East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2019;29:118-23 | https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1851

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Prevalence

Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, MD, DrPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Hazli Zakaria, MBBS, DrPsych, Department of Psychiatry, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Address for correspondence: Dr Luke Sy-Cherng Woon, Department of Psychiatry, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Email: lukewoon@gmail.com

Submitted: 18 May 2018; Accepted: 12 October 2018

Abstract

Objective: To determine the prevalence of adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and comorbid mental disorders in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital.

Methods: All adult patients admitted to the forensic wards who were able to understand Malay or English language and give written informed consent were included. Participants were assessed using the Conners Adult Attention-Deficit Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (for presence of adult ADHD and a history of childhood ADHD) and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (for psychiatric comorbidities). Sociodemographic and offence-related data were also collected.

Results: Of 199 patients admitted, 120 were included for analysis. The mean age of participants was 36.3 years. 94.2% were men. 81.7% were single, divorced, or separated. 25% had a history of childhood ADHD. The prevalence of adult ADHD was 15.8%. The persistence rate was 63%. Among the 19 participants with adult ADHD, the most common psychiatric comorbidities were substance dependence (68.4%), lifetime depression (63.2%), and generalised anxiety disorder (47.4%). Compared with participants without ADHD, participants with adult ADHD were less likely to be married (0% vs 21.8%, p = 0.022) and more likely to have alcohol abuse (15.8% vs 2%, p = 0.028), lifetime manic/hypomanic episodes (42.1% vs 7.9%, p = 0.001), and generalised anxiety disorder (47.4% vs 19.8%, p = 0.017), and were of younger age at first offence (21.8 years vs 26.9 years, p = 0.021).

Conclusions: Adult ADHD is common in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital and is associated with unmarried status, alcohol abuse, lifetime manic/hypomanic episodes, generalised anxiety disorder, and younger age at first offence.

Key words: Attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity; Comorbidity; Forensic psychiatry; Hospitals, psychiatric;

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterised by high levels of hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention since early childhood. The prevalence of childhood ADHD is estimated to be 4.0% to 8.0%.1 In 15% of cases, the condition persists to age 25 years, and further 50% of cases were in partial remission.2 The pooled prevalence of adult ADHD in meta-analyses has been 2.5% to 5.0%.3,4

Childhood predictors of adult ADHD include treatment for ADHD and combined subtype of childhood ADHD, symptom severity, comorbidity with conduct and mood and anxiety disorders, psychosocial adversity, parental psychopathology, and family history of ADHD.5,6 Other risk factors are male sex, low educational level, unemployment, and unmarried status.7,8

The lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders is significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in the general population.9 80% of adult ADHD cases have comorbidities.10 Adult ADHD is associated with 5.4 times increased risk of bipolar disorder,7 and 65% of adults with ADHD have major depression.9 Adults with ADHD have 7.5 times higher odds of having any anxiety disorders and 3.8 times higher odds for all types of substance use disorder.7

The prevalence of ADHD is 33% to 65% among individuals with cluster B personality disorders, and comorbidity of ADHD and antisocial personality disorder is common in the forensic population.11

In two meta-analyses, the prevalence of ADHD in prison populations was estimated to be 25.5% and 26.2%.12,13 In the Forensic Mental Health Services of the United Kingdom, 33% of patients with personality disorders were positive for ADHD.14 Prisoners with ADHD involve in more aggressive incidents and have significantly younger onset of offending and higher rate of recidivism.15

To the best of our knowledge, no study on adult ADHD in forensic mental hospitals has been carried out in Malaysia. This study aimed to determine in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital (1) the prevalence of adult ADHD, (2) the prevalence of comorbid alcohol and substance use disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, and antisocial personality disorder, (3) the age of first offence and types of current offence, and (4) the rate of aggressive incidents in ward.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committees of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2016-399) and the Ministry of Health Malaysia (KKM/NIHSEC/P16-1059). This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Hospital Bahagia Ulu Kinta from June 2017 to November 2017. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Using the formula with finite population correction, the sample size for prevalence studies was calculated to be 113.16 The projected number of patients over 6 months was 180 based on the median of 30 admissions per month. Given an estimated recruitment rate of 65%, the expected sample size was 117.

All patients admitted to the forensic wards (including those admitted under court order for assessment and those transferred from prisons for treatment) were included. Inclusion criteria were age 18 to 65 years, ability to understand Malay or English language, and ability to give written informed consent. The latter was based on the ability to understand, retain, and weigh the relevant information to make and communicate the decision. Patients were excluded if they were non-Malaysian citizens, unable to cooperate in the interview (owing to active psychosis, dementia, severe learning disability, or any medical conditions that substantially affect cognitive function), or unwilling to participate.

Patients were interviewed by the first author. The structured interview took 1 to 2.5 hours to complete and was divided into sessions to reduce participant discomfort and response bias secondary to prolonged interviews.

The Conners Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID) was used to assess the presence of adult ADHD and a history of childhood ADHD. The CAADID is a clinician-administered structured interview for diagnosis of ADHD during both adulthood and childhood based on DSM-IV criteria.17 It has good test-retest reliability for adult ADHD (κ = 0.67) and childhood ADHD (κ = 0.69) as well as good concurrent validity.18

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) was used to assess other psychiatric comorbidities, including alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, substance abuse, substance dependence, lifetime depressive episode, lifetime manic/hypomanic episode, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, diagnostic interview compatible with the DSM-IV.19 The interview takes 15 to 30 minutes with trained professionals. The English and Malay versions have been validated for clinical use. The Malay version has satisfactory inter-rater reliability (0.67 to 0.85) and good concordance with expert diagnoses (κ > 0.88).20

Sociodemographic variables were collected, including age, sex, marital status, educational level, occupation, and homelessness. Criminality data were collected, including age of first convicted offence and type of offence (violent or non-violent) for the current admission. Violent offences included murder and attempted murder, gang robbery with or without firearm, robbery with or without firearm, rape, and voluntarily causing grievous hurt.21 Non-violent offences included all remaining property, drug, and public order offences. The number of aggressive incidents in the ward (physical aggression, verbal aggression, damage to property, and self-injurious behaviour) was also recorded.

Data were analysed using SPSS (Windows version 20; IBM Corp, Armonk [NY], US). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality of continuous variables. Log transformation of age and age of onset of offence showed normal distribution. The ADHD and non-ADHD groups were compared using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and independent t test or Mann- Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05.

Results

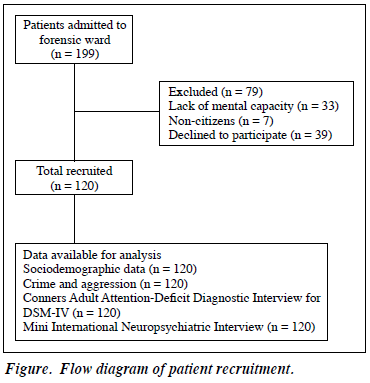

Of 199 patients admitted, 79 were excluded and 120 were included for analysis (Figure). The mean age of participants was 36.3 ± 9.86 years. 94.2% were men. 18.3% were married and 81.7% were single, divorced, or separated.

85.9% had secondary or above educational level. 70.8% were employed, mostly in unskilled jobs (n = 23, 19.2%). 16 participants were homeless during the past 6 months (Table 1).

Of the participants, 25% had a history of childhood ADHD in terms of inattentive subtype (9.2%), hyperactive/ impulsive subtype (4.2%), and combined subtype (11.7%). The prevalence of adult ADHD was 15.8% in terms of inattentive subtype (7.5%), hyperactive/impulsive subtype (4.2%), and combined subtype (4.2%). The persistence rate was 63%. Only three adult ADHD patients were previously diagnosed; none was on treatment.

Of the participants, 15.8% had alcohol dependence and 52.5% had substance dependence, with amphetamine- type stimulants being most common (45.8%), followed by opioids (30.0%) and cannabis (18.3%). 30% had current or recurrent major depression, and 15% had a past history of major depressive episode. 1.6% had current mania or hypomania. 24.2% had generalised anxiety disorder. 28.3% had antisocial personality disorder.

Among the participants, the mean age of first convicted offence was 26.1 ± 9.03 years. 50.8% were admitted for violent offences. 20 participants committed 45 aggressive incidents in the ward including physical aggression (n = 24), verbal aggression (n = 19), and self-injury (n = 2). No damage to property occurred.

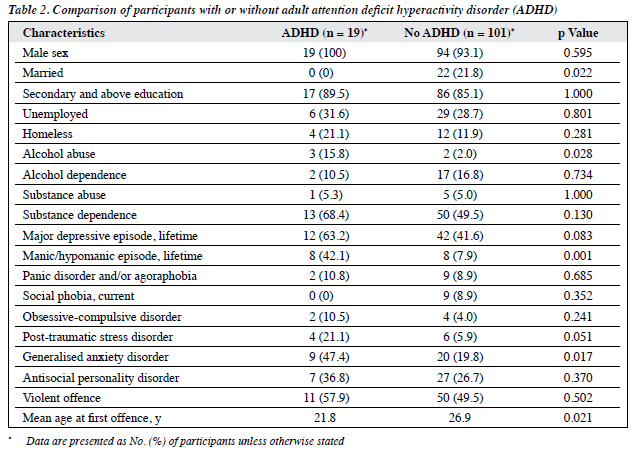

Compared with participants without ADHD, participants with adult ADHD were less likely to be married (0% vs 21.8%, p = 0.022) and more likely to have alcohol abuse (15.8% vs 2%, p = 0.028), lifetime manic/hypomanic episodes (42.1% vs 7.9%, p = 0.001), and generalised anxiety disorder (47.4% vs 19.8%, p = 0.017), and were of younger age at first offence (21.8 years vs 26.9 years, p = 0.021) [Table 2].

Compared with inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive subtypes, combined subtype had higher persistence rate of ADHD diagnosis into adulthood (92.9% vs 37.5%, p = 0.002).

Discussion

The prevalence of adult ADHD among forensic patients in a Malaysian mental hospital is 15.8%, consistent with 16.2% in Iranian male prisoners22 and 11% in France male prisoners.23 Only three participants were previously diagnosed with adult ADHD; this indicates underdiagnosis of the condition. Clinicians have inadequate understanding of adult ADHD and thus hesitate to make the diagnosis.24 In addition, approved pharmacotherapy for adult ADHD is not available in Malaysia. Adequate training, availability of easy-to-administer screening tools (such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale25), and effective treatments may improve recognition and treatment of adult ADHD.

All seven female participants did not have adult ADHD, but the sample was too small to conclude that adult ADHD is rare among female forensic patients. In general population, adult ADHD is less common in females, with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1.3 However, among female prisoners in Britain, 41% met ADHD diagnosis in both childhood and adulthood.26

The ADHD persistence rate of 63% was within the range of 5% to 75% reported in one study.27 Participants with combined subtype of childhood ADHD had higher persistence rate than those with other subtypes. Combined childhood ADHD is a risk factor for persistence of ADHD,5 as is the unmarried status.8 Maintaining long-term relationships in the presence of persistent ADHD symptoms is challenging, and the lack of stable relationships in turn increases stress and worsens overall functioning.

A meta-analysis reported that incarcerated adults with ADHD have higher risks for mood and anxiety disorders, with odds ratio ranging from 1.82 to 2.96.28 Participants with adult ADHD were more likely to have lifetime manic/ hypomanic episodes than those with no ADHD. ADHD and bipolar disorder share common features such as impulsivity and increased energy and distractibility. Indeed, emotional impulsivity and deficient emotional self-regulation are considered central features of ADHD29 and manifest similarly to bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is not only a differential diagnosis of ADHD, but can also coexist with ADHD in up to 20% of adult ADHD patients.30 Both conditions have strong familial links, and neuroimaging studies have implicated similar brain regions, namely frontal region and basal ganglia.31

Anxiety in adult ADHD is associated with more global impairment, poorer outcome, and greater treatment costs.32 In children, ADHD is more prevalent in patients with generalised anxiety disorder than in those with other anxiety disorders such as social phobia.33 Anxiety symptoms may be closely related to the pathogenesis of ADHD, as executive functioning deficits in ADHD (problem-solving difficulties and poor emotional self-regulation) may cause the anxiety symptoms in generalised anxiety disorder.34

Adults with comorbid ADHD and substance use disorder have earlier onset and more severity of substance use than those without ADHD.11 However, participants with adult ADHD was associated with alcohol abuse only but not substance abuse or dependence. This is probably due to the high base rate of substance dependence in the sample, in which many were arrested for drug-related offences. According to the Ministry of Home Affairs of Malaysia in 2017, the number of imprisonments for drug-related offences was two times more than that for other criminal offences (72 384 vs 35 955).35

Hyperactivity-impulsivity may predict increased criminal offending among individuals with persistent ADHD in early adulthood.36 Adults with ADHD had a younger age of onset of offending by around 2.5 years than those without ADHD (16 years vs 19.5 years).15 The impact of untreated ADHD symptoms, especially in early adulthood, on criminal involvement should not be underestimated. In participants with adult ADHD, higher rates (though not significantly) of aggressive incidents, antisocial personality disorder, and violent offence might also reflect the higher level of offender behaviours.15

Although the sample size was adequate to estimate adult ADHD prevalence in the study population, there is limited statistical power to detect between-group differences for a number of variables. History about childhood ADHD symptoms was based on participant recall only, without collaborative history from parents or other relatives. Recall bias is recognised in a longitudinal study of ADHD,37 and thus the prevalence of childhood ADHD may have been underestimated. In addition, cross-sectional studies cannot establish temporal or causal association between adult ADHD and other factors.

Conclusion

Adult ADHD is common in a Malaysian forensic mental hospital and is associated with unmarried status, alcohol abuse, lifetime manic/hypomanic episodes, generalised anxiety disorder, and younger age at first offence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Norhayati Nordin, Dr Rabaiah Mohd Salleh, Dr Suarn Singh, Dr Ong Lieh Yan, Ms Tunku Saraa Zawyah Tunku Badli, Dr Fairuz Nazri Abdul Rahman, and Dr Nazarudin Safian for their support and advice. This work was supported by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre Fundamental Fund (FF-2016-332).

Declaration

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry 2003;2:104-13.

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 2006;36:159-65. Crossref

- Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, Mészáros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta- analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:204-11. Crossref

- Willcutt EG. The prevalence of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Neurotherapeutics 2012;9:490-9Crossref

- Lara C, Fayyad J, de Graaf R, Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Angermeyer M, et al. Childhood predictors of adult attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Biol Psychiatry 2009;65:46-54Crossref

- Caye A, Spadini AV, Karam RG, Grevet EH, Rovaris DL, Bau CH, et al. Predictors of persistence of ADHD into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;25:1151-9. Crossref

- Fayyad J, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Adamowski T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2017;9:47-65. Crossref

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:716-23. Crossref

- Rucklidge JJ, Downs-Woolley M, Taylor M, Brown JA, Harrow SE. Psychiatric comorbidities in a New Zealand sample of adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2016;20:1030-8. Crossref

- Yoshimasu K, Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Weaver AL, et al. Adults with persistent ADHD: gender and psychiatric comorbidities: a population-based longitudinal study. J Atten Disord 2018;22:535-46. Crossref

- Kooij JJS. Adult ADHD: Diagnostic Assessment and Treatment, 3rd London: Springer-Verlag; 2013. Crossref

- Young S, Moss D, Sedgwick O, Fridman M, Hodgkins P. A meta- analysis of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in incarcerated populations. Psychol Med 2015;45:247-58. Crossref

- Baggio S, Fructuoso A, Guimaraes M, Fois E, Golay D, Heller P, et al. Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in detention settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:331. Crossref

- Young S, Gudjonsson G, Ball S, Lam J. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in personality disordered offenders and the association with disruptive behavioural problems. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol 2003;14:491-505. Crossref

- Young S, Wells J, Gudjonsson GH. Predictors of offending among prisoners: the role of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance use. J Psychopharmacol 2011;25:1524-32. Crossref

- Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci 2006;1:9-14.

- Epstein J, Johnson DE, Conners CK. Conners’Adult ADHD Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV (CAADID). New York: Multi-Health Systems; 2001.

- Epstein JN, Kollins SH. Psychometric properties of an adult ADHD diagnostic interview. J Atten Disord 2006;9:504-14. Crossref

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998:59(Suppl 20):22-33.

- Mukhtar F, Abu Bakar AK, Mat Junus MM, Awaludin A, Abdul Aziz S, Midin M, et al. A preliminary study on the specificity and sensitivity values and inter-rater reliability of Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) in Malaysia. ASEAN J Psychiatry 2012;13:157-64.

- Muhammad Amin B, Mohammad Rahim K, Geshina Ayu MS. A trend analysis of violent crimes in Malaysia. Health Environ J 2014;5:41-56.

- Hamzeloo M, Mashhadi A, Salehi Fadardi J. The prevalence of ADHD and comorbid disorders in Iranian adult male prison inmates. J Atten Disord 2016;20:590-8. Crossref

- Gaïffas A, Galéra C, Mandon V, Bouvard MP. Attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in young French male prisoners. J Forensic Sci 2014;59:1016-9. Crossref

- Quintero J, Balanzá-Martínez V, Correas J, Soler B; Grupo Geda-A. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the adult patients: view of the clinician. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2013;41:185-95.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Ames M, Demler O, Faraone S, Hiripi E, et al. The World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): a short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol Med 2005;35:245-56. Crossref

- Farooq R, Emerson LM, Keoghan S, Adamou M. Prevalence of adult ADHD in an all-female prison unit. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2016;8:113-9. Crossref

- Sibley MH, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Hechtman LT, Owens EB, Stehli A, et al. Defining ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood: optimizing sensitivity and specificity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017;58:655-62. Crossref

- Young S, Sedgwick O, Fridman M, Gudjonsson G, Hodgkins P, Lantigua M, et al. Co-morbid psychiatric disorders among incarcerated ADHD populations: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2015;45:2499-510 Crossref

- Barkley RA. Emotional dysregulation is a core component of ADHD. In: Barkley RA, editor. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: a Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2015:81-115.

- Brus MJ, Solanto MV, Goldberg JF. Adult ADHD vs. bipolar disorder in the DSM-5 era: a challenging differentiation for clinicians. J Psychiatr Pract 2014;20:428-37. Crossref

- Klassen LJ, Katzman MA, Chokka P. Adult ADHD and its comorbidities, with a focus on bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2010;124:1-8. Crossref

- Van Ameringen M, Patterson B, Simpson W, Turna J, Pullia K. Adult ADHD with anxiety disorder and depression comorbidity in a clinical trial cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016;41:S486-7.

- Safren SA, Lanka GD, Otto MW, Pollack MH. Prevalence of childhood ADHD among patients with generalized anxiety disorder and a comparison condition, social phobia. Depress Anxiety 2001;13:190-1. Crossref

- Jarrett MA. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and executive functioning in emerging adults. Psychol Assess 2016;28:245-50. Crossref

- Ministry of Home Affairs, Malaysia. Statistik Kemasukan Banduan di bawah Kesalahan Syariah, Dadah, Imigresen dan Jenayah pada Tahun 2013 hingga 2017. Available from: http://www.data.gov.my/data/ en_US/dataset/statistik-kemasukan-banduan-di-bawah-kesalahan- syariah-dadah-imigresen-dan-jenayah/resource/2afe782c-0302-4541- 9096-4d312b2166b1. Accessed 21 August 2018.

- Philipp-Wiegmann F, Rösler M, Clasen O, Zinnow T, Retz-Junginger P, Retz W. ADHD modulates the course of delinquency: a 15-year follow-up study of young incarcerated man. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2018;268:391-9. Crossref

- Miller CJ, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Fading memories: retrospective recall inaccuracies in ADHD. J Atten Disord 2010;14:7-14. Crossref