East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2021;31:81-3 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap2040

CASE REPORT

SS Nair, CJM Chua, DCL Teo

Sanjiv Sasidharan Nair, Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Chester JieMin Chua, MOH Holdings, Singapore

David Choon Liang Teo, Department of Psychological Medicine, ChangiGeneral Hospital, Singapore

Address for correspondence: David Choon Liang Teo, Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, 2 Simei Street 3, Singapore 529889.

Email: david.teo.c.l@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 4 June 2021

Abstract

Lurasidone is used for treatment of bipolar depression in adults and adolescents. Lurasidone-associated manic switch has been reported in adults but not yet in adolescents. We report a case of lurasidone-induced manic switch in a male adolescent treated for bipolar I depression. Five days after adding lurasidone to his regimen (sodium valproate and olanzapine), our patient became manic with psychotic features. After discontinuation of lurasidone, he was stabilised with electroconvulsive therapy, and the medication was switched to a lithium-quetiapine combination. This case highlights the potential risk of lurasidone- induced manic switch in adolescents with bipolar depression.

Key words: Adolescent; Bipolar disorder; Depression; Lurasidone hydrochloride; Mania

Introduction

Bipolar depression is challenging to treat owing to limited effective psychopharmacological options and the need to rapidly alleviate depression while avoiding precipitating mania or hypomania and decreasing cycling time. Lurasidone is approved for treatment of bipolar depression in both adults and adolescents. It is increasingly popular owing to strong efficacy and favourable adverse-effect profile. Although treatment-emergent mania associated with lurasidone has been reported in adults, there is no such report in adolescents. We report a case of treatment- emergent mania after the use of lurasidone for bipolar I depression in a male adolescent.

Case presentation

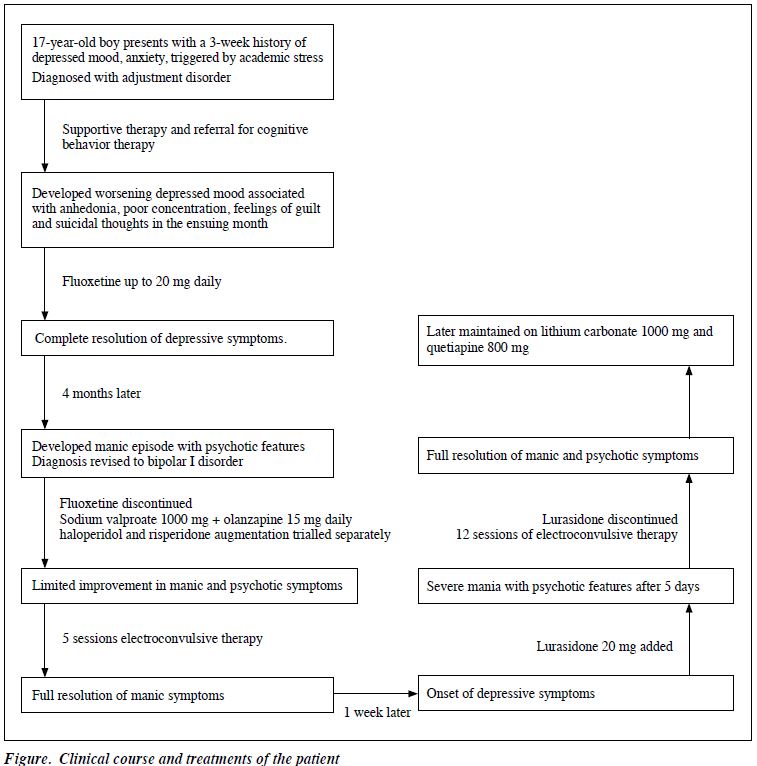

In April 2017, a 17-year-old Chinese male presented to the psychiatric service of a general hospital in Singapore with low mood and anxiety precipitated by scholastic stressors. The clinical course and treatments are summarised in the Figure. He was initially diagnosed with adjustment disorder and treated with psychotherapy. One month later, his diagnosis was revised to major depressive disorder after he became increasingly depressed, along with anhedonia, anergia, poor concentration, feelings of guilt, and suicidal thoughts. At this juncture, he was commenced on fluoxetine 20 mg daily and experienced full remission of symptoms. Four months later, while on fluoxetine 20 mg daily, he presented with a manic episode characterised by elated mood, racing thoughts, increased energy, poor sleep, hypersexual behaviour, and grandiose delusions. Routine laboratory test results for thyroid function and toxicology were unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no abnormality. His diagnosis was revised to bipolar I disorder.

Fluoxetine was promptly discontinued. Sodium valproate and olanzapine were started concurrently, and sedatives lorazepam and diazepam were prescribed as needed. However, the patient showed limited initial response to olanzapine (up to 15 mg) and sodium valproate (up to 1000 mg). A trial of haloperidol and risperidone was separately added, but neither yielded additional benefit as combination therapy. The patient later underwent five sessions of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and achieved full resolution of manic symptoms. He was maintained on sodium valproate 1000 mg and olanzapine 10 mg daily.

One week after resolution of the manic episode, the patient became depressed again. He was started on lurasidone 10 mg, then 20 mg 3 days later. Five days after commencing lurasidone, he developed a severe episode of mania with psychotic features, despite remaining on sodium valproate and olanzapine. Lurasidone was discontinued on suspicion of a lurasidone-induced manic switch. He subsequently underwent 12 sessions of ECT for stabilisation, and his medications were switched to a lithium-quetiapine combination. Following the manic episode, he has been maintained well outpatient on quetiapine 800 mg and lithium carbonate 1000 mg daily.

Discussion

In our patient, lurasidone-induced manic switch was suspected, because manic symptoms manifested very shortly after commencing lurasidone. The patient was euthymic for a week with complete resolution of his previous manic symptoms before his mood declined. This makes it less likely that the emergent manic symptoms were due to a partially treated manic state from the first course of ECT. In addition, the patient developed severe manic symptoms despite being on two other mood stabilising medications (sodium valproate and olanzapine).

Drug-induced mania is thought to result from an elevation of norepinephrine or dopamine levels via blockade at their reuptake site, even during mood-stabilising co- treatment.1 Lurasidone has high-affinity antagonism for D2, 5HT2A, and 5HT7 receptors, and moderate affinity for 5HT1A and α2c receptors.2 Lurasidone’s antidepressant property has been attributed to its 5HT1A partial agonism and 5HT7 antagonism.2 However, these mechanisms also give rise to cortical dopaminergic efflux,3 which may increase the risk of treatment-emergent mania. Lurasidone’s potent 5HT7 antagonism generated interest for its possible pro-cognitive effects, as cognitive deficits in schizophrenia have been linked to hypofunction of prefrontal dopaminergic and glutaminergic neurons.2 When used in patients with bipolar depression, the elevation of dopamine levels may precipitate a manic switch.

The pharmacokinetic profile of lurasidone in adolescents shows similar dose-proportional exposure levels as in adults.2 However, psychotropic adverse effects may vary idiosyncratically with pharmacogenetic profile. For example, those with deficiency of the CYP2D6 enzyme are poor metabolizers (although less prevalent in the Asian populations) who have higher rates of antidepressant- induced manic switch, particularly with fluoxetine and paroxetine.4

There are potential confounders in our case. First, both olanzapine and lurasidone have been associated with treatment-emergent mania. Both disinhibit frontal dopamine release; the combined effect may have increased the likelihood of manic switch, despite being on sodium valproate. Second, a manic episode may be expected to shortly follow a depressive phase of a rapid cycling illness. It is plausible that the mania arose was part of the natural course of illness. In a randomised controlled study in adolescents with bipolar depression, the rate of ‘treatment- emergent mania’ is similar between lurasidone and placebo arms.5 Third, the initial course of ECT may have been insufficient, and the first manic episode was only partially treated. However, this is less likely as our patient remained euthymic for a week in the inpatient unit before developing depressive symptoms that prompted the addition of lurasidone.

The US Food and Drug Administration recommends either lurasidone or olanzapine-fluoxetine combination for treating bipolar I depression in young persons aged 10 to 17 years. Lurasidone is also recommended as a first-line treatment for bipolar depression by both the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments and International Society for Bipolar Disorders. Nonetheless, the most robust safety data are pooled from studies on adults from predominantly Caucasian populations. Our case of possible lurasidone-induced manic switch in an adolescent with bipolar depression underscores the need for clinicians to be vigilant. Further studies on lurasidone use in adolescents with bipolar I disorder, particularly in Asian populations, are needed to determine age- or population- specific variation in treatment-emergent mania.

Contributors

All authors designed the study, acquired the data, analysed the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to the data, contributed to the study, approved the final version for publication, and take responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Funding/support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The patients were treated in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent for all treatments and procedures.

References

- Young JW, Dulcis D. Investigating the mechanism(s) underlying switching between states in bipolar disorder. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;759:151-62. Crossref

- Greenberg WM, Citrome L. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lurasidone hydrochloride, a second-generation antipsychotic: a systematic review of the published literature. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017;56:493-503. Crossref

- Huang M, Horiguchi M, Felix AR, Meltzer HY. 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors contribute to lurasidone-induced dopamine efflux. Neuroreport 2012;23:436-40. Crossref

- Sánchez-Martín A, Sánchez-Iglesias S, García-Berrocal B, Lorenzo C, Gaedigk A, Isidoro-García M. Pharmacogenetics to prevent maniac affective switching with treatment for bipolar disorder: CYP2D6. Pharmacogenomics 2016;17:1291-3. Crossref

- DelBello MP, Goldman R, Phillips D, Deng L, Cucchiaro J, Loebel A. Efficacy and safety of lurasidone in children and adolescents with bipolar I depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:1015-25. Crossref