms.17 22.6% and 18.9% of students reported depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively.18 The prevalence of depression in children was 2.22%, and 5.66% and 1.84% of children experienced mild and moderate anxiety, respectively.19 In the present study, 10.2% of children and adolescents had emotional problems, which is lower than that reported in other studies in Bangladesh: 23.4% having emotional disorder,8 15.9% and 9.2% having moderate depression and anxiety, respectively, and 7.2% having severe disturbances.9

The differences may be due to the time of data collection. Our study was conducted a month after lockdown; the other studies was conducted a few months later. Prolonged lockdown may have increased the prevalence of emotional disorder among children and adolescents. Loneliness in the COVID-19 context was associated with subsequent mental health problems (depression and anxiety) in children and adolescents.20

In the present study, 5.5% and 2.9% parents had moderately severe and severe depression, respectively. In a nationwide research between 2003 and 2005, 4.6% of adults in Bangladesh had depressive disorder.21 In a global study, the prevalence of depressive disorder in Bangladesh was 3.9% (95% confidence interval, 3.6%-4.2%).22 Thus, the prevalence of depression is higher during the pandemic. In China during the pandemic, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in parents measured by PHQ-9 was 6.1% and 4.0%, respectively,23 whereas 22.8%, 3.6%, and 0.01% of parents were mildly, moderately, and severely depressed, respectively.19

Income loss, caregiver burden, and illness were hardships experienced by families. Parents’ and children’s well-being was strongly associated with the number of hardships family experienced.24. In USA, parents who reported higher rates of caregiver burden also reported higher rates of generalised anxiety and depression, with male caregivers reporting higher rates overall than female caregivers.25 However, in our study, more mothers than fathers had depression. The difference may be because fathers play much less role in child rearing in Bangladesh. Similarly in China during the pandemic, women were at a higher risk of depression and higher levels of psychological stress than men.26 Being a mother, being younger, and having lower levels of educational attainment and family monthly income were risk factors for anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder for parents.19

One in 10 families reported worsening of both parental mental health and children’s behavioural health. This indicates that the mental health of parents and children are intertwined.5 There are significant associations among parents’ caregiver burden, mental health, and perceptions of children’s stress.25 Parents with higher levels of depression reported higher stress in their children.25 In the present study, parental depression mildly correlated with poor mental health of children and adolescents.

Greater COVID-19-related stressors and high anxiety and depressive symptoms are associated with higher parental perceived stress.27 During the pandemic, >50% of families experienced job loss and income loss; 45% experienced increased care-giving burden; and 12% had a sick family member.24 Parental anxiety and depression can be affected by perceived stress, social support, marital satisfaction, family conflicts, child’s learning stage, and parent’s history of mental problems.23 However, these factors were not taken into account in our study. Only parent’s sex, child’s history of developmental/mental problems, and child’s SDQ score were included as predictors of parental depression. The three predictors cumulatively predicted only 27% of the variability of parental depression.

Sex and age were predictors of the psychological status of parents but not for children.19 Compared with families with older children, families with younger children reported a higher proportion of worsening mental and behavioural health.5 However, we found no association between parent mental health and age of children/parent.

One limitation of our study is online data collection. The requirement of internet connection may result in selection bias, as participants were mostly from urban area with higher levels of socioeconomic status, although >102 million people in Bangladesh (62% of Bangladeshi population) has internet access.28 In addition, the sample may not be representative of the whole country.

Conclusion

During lockdown, the increased prevalence of psychiatric disorder among children and adolescents and their parents necessitates immediate and long-term management strategies. We recommend opening the schools as soon as the situation improves and developing interventions such as virtual mental health assessment for children and adolescents and their parents.

Contributors

SES and NMK designed the study. NMK and HUA acquired the data. SES analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. HUA critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Mental Health, Bangladesh (reference: NIMH/2020/253).

References

- Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:421. Crossref

- Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2020;14:20. Crossref

- Ma H, Hu J, Tian J, et al. A single-center, retrospective study of COVID-19 features in children: a descriptive investigation. BMC Med 2020;18:123. Crossref

- Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr 2020;221:264-6. e1. Crossref

- Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics 2020;146:e2020016824. Crossref

- Marques de Miranda D, da Silva Athanasio B, Sena Oliveira AC, Simoes-E-Silva AC. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 2020;51:101845. Crossref

- Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:36-8. Crossref

- Mallik CI, Radwan RB. Impact of lockdown due to COVID-19 pandemic in changes of prevalence of predictive psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents in Bangladesh. Asian J Psychiatr 2021;56:102554. Crossref

- Yeasmin S, Banik R, Hossain S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020;117:105277. Crossref

- Rabbani MG, Alam MF, Ahmed HU, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders, mental retardation, epilepsy and substance abuse in children. Bangladesh J Psychiatry 2009;23:11-53.

- Mullick MS, Goodman R. Questionnaire screening for mental health problems in Bangladeshi children: a preliminary study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001;36:94–9. Crossref

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606-13. Crossref

- Chowdhury AN, Ghosh S, Sanyal D. Bengali adaptation of brief patient health questionnaire for screening depression at primary care. J Indian Med Assoc 2004;102:544-7.

- Mullick MS, Goodman R. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among 5-10 year olds in rural, urban and slum areas in Bangladesh: an exploratory study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:663-71. Crossref

- Cortese S, Asherson P, Sonuga-Barke E, et al. ADHD management during the COVID-19 pandemic: guidance from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4:412-4Crossref

- Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord 2021;279:353-60. Crossref

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 2020;287:112934. Crossref

- Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei province, China. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174:898-900. Crossref

- Yue J, Zang X, Le Y, An Y. Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Curr Psychol 2020:1-8. Crossref

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020;59:1218-39.e3. Crossref

- Firoz AHM, Karim ME, Alam MF, Rahman AHMM, Zaman MM. Prevalence, medical care, awareness and attitude towards mental illness in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Psychiatry 2006;20:9-36.

- Ogbo FA, Mathsyaraja S, Koti RK, Perz J, Page A. The burden of depressive disorders in South Asia, 1990-2016: findings from the global burden of disease study. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:333. Crossref

- Wu M, Xu W, Yao Y, et al. Mental health status of students’ parents during COVID-19 pandemic and its influence factors. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33:e100250. Crossref

- Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Fitz-Henley J 2nd. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics 2020;146:e2020007294. Crossref

- Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent-child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2020;51:671-82. Crossref

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:1729. Crossref

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl 2020;110:104699. Crossref

- Internet Subscribers in Bangladesh in May 2020. Available from: http://www.btrc.gov.bd/content/internet-subscribers-bangladesh- may-2020 Accessed 7 February 2022.